Published online Jul 5, 2022. doi: 10.4292/wjgpt.v13.i4.57

Peer-review started: January 28, 2022

First decision: March 10, 2022

Revised: April 27, 2022

Accepted: May 28, 2022

Article in press: May 28, 2022

Published online: July 5, 2022

Processing time: 153 Days and 7.8 Hours

Low bone mineral density (BMD) is common in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. However, nutritional risk factors for low BMD in the ulcerative colitis (UC) population are still poorly understood.

To investigate the association of anthropometric indicators and body composition with BMD in patients with UC.

This is a cross-sectional study on adult UC patients of both genders who were followed on an outpatient basis. A control group consisting of healthy volunteers, family members, and close people was also included. The nutritional indicators evaluated were body mass index (BMI), total body mass (TBM), waist circumference (WC), body fat in kg (BFkg), body fat in percentage (BF%), trunk BF (TBF), and also lean mass. Body composition and BMD assessments were performed by dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry.

The sociodemographic characteristics of patients with UC (n = 68) were similar to those of healthy volunteers (n = 66) (P > 0.05). Most patients (97.0%) were in remission of the disease, 58.8% were eutrophic, 33.8% were overweight, 39.0% had high WC, and 67.6% had excess BF%. However, mean BMI, WC, BFkg, and TBF of UC patients were lower when compared to those of the control group (P < 0.05). Reduced BMD was present in 41.2% of patients with UC (38.2% with osteopenia and 2.9% with osteoporosis) and 3.0% in the control group (P < 0.001). UC patients with low BMD had lower BMI, TBM, and BFkg values than those with normal BMD (P < 0.05). Male patients were more likely to have low BMD (prevalence ratio [PR] = 1.86; 95% confidence interval [CI]: 1.07-3.26). Those with excess weight (PR = 0.43; 95%CI: 0.19-0.97) and high WC (PR = 0.44; 95%CI: 0.21-0.94) were less likely to have low BMD.

Patients with UC in remission have a high prevalence of metabolic bone diseases. Body fat appears to protect against the development of low BMD in these patients.

Core Tip: There is a high prevalence of osteopenia/osteoporosis in adult outpatients with ulcerative colitis in remission. Patients with ulcerative colitis had a 22.4 times greater chance of developing reduced bone mineral density than healthy individuals. Lower values of body mass index and body fat indicators were identified in patients with ulcerative colitis with low bone mineral density. Low bone mineral density was associated with males and those without excess weight and with normal waist circumference.

- Citation: Lopes MB, Lyra AC, Rocha R, Coqueiro FG, Lima CA, de Oliveira CC, Santana GO. Overweight and abdominal fat are associated with normal bone mineral density in patients with ulcerative colitis. World J Gastrointest Pharmacol Ther 2022; 13(4): 57-66

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2150-5349/full/v13/i4/57.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4292/wjgpt.v13.i4.57

Low bone mineral density (BMD) is often seen in patients with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD)[1,2]. Patients with Crohn's disease and ulcerative colitis (UC), the main types of IBD, are at increased risk of fracture compared to healthy controls, with an osteoporotic fracture risk around 32%[3-6]. In patients with UC, the prevalence of osteoporosis varies between 2% to 9%[7].

The cause of osteoporosis in patients with IBD is multifactorial. Most studies involving patients with UC demonstrate that the main risk factors for this disease are related to genetics, chronic inflammatory status, treatment with steroids, and low weight[8-10].

Nutritional status appears to influence the BMD of patients with IBD. The inflammatory process and complications of the disease in the active phase can lead to compromised nutritional status, with reduced body mass and muscle mass reserves and micronutrient deficiency, and consequently to low BMD and increased risk of osteoporotic fractures[11,12]. Although the increased prevalence of over

Studies that demonstrate the relationship between nutritional risk factors and low BMD are more frequent among patients with CD considering the extension and severity of the disease, which can compromise the main sites of nutrient absorption. Thus, there is little evidence that brings the relationship of nutritional risk factors with the development of reduced BMD in patients with UC. The aim of the present study was to investigate the association of indicators of total body mass and body composition with BMD in patients with UC.

This is a cross-sectional study involving adult outpatients with UC from two reference centers. Consecutive patients with a diagnosis of UC confirmed by clinical, endoscopic, radiological, and histological criteria were included[14]. The control group consisted of healthy volunteers, family members, and close people with the same sociodemographic characteristics and lifestyle compared to the UC group. Volunteers recruited were matched for gender and age, with no history of bowel surgery or taking medications known to affect bone turnover.

Elderly people, pregnant women, patients with diseases that cause changes in bone metabolism (chronic renal failure, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, thyroid disease, liver disease, and systemic lupus erythematosus), malignant diseases, diabetes mellitus, or celiac disease, menopausal or post-menopausal patients, and those in use of estrogen therapy were not included in the study.

The clinical criteria for patients with UC were activity index and disease duration, past history of intestinal resection, accumulated dose of glucocorticoids in the last year, use of glucocorticoids for 3 mo or more, extent of disease according to Montreal classification[15], and serum calcium, albumin, and C-reactive protein (CRP) levels, in addition to smoking, regular physical activity[16], and use of calcium and vitamin D supplements.

Disease activity was assessed by the Lichtiger index[17], considering activity when a score ≥ 10 points. Calcium (mmol/L) and serum albumin (g/dL) and CRP (mg/L) were collected on the same day as the BMD evaluation and performed in the same laboratory. Calcium and albumin were measured using the dry chemical method and CRP was measured by the turbidimetry method.

Anthropometric measurements were performed by a trained and standardized team. Height (in centimeters) and body weight (in kg) were measured in duplicate, with subjects wearing light clothing and without shoes, using a scale (Filizola, São Paulo, Brazil), 150 kg capacity and 100 g interval, with an attached stadiometer with a 0.5 cm scale. The body mass index (BMI) was obtained using the formula weight/height2 and classified according to the World Health Organization[18]. For statistical analysis, two groups were considered, those with excess weight (BMI ≥ 25.0 kg/m2) and those without (BMI < 25.0 kg/m2).

Waist circumference (WC) was measured with the individual in an upright position, with feet together and without shoes. The measurement was taken with an inelastic measuring tape, which circled the individual at the midpoint between the iliac crest and the last rib[18]. High WC was considered when ≥ 80 cm for women and ≥ 90 cm for men[19].

The evaluation of body composition was performed by dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry (DXA) of the total body using a Prodigy Lunar Bone Densitometer (GE Medical Systems, United States). The equipment calibration followed the manufacturer's recommendations and both the calibration and analysis were performed by a single technician with experience in this type of assessment. The values of total body fat in percentage (BF%), total body fat in kilograms (BFkg), trunk body fat in kg (TBF), and lean mass in kilograms (LBM) were obtained. The percentage of body fat (BF%) was considered high when ≥ 25% for men and ≥ 32% for women[18].

BMD was determined by DXA in the whole body, lumbar spine (L1-L4), and femoral neck. Results of DMO are expressed in g/cm2 and also presented as T-score or Z-score. The BMD classification was based on the T-score for men 50 years of age and older and patients with UC and the Z-score for those younger than 50 years of age for men and premenopausal women. For patients with UC, the T-score was used regardless of age, considering the possibility of secondary loss of bone mass determined by the underlying disease or by the therapies used. According to the T-score, the BMD was normal up to 1 standard deviation (SD), with osteopenia values below -1 and above -2.5 SD and with osteoporosis ≤ -2.5 SD. For the Z-score, BMD ≤ -2.0 SD was considered below the estimated for the age group (BMD reduced for age). In the osteopenia/osteoporosis classification, the bone sites of the femoral neck or lumbar spine were used[20].

Results are expressed as proportions for categorical variables, the mean and SD for continuous variables with a normal distribution, and median and interquartile range for variables without a normal distribution. Mann-Whitney test was used to compare continuous variables and the chi-square test or Fisher's exact test to compare categorical variables. Poisson regression analysis with robust variance was used to obtain estimates of the prevalence ratio and the respective 95% confidence interval (CI). For all tests, a P-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. The Statistical Package for Social Science program (SPSS, Chicago, IL, United States, version 21.0) was used for data tabulation and analysis.

Informed consent was obtained from all participants and the Ethics Committee of the University Hospital Professor Edgar Santos approved the study protocol (nº117/2011).

In this study, 68 patients with UC and 66 people in the control group were included. In both groups, the majority were female and demographics, lifestyle, and use of nutritional supplements were similar (P > 0.05) (Table 1).

| Variable | UC (n = 68) | Control (n = 66) | P value |

| Age (yr), median (IR) | 39.0 (31.0-44.8) | 36.5 (29.0-43.0) | 0.484 |

| Sex (female), n (%) | 42 (61.8) | 39 (59.1) | 0.867 |

| Smoking (yes), n (%) | 2 (2.9) | 4 (6.1) | 0.437 |

| Regular physical activity (yes), n (%) | 16 (23.5) | 15 (22.7) | 1.000 |

| Duration of illness (yes), median (IR) | 5.0 (2.0-8.0) | ||

| Disease remission (yes), n (%) | 66 (97.1) | ||

| Intestinal resection history (yes), n (%) | 2 (2.9) | ||

| Extent of disease, n (%) | |||

| Proctitis | 13 (19.1) | ||

| Left colitis | 25 (36.8) | ||

| Extensive colitis | 30 (44.1) | ||

| Use of glucocorticoids (yes), n (%) | 12 (17.6) | ||

| Use ≥ 3 mo (yes), n (%) | 8 (66.7) | ||

| Accumulated dose of glucocorticoids (g), median (IR) | 1.7 (1.2-2.5) | ||

| Calcium supplement (yes), n (%) | 3 (4.4) | 0 (0) | 0.245 |

| Vit D supplement (yes), n (%) | 5 (7.4) | 0 (0) | 0.058 |

| Serum calcium (mmol/L), median (IR) | 2.3 (2.2-2.4) | 2.4 (2.3-2.4) | 0.065 |

| Serum albumin (g/dL), median (IR) | 4.3 (4.1-4.5) | 4.4 (4.1-4.6) | 0.801 |

| C-RP mg/dL, median (IR) | 1.4 (0.6-5.2) | 5.0 (1.0-6.2) | 0.004 |

| BMI (kg/m2), median (IR) | 23.7 (20.6-26.5) | 26.3 (22.8-29.0) | 0.16 |

| BMI classification, n (%) | 0.020 | ||

| Thinness | 5 (7.4) | 1 (1.5) | |

| Eutrophy | 40 (58.8) | 26 (39.4) | |

| Overweight | 16 (23.5) | 28 (42.4) | |

| Obesity | 7 (10.3) | 11 (16.7) | |

| WC (cm), median (IR) | 80.5 (72.0-89.1) | 84.6 (79.7-93.7) | 0.156 |

| LBM (kg), median (IR) | 40.1 (34.5-49.4) | 41.5 (35.3-52.2) | 0.604 |

| BF (kg), median (IR) | 17.8 (11.5-22.6) | 23.2 (17.8-28.4) | 0.001 |

| BF (%), median (IR) | 32.9 (23.7-37.6) | 34.8 (28.1-42.3) | 0.168 |

| TBF (kg), median (IR) | 8.6 (6.3-12.5) | 12.8 (7.8-16.5) | 0.354 |

| BMD (g/cm2), median (IR) | |||

| Femoral neck | 0.99 (0.90-1.07) | 1.06 (0.96-1.15) | 0.120 |

| Lumbar spine | 1.16 (1.08-1.26) | 1.21 (1.13-1.31) | 0.120 |

| Total body | 1.17 (1.11-1.24) | 1.22 (1.19-1.29 | 0.000 |

Most patients (97.0%) were in remission of the disease, only 2.9% had a previous history of intestinal resection, and extensive colitis was present in 44.1%. The use of steroids in the last year occurred in 17.6% of the patients, and of these, 66.7% used it for 3 mo or more (Table 1).

Regarding the anthropometric nutritional status, it was observed that the majority of UC patients had normal weight (58.8%); however, the frequency of overweight was high (33.8%), with six (8.8%) having grade I obesity and one (1.5%) having grade II. Women had higher BF% (37.3% vs 19.7%; P = 0.00), BFkg (22.5kg vs 12.7 kg; P = 0.00), and TBF (10.8kg vs 7.3 kg; P = 0.00) than men. BFkg and TBF of UC patients were statistically lower compared to those of the control group (P < 0.05) (Table 1).

Low BMD was present in 41.2% (n = 28) of patients with UC (38.2% with osteopenia and 2.9% with osteoporosis) and in 3.0% (n = 2) in the control group (P < 0.001). It was observed that UC patients had a 22.4 times greater chance of developing reduced BMD than healthy individuals (odds ratio = 22.4; 95%CI: 5.06 – 99.19). The majority (71.4%; 20/28) of UC patients with low BMD were younger than 45 years of age. The BMD of total body in UC patients was statistically lower compared to that of the control group (P < 0.05) (Table 1).

UC patients who had low BMD were mostly male, without regular physical activity, and had left colitis compared to those with normal BMD (P < 0.05) (Table 2). Serum calcium had a lower concentration in those with low BMD, although with a clinically irrelevant difference (Table 2). Low BMD occurred equally at both sites, the spine and femur.

| Variable | Normal BMD (n = 40) | Low BMD (n = 28) | P value |

| Age (yr), median (IR) | 37.5 (30.0-43.0) | 40.0 (32.5-46.0) | 0.193 |

| Age group, n (%) | |||

| < 45 yr | 31 (77.5) | 20 (71.4) | 0.57 |

| ≥ 45 yr | 9 (22.5) | 8 (28.6) | |

| Sex, n (%) | |||

| Male | 11 (27.5) | 15 (53.6) | 0.03 |

| Female | 29 (72.5) | 13 (46.4) | |

| Regular physical activity, n (%) | |||

| No | 27 (67.5) | 25 (89.3) | 0.04 |

| Yes | 13 (32.5) | 3 (10.7) | |

| Duration of illness (yr), median (IR) | 5.0 (2.0-9.0) | 4.5 (1.2-6.7) | 0.98 |

| Extent of disease, n (%) | |||

| Proctitis | 12 (30.0) | 1 (3.6) | 0.01 |

| Left colitis | 11 (27.5) | 14 (50.0) | |

| Extensive colitis | 17 (42.5) | 13 (46.4) | |

| Use of glucocorticoids, n (%) | |||

| No | 33 (84.6) | 22 (78.6) | 0.75 |

| Yes | 6 (15.4) | 6 (21.4) | |

| Use of glucocorticoids ≥ 3 mo, n (%) | |||

| No | 3 (50.0) | 1 (16.7) | 0.54 |

| Yes | 3 (50.0) | 5 (83.3) | |

| Accumulated dose of glucocorticoids (g), median (IR) | 1.8 (1.3-2.3) | 1.5 (1.1-3.5) | 0.55 |

| Serum calcium (mmol/L), median (IR) | 2.3 (2.3-2.4) | 2.2 (2.2-2.3) | 0.03 |

| Serum albumin (g/dL), median (IR) | 4.4 (4.1-4.6) | 4.3 (4.0-4.5) | 0.57 |

| PCR mg/dL, median (IR) | 3.1 (0.9-6.1) | 1.6 (1.6-6.3) | 0.56 |

Individuals in the control group who had low BMD (3.0%; 2/66) had osteopenia located in the lumbar spine, and all were female and without regular physical activity.

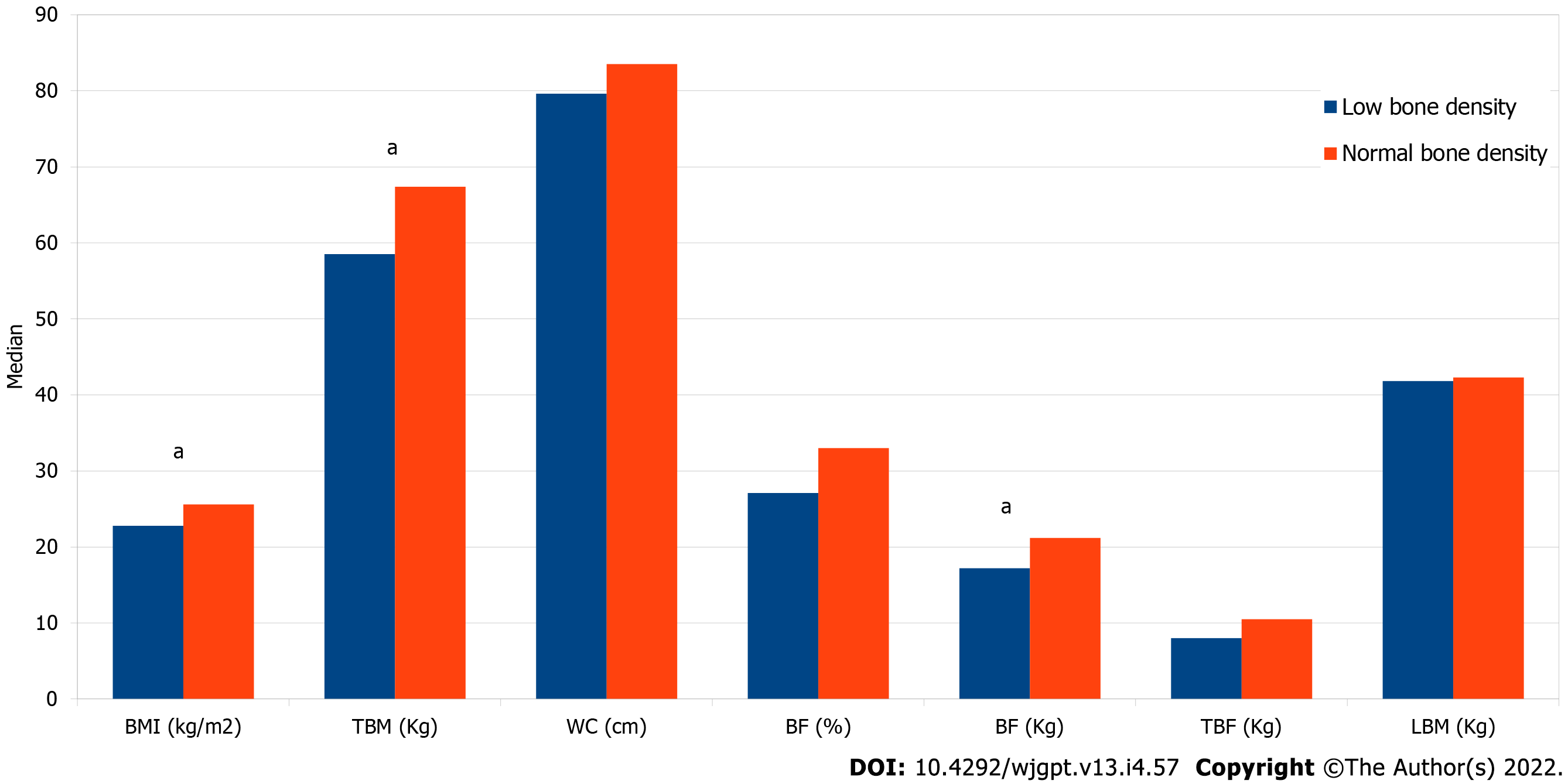

Male patients with UC were more likely to have low BMD (PR = 1.86; 95%CI: 1.07-3.26), and those with excess weight (prevalence ratio [PR] = 0.29; 95%CI: 0.13-0.66) and high WC (PR = 0.36; 95%CI = 0.17-0.75) were less likely to have low BMD (Table 3). Patients with UC with low BMD had a lower BMI value than those with normal BMD (22.8 [20.5-24.4] vs 25.6 [21.9-28.4] kg/m2; P = 0.02), TBM (58.5 [52.7-65.7] vs 67.4 [59.1-76.8] kg; P = 0.02), and BFkg (17.2 [9.9-21.3] vs 21.2 [15.4-28.4] kg; P = 0.01) (Figure 1).

| Variable | Prevalence of low BMD, n (%) | PR (95%CI) | P value | |

| Sex | ||||

| Female | 15 | 57.7 | 1.00 | |

| Male | 13 | 31.0 | 1.86 (1.07 – 3.26) | 0.029 |

| Age group | ||||

| < 45 yr | 20 | 39.2 | 1.00 | |

| ≥ 45 yr | 8 | 47.1 | 1.38 (0.46 – 4.16) | 0.583 |

| Regular physical activity | ||||

| Yes | 3 | 18.8 | 1.00 | |

| No | 25 | 48.1 | 2.56 (0.89 – 7.39) | 0.081 |

| Steroid use | ||||

| No | 23 | 38.3 | 1.00 | |

| Yes | 5 | 62.5 | 1.63 (0.87 – 3.05) | 0.126 |

| Steroid use | ||||

| < 3 mo | 1 | 25.0 | 1.00 | |

| ≥ 3 mo | 5 | 62.5 | 2.50 (0.42 – 14.8) | 0.313 |

| BMI classification | ||||

| Not overweight | 23 | 51.1 | 1.00 | |

| Overweight | 5 | 21.7 | 0.43 (0.19 – 0.97) | 0.043 |

| WC classification | ||||

| Normal | 21 | 52.5 | 1.00 | |

| Elevated | 6 | 23.1 | 0.44 (0.21 – 0.94) | 0.034 |

| BF classification (%) | ||||

| Normal | 10 | 45.5 | 1.00 | |

| Elevated | 18 | 39.1 | 0.86 (0.48 – 1.54) | 0.614 |

No significant differences were found in anthropometric nutritional characteristics or body composition between those with UC with low and normal BMD when stratified by sex.

Our data demonstrate that in a sample of patients with UC, predominantly in remission, with reduced frequency of glucocorticoid use and excess body fat, low BMD had a high prevalence, in patients under 45 years of age, being that excess weight and abdominal fat are associated with normal BMD.

It is recommended that patients with IBD be screened based on established guidelines for the general population (pre-existing fragility fracture, women aged 65 years and older and men aged 70 years and older, and those with risk factors that increase probability of detecting low bone mass)[21]. However, this is a matter of concern considering that in this sample the majority of patients with UC with reduced BMD were younger than 45 years of age, with reduced frequency of glucocorticoid use and in remission.

Bone mass loss is a frequent complication in patients with UC[22-24] and with a higher prevalence when compared to that in healthy controls[25]. Greater bone fragility increases the risk of fractures, and consequently morbidity and reduced quality of life for patients. The mechanisms reported in the literature associated with bone loss in UC patients are mainly related to the UC itself, the use of steroids, hospitalization[25-27], and low BMI values[28-31].

The role of obesity in patients with IBD is still uncertain, although initially it is believed that the greater inflammatory potential of adipose tissue could have a negative impact on the evolution of the disease in these patients[32,33]. The effect of body weight on bone mass can be attributed to the mechanical compression of weight on the skeleton, and in response, it increases bone mass to accommodate greater load[34]. In UC patients, obesity appears to be associated with a lower risk of low BMD[35], with a 5 kg/m2 increase in BMI decreasing by 57% the chance of having low BMD in 327 patients with UC and ileo-anal anastomosis with pouch illegitimate[29].

The effects of body fat on BMD in patients with IBD have been discussed[36], considering the increase in the prevalence of overweight individuals diagnosed with UC[37,38]. Although there is no clear consensus in the literature, body fat seems to have a positive effect on bone mass, as a result of the anabolic effect of mechanical tension of the fat mass on bone, in addition to the action of hormones released by adipocytes, which influence the activities of bone cells, both osteoblasts and osteoclasts[34].

The influence of gender on the BMD of patients with IBD is discordant[1,4]. In our study, male patients were more likely to have reduced BMD, which we suppose at the expense of lower body fat compared to females.

No studies were found evaluating the association between WC/abdominal fat and BMD in patients with IBD. It is known that the relationship between abdominal fat and BMD is quite complex and the results of studies in the general population are conflicting[39,40]. The two adipose tissues present in the abdominal region (subcutaneous and visceral) are highly metabolic, with the production of adipokines, estrogens, and metabolic factors derived from bones, with feedback mechanisms that affect bone remodeling and body composition[40].

Our study has some limitations. For example, serum levels of alkaline phosphatase, parathyroid hormone, and vitamin D were not measured in this study. On the other hand, it has the advantage of assessing body mass by DXA. More robust, prospective studies with larger samples and techniques for more accurate quantification of adipose tissues are needed to better explain the relationship between total and abdominal body fat and BMD.

In conclusion, we observed that male UC patients in remission have a high prevalence of metabolic bone diseases, and nutritional parameters related to body fat seem to protect against the development of low BMD. Understanding the protective effect that each nutritional component exerts on the bone mass of patients with IBD is important to assist in the development of strategies that can provide the control of metabolic bone diseases in these patients.

Inflammatory bowel disease is associated with complications such as low bone mineral density and increased risk of fracture compared to healthy controls. In patients with ulcerative colitis, the prevalence of osteoporosis varies between 2% to 9% and the main risk factors are related to genetics, chronic inflammatory status, treatment with steroids, and low weight.

There is little evidence that brings the relationship of nutritional risk factors with the development of reduced bone mineral density (BMD) in patients with ulcerative colitis, despite the studies demonstrating the relationship between nutritional risk factors and low BMD are more frequent in patients with Crohn’s disease, considering the extension and severity of factors the disease, which can compromise the main sites of nutrient absorption

To investigate the association of indicators of total body mass and body composition with BMD in patients with ulcerative colitis (UC).

This is a cross-sectional study on adult UC patients of both genders who were followed on an outpatient basis. A control group consisting of healthy volunteers, family members, and close people was also included. The nutritional indicators evaluated were body mass index (BMI), total body mass (TBM), waist circumference (WC), body fat in kg (BFkg), BF in percentage (BF%), trunk body fat (TBF), and also lean mass. Body composition and BMD assessments were performed by dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry.

Most UC patients (97.0%) were in remission of the disease, 58.8% were eutrophic, 33.8% were overweight, 39.0% had high WC, and 67.6% had excess BF%. However, mean BMI, WC, BFkg, and TBF of UC patients were lower when compared to those of the control group (P < 0.05). Reduced BMD was present in 41.2% of patients with UC (38.2% with osteopenia and 2.9% with osteoporosis) and 3.0% in the control group (P < 0.001). UC patients with low BMD had lower BMI, TBM, and BFkg values than those with normal BMD (P < 0.05). Male patients were more likely to have low BMD (prevalence ratio [PR] = 1.86; 95% confidence interval [CI]: 1.07–3.26). Those with excess weight (PR = 0.43; 95%CI: 0.19-0.97) and high WC (PR = 0.44; 95%CI = 0.21-0.94) were less likely to have low BMD.

Patients with UC in remission have a high prevalence of metabolic bone diseases and body fat appears to protect against the development of low BMD in these patients

The future perspective is to evaluate other nutritional characteristics such as food consumption.

Provenance and peer review: Invited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country/Territory of origin: Brazil

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C, C

Grade D (Fair): D, D

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Lakatos PL, Canada; Mahmoudi E, Iran; Jin X, China A-Editor: Nakaji K, Japan S-Editor: Wang LL L-Editor: Wang TQ P-Editor: Wang LL

| 1. | Even Dar R, Mazor Y, Karban A, Ish-Shalom S, Segal E. Risk Factors for Low Bone Density in Inflammatory Bowel Disease: Use of Glucocorticoids, Low Body Mass Index, and Smoking. Dig Dis. 2019;37:284-290. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Casals-Seoane F, Chaparro M, Maté J, Gisbert JP. Clinical Course of Bone Metabolism Disorders in Patients with Inflammatory Bowel Disease: A 5-Year Prospective Study. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2016;22:1929-1936. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Tsai MS, Lin CL, Tu YK, Lee PH, Kao CH. Risks and predictors of osteoporosis in patients with inflammatory bowel diseases in an Asian population: a nationwide population-based cohort study. Int J Clin Pract. 2015;69:235-241. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Bartko J, Reichardt B, Kocijan R, Klaushofer K, Zwerina J, Behanova M. Inflammatory Bowel Disease: A Nationwide Study of Hip Fracture and Mortality Risk After Hip Fracture. J Crohns Colitis. 2020;14:1256-1263. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Szafors P, Che H, Barnetche T, Morel J, Gaujoux-Viala C, Combe B, Lukas C. Risk of fracture and low bone mineral density in adults with inflammatory bowel diseases. A systematic literature review with meta-analysis. Osteoporos Int. 2018;29:2389-2397. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 50] [Cited by in RCA: 67] [Article Influence: 9.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Hidalgo DF, Boonpheng B, Phemister J, Hidalgo J, Young M. Inflammatory Bowel Disease and Risk of Osteoporotic Fractures: A Meta-Analysis. Cureus. 2019;11:e5810. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Kärnsund S, Lo B, Bendtsen F, Holm J, Burisch J. Systematic review of the prevalence and development of osteoporosis or low bone mineral density and its risk factors in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. World J Gastroenterol. 2020;26:5362-5374. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 6.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 8. | Khan ZAW, Shetty S, Pai GC, Acharya KKV, Nagaraja R. Prevalence of low bone mineral density in inflammatory bowel disease and factors associated with it. Indian J Gastroenterol. 2020;39:346-353. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Komaki Y, Komaki F, Micic D, Ido A, Sakuraba A. Risk of Fractures in Inflammatory Bowel Diseases: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2019;53:441-448. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Sgambato D, Gimigliano F, De Musis C, Moretti A, Toro G, Ferrante E, Miranda A, De Mauro D, Romano L, Iolascon G, Romano M. Bone alterations in inflammatory bowel diseases. World J Clin Cases. 2019;7:1908-1925. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 38] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 6.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Targownik LE, Bernstein CN, Leslie WD. Risk factors and management of osteoporosis in inflammatory bowel disease. Curr Opin Gastroenterol. 2014;30:168-174. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 45] [Cited by in RCA: 51] [Article Influence: 4.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Ratajczak AE, Szymczak-Tomczak A, Skrzypczak-Zielińska M, Rychter AM, Zawada A, Dobrowolska A, Krela-Kaźmierczak I. Vitamin C Deficiency and the Risk of Osteoporosis in Patients with an Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Nutrients. 2020;12. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Karaskova E, Velganova-Veghova M, Geryk M, Foltenova H, Kucerova V, Karasek D. Role of Adipose Tissue in Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Int J Mol Sci. 2021;22. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 37] [Cited by in RCA: 53] [Article Influence: 13.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 14. | Dignass A, Lindsay JO, Sturm A, Windsor A, Colombel JF, Allez M, D'Haens G, D'Hoore A, Mantzaris G, Novacek G, Oresland T, Reinisch W, Sans M, Stange E, Vermeire S, Travis S, Van Assche G. Second European evidence-based consensus on the diagnosis and management of ulcerative colitis part 2: current management. J Crohns Colitis. 2012;6:991-1030. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 728] [Cited by in RCA: 701] [Article Influence: 53.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Silverberg MS, Satsangi J, Ahmad T, Arnott ID, Bernstein CN, Brant SR, Caprilli R, Colombel JF, Gasche C, Geboes K, Jewell DP, Karban A, Loftus EV Jr, Peña AS, Riddell RH, Sachar DB, Schreiber S, Steinhart AH, Targan SR, Vermeire S, Warren BF. Toward an integrated clinical, molecular and serological classification of inflammatory bowel disease: report of a Working Party of the 2005 Montreal World Congress of Gastroenterology. Can J Gastroenterol. 2005;19 Suppl A:5A-36A. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2148] [Cited by in RCA: 2359] [Article Influence: 214.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Global Recommendations on Physical Activity for Health. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2010. [PubMed] |

| 17. | Lichtiger S, Present DH, Kornbluth A, Gelernt I, Bauer J, Galler G, Michelassi F, Hanauer S. Cyclosporine in severe ulcerative colitis refractory to steroid therapy. N Engl J Med. 1994;330:1841-1845. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1217] [Cited by in RCA: 1171] [Article Influence: 37.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Physical status: the use and interpretation of anthropometry. Report of a WHO Expert Committee. World Health Organ Tech Rep Ser. 1995;854:1-452. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Alberti KG, Zimmet P, Shaw J. Metabolic syndrome--a new world-wide definition. A Consensus Statement from the International Diabetes Federation. Diabet Med. 2006;23:469-480. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3852] [Cited by in RCA: 4225] [Article Influence: 222.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Assessment of fracture risk and its application to screening for postmenopausal osteoporosis. Report of a WHO Study Group. World Health Organ Tech Rep Ser. 1994;843:1-129. [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 21. | Farraye FA, Melmed GY, Lichtenstein GR, Kane SV. ACG Clinical Guideline: Preventive Care in Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2017;112:241-258. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 282] [Cited by in RCA: 348] [Article Influence: 43.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Ediz L, Dülger AC, Toprak M, Ceylan MF, Kemik O. The prevalence and risk factors of decreased bone mineral density in firstly diagnosed ulcerative colitis patients in the eastern region of Turkey. Int J Clin Exp Med. 2011;4:157-163. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Ismail MH, Al-Elq AH, Al-Jarodi ME, Azzam NA, Aljebreen AM, Al-Momen SA, Bseiso BF, Al-Mulhim FA, Alquorain A. Frequency of low bone mineral density in Saudi patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Saudi J Gastroenterol. 2012;18:201-207. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Ewid M, Al Mutiri N, Al Omar K, Shamsan AN, Rathore AA, Saquib N, Salaas A, Al Sarraj O, Nasri Y, Attal A, Tawfiq A, Sherif H. Updated bone mineral density status in Saudi patients with inflammatory bowel disease. World J Gastroenterol. 2020;26:5343-5353. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 25. | Lima CA, Lyra AC, Rocha R, Santana GO. Risk factors for osteoporosis in inflammatory bowel disease patients. World J Gastrointest Pathophysiol. 2015;6:210-218. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 49] [Cited by in RCA: 58] [Article Influence: 5.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 26. | Wu F, Huang Y, Hu J, Shao Z. Mendelian randomization study of inflammatory bowel disease and bone mineral density. BMC Med. 2020;18:312. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 48] [Cited by in RCA: 231] [Article Influence: 46.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Zhou T, Pan J, Lai B, Cen L, Jiang W, Yu C, Shen Z. Bone mineral density is negatively correlated with ulcerative colitis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Transl Med. 2020;9:18. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Dinca M, Fries W, Luisetto G, Peccolo F, Bottega F, Leone L, Naccarato R, Martin A. Evolution of osteopenia in inflammatory bowel disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 1999;94:1292-1297. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 87] [Cited by in RCA: 71] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Shen B, Remzi FH, Oikonomou IK, Lu H, Lashner BA, Hammel JP, Skugor M, Bennett AE, Brzezinski A, Queener E, Fazio VW. Risk factors for low bone mass in patients with ulcerative colitis following ileal pouch-anal anastomosis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2009;104:639-646. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Poturoglu S, Balkan F, Karaali ZE, Ibrisim D, Yanmaz S, Aktuglu MB, Alioglu T, Kendir M. Relationship between bone mineral density and clinical features in patients with inflammatory bowel disease: a local study in Turkish population. J Int Med Res. 2010;38:62-68. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Wada Y, Hisamatsu T, Naganuma M, Matsuoka K, Okamoto S, Inoue N, Yajima T, Kouyama K, Iwao Y, Ogata H, Hibi T, Abe T, Kanai T. Risk factors for decreased bone mineral density in inflammatory bowel disease: A cross-sectional study. Clin Nutr. 2015;34:1202-1209. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Johnson AM, Loftus EV. Obesity in inflammatory bowel disease: A review of its role in the pathogenesis, natural history, and treatment of IBD. Saudi J Gastroenterol. 2021;27:183-190. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 5.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Harper JW, Zisman TL. Interaction of obesity and inflammatory bowel disease. World J Gastroenterol. 2016;22:7868-7881. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 101] [Cited by in RCA: 114] [Article Influence: 12.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Reid IR. Relationships among body mass, its components, and bone. Bone. 2002;31:547-555. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 441] [Cited by in RCA: 426] [Article Influence: 18.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Khan N, Abbas AM, Almukhtar RM, Khan A. Prevalence and predictors of low bone mineral density in males with ulcerative colitis. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2013;98:2368-2375. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Terzoudis S, Zavos C, Koutroubakis IE. The bone and fat connection in inflammatory bowel diseases. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2014;20:2207-2217. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Flores A, Burstein E, Cipher DJ, Feagins LA. Obesity in Inflammatory Bowel Disease: A Marker of Less Severe Disease. Dig Dis Sci. 2015;60:2436-2445. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 95] [Cited by in RCA: 132] [Article Influence: 13.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (4)] |

| 38. | Bilski J, Mazur-Bialy A, Wojcik D, Surmiak M, Magierowski M, Sliwowski Z, Pajdo R, Kwiecien S, Danielak A, Ptak-Belowska A, Brzozowski T. Role of Obesity, Mesenteric Adipose Tissue, and Adipokines in Inflammatory Bowel Diseases. Biomolecules. 2019;9. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 76] [Article Influence: 12.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | Fassio A, Idolazzi L, Rossini M, Gatti D, Adami G, Giollo A, Viapiana O. The obesity paradox and osteoporosis. Eat Weight Disord. 2018;23:293-302. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 98] [Cited by in RCA: 151] [Article Influence: 21.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 40. | Gkastaris K, Goulis DG, Potoupnis M, Anastasilakis AD, Kapetanos G. Obesity, osteoporosis and bone metabolism. J Musculoskelet Neuronal Interact. 2020;20:372-381. [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] |