Published online May 15, 2017. doi: 10.4291/wjgp.v8.i2.77

Peer-review started: February 14, 2017

First decision: March 7, 2017

Revised: March 23, 2017

Accepted: April 18, 2017

Article in press: April 19, 2017

Published online: May 15, 2017

Processing time: 107 Days and 11.4 Hours

To identify factors predicting outcome of endoscopic therapy in bile duct strictures (BDS) post living donor liver transplantation (LDLT).

Patients referred with BDS post LDLT, were retrospectively studied. Patient demographics, symptoms (Pruritus, Jaundice, cholangitis), intra-op variables (cold ischemia time, blood transfusions, number of ducts used, etc.), peri-op complications [hepatic artery thrombosis (HAT), bile leak, infections], stricture morphology (length, donor and recipient duct diameters) and relevant laboratory data both pre- and post-endotherapy were studied. Favourable response to endotherapy was defined as symptomatic relief with > 80% reduction in total bilirubin/serum gamma glutamyl transferase. Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS 20.0.

Forty-one patients were included (age: 8-63 years). All had right lobe LDLT with duct-to-duct anastomosis. Twenty patients (48.7%) had favourable response to endotherapy. Patients with single duct anastomosis, aggressive stent therapy (multiple endoscopic retrograde cholagiography, upsizing of stents, dilatation and longer duration of stents) and an initial favourable response to endotherapy were independent predictors of good outcome (P < 0.05). Older donor age, HAT, multiple ductal anastomosis and persistent bile leak (> 4 wk post LT) were found to be significant predictors of poor response on multivariate analysis (P < 0.05).

Endoscopic therapy with aggressive stent therapy especially in patients with single duct-to-duct anastomosis was associated with a better outcome. Multiple ductal anastomosis, older donor age, shorter duration of stent therapy, early bile leak and HAT were predictors of poor outcome with endotherapy in these patients.

Core tip: Living donor liver transplantation (LDLT) is the definitive treatment for end stage liver disease. Biliary complications complicating LDLT is a major source of morbidity and mortality. Anastomotic strictures seen with LDLT are notorious for gross phenotypical variations which have led to variable results with endotherapy as a treatment option in these patients. In this study, we have looked into the factors that can predict the response with endotherapy (endoscopic retrograde cholangiography, sphincterotomy and stent placement) thereby allowing for better prognostication and selection of patients in order to optimize patient care.

- Citation: Rao HB, Ahamed H, Panicker S, Sudhindran S, Venu RP. Endoscopic therapy for biliary strictures complicating living donor liver transplantation: Factors predicting better outcome. World J Gastrointest Pathophysiol 2017; 8(2): 77-86

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2150-5330/full/v8/i2/77.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4291/wjgp.v8.i2.77

Living donor liver transplantation (LDLT) as a treatment for end stage liver disease is an approach that is becoming increasingly common in Asian centres. Biliary complications, especially bile duct strictures (BDS), remain a significant complication of LDLT[1-4], although there seems to be a decline in incidence over the last 2 decades[5]. Unlike deceased donor liver transplantation (DDLT), the incidence of BDS in patients undergoing LDLT is higher and ranges between 18%-32%[6,7]. Most of these patients present with symptoms of bile duct obstruction such as jaundice, pruritus and/or cholangitis. Endotherapy with endoscopic retrograde cholangiography (ERC), sphincterotomy and placement of endoprosthesis have been shown to be technically feasible and safe for BDS in post LDLT[8,9]. However, therapeutic efficacy for BDS post LDLT has been variable[9-11]. Therefore, additional studies are needed looking into the factors that can predict a favourable therapeutic response to endotherapy.

The higher incidence of BDS post LDLT have been attributed to difficult surgical techniques of anastomosis owing to smaller diameter of the ducts along with multiple ductal anastomoses. The endotherapy protocol (type of stents, sphincterotomy, stricture dilatation, number of ERC with stent exchange and duration of stenting) has not been standardized in earlier reports, possibly accounting for the varying results of endotherapy in these studies[9-15]. The stricture morphology, type and number of stents used, duration of stent therapy may also have a direct bearing on therapeutic outcome. In this study various risk factors like anatomical contortions of the stricture, type and number of ductal anastomosis, duration, diameter as well as number of stents placed and their impact on the clinical as well as biochemical outcomes are carefully analysed.

This was a single centre, observational study where all patients referred to the Gastroenterology service with a diagnosis of BDS post LDLT from January 2012 till November 2015 were evaluated. Recipient and donor demographics (age and gender), transplant setting (emergency or elective), aetiology of liver disease, pre-operative Model for End-stage Liver Disease score, intra-operative variables like cold ischemia time, number of blood transfusions, number of bile ducts anastomosed, ductoplasty, conduit used (duct or jejunal loop) and post-operative complications like Hepatic artery thrombosis (HAT), bile leaks; were recorded in pre-designed performas. Bile leaks were considered persistent if the leak did not resolve in four weeks.

All patients who were medically fit to undergo therapeutic ERC were included in the study. All ERCs were performed by an experienced endoscopist under general anaesthesia and the choice of anaesthetic was left to the discretion of a dedicated anaesthetic doctor who was present throughout the duration for all procedures. A standard adult ERC scope (Olympus TJF Q180V) with an outer diameter of 13.7 mm and channel diameter of 4.2 mm was used. All procedures were performed in the endoscopy suite under fluoroscopic guidance (Fexavision, Shimadzu). Technical success was defined as selective cannulation of CBD with an adequate cholangiogram obtained. Definition of biliary stricture: Patients who had at least two of the three following features were included in the study: (1) Symptoms of cholestasis like Jaundice, pruritus and/or cholangitis in conjunction with elevated serum bilirubin and/or serum gamma glutamyl transferase (GGT) to more than twice the upper limit of normal; (2) Magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography showing a narrowing with proximal duct dilatation; and (3) ERC cholangiogram showing significant narrowing at the anastomotic site with/without ductal dilatation.

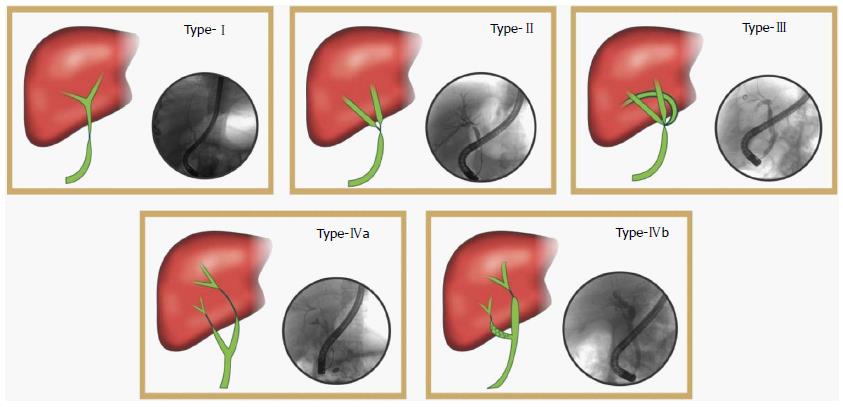

The cholangiograms were then reviewed for stricture morphology (length, diameter, type of anastomoses). The anastomoses were classified as type 1 when single donor duct was anastomosed to a single recipient duct. Type 2 is when two donor ducts are connected to a single recipient duct. Type 3 is when three donor ducts were anastomosed to a single recipient duct. Type 4 is when two recipient ducts (cystic duct and common hepatic duct or right and left hepatic ducts) are anastomosed with the donor duct (Figure 1). The number of ducts anastomosed including the use of cystic duct for anastomoses were also studied.

Therapeutic protocol and follow up: Institutional protocol for endoscopic management of benign biliary strictures includes Endoscopic sphincterotomy (5-7 mm), which was performed in all patients and stricture dilation using 4-7 mm balloon dilators were performed. A polyethylene stent of 5-7 Fr diameter and 12-15 cm long was then deployed across the stricture. The stent placement was repeated and the stent graduated to a higher diameter upto 10 Fr, if possible. The procedure was repeated every 3 mo for stent replacement for a minimum period of 1 year. Patients, who did not undergo this optimal stent exchange therapy for 1 year due to non-compliance, were studied for recurrence of symptoms and relevant laboratory studies at subsequent clinic visits.

Patients in whom ERC was unsuccessful (due to tight stricture or complex stricture), a guide wire was advanced into the duodenum across the stricture via a percutaneous trans hepatic puncture of the intrahepatic duct (PTBD). ERC, dilatation and stent placement was then carried out using a rendezvous approach. All patients were followed up for immediate and delayed complications.

Surgical repair was undertaken only when both endoscopic and transhepatic approaches failed to cross the stricture, the so called “defiant strictures”. Unlike BDS in deceased donors, those occurring in LDLT are surgically formidable to correct, since the length of donor duct (proximal to anastomosis) tends to be very short. BDS following LDLT therefore tend to extend intrahepatically and defining an appropriate donor duct for anastomosis can be a very formidable task surgically particularly in type 4 stictures.

Outcome was classified into favourable and unfavourable to endotherapy. Patients with favourable response had both biochemical and clinical improvement. Clinical improvement is characterised by relief from symptoms of bile duct obstruction (pruritus, jaundice and cholangitis) and biochemical improvement is considered when there was 80% reduction in total bilirubin (BR)/GGT. Unfavourable response was considered to be partial if either clinical or biochemical improvement was present and Non responsive if neither clinical nor biochemical improvement was seen.

Statistical analysis was carried out using IBM SPSS software version 20.0. Comparison of means in the three groups were done using ANOVA test for parametric or Kruskal Wallis for non-parametric variables. Response was also classified as complete responders and partial/No response where independent 2-sample t test and Mann Whitney U tests was used for parametric and non-parametric variables respectively. Categorical variables were analysed using χ2 test/Fisher’s Exact test in the univariate analysis. Multivariate analysis was then carried out using multiple logistic regression analysis. Kaplan Meier curves were computed to look for a survival advantage. A P value < 0.05 was taken as significant. The statistical methods of this study were reviewed by Mr Unnikrishnan UG, MSc Statistics, Lecturer, Department of Biostatistics, Amrita Institute of Medical Sciences, Kochi, Kerala, India.

Of the 458 LDLT performed, 47 patients had biliary strictures (10.2%); of which 41 patients had complete data and were included in the study. The mean age of the population was 40.02 ± 15.45 years with a male preponderance (87.8%). Majority of the patients were transplanted in a non-emergency setting (78%) with alcohol (37.5%) and cryptogenic (40.6%) cirrhosis being the most common etiologies for liver disease. The intra-operative variables did not have any association with therapeutic efficacy in this study. However, patients with post-operative HAT and BDS did not have any response to endotherapy despite re-establishment of flow in 4/5 patients. Majority (85.8%) of patients with persistent bile leak > 4 wk had only partial/no improvement to endotherapy (P value < 0.05). Demographic variables and baseline data are shown in Table 1.

| Parameters | Total (n = 41) | Complete response (n = 20) | Partial response (n = 14) | No response (n = 7) |

| Recipient mean age (year ± SD) | 40.02 ± 15.45 | 37.5 ± 17.03 | 41.0 ± 14.3 | 45.29 ± 13.15 |

| Donor mean age (year ± SD) | 39.9 ± 8.9 | 38.5 ± 6.85 | 39.86 ± 11.2 | 44.0 ± 9.03 |

| Recipient gender - male, n (%) | 36 (87.8) | 16 (80) | 14 (100) | 6 (85.7) |

| Donor gender - male, n (%) | 9 (22) | 4 (20) | 4 (28.5) | 1 (14.2) |

| Transplant setting, n (%) | ||||

| CLD | 32 (78) | 14 (70) | 12 (85.7) | 6 (85.7) |

| ALF | 9 (22) | 6 (30) | 2 (14.3) | 1 (14.3) |

| Etiology of CLD (n = 32) | ||||

| Alcohol | 12 (37.5) | 4 (33.3) | 6 (50) | 2 (16.7) |

| Cryptogenic | 13 (40.6) | 6 (46.1) | 5 (38.4) | 2 (15.5) |

| Others (Wilsons, hepatitis B, hepatitis C, autoimmune) | 7 (21.8) | 3 (42.8) | 2 (28.6) | 2 (28.6) |

| MELD | 23.45 ± 6.4 | 25.07 ± 7.2 | 22.46 ± 4.75 | 21.83 ± 6.52 |

| Intra-operative variables | ||||

| Cold Ischemia time (secs) (mean ±) | 51.5 ± 29.2 | 53.3 ± 34.4 | 54.08 ± 25.6 | 43.57 ± 28.4 |

| Blood transfusions (mean ±) | 4.1 ± 2.8 | 4.3 ± 2.3 | 4.3 ± 3.5 | 3.2 ± 2.2 |

| Post op complications | ||||

| Hepatic artery thrombosis, n (%) | 5 (12.2) | 0 (0) | 3 (60) | 2 (40) |

| Bile leak | 26 (65) | 12 (60) | 10 (71.4) | 4 (57.1) |

| Mean interval between LT and leak (d) | 18.4 | 20.85 | 12.6 | 5.6 |

| Persistent bile leak > 4 wk, n (%) | 14 (34.1) | 2 (14.2) | 8 (57.1) | 4 (28.7) |

| Clinical presentation, n (%) | ||||

| Cholangitis | 15 (36.6) | 6 (30) | 7 (42.1) | 2 (13.4) |

| Pruritus alone | 16 (39) | 7 (43.75) | 4 (25) | 5 (31.25) |

| Jaundice | 16 (39) | 5 (31.25) | 6 (37.5) | 5 (31.25) |

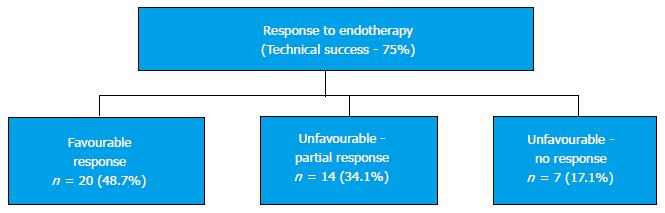

ERCP was successful in 31 patients (75.6%) while 10 patients (24.4%) required a combined PTBD with a rendezvous approach. Favourable response to endotherapy was seen in 20 patients (48.7%); 14 patients (34.1%) had partial unfavourable response to endotherapy and 7 patients (17.1%), had no response to endotherapy (Figure 2).

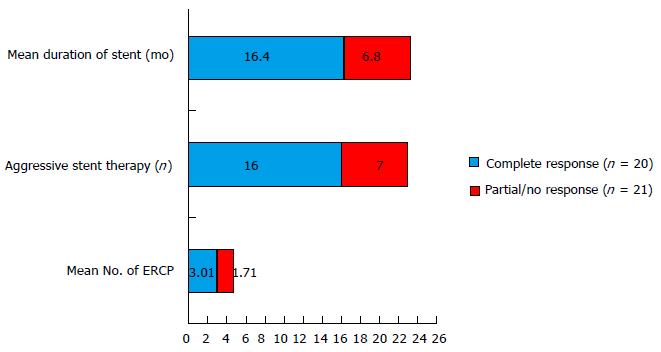

A total of 117 ERCPs were performed in 41 patients (2.8 procedures per patient) (Table 2). Patients who had complete improvement to endotherapy (favourable response) had a significantly higher number of total ERC (3.01 in patients with favourable response whereas 1.71 in patients with unfavourable response) and the initial favourable response to endotherapy was also higher (85% vs 57.1% respectively) (P < 0.05) in these patients. Aggressive stent therapy was performed in 23 patients (56%) and these patients had a significant improvement after endotherapy, 16 patients (69.5%) had complete favourable response while 7 patients (30.5%) had partial/no improvement (P value 0.04). Duration of stent therapy showed a direct impact on therapeutic efficacy where patients with a favourable response to endotherapy having the stent in place for a mean duration of 16.4 mo, whereas, patients who had a partial/no response to endotherapy had the stent in place for a mean duration of 6.8 mo (P value = 0.03) (Figure 3). A minimum duration of 6.75 mo of stent therapy was found to be predictive of a favourable response to endotherapy (AUROC 0.75).

| Endotherapy details | Total (n = 41) | Complete response (n = 20) | Partial/no response (n = 21) |

| Mean time interval between LT and first ERC (d) | |||

| Mean No. of ERCa | 368.3 | 352.6 | 444.1 |

| Mean Stricture length (cm) | 2.85 | 3.01 | 1.71 |

| Initial response to ERC, n (%) | 0.84 | 0.85 | 0.82 |

| Aggressive stent therapyab | 29 (70.7) | 17 (85) | 12 (57.1) |

| Mean duration of stentinga (mo) | 23 (39) | 16 (69.5) | 7 (23.3) |

| Morphology of the stricture | 5.75 | 16.4 | 6.8 |

| Mean length of stricture (mm) | 84 | 82 | 85 |

| Type of anastomosis (Figure 1), n (%) | |||

| Type I | 13 | 10 (76.9) | 3 (23.1) |

| Type II | 16 | 9 (56.25) | 7 (43.75) |

| Type III | 5 | 1 (20) | 4 (80) |

| Type IV | 7 | 0 (14.2) | 7 (100) |

Stricture morphology: Stricture length and duct diameters did not have a significant correlation to eventual response to endotherapy. The type of anastomosis, however (Figure 1), did influence the response to endotherapy. All patients with type IV (2 recipient ducts) anastomosis had a poor response to endotherapy (Table 2).

Surgical repair was performed only for one patient in this cohort, who remains well following surgery. In one other patient, who developed secondary biliary cirrhosis, retransplantation was required.

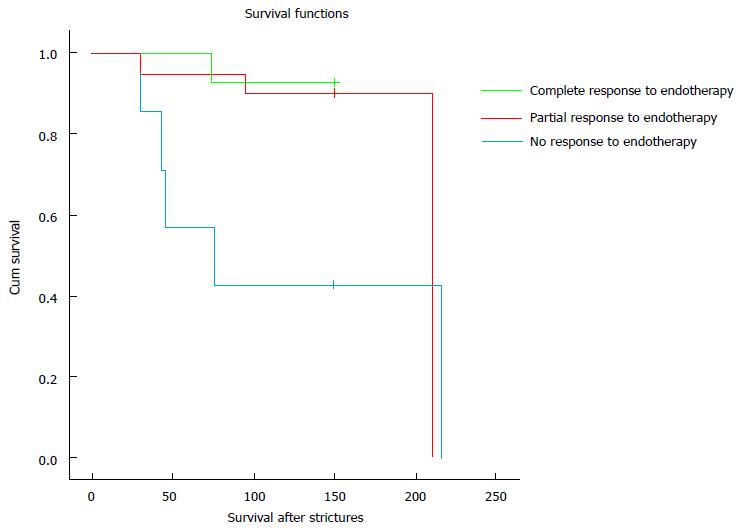

Endotherapy in this patient cohort was safe and only 1 patient had mild acute pancreatitis and 1 patient had cholangitis. A total of 9 patients died (21.9%), including the one with cholangitis. However, a statistically significant survival advantage was observed in patients who had a favourable response to endotherapy as opposed to patients who did not (P value 0.02) (Figure 4).

Liver transplantation remains the only definitive treatment for end stage liver disease. Transplantation using living donors, which is commonly practised in most Asian centres including India, is fraught with unique technical challenges and specific complications with as yet, evolving avenues of therapy. Biliary complications (BDS and Bile leaks) in particular, continue to be a stumbling block resulting in considerable morbidity and mortality among these patients[2,16-18]. The incidence of BDS is higher in LDLT patients (10%-30%) compared to DDLT possibly related to smaller diameter of the ducts and multiple ductal anastomoses[19,20].

BDS in the post-transplant setting is classified into one of two types - anastomotic (AS) and non-anastomotic (NAS) strictures. NAS, more common with DDLT, with an incidence of 5%-15%[17,18] are longer, multiple and located proximal to the anastomotic site. NAS are further divided into microangiopathic (with prolonged cold ischemia times), macroangiopathic (in association with HAT) and immunogenic (in association with rejection). AS on the other hand, are seen more frequently in patients who have received living donor livers and tend to be shorter, confined to the anastomotic site and present later in the course of follow up[5]. Multiple factors contribute to the development of AS including surgical technique, number of ducts anastomosed and ischemia[21]. The complexity of the microvasculature of the bile ducts makes them particularly vulnerable to ischemia. Management of biliary strictures with endotherapy, i.e., ERC with endobiliary stenting, is the treatment of choice especially for patients with AS[22]. They are notoriously difficult to treat with a recurrence rate between 9%-37%[23]. However, contrary to this, a report from the Adult-to-Adult Living Donor Liver Transplantation Cohort Study consortium (A2ALL)[24] suggested a comparable efficacy of endoscopic treatment in anastomotic strictures (in both DDLT as well as LDLT setting) based on which a recommendation to reserve endoscopic therapy as a first line treatment for all patients with anastomotic strictures could be made[22]. Unfortunately, some of these patients may not have a favourable response to endotherapy resulting in significant morbidity and even mortality. These patients with the so-called “defiant” biliary strictures may end up with re-surgery or repeat transplantation which will add to the financial burden of the patients[22].

Several investigators have reported a favourable response following endotherapy in the range of 53%-88%[3,19,25,26]. In our patient population, a favourable response was seen in only 48.7% of patients, while partial relief(clinical or biochemical) was noted in 34.1% of patients. Seven/41 patients (17.1%) in our study had no response to endotherapy. Moreover patients who did not respond to endotherapy were at a survival disadvantage with high mortality rate. This critical observation provided us with the impetus to study the factors that might predict outcome with endotherapy, especially since there is a considerable variation of results and lack of uniform treatment protocols.

Donor age was found to have a significant bearing on response to endotherapy. The age related variations in duct calibre and fibrotic response to ischemia/inflammation of the ducts may be possible pathogenic factors for the development of complex BDS. HAT in the post-operative period was a significant predictor of poor response to endotherapy despite re-establishment of flow in most of the patients (4/5 patients, 80%). This suggests that the ischemic stress even though “short-lived” was sufficient to significantly compromise the viablity of the anastomotic site leading to complex and defiant strictures.

Bile leaks have previously been shown to be associated with an increased incidence of BDS[27-29]. Inflammatory reactions due to the extravasated bile leading to fibrosis has been proposed as the pathogenetic mechanism in these patients. Alternatively, bile leak may be a surrogate to indicate ischemia and necro inflammatory reaction which eventually results in BDS[30]. Our study looked into not just the immediate perioperative bile leak but also the duration of leak, of more than 4 wk. Patients who had persistent bile leak more than four weeks had a poor outcome following endotherapy which may in part, be related to a dose response relationship between persistent inflammation caused by the extravasated bile. As a corollary to this, an early and aggressive treatment protocol with endoscopic sphincterotomy and stent placement may positively impact endoscopic outcome for BDS in these patients.

LDLT strictures are notoriously complex possibly resulting from multiple ductal anastomoses, mismatch of duct sizes and altered anatomy[31]. Only 75% technical success rate was achieved with ERC in our patient population with 10 patients requiring PTBD followed by rendezvous approach for stent placement. In all these patients the strictures assumed complex anatomical contortions.

Multiple ductal anastomoses are seldom considered as a risk factor for BDS post LDLT[32]. In a study by Chan et al[33], they found that a single hepatic duct is ideal for a duct to duct anastomosis. If two ducts are present, a duct to duct anastomosis can still be performed provided the ducts are less than 3 mm apart. If the ducts are more than 3 mm apart, they suggested separate Hepaticojejunostomies using a Roux-en-T loop[33]. Another study by Asonuma et al[34] explored the feasibility of the use of the recipient cystic duct for biliary reconstruction in right liver donor transplantation when two bile duct orifices were present. Our study also revealed that employing multiple recipient ducts for anastomosis can cause defiant and complex strictures resistant to endotherapy. Moreover when recipient cystic duct was used for anastomosis, the outcome for endotherapy was especially poor. The stricture length did not correlate with response to endotherapy suggesting a complex anatomical spatial alteration as the likely cause for poor response to endotherapy than longitudinal extent of the stricture.

There is no uniform consensus on the ERC protocol for the treatment of post LDLT BDS. Several reports have suggested that balloon dilatation with endobiliary stenting is superior to dilatation alone[17,35-37]. However, in a meta-analysis published recently, balloon dilatation with stenting did not afford a significant advantage to dilatation alone[38]. Current practices for management of BDS post LDLT suggests a 3 mo interval for repeat procedures with stricture dilatation and stent exchanges, which has been shown to minimize stent occlusion and prevent cholangitis or stone formation[17,22,39]. Our results also indicate that an aggressive endotherapy protocol which included stent exchanges every 3 mo, stent up-sizing to a maximum of 10 Fr, serial dilatation of the strictures and prolonged duration of stent therapy were associated with a favourable response to endotherapy. Similar to our experience Verdonk et al[30] had a 75% success rate for post LDLT strictures with a median of 3 endotherapy sessions per patient. They also showed that higher number of endotherapy sessions with increasing number of stents had a good outcome. A predictive cut-off of 6.75 mo for the duration of stent therapy was found to have reasonable validity for eventual favourable response to endotherapy. Most studies in this area have found an average stent duration between 6 mo to 1 year with 3-4 endotherapy sessions to be adequate in preventing recurrences with minimal complications and morbidity[7,40,41].

Reported complications for endotherapy in BDS post transplantation include post-ERC pancreatitis, cholangitis, bleeding, pain and stent migration. In this study, ERC followed by endotherapy was found to be safe with only one patient developing mild acute pancreatitis and one developing cholangitis. Premature removal of stents without replacement or up-sizing of stent was associated with recurrent bile duct stricture and cholestatic jaundice.

The treatment of “defiant” BDS remains an elusive area of study where innovative endoscopic approaches like the use of digital single operator cholangioscopy (DSOC)[42], covered self-expanding metallic stent (c-SEMS)[43], use of multiple plastic stents and novel dilatation balloons[22] are steadily gaining ground over traditional eventual surgical options which include hepaticojejunostomy and retransplantation[22,44]. In this study, 2 patients with “defiant” BDS underwent surgery [Hepaticojejunostomy (1) and Retransplantation (1)] and one patient had a c-SEMS placed. The use of c-SEMS has recently been studied in a meta-analysis[38] where it was shown to have superior efficacy rates as compared to multiple plastic stenting. However, the same analysis showed high complication rates, especially stent migration[38]. In our study, 2 patients with difficult BDS underwent DSOC with the help of which we were able to traverse the stricture successfully only in 1 patient. Our approach to “defiant” BDS currently centres around the use of multiple plastic stents with only selected patients receiving c-SEMS. Surgical correction is reserved for patients who have particularly crippling symptoms along with frequent recurrence of strictures despite maximal stent therapy for over a period of 15 mo.

In summary, BDS remains a major complication of LDLT. Early identification of risk factors such as bile leaks and HAT in conjunction with adopting early treatment measures may improve therapeutic efficacy of endotherapy in these patients. Aggressive endotherapy protocols seem to have a favourable outcome after endotherapy thereby reducing the associated morbidity and mortality of BDS post LDLT. The use of c-SEMS, DSOC in the management of “defiant” BDS is an area that requires further study.

Bile duct strictures (BDS) are a major cause of morbidity and mortality in patients who have undergone a living donor liver transplantation. Endotherapy for BDS in these patients includes endoscopic retrograde cholangiography, sphincterotomy and stent placement. Results of endotherapy are variable and factors predicting outcome are not well elucidated.

Factors that can predict endotherapy outcome and result in optimal patient selection. Endotherapy protocols/guidelines which can help roadmap this heterogenous group of patients towards better healthcare.

Unique outcome definition: The outcome of endotherapy was considered favourable only when there was symptomatic and biochemical improvement. Partial responders were considered unfavourable owing to significant morbidity in this group. This sub group of patients is particulary tricky as they find themselves in a therapeutic “no man’s land” so to speak, where established treatment has provided some improvement, but with residual yet significant morbidity. Aggressive endotherapy protocols with repeated procedures, serial dilatation and stent upsizing for a minimum period exceeding 6 mo can yield good outcomes in majority of patients. Early endotherapy in patients with persistent bile leak (> 4 wk) may prevent the development of complex BDS. Use of two or more recipient ducts, especially cystic ducts are particularly poor responders to endotherapy.

This study may aid in the establishment of uniform endotherapy protocols which can have a wide applicability beyond the confines of single centre experiences. Bile duct anastomosis using multiple recipient ducts may be avoided, if possible; in favour of innovative surgical practices that may impact overall outcome in these patients. The outcome definition which identifies partial responders may suggest a sub group that needs a more detailed assessment which can lend clarity on optimal management of these patients.

Type of anastomosis has been classified in terms of number of anastomosis into 4 types which have a significant bearing on overall outcome. Outcome definition was defined as favourable (symptomatic and biochemical improvement) and unfavourable (partial/non responders). Partial responders are those with either symptomatic and biochemical improvement and non-responders were labelled as those with neither.

The manuscript focuses on the endoscopic treatment of biliary strictures in living donor liver transplantation. It is interesting and well written.

Manuscript source: Invited manuscript

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country of origin: India

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): D

Grade E (Poor): 0

P- Reviewer: De Carlis R, Kim SM, Wejman J S- Editor: Ji FF L- Editor: A E- Editor: Wu HL

| 1. | Wang SF, Huang ZY, Chen XP. Biliary complications after living donor liver transplantation. Liver Transpl. 2011;17:1127-1136. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 83] [Cited by in RCA: 89] [Article Influence: 6.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Dulundu E, Sugawara Y, Sano K, Kishi Y, Akamatsu N, Kaneko J, Imamura H, Kokudo N, Makuuchi M. Duct-to-duct biliary reconstruction in adult living-donor liver transplantation. Transplantation. 2004;78:574-579. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 94] [Cited by in RCA: 87] [Article Influence: 4.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Gondolesi GE, Varotti G, Florman SS, Muñoz L, Fishbein TM, Emre SH, Schwartz ME, Miller C. Biliary complications in 96 consecutive right lobe living donor transplant recipients. Transplantation. 2004;77:1842-1848. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 179] [Cited by in RCA: 184] [Article Influence: 8.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Ramacciato G, Varotti G, Quintini C, Masetti M, Di Benedetto F, Grazi GL, Ercolani G, Cescon M, Ravaioli M, Lauro A. Impact of biliary complications in right lobe living donor liver transplantation. Transpl Int. 2006;19:122-127. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Simoes P, Kesar V, Ahmad J. Spectrum of biliary complications following live donor liver transplantation. World J Hepatol. 2015;7:1856-1865. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 47] [Cited by in RCA: 47] [Article Influence: 4.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Gómez CM, Dumonceau JM, Marcolongo M, de Santibañes E, Ciardullo M, Pekolj J, Palavecino M, Gadano A, Dávolos J. Endoscopic management of biliary complications after adult living-donor versus deceased-donor liver transplantation. Transplantation. 2009;88:1280-1285. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 58] [Cited by in RCA: 62] [Article Influence: 3.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Thuluvath PJ, Pfau PR, Kimmey MB, Ginsberg GG. Biliary complications after liver transplantation: the role of endoscopy. Endoscopy. 2005;37:857-863. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 157] [Cited by in RCA: 153] [Article Influence: 7.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Chok KS, Chan SC, Cheung TT, Sharr WW, Chan AC, Fan ST, Lo CM. A retrospective study on risk factors associated with failed endoscopic treatment of biliary anastomotic stricture after right-lobe living donor liver transplantation with duct-to-duct anastomosis. Ann Surg. 2014;259:767-772. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Tsujino T, Isayama H, Sugawara Y, Sasaki T, Kogure H, Nakai Y, Yamamoto N, Sasahira N, Yamashiki N, Tada M. Endoscopic management of biliary complications after adult living donor liver transplantation. Am J Gastroenterol. 2006;101:2230-2236. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 107] [Cited by in RCA: 114] [Article Influence: 6.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Kato H, Kawamoto H, Tsutsumi K, Harada R, Fujii M, Hirao K, Kurihara N, Mizuno O, Ishida E, Ogawa T. Long-term outcomes of endoscopic management for biliary strictures after living donor liver transplantation with duct-to-duct reconstruction. Transpl Int. 2009;22:914-921. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 58] [Cited by in RCA: 65] [Article Influence: 4.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Kurita A, Kodama Y, Minami R, Sakuma Y, Kuriyama K, Tanabe W, Ohta Y, Maruno T, Shiokawa M, Sawai Y. Endoscopic stent placement above the intact sphincter of Oddi for biliary strictures after living donor liver transplantation. J Gastroenterol. 2013;48:1097-1104. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 47] [Article Influence: 3.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 12. | Lee YY, Gwak GY, Lee KH, Lee JK, Lee KT, Kwon CH, Joh JW, Lee SK. Predictors of the feasibility of primary endoscopic management of biliary strictures after adult living donor liver transplantation. Liver Transpl. 2011;17:1467-1473. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 41] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Chang JH, Lee IS, Choi JY, Yoon SK, Kim DG, You YK, Chun HJ, Lee DK, Choi MG, Chung IS. Biliary Stricture after Adult Right-Lobe Living-Donor Liver Transplantation with Duct-to-Duct Anastomosis: Long-Term Outcome and Its Related Factors after Endoscopic Treatment. Gut Liver. 2010;4:226-233. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 69] [Cited by in RCA: 82] [Article Influence: 5.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Kim ES, Lee BJ, Won JY, Choi JY, Lee DK. Percutaneous transhepatic biliary drainage may serve as a successful rescue procedure in failed cases of endoscopic therapy for a post-living donor liver transplantation biliary stricture. Gastrointest Endosc. 2009;69:38-46. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 59] [Cited by in RCA: 59] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Kim TH, Lee SK, Han JH, Park DH, Lee SS, Seo DW, Kim MH, Song GW, Ha TY, Kim KH. The role of endoscopic retrograde cholangiography for biliary stricture after adult living donor liver transplantation: technical aspect and outcome. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2011;46:188-196. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 39] [Cited by in RCA: 46] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Duffy JP, Kao K, Ko CY, Farmer DG, McDiarmid SV, Hong JC, Venick RS, Feist S, Goldstein L, Saab S. Long-term patient outcome and quality of life after liver transplantation: analysis of 20-year survivors. Ann Surg. 2010;252:652-661. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 195] [Cited by in RCA: 202] [Article Influence: 13.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Sharma S, Gurakar A, Jabbour N. Biliary strictures following liver transplantation: past, present and preventive strategies. Liver Transpl. 2008;14:759-769. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 263] [Cited by in RCA: 275] [Article Influence: 16.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Graziadei IW, Schwaighofer H, Koch R, Nachbaur K, Koenigsrainer A, Margreiter R, Vogel W. Long-term outcome of endoscopic treatment of biliary strictures after liver transplantation. Liver Transpl. 2006;12:718-725. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 147] [Cited by in RCA: 157] [Article Influence: 8.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Ribeiro JB, Martins Fde S, Garcia JH, Cunha AC, Pinto RA, Satacaso MV, Prado-Júnior FP, Pessoa RR. Endoscopic management of biliary complications after liver transplantation. Arq Bras Cir Dig. 2012;25:269-272. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Lee DW, Jo HH, Abdullah J, Kahaleh M. Endoscopic Management of Anastomotic Strictures after Liver Transplantation. Clin Endosc. 2016;49:457-461. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Seehofer D, Eurich D, Veltzke-Schlieker W, Neuhaus P. Biliary complications after liver transplantation: old problems and new challenges. Am J Transplant. 2013;13:253-265. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 199] [Cited by in RCA: 215] [Article Influence: 17.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Shin M, Joh JW. Advances in endoscopic management of biliary complications after living donor liver transplantation: Comprehensive review of the literature. World J Gastroenterol. 2016;22:6173-6191. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 4.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Koh PS, Chan SC. Adult-to-adult living donor liver transplantation: Operative techniques to optimize the recipient’s outcome. J Nat Sci Biol Med. 2017;8:4-10. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Zimmerman MA, Baker T, Goodrich NP, Freise C, Hong JC, Kumer S, Abt P, Cotterell AH, Samstein B, Everhart JE. Development, management, and resolution of biliary complications after living and deceased donor liver transplantation: a report from the adult-to-adult living donor liver transplantation cohort study consortium. Liver Transpl. 2013;19:259-267. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 79] [Cited by in RCA: 90] [Article Influence: 7.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Wadhawan M, Kumar A, Gupta S, Goyal N, Shandil R, Taneja S, Sibal A. Post-transplant biliary complications: an analysis from a predominantly living donor liver transplant center. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013;28:1056-1060. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 39] [Cited by in RCA: 45] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Yazumi S, Yoshimoto T, Hisatsune H, Hasegawa K, Kida M, Tada S, Uenoyama Y, Yamauchi J, Shio S, Kasahara M. Endoscopic treatment of biliary complications after right-lobe living-donor liver transplantation with duct-to-duct biliary anastomosis. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg. 2006;13:502-510. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 98] [Cited by in RCA: 103] [Article Influence: 5.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Ostroff JW. Post-transplant biliary problems. Gastrointest Endosc Clin N Am. 2001;11:163-183. [PubMed] |

| 28. | Bourgeois N, Deviére J, Yeaton P, Bourgeois F, Adler M, Van De Stadt J, Gelin M, Cremer M. Diagnostic and therapeutic endoscopic retrograde cholangiography after liver transplantation. Gastrointest Endosc. 1995;42:527-534. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 61] [Cited by in RCA: 60] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Krok KL, Cárdenas A, Thuluvath PJ. Endoscopic management of biliary complications after liver transplantation. Clin Liver Dis. 2010;14:359-371. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 37] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Verdonk RC, Buis CI, Porte RJ, van der Jagt EJ, Limburg AJ, van den Berg AP, Slooff MJ, Peeters PM, de Jong KP, Kleibeuker JH. Anastomotic biliary strictures after liver transplantation: causes and consequences. Liver Transpl. 2006;12:726-735. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 214] [Cited by in RCA: 236] [Article Influence: 12.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Freise CE, Gillespie BW, Koffron AJ, Lok AS, Pruett TL, Emond JC, Fair JH, Fisher RA, Olthoff KM, Trotter JF. Recipient morbidity after living and deceased donor liver transplantation: findings from the A2ALL Retrospective Cohort Study. Am J Transplant. 2008;8:2569-2579. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 236] [Cited by in RCA: 213] [Article Influence: 12.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Salvalaggio PR, Whitington PF, Alonso EM, Superina RA. Presence of multiple bile ducts in the liver graft increases the incidence of biliary complications in pediatric liver transplantation. Liver Transpl. 2005;11:161-166. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 40] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Chan SC, Fan ST. Biliary complications in liver transplantation. Hepatol Int. 2008;2:399-404. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Asonuma K, Okajima H, Ueno M, Takeichi T, Zeledon Ramirez ME, Inomata Y. Feasibility of using the cystic duct for biliary reconstruction in right-lobe living donor liver transplantation. Liver Transpl. 2005;11:1431-1434. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Zoepf T, Maldonado-Lopez EJ, Hilgard P, Malago M, Broelsch CE, Treichel U, Gerken G. Balloon dilatation vs. balloon dilatation plus bile duct endoprostheses for treatment of anastomotic biliary strictures after liver transplantation. Liver Transpl. 2006;12:88-94. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 133] [Cited by in RCA: 128] [Article Influence: 6.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Morelli J, Mulcahy HE, Willner IR, Cunningham JT, Draganov P. Long-term outcomes for patients with post-liver transplant anastomotic biliary strictures treated by endoscopic stent placement. Gastrointest Endosc. 2003;58:374-379. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 142] [Cited by in RCA: 136] [Article Influence: 6.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Park JS, Kim MH, Lee SK, Seo DW, Lee SS, Han J, Min YI, Hwang S, Park KM, Lee YJ. Efficacy of endoscopic and percutaneous treatments for biliary complications after cadaveric and living donor liver transplantation. Gastrointest Endosc. 2003;57:78-85. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 148] [Cited by in RCA: 161] [Article Influence: 7.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | Aparicio DPDS, Otoch JP, Montero EFDS, Khan MA, Artifon ELDA. Endoscopic approach for management of biliary strictures in liver transplant recipients: A systematic review and meta-analysis. United Eur Gastroent. 2016;0:1-19. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | Buxbaum JL, Biggins SW, Bagatelos KC, Ostroff JW. Predictors of endoscopic treatment outcomes in the management of biliary problems after liver transplantation at a high-volume academic center. Gastrointest Endosc. 2011;73:37-44. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 40. | Balderramo D, Navasa M, Cardenas A. Current management of biliary complications after liver transplantation: emphasis on endoscopic therapy. Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011;34:107-115. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 47] [Cited by in RCA: 46] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 41. | Venu M, Brown RD, Lepe R, Berkes J, Cotler SJ, Benedetti E, Testa G, Venu RP. Laboratory diagnosis and nonoperative management of biliary complications in living donor liver transplant patients. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2007;41:501-506. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 42. | Balderramo D, Sendino O, Miquel R, de Miguel CR, Bordas JM, Martinez-Palli G, Leoz ML, Rimola A, Navasa M, Llach J. Prospective evaluation of single-operator peroral cholangioscopy in liver transplant recipients requiring an evaluation of the biliary tract. Liver Transpl. 2013;19:199-206. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 43. | Kaffes A, Griffin S, Vaughan R, James M, Chua T, Tee H, Dinesen L, Corte C, Gill R. A randomized trial of a fully covered self-expandable metallic stent versus plastic stents in anastomotic biliary strictures after liver transplantation. Therap Adv Gastroenterol. 2014;7:64-71. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 96] [Cited by in RCA: 115] [Article Influence: 10.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 44. | Kao D, Zepeda-Gomez S, Tandon P, Bain VG. Managing the post-liver transplantation anastomotic biliary stricture: multiple plastic versus metal stents: a systematic review. Gastrointest Endosc. 2013;77:679-691. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 97] [Cited by in RCA: 110] [Article Influence: 9.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |