Published online Aug 15, 2016. doi: 10.4291/wjgp.v7.i3.283

Peer-review started: March 23, 2016

First decision: April 15, 2016

Revised: April 28, 2016

Accepted: May 17, 2016

Article in press: May 27, 2016

Published online: August 15, 2016

Processing time: 141 Days and 0.4 Hours

AIM: To determine reproducibility of perioperative chemotherapy for gastric cancer (GC) on our settings by identifying patient’s overall survival and comparing them to larger studies.

METHODS: Retrospective analysis of our series, where we present our eleven-year’s experience on GC managed according to perioperative approach of three preoperative chemotherapy cycles followed by surgery and finally three postoperative chemotherapy cycles. Chemotherapic scheme used was Xelox (Oxaliplatin and Capecitabine). Epidemiologic parameters as well as surgical variables were analysed, presented, and compared to other series with similar approaches. Survival was estimated by Kaplan Meier/log rank method and also compared to these studies.

RESULTS: Mean age was 65 years old. Overall survival in our series was 37.7%, similar to other groups using perioperative schemes. Mortality was 4% and morbidity 30%, which are also similar to those groups. Survival curves were compared to larger studies, finding similarities on them. Subgroup survival analysis between chemotherapy responders and non-responders didn’t reach statically significant differences.

CONCLUSION: Perioperative chemotherapic scheme can be reproduced on our setting with good results and without increasing morbidity or mortality.

Core tip: This is a retrospective study that evaluates and compares survival after perioperative chemotherapy on gastric cancer patients managed similarly in other settings. We confirmed reproducibility of this scheme on smaller settings than classic studies.

- Citation: León-Espinoza C, López-Mozos F, Marti-Obiol R, Garces-Albir M, Ortega-Serrano J. “Magic” of our gastric cancer results on perioperative chemotherapy. World J Gastrointest Pathophysiol 2016; 7(3): 283-287

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2150-5330/full/v7/i3/283.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4291/wjgp.v7.i3.283

Global gastric cancer’s (GC’s) incidence has notably change in western countries during the last decades. Nowadays, GC stands for about 6.8% of all cancers, and represents about 8.8% of all deaths for cancer. Among all cancers, it is the fourth on incidence in men and the fifth in women, and is the third and fifth cause of cancer deaths in men and women respectively[1].

GC’s survival mostly depends on stage at time of diagnosis. The 5-year survival after radical surgery on a localized GC is about 70%-95%, while metastatic disease’s survival reaches about 3-4 mo.

Surgery is the only curative treatment for GC. Either total or partial gastrectomies associated to lymphadenectomy are the gold standard. Local, regional and distant recurrence may occur despite a correct oncologic resection. Therefore, medical therapy against micro-metastasis is crucial. Several treatment schemes have developed during the pre-, peri- and post-operatory phases in order to improve long term survival. Perioperative treatment is a common scheme with proofed efficacy, but concern about disease progression by delaying surgery and increased surgical morbidity has also developed.

In our unit we use a pre- and post-operatory chemotherapy (QT) scheme following recommendations published by Cunningham et al[2], assuming it has long-term benefits, with an acceptable morbidity and mortality rates.

This retrospective review aimed to describe the overall survival as our primary endpoint and compare it with previous publications. Secondary endpoints were: Analysis of clinical response after perioperative chemotherapy, postoperative morbidity/mortality and re-intervention rates, comparing them to papers published previously by other groups using a similar approach.

Patients included in our database were introduced prospectively since 2004, after multidisciplinary esophago-gastric unit was created. From a total of 211 patients diagnosed of GC, ninety-nine received perioperative QT and were analyzed. The excluded 112 patients were either T1-2 N0 M0 or had metastatic disease. Epidemiologic variables are described on Table 1, including Age, gender, and clinical stage.

| n | % | ||

| Gender | Male | 74 | 74.7 |

| Female | 25 | 25.3 | |

| Clinical stage | II | 24 | 24.2 |

| IIIa | 57 | 57.6 | |

| IIIb | 18 | 18.2 | |

| Age | 65 ± 9 yr | ||

GC’s diagnosis was based on endoscopic-biopsy results. We assessed the extension by performing a CT scan and endoscopic ultrasonography (EUS). Some particular cases needed further explorations as MRI, PET-CT or diagnostic laparoscopy. TNM sixth edition classification was used to determine clinical stage[3].

Once identified, we included patients catalogued as T3-T4 and/or N (+), without distant disease and started perioperative Chemotherapy based on Xelox (Oxaliplatin and Capecitabine). They received 3 cycles preoperatively and 3 cycles at least 6 wk after surgery, depending on performance status.

Variables as surgical technique, surgical intention, post-operatory morbidity, re-intervention rate and post-operatory mortality (starting on surgery until 30 d after hospital dismiss) were analyzed. Reassessment of stage was performed 2 wk after last pre-operatory chemotherapy cycle, and classified as follows: (1) complete regression; (2) partial regression; (3) stable disease/no response; and (4) progressive disease, following recommendations published on RECIST guideline (version 1.1)[4].

Survival estimation was analyzed by Kaplan-Meier/log rank method comparing subgroups of patients with response (Complete and Partial regression) and without response (Stable or progressive disease) to pre-operative QT, and comparing results to similar previous trials.

Mean age on our group was 65 ± 9 years, divided on 74 (74.7%) male and 25 female (25.3%). Distribution of preoperative clinical stage is specified on Table 1.

Open surgery was the rule for every patient who received preoperative QT. Surgery with curative intent was practiced on 78 patients, while palliative procedures were practiced on 21 patients.

Among all surgeries, we identified 34 distal gastrectomies, 53 total gastrectomies, 3 proximal gastrectomies, 3 gastro-jejunostomies and 6 exploratory laparotomies. D2 Lymphadenectomy was the rule for curative intent surgery. Extended resections for T4 tumors were performed on 20 patients.

Eighty percent of patients who received preoperative QT completed the programmed three cycles. Uncompleted cycles were due to several reasons (toxicity, patient decision, etc.). After reassessment we found that 4 patients had a complete response, 55 had partial response, 35 had a stable disease, and 5 presented progressive disease, following the criteria of RECIST Guidelines[4].

After surgery, 30 patients had complications, which represented 30% of study group. Most of them were either superficial surgical site infections (9 patients) or cardio-pulmonary disorders (10 patients).

Nineteen patients suffered from major surgical morbidities, finding six anastomotic leaks, two duodenal stump leaks, two acute intestinal obstructions, two iatrogenic small bowel perforations, four left sub-phrenic abscesses and three hemoperitoneums.

Due to mayor post-operatory complications, 6 patients underwent reoperation (Reoperation rate: 6%): One anastomotic leak, two iatrogenic perforations, one obstruction, one hemoperitoneum and one sub-phrenic abscess (managed initially percutaneous without improvement). The other patients having major surgical complications underwent medical, percutaneous or endoscopic management.

Mortality on post-operatory period was 4% (4 patients), secondary to peritonitis and multisystem failure after mayor surgical complications.

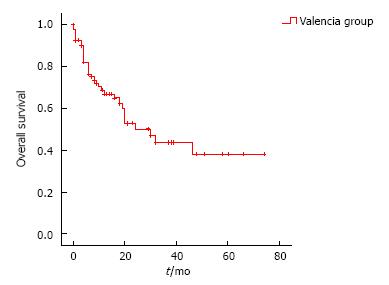

Mean follow up in patients who underwent surgery was 16.1 mo. Overall survival by Kaplan-Meier method was analyzed and represented on Figure 1. Mean survival was 37.7 ± 4.3 mo.

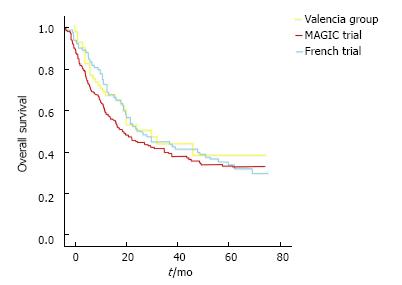

We also compared our survival curves with the ones published on MAGIC trial and French Group trial, finding similar results (Figure 2).

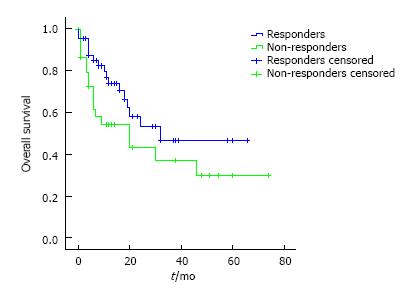

We compared subgroup survival, based on pre-operative chemotherapy response. Results are compared on Figure 3. This analysis failed to reach statistical differences (P = 0.1). During this time, fifteen recurrences were occurred. Between responders, 8 recurrences we detected, while on non-responders there were 7 recurrences.

Many strategies for improving survival on GC have been proposed during last years. Initially, surgery was considered the only beneficial treatment on GC management. The development of newer chemotherapic agents and their combination have opened some perspectives on survival improvement. Moreover, radiotherapy has also evolved, limiting side effects and minimizing radiation fields, becoming also an interesting alternative. When deciding on which therapy to choose for improving survival and the proper time to apply it, we must balance their benefits and disadvantages.

Neoadjuvant therapy has the theoretical advantage of allowing in vivo chemo-sensitivity tests, thus facilitating the choice of the most appropriate postoperative regimens. It can also increase compliance rate and maintain better nutritional status, while eliminating hidden micro-metastases and reducing tumor size[5].

On the other hand, preoperative therapy could delay surgical treatment increasing the risk of disease progression and increasing post operatory morbidity and mortality rates.

Another approach to chemotherapy is the post-operatory treatment. Adjuvant therapy has the advantage of immediate surgical excision with no chance of local progression. Nonetheless, surgery as first step of treatment has it’s own disadvantages. It can stimulate neoplastic proliferation, shorten tumor’s doubling time, decrease circulation/chemotherapy penetration on surgical bed and increase probability of chemo-resistant cellular clone development[6]. Adjuvant therapy also depends on performance status, which can be importantly altered after surgery.

Several meta-analyses have been conducted for identifying which therapy contributes better to both overall and disease-free survival. Initial studies on adjuvant therapy in western countries showed no benefits on overall or disease-free survival[7,8]. Nevertheless, on Asia, studies have concluded some benefits on patients receiving chemotherapy based on mitomycin (MMC), showing prolonged 5-year survival rate, becoming later MMC ± fluorouracile (FU) the standard regimen[9]. Further RCT have shown some advantages on adjuvant therapy based on capecitabine plus oxaliplatin in patients with stage II-IIIB GC[10].

Radiotherapy in addition to adjuvant chemotherapy is an approach supported by McDonald et al[11] on the Intergroup 0116 trial. It demonstrated overall and disease-free survival benefits and has been ratified by many smaller studies. Nevertheless, surgical quality on this trial has been criticized, based on low D2 or D1 rate. It has been also reported that adjuvant radio-chemotherapy has benefits over chemotherapy alone[12]. American NCCN guidelines recommend this regimen on patient’s tumors recognized as T2 or higher tumors, which didn’t receive preoperative treatment.

Perioperative chemotherapy is another regimen studied and supported. It was tested on Cunningham’s MAGIC trial, and details are described on his paper[2]. It has two phases; the first is a 3-cycle preoperative therapy, followed by surgery and finally another 3-cycle postoperative therapy.

Many benefits were recognized on this trial, starting from increased R0 surgeries without increasing complication rate, and increased overall and disease free survival.

A French trial[13] comparing perioperative chemotherapy with surgery alone, showed results similar to the ones obtained on MAGIC trial, confirming reproducibility of the first trial. As our team have surgical similarities with French and English groups and believe on potential benefits of preoperative chemotherapy, we included patients on this regimen since 2006.

On MAGIC trial primary endpoint was overall survival, reaching a significant improvement with a hazard ratio of 0.75 (95%CI: 0.6-0.93; P = 0.009) on favor of perioperative chemotherapy group. Five-year survival also showed improvement, prolonging survival from 23% on surgery alone group, to 36% on perioperative group.

In the last years some perspectives have arisen on treatment of advanced GC. Results on locally advanced GC and peritoneal carcinomatosis (PC) secondary to GC have still disappointing results, but researches on selected patients with advanced GC have been conducted during last years.

Due to advances on PC surgery, patients with CG have been included on protocols for complete cytoreductive surgery (CRS) and hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy, with encouraging results. Glehen et al[14] conducted a multicenter retrospective study on France, finding benefits on selected cases of PC from gastric origin, reaching a 13% on 5 year overall survival. Nevertheless, they recommend strict inclusion criteria such as limited seeding extension (PCI < 12), following response to neoadjuvant chemotherapy and with no diffuse small bowel involvement[14]. More recently an American group conducted a randomized controlled trial[15], comparing overall survival between patients following CRS and HIPEC and patients treated only with systemic chemotherapy. They also found overall survival benefits on CRS + HIPEC group, but emphasized on careful patient selection.

On our revision, overall survival was the primary endpoint and we found a 37.7%, which is similar to survival found by Cunningham on MAGIC trial, confirming reproducibility of MAGIC trial, and reassuring our confidence on the perioperative approach. We think that our follow up should be longer to let us conclude survival benefits.

Our complication rate (30%) reached percentages similar than other series, as Dutch Gastric Cancer trial (43%), German Gastric Cancer trial (22%) or MRC Gastric Cancer Surgical trial (46%).

Post-operatory mortality rate of 4% on our series is slightly inferior to previous published trials, which stay between 5%-13%. We performed subgroup analysis in order to establish if pre-operative tumor response to chemotherapy has implications on long-term survival rates. We couldn’t reach significant differences between both groups but detected a slight benefit in favor of responders. If this difference was real, patient might benefit of a different post-operative QT scheme. Further studies should be design to investigate on this issue.

In conclusion, perioperative therapy on GC in our institution, has similar survival rates as previous published papers, without increasing complication or mortality rates, supporting safe reproducibility of this approach. Survival benefits among patients categorized by preoperative response have not reached statically significant differences. Prolonged follow-up and increasing number of patients would be appropriate to met stronger conclusions.

Gastric cancer (GC) is one of the most prevalent and lethal neoplasia. Different approaches are currently followed around the world, with different results. Since the authors’ group started applying the MAGIC trial with the intent to reproduce their results in different settings and compare the final results with theirs.

The authors’ group supports perioperative approach as the best one available nowadays. Since started applying this scheme, the authors believed in its benefits and started on data collect for posterior analysis and local validation of this approach.

The theoretical risks of preoperative chemotherapy affecting surgical results, doesn’t reflect neither in morbidity nor in mortality rates. Survival rates obtained are similar to the ones published before, reassuring reproducibility of this scheme.

Application of this scheme in smaller settings as the authors, show similar results as emblematic studies of perioperative approach.

Perioperative chemotherapy is an oncologic approach consistent with pre-operative chemotherapy, followed by surgery and finally post-operative chemotherapy. On GC, this approach was described by Cunningham et al on his MAGIC trial, and supported by several posterior studies.

The author of this retrospective analysis aimed to evaluate effect of perioperative chemotherapy for GC. And authors found the conclusion that “perioperative chemotherapic scheme can be reproduced on the setting with good results and without increasing morbidity or mortality”. The authors raised up a valuable issue in this study. Also there were enough results to support opinion of authors.

Manuscript source: Invited manuscript

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country of origin: Spain

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P- Reviewer: Li Y, Ulasoglu C S- Editor: Ji FF L- Editor: A E- Editor: Lu YJ

| 1. | Torre LA, Bray F, Siegel RL, Ferlay J, Lortet-Tieulent J, Jemal A. Global cancer statistics, 2012. CA Cancer J Clin. 2015;65:87-108. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18694] [Cited by in RCA: 21363] [Article Influence: 2136.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (3)] |

| 2. | Cunningham D, Allum WH, Stenning SP, Thompson JN, Van de Velde CJ, Nicolson M, Scarffe JH, Lofts FJ, Falk SJ, Iveson TJ. Perioperative chemotherapy versus surgery alone for resectable gastroesophageal cancer. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:11-20. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4899] [Cited by in RCA: 4600] [Article Influence: 242.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Green FL, Page DL, Fleming ID, Fritz AG, Balch CM, Haller DG, Morrow M. AJCC Cancer Staging Manual. New York: Springer 2002; 99-106. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 4. | Eisenhauer EA, Therasse P, Bogaerts J, Schwartz LH, Sargent D, Ford R, Dancey J, Arbuck S, Gwyther S, Mooney M. New response evaluation criteria in solid tumours: revised RECIST guideline (version 1.1). Eur J Cancer. 2009;45:228-247. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15860] [Cited by in RCA: 21581] [Article Influence: 1348.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 5. | D'Ugo D, Rausei S, Biondi A, Persiani R. Preoperative treatment and surgery in gastric cancer: friends or foes? Lancet Oncol. 2009;10:191-195. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Fisher B, Gunduz N, Coyle J, Rudock C, Saffer E. Presence of a growth-stimulating factor in serum following primary tumor removal in mice. Cancer Res. 1989;49:1996-2001. [PubMed] |

| 7. | Coombes RC, Schein PS, Chilvers CE, Wils J, Beretta G, Bliss JM, Rutten A, Amadori D, Cortes-Funes H, Villar-Grimalt A. A randomized trial comparing adjuvant fluorouracil, doxorubicin, and mitomycin with no treatment in operable gastric cancer. International Collaborative Cancer Group. J Clin Oncol. 1990;8:1362-1369. [PubMed] |

| 8. | Macdonald JS, Fleming TR, Peterson RF, Berenberg JL, McClure S, Chapman RA, Eyre HJ, Solanki D, Cruz AB, Gagliano R. Adjuvant chemotherapy with 5-FU, adriamycin, and mitomycin-C (FAM) versus surgery alone for patients with locally advanced gastric adenocarcinoma: A Southwest Oncology Group study. Ann Surg Oncol. 1995;2:488-494. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 93] [Cited by in RCA: 87] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Lim L, Michael M, Mann GB, Leong T. Adjuvant therapy in gastric cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:6220-6232. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 113] [Cited by in RCA: 113] [Article Influence: 5.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Bang YJ, Kim YW, Yang HK, Chung HC, Park YK, Lee KH, Lee KW, Kim YH, Noh SI, Cho JY. Adjuvant capecitabine and oxaliplatin for gastric cancer after D2 gastrectomy (CLASSIC): a phase 3 open-label, randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2012;379:315-321. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1267] [Cited by in RCA: 1290] [Article Influence: 99.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Macdonald JS, Smalley SR, Benedetti J, Hundahl SA, Estes NC, Stemmermann GN, Haller DG, Ajani JA, Gunderson LL, Jessup JM. Chemoradiotherapy after surgery compared with surgery alone for adenocarcinoma of the stomach or gastroesophageal junction. N Engl J Med. 2001;345:725-730. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2465] [Cited by in RCA: 2435] [Article Influence: 101.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Lee J, Lim do H, Kim S, Park SH, Park JO, Park YS, Lim HY, Choi MG, Sohn TS, Noh JH. Phase III trial comparing capecitabine plus cisplatin versus capecitabine plus cisplatin with concurrent capecitabine radiotherapy in completely resected gastric cancer with D2 lymph node dissection: the ARTIST trial. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:268-273. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 486] [Cited by in RCA: 580] [Article Influence: 41.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Ychou M, Boige V, Pignon JP, Conroy T, Bouché O, Lebreton G, Ducourtieux M, Bedenne L, Fabre JM, Saint-Aubert B. Perioperative chemotherapy compared with surgery alone for resectable gastroesophageal adenocarcinoma: an FNCLCC and FFCD multicenter phase III trial. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:1715-1721. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1216] [Cited by in RCA: 1501] [Article Influence: 107.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Glehen O, Gilly FN, Arvieux C, Cotte E, Boutitie F, Mansvelt B, Bereder JM, Lorimier G, Quenet F, Elias D. Peritoneal carcinomatosis from gastric cancer: a multi-institutional study of 159 patients treated by cytoreductive surgery combined with perioperative intraperitoneal chemotherapy. Ann Surg Oncol. 2010;17:2370-2377. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 320] [Cited by in RCA: 341] [Article Influence: 22.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Rudloff U, Langan RC, Mullinax JE, Beane JD, Steinberg SM, Beresnev T, Webb CC, Walker M, Toomey MA, Schrump D. Impact of maximal cytoreductive surgery plus regional heated intraperitoneal chemotherapy (HIPEC) on outcome of patients with peritoneal carcinomatosis of gastric origin: results of the GYMSSA trial. J Surg Oncol. 2014;110:275-284. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 102] [Cited by in RCA: 169] [Article Influence: 15.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |