Published online Nov 15, 2015. doi: 10.4291/wjgp.v6.i4.120

Peer-review started: May 5, 2015

First decision: May 18, 2015

Revised: June 11, 2015

Accepted: August 25, 2015

Article in press: August 28, 2015

Published online: November 15, 2015

Processing time: 203 Days and 11.7 Hours

Irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) is a common disorder of the gastrointestinal tract with unclear etiology and no reliable biomarker. Like other chronic and functional disorders, medical treatments for IBS are suboptimal and the overall illness burden is high. Patients with IBS report high rates of psychopathology, low quality of life, and increased suicidal ideation. These patients also miss more days of work, are less productive at work, and use many healthcare resources. However, little is known about the burden of IBS on daily functioning. The primary aim of this paper is to review the current literature on the burden of IBS and to highlight the need for further research to evaluate the impact of IBS on daily activities. This research would contribute to our existing understanding of the impact of IBS on overall quality of life and well-being.

Core tip: Little is known about the burden of irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) on daily functioning. The primary aim of this paper is to review the current literature on the overall burden of IBS.

- Citation: Ballou S, Bedell A, Keefer L. Psychosocial impact of irritable bowel syndrome: A brief review. World J Gastrointest Pathophysiol 2015; 6(4): 120-123

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2150-5330/full/v6/i4/120.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4291/wjgp.v6.i4.120

Irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) affects between 10%-15% of the population in North America with a 2:1 ratio of women to men[1,2]. It is classified as a functional gastrointestinal disorder, meaning that its symptoms are not associated with any structural or biochemical abnormalities in the gut. Symptoms of IBS are characterized by abdominal pain and/or discomfort associated with diarrhea, constipation, or a mixture of both[3].

Although there are not currently any biological markers for IBS, recent research has identified physiological factors that contribute to the expression of IBS symptoms. One of the most commonly studied features of IBS is known as the brain-gut axis, which refers to neural and hormonal signaling between the central nervous system and the gastrointestinal tract. In the past decade, the pathophysiology of IBS has been attributed to dysregulation of the brain-gut axis primarily through a process known as visceral hypersensitivity (amplified pain signals originating in the neurons of the gut). In IBS patients, visceral hypersensitivity is believed to cause increased pain and stress symptoms in response to normal bowel activity, resulting in lower thresholds for colonic discomfort when compared to healthy controls[4,5].

Current medical treatments for IBS are relatively ineffective and do not address visceral hypersensitivity. Most available treatments are targeted at reducing specific IBS symptoms, especially symptoms associated with abnormal gut motility. These include laxatives, anti-diarrheals, probiotics, antidepressants, and psychological interventions to enhance stress-management skills and to help patients cope with distress related to symptom experience[6,7]. The best and longest lasting treatment results for IBS have been found in a combination of medical and psychological interventions[8].

The overall burden of IBS is affected in part by high comorbidity of other medical and psychological disorders. Approximately 65% of patients with IBS have comorbid extra-intestinal symptoms and disorders[9] such as fibromyalgia[10], back pain[11], urogenital problems[12], sleep problems[13]. Additionally, 40%-60% of IBS patients (compared to 20% of the overall population) report comorbid psychiatric diagnoses such as anxiety disorders, depression, and Post Traumatic Stress Disorder[14,15]. Patients with IBS are also more likely to report low quality of life[16] and up to 38% of IBS patients in tertiary care settings have contemplated suicide as a result of their symptoms[17].

Given the high psychiatric comorbidity and increased stress-reactivity associated with IBS, several psychological interventions have been tailored to specifically target psychosocial skills deficits in IBS patients. Cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) is the most commonly used and most widely researched psychological treatment for IBS to date. In this treatment, patients are taught to evaluate the relationships between thoughts, behaviors, and emotions and to cope with stressors by learning to modify maladaptive behaviors and to reframe unhelpful cognitions with the goal of improving mood and decreasing stress-reactivity. By doing so, patients can learn to decrease autonomic arousal, which may eventually decrease visceral hypersensitivity and reduce IBS symptoms[18,19]. Newer adaptations of the CBT model have also begun to incorporate data that supports the role of brain-gut dysregulation and symptom-specific processes (i.e., symptom-specific anxiety) in the onset and maintenance of IBS[20,21]. These studies have supported the effectiveness of CBT in treating both physiological and psychological symptoms associated with IBS. For example, in a research study evaluating the effectiveness of 2 different types of CBT compared to Wait List Control, Lackner et al[21] demonstrated that 61%-72% of patients who received CBT treatment reported adequate relief of symptoms compared to 7.4% of Wait List Control patients.

Due to currently insufficient medical interventions for IBS, the burden of living with IBS is quite high. As mentioned above, research has established that patients with IBS have high rates of psychopathology, low quality of life, and increased suicidal ideation. In addition, these patients miss more days of work, are less productive at work, and use many healthcare resources.

The primary goal of psychological interventions for IBS is to ease the overall burden of the illness. Decades of research using psychological parameters have provided a clear understanding of the psychological burden associated with IBS. As mentioned above, approximately 40%-60% of IBS patients have comorbid psychiatric diagnoses[14] and 38% contemplate suicide as a result of their symptoms[17]. Furthermore, these patients report lower quality of life than other patients with serious conditions such as end-stage renal disease or diabetes mellitus[16]. Research studies evaluating the psychological burden of IBS typically rely on validated self-report quality of life measures to evaluate the impact of glycemicindex symptoms of overall well-being[16]. These measures evaluate emotional and physical functioning together, without providing a clear or specific picture of the impact of IBS on daily activities.

A separate body of research has evaluated the burden of IBS on work-productivity and health care utilization[22,23]. This research reveals increased levels of both absenteeism and presenteeism in the workplace when compared to healthy controls. One study estimates that, assuming an IBS prevalence rate of 10%, an employer with 10000 employees could lose $7737600 per year in lost work-productivity due to IBS[22]. Furthermore, IBS accounts for 1.5-2.7 million physician visits a year, frequently resulting in unnecessary, expensive, and invasive diagnostics[24]. For example, 18%-33% of women with IBS have had a hysterectomy, compared to 12% to 17% of women without IBS who have had this same surgery[25,26].

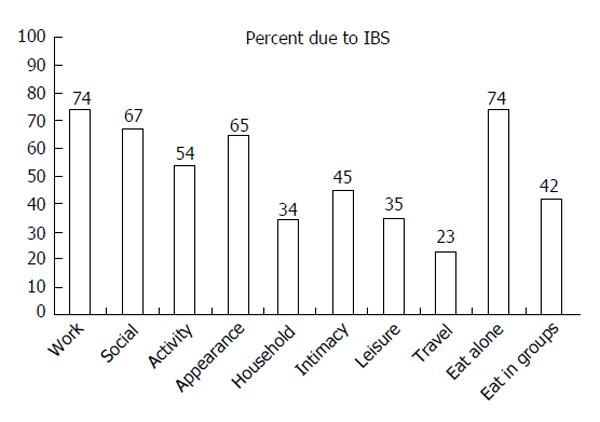

While many studies have evaluated the costly effects of IBS on psychological functioning, healthcare utilization, and work productivity, relatively few studies have focused on overall daily functioning in patients with IBS. Survey studies have shown that IBS patients report higher levels of difficulty in a broad range of daily activities when compared to healthy controls[27]; that IBS negatively affects both mental and physical functioning[16]; and that the reported effect of IBS on daily living is almost as high as that of the flu[28]. Activities that appear to be particularly impaired by IBS include: Work, intimacy, leisure activities, personal relationships, and eating habits[1,28,29]. However, these findings typically come from large survey studies and only one study to our knowledge has sought to quantify functional impairment among IBS patients[29]. The findings from that study suggested high levels of avoidance in a range of daily activities, particularly when symptoms were present.

The existing body of research on the impact of IBS on daily activities has only just begun to address the issue of the burden of IBS on daily functioning. Although most clinicians who work with IBS would agree that many of their patients modify or limit certain activities due to IBS symptoms (or fear of symptoms), this has not been adequately measured or quantified in this population.

Existing studies on functional impairment in IBS have offered, but not evaluated, two possible hypotheses for impaired daily functioning in IBS patients: (1) IBS symptoms may directly impact activities of daily living; and (2) emotional distress and/or maladaptive coping skills may primarily disrupt daily functioning. These hypotheses are consistent with current research in chronic pain suggesting that daily functioning is influenced by both emotional distress and actual physical pain symptoms[30]. To our knowledge, no research study has systematically evaluated the impact of both symptom severity and emotional distress on daily functioning in IBS patients.

A preliminary evaluation of functional impairment in a small sample (n = 35) of women with IBS suggests that patients avoid or are unable to participate in a wide range of activities, which they attribute to IBS symptoms (Figure 1). Interestingly, this preliminary data revealed that although most participants attributed functional impairment to IBS, symptom severity was not a significant predictor of functional impairment. In fact, symptom-specific anxiety and depression were the only significant predictors of impairment in a regression model that included symptom-specific anxiety, psychological distress, and symptom severity[31]. These findings are in-line with literature in pain and anxiety disorders suggesting that functional impairment may be independent of symptom severity. However, further research is required to evaluate the pathways that may lead to functional impairment.

Although the psychosocial and economic burden of IBS has been well documented, further research is necessary to evaluate the impact of IBS on daily activities. As mentioned above, existing measures of quality of life evaluate emotional and physical functioning together and do not provide a clear or specific understanding of the behavioral consequences of IBS (e.g., avoiding social activities, avoiding work, avoiding travel, etc.). Existing research has alluded to behavioral avoidance or inability to participate in daily activities[27-30] but this concept has not yet been adequately or systematically characterized in IBS patients. Further research should evaluate and characterize functional impairment in IBS.

P- Reviewer: Chiarioni G, Ierardi E S- Editor: Ma YJ L- Editor: A E- Editor: Liu SQ

| 1. | Hungin AP, Chang L, Locke GR, Dennis EH, Barghout V. Irritable bowel syndrome in the United States: prevalence, symptom patterns and impact. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2005;21:1365-1375. [PubMed] |

| 2. | Thompson WG, Irvine EJ, Pare P, Ferrazzi S, Rance L. Functional gastrointestinal disorders in Canada: first population-based survey using Rome II criteria with suggestions for improving the questionnaire. Dig Dis Sci. 2002;47:225-235. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 228] [Cited by in RCA: 214] [Article Influence: 9.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Longstreth GF, Thompson WG, Chey WD, Houghton LA, Mearin F, Spiller RC. Functional bowel disorders. Gastroenterology. 2006;130:1480-1491. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3413] [Cited by in RCA: 3383] [Article Influence: 178.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 4. | Fukudo S, Nomura T, Muranaka M, Taguchi F. Brain-gut response to stress and cholinergic stimulation in irritable bowel syndrome. A preliminary study. J Clin Gastroenterol. 1993;17:133-141. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 82] [Cited by in RCA: 83] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Schmulson M, Chang L, Naliboff B, Lee OY, Mayer EA. Correlation of symptom criteria with perception thresholds during rectosigmoid distension in irritable bowel syndrome patients. Am J Gastroenterol. 2000;95:152-156. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 49] [Cited by in RCA: 52] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Lesbros-Pantoflickova D, Michetti P, Fried M, Beglinger C, Blum AL. Meta-analysis: The treatment of irritable bowel syndrome. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2004;20:1253-1269. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 136] [Cited by in RCA: 127] [Article Influence: 6.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 7. | Tillisch K, Chang L. Diagnosis and treatment of irritable bowel syndrome: state of the art. Curr Gastroenterol Rep. 2005;7:249-256. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Mahvi-Shirazi M, Fathi-Ashtiani A, Rasoolzade-Tabatabaei SK, Amini M. Irritable bowel syndrome treatment: cognitive behavioral therapy versus medical treatment. Arch Med Sci. 2012;8:123-129. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Riedl A, Schmidtmann M, Stengel A, Goebel M, Wisser AS, Klapp BF, Mönnikes H. Somatic comorbidities of irritable bowel syndrome: a systematic analysis. J Psychosom Res. 2008;64:573-582. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 178] [Cited by in RCA: 183] [Article Influence: 10.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Sperber AD, Atzmon Y, Neumann L, Weisberg I, Shalit Y, Abu-Shakrah M, Fich A, Buskila D. Fibromyalgia in the irritable bowel syndrome: studies of prevalence and clinical implications. Am J Gastroenterol. 1999;94:3541-3546. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 139] [Cited by in RCA: 152] [Article Influence: 5.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Smith MD, Russell A, Hodges PW. How common is back pain in women with gastrointestinal problems? Clin J Pain. 2008;24:199-203. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Guo YJ, Ho CH, Chen SC, Yang SS, Chiu HM, Huang KH. Lower urinary tract symptoms in women with irritable bowel syndrome. Int J Urol. 2010;17:175-181. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Elsenbruch S, Harnish MJ, Orr WC. Subjective and objective sleep quality in irritable bowel syndrome. Am J Gastroenterol. 1999;94:2447-2452. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 67] [Cited by in RCA: 65] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Drossman DA, Camilleri M, Mayer EA, Whitehead WE. AGA technical review on irritable bowel syndrome. Gastroenterology. 2002;123:2108-2131. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Cohen H, Jotkowitz A, Buskila D, Pelles-Avraham S, Kaplan Z, Neumann L, Sperber AD. Post-traumatic stress disorder and other co-morbidities in a sample population of patients with irritable bowel syndrome. Eur J Intern Med. 2006;17:567-571. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Koloski NA, Talley NJ, Boyce PM. The impact of functional gastrointestinal disorders on quality of life. Am J Gastroenterol. 2000;95:67-71. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 153] [Cited by in RCA: 156] [Article Influence: 6.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Miller V, Hopkins L, Whorwell PJ. Suicidal ideation in patients with irritable bowel syndrome. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2004;2:1064-1068. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 80] [Cited by in RCA: 78] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | van Dulmen AM, Fennis JF, Bleijenberg G. Cognitive-behavioral group therapy for irritable bowel syndrome: effects and long-term follow-up. Psychosom Med. 1996;58:508-514. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 85] [Cited by in RCA: 65] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Weiner H. Some unexplored regions of psychosomatic medicine. Psychother Psychosom. 1987;47:153-159. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Boyce PM, Talley NJ, Balaam B, Koloski NA, Truman G. A randomized controlled trial of cognitive behavior therapy, relaxation training, and routine clinical care for the irritable bowel syndrome. Am J Gastroenterol. 2003;98:2209-2218. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 89] [Cited by in RCA: 88] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Lackner JM, Keefer L, Jaccard J, Firth R, Brenner D, Bratten J, Dunlap LJ, Ma C, Byroads M. The Irritable Bowel Syndrome Outcome Study (IBSOS): rationale and design of a randomized, placebo-controlled trial with 12 month follow up of self- versus clinician-administered CBT for moderate to severe irritable bowel syndrome. Contemp Clin Trials. 2012;33:1293-1310. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Dean BB, Aguilar D, Barghout V, Kahler KH, Frech F, Groves D, Ofman JJ. Impairment in work productivity and health-related quality of life in patients with IBS. Am J Manag Care. 2005;11:S17-S26. [PubMed] |

| 23. | Paré P, Gray J, Lam S, Balshaw R, Khorasheh S, Barbeau M, Kelly S, McBurney CR. Health-related quality of life, work productivity, and health care resource utilization of subjects with irritable bowel syndrome: baseline results from LOGIC (Longitudinal Outcomes Study of Gastrointestinal Symptoms in Canada), a naturalistic study. Clin Ther. 2006;28:1726-1735; discussion 1710-1711. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 130] [Cited by in RCA: 149] [Article Influence: 7.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Shih YC, Barghout VE, Sandler RS, Jhingran P, Sasane M, Cook S, Gibbons DC, Halpern M. Resource utilization associated with irritable bowel syndrome in the United States 1987-1997. Dig Dis Sci. 2002;47:1705-1715. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Hasler WL, Schoenfeld P. Systematic review: Abdominal and pelvic surgery in patients with irritable bowel syndrome. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2003;17:997-1005. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 49] [Cited by in RCA: 52] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Longstreth GF, Yao JF. Irritable bowel syndrome and surgery: a multivariable analysis. Gastroenterology. 2004;126:1665-1673. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 163] [Cited by in RCA: 155] [Article Influence: 7.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Hungin AP, Whorwell PJ, Tack J, Mearin F. The prevalence, patterns and impact of irritable bowel syndrome: an international survey of 40,000 subjects. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2003;17:643-650. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 537] [Cited by in RCA: 526] [Article Influence: 23.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Dapoigny M, Bellanger J, Bonaz B, Bruley des Varannes S, Bueno L, Coffin B, Ducrotté P, Flourié B, Lémann M, Lepicard A. Irritable bowel syndrome in France: a common, debilitating and costly disorder. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2004;16:995-1001. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 65] [Cited by in RCA: 61] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Corney RH, Stanton R. Physical symptom severity, psychological and social dysfunction in a series of outpatients with irritable bowel syndrome. J Psychosom Res. 1990;34:483-491. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 112] [Cited by in RCA: 115] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Bass C. The role of emotion in determining pain. Dig Dis. 2009;27 Suppl 1:16-23. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |