OVERT (ACUTE) GI BLEEDING

Epidemiology

Acute GI bleeding is a major cause of hospital admissions in the United States, which is estimated at 300000 patients annually[15]. Upper GI bleeding has an annual incidence that ranges from 40-150 episodes per 100000 persons and a morality rate of 6%-10%[16-18]; compared with lower GI bleeding which has an annual incidence ranging from 20-27 episodes per 100000 persons and a mortality rate of 4%-10%[19,20]. Acute GI bleeding is more common in men than women and its prevalence increases with age[13,21].

Etiology and pathophysiology

Acute upper GI bleeding may originate in the esophagus, stomach, and duodenum. Upper GI bleeding can be categorized based upon anatomic and pathophysiologic factors: ulcerative, vascular, traumatic, iatrogenic, tumors, portal hypertension. The commonest causes of acute upper GI bleeding are peptic ulcer disease including from the use of aspirin and other non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), variceal hemorrhage, Mallory-Weiss tear and neoplasms including gastric cancers[8]. Other relatively common causes include esophagitis, erosive gastritis/duodenitis, vascular ectasias and Dieulafoy’s lesions[22]. Significant geographical variations in pathophysiology exist for esophageal varices and peptic ulceration between the East and the West, with East Asians having a stronger association with non-alcoholic cirrhosis and helicobacter pylori as their respective etiologies which generally have a more favorable prognosis[23,24]. However, esophageal varices and peptic ulcer disease are nevertheless major causes of upper GI bleeding in both Eastern and Western societies[24,25].

Acute lower GI bleeding may originate in the small bowel, colon or rectum[21]. The causes of acute lower GI bleeding may also be grouped into categories based on the pathophysiology: vascular, inflammatory, neoplastic, traumatic and iatrogenic. Common causes of lower GI bleeding are diverticular disease, angiodysplasia or angiectasia, neoplasms including colorectal cancer, colitis including Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis, and benign anorectal lesions such as hemorrhoids, anal fissures and rectal ulcers[8].

In the special setting where the patient is known to have an abdominal aortic aneurysm or an aortic graft, acute GI bleeding should be considered secondary to aortoenteric fistula until proven otherwise[26].

Initial evaluation

Rapid assessment and resuscitation should precede diagnostic evaluation in unstable patients with acute severe bleeding[27]. Once hemodynamic stability is assured, patients should be evaluated for the immediate risk of rebleeding and complications, as well as the underlying source of bleeding. For acute upper GI bleeding, risk scores such as the Rockall Score and Glasgow Blatchford Score (GBS) have been developed and validated[6,28]. Patients with minimal or intermittent bleeding who are stratified as low risk can be evaluated in an outpatient setting, allowing more effective utilization of limited hospital in-patient resources[19]. While the Rockall score uses endoscopic findings, the GBS is based upon the patient’s clinical presentation such as systolic blood pressure, pulse, presence of melena, syncope, hepatic disease, cardiac failure and laboratory parameters such as blood urea nitrogen and hemoglobin. A meta-analysis found that a GBS of zero decreases the likelihood of requiring urgent intervention (likelihood ratio 0.02, 95%CI: 0-0.05)[4]. Therefore, the GBS may be best suited for initial risk evaluation of suspected acute upper GI bleeding, such as in the emergency department setting.

As in the diagnosis of any disease, the clinical history, physical examination and initial laboratory findings are crucial in determining the likely sources of bleeding which would help direct the appropriate definitive investigation and intervention. A medication history here is particularly important, especially on the use of aspirin and other NSAIDs.

Clinical presentation

Upper GI bleeding usually presents with hematemesis (vomiting of fresh blood), “coffee-ground” emesis (vomiting of dark altered blood), and/or melena (black tarry stools). Hematochezia (passing of red blood from rectum) usually indicates bleeding from the lower GI tract, but can occasionally be the presentation for a briskly bleeding upper GI source[9]. The presence of frank bloody emesis suggests more active and severe bleeding in comparison to coffee-ground emesis[29]. Variceal hemorrhage is life threatening and should be a major consideration in diagnosis as it accounts for up to 30% of all cases of acute upper GI bleeding and up to 90% in patients with liver cirrhosis[30].

Lower GI bleeding classically presents with hematochezia, however bleeding from the right colon or the small intestine can present with melena[31]. Bleeding from the left side of the colon tends to present bright red in color, whereas bleeding from the right side of the colon often appears dark or maroon-colored and may be mixed with stool[31].

Other presentations which can accompany both upper and lower GI bleeding include hemodynamic instability, abdominal pain and symptoms of anemia such as lethargy, fatigue, syncope and angina[21]. Patients with acute bleeding usually have normocytic red blood cells. Microcytic red blood cells or iron deficiency anemia suggests chronic bleeding. In contrast to patients with acute upper GI bleeding, patients with acute lower GI bleeding and normal renal perfusion usually have a normal blood urea nitrogen-to-creatinine or urea-to-creatinine ratio[32]. In general, anatomic and vascular causes of bleeding present with painless, large-volume blood loss, whereas inflammatory causes of bleeding are associated with diarrhoea and abdominal pain[33].

When patients with known abdominal aortic aneurysm or aortic graft present with above symptoms of GI bleeding, aortoenteric fistula most commonly at the duodenum should be strongly suspected. In this case, urgent computed tomography (CT) abdomen or CT angiogram is indicated to look for loss of tissue plane between the aorta and duodenum, contrast extravasation and the presence of gas indicating graft infection. Upper endoscopy prior to surgical intervention may help exclude other diagnoses when CT findings are not definitive[26,34]. The details of these investigations are discussed later in this review.

Investigations

Options for the investigation of acute GI bleeding include upper endoscopy and/or colonoscopy, nuclear scintigraphy, CT angiogram and catheter angiography. The investigation of choice would be guided by the suspected location of bleeding (upper vs lower GI) based on clinical presentation. In most circumstances, the standard of care for the initial diagnostic evaluation of suspected acute GI bleeding is urgent upper endoscopy and/or colonoscopy, as recommended by guidelines from the American College of Gastroenterology and the 2010 International Consensus Recommendations[20,27]. As investigations are being planned, infusions of proton pump inhibitor or octreotide should be initiated for suspected bleeding peptic ulcer and varices respectively[27,30].

Upper endoscopy

In patients with acute upper GI bleeding, upper endoscopy is considered the investigation of choice[35]. Early upper endoscopy within 24 h of presentation is recommended in most patients with acute upper GI bleeding to confirm diagnosis and has the benefit of targeted endoscopic treatment (Figure 1), resulting in reduced morbidity, hospital length of stay, risk of recurrent bleeding and the need for surgery[27]. Endoscopic evacuation of hematoma or blood clot may enable visualization of underlying pathology such as a visible vessel in a peptic ulcer and allows directed endoscopic hemostatic therapy[36,37]. The reported sensitivity and specificity of endoscopy for upper gastroduodenal bleeding are 92%-98% and 30%-100%, respectively[38]. Risks of upper endoscopy include aspiration, side-effects from sedation, perforation, and increased bleeding while attempting therapeutic intervention. The airway should be secured by endotracheal intubation in the case of massive upper GI bleeding.

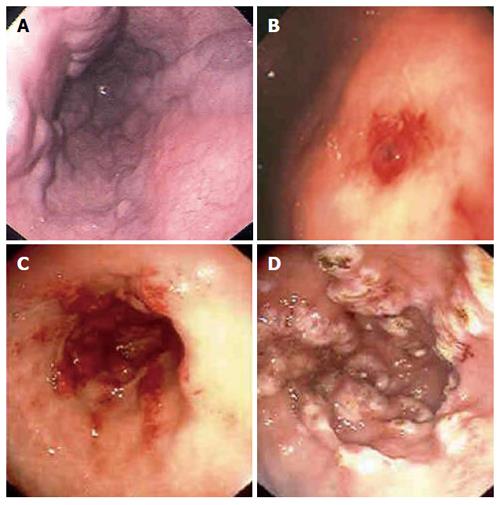

Figure 1 Upper endoscopic findings in patients with suspected upper gastrointestinal bleeding.

Esophageal varices (A), Dieulafoy’s lesion in the stomach (B), gastric antral vascular ectasia (watermelon stomach) in the antrum of the stomach pre and post argon plasma coagulation therapy (C, D).

The use of nasogastric-tube insertion and gastric lavage in all patients with suspected upper GI bleeding is controversial and studies have failed to demonstrate a benefit in clinical outcomes[39,40]. The use of prokinetics such as erythromycin and metoclopramide as a single dose before upper endoscopy promotes gastric emptying and clearance of blood, clots and food. Two meta-analyses have demonstrated the use of a prokinetic agent improved visibility at endoscopy and significantly reduced the need for repeat endoscopy[41,42]. In particular, the use of erythromycin was associated with a decrease in the amount of blood in the stomach, reduced amount of blood transfusion and shorter length of hospital stay[42]. Therefore prokinetics such as erythromycin before upper endoscopy should be recommended for patients with major bleeding who are expected to have large amount of blood in the stomach.

The practice of routine second look endoscopy after hemostasis is achieved on first endoscopy remains controversial. Two meta-analyses of randomized controlled trials have shown that second look endoscopy significantly reduced peptic ulcer rebleeding but did not improve overall mortality[43,44]. Due to the relatively small number of subjects studied, suboptimal hemostatic measures used and the lack of proton pump inhibitor use in those trials, the 2010 International Consensus Recommendations did not recommend routine use of second look endoscopy but stated it may be useful in selected patients with high risk of re-bleeding[27]. This should be considered particularly when there are concerns of suboptimal prior endoscopy and potential missed lesions.

In cases of acute upper GI bleeding where upper endoscopy is non-diagnostic in which a bleeding site cannot be identified or treated, the next investigation depends on the patient’s hemodynamic stability. If the patient is unstable with large volume upper GI blood loss, patient should proceed to urgent surgery, such as an exploration and partial gastrectomy for uncontrolled bleeding gastric ulcer[9]. Intraoperative endoscopy may be a useful adjunct during surgery to help localize the source of bleeding[45,46]. If the patient is hemodynamically stable with low volume bleeding, repeat endoscopy may be considered. Colonoscopy should also be considered in the setting of melena to exclude a right-sided colonic source of bleeding, as discussed later.

Further imaging should be considered after non-diagnostic upper endoscopy with or without colonoscopy and the options include CT angiography, catheter angiography and nuclear scintigraphy[38], all of which are discussed separately in later sections of this review. Upper GI barium studies are contraindicated in the setting of acute upper GI bleeding because they may interfere with subsequent investigations or surgery[22], and due to the risk of barium peritonitis if there is a pre-existing perforation of the bowel wall[47].

Colonoscopy

In acute lower GI bleeding, the diagnostic approach is somewhat more variable. Colonoscopy and CT angiogram are the two diagnostic tools of choice for evaluation of acute lower GI bleeding[15]. The American College of Gastroenterology guidelines suggest that colonoscopy should be the first-line diagnostic modality for evaluation and treatment of lower GI bleeding[20]. Studies have indicated that colonoscopy identifies definitive bleeding sites (Figure 2) in 45%-90% of patients[48]. Advantages of colonoscopy include direct visualization, access to tissue biopsy and endoscopic hemostatic therapy, and as an initial diagnostic test has a higher sensitivity[15,49]. However, there are several limitations to colonoscopy in the setting of acute lower GI bleeding, including potential inadequate bowel preparation, the inability to evaluate most of the small bowel, as well as risks associated with sedation, perforation and bleeding similar to upper endoscopy[50]. In patients with inadequate bowel preparation, the sensitivity drops significantly and successful treatment may only be possible in as few as 21% of patients in the acute setting[51]. It has been advocated that urgent colonoscopy in this setting should be preceded by a rapid purge with isotonic colonic lavage 4-6 liters orally until the effluent passed is diluted pink in color. This rapid purge may require the use of a nasogastric tube and a prokinetic agent such as metoclopramide. This is based on the findings that blood or stool in the colon can obscure the bleeding source during urgent colonoscopy[51,52].

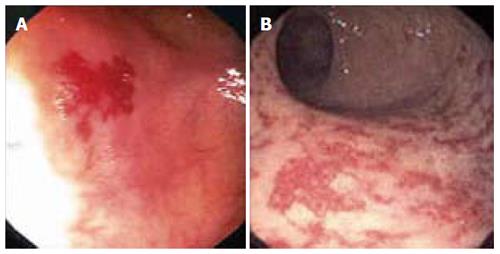

Figure 2 Colonoscopic findings in patients with suspected lower gastrointestinal bleeding.

Colonic angiodysplasia (A) and radiation proctopathy (B).

It is recommended by the American College of Radiology that colonoscopy be utilized as the initial modality in hemodynamically stable patients (allowing for adequate bowel preparation) and angiography in those are who are hemodynamically unstable with massive lower GI bleeding[53]. It should be noted that colonoscopy is also indicated in the evaluation of patients presenting with melena who have negative upper endoscopy to exclude a right-sided colonic source of bleeding.

In cases where the source of bleeding is unidentified after upper endoscopy and/or colonoscopy, the utilization of subsequent diagnostic modalities should be guided by clinical presentation, hemodynamic stability and local expertise with the individual tests. No large randomized trials have demonstrated superiority of a particular strategy. The next section will outline the diagnostic use of CT angiography, catheter angiography and radionuclide imaging in acute GI bleeding.

CT angiography

CT angiography requires the rate of ongoing arterial bleeding to be at least 0.5 mL/min to reliably show extravasation of contrast into the bowel lumen to identify a bleeding site[54]. A systematic review of the diagnostic accuracy of CT angiography demonstrated a sensitivity of 86% and specificity of 95% in the evaluation of patients with acute GI bleeding[55]. The potential advantages of CT angiogram in diagnosis of acute GI bleeding include its minimally invasive nature and its wider availability in comparison to catheter angiography[38]. It can also demonstrate neoplasms or vascular malformations and provide evidence of recent bleeding, such as hyperdense blood in bowel lumen[38,56]. Active GI bleeding is diagnosed by extravasation of contrast into the bowel lumen, which appears as an area of high attenuation on the arterial phase scan which increases on the venous phase scan (Figure 3A-D). By demonstrating the precise site of bleeding and the underlying etiology, CT angiography is useful for directing and planning definitive treatment whether it be through endoscopy, catheter angiography or surgery[57]. If the gastrointestinal bleeding is intermittent and the initial CT is negative, a repeat CT angiogram can be performed when rebleeding occurs[58].

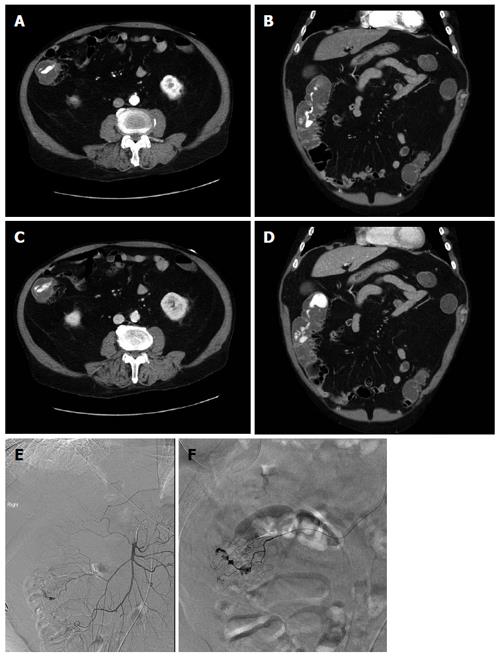

Figure 3 73-year-old man with per rectal bleeding and active gastrointestinal hemorrhage.

Contrast enhanced computed tomography (CT) angiogram images show extravasation of contrast into the lumen of the ascending colon, with pooling of contrast which increases from the arterial phase (A, B) to the delayed venous phase (C, D). Diverticula are seen arising from the medial wall of the ascending colon indicating the etiology of bleeding. Following the CT angiogram, the patient underwent catheter angiography, which demonstrated blush of contrast from the right colic branch of the superior mesenteric artery (E). Selective catheterization of the right colic artery demonstrates the bleeding focus more clearly (F). Gelfoam and coil embolization was subsequently performed.

Disadvantages of CT angiography is the lack of therapeutic capability, risk of contrast induced nephropathy in patients with renal impairment and contrast allergy[59]. It has been suggested that the role of CT angiography in evaluation of patients with acute GI bleeding is in those who are stable and when upper endoscopy or colonoscopy is unable to locate the site of bleeding. Patients with massive GI hemorrhage with hemodynamic instability are recommended to proceed directly to catheter angiography or urgent surgery[38].

Catheter angiography

Catheter angiography can detect bleeding at rates of 0.5 to 1.5 mL/min[60,61]. It is used often in suspected acute lower GI bleeding due to anatomical availability of end arteries and is more challenging in acute upper GI bleeding due to the presence of multiple collateral vessels[62]. In comparison to other imaging modalities it offers the advantages of being both a diagnostic and therapeutic tool allowing for infusion of vasoconstrictive drugs and/or embolization (Figure 3E and F). It also does not require bowel preparation. The sensitivity for a diagnosis of acute GI bleeding is 42%-86% with the specificity close to 100%[63]. Other factors that may affect the sensitivity of angiography include intermittent bleeding, procedural delays, atherosclerotic anatomy, and venous or small vessel bleeding[64,65].

Complications include access-site hematoma or pseudoaneurysm, arterial dissection or spasm, bowel ischemia, and contrast-induced nephropathy or allergic reaction. Complications occur in 0%-10% of patients undergoing angiography, with the incidence of serious complications occurring in < 2% of patients[48,66]. It is recommended that catheter angiography be reserved for patients in whom endoscopy is not feasible due to severe bleeding with hemodynamic instability, or in those with persistent or recurrent GI bleeding and a non-diagnostic upper endoscopy and/or colonoscopy[20].

Radionuclide imaging

The threshold rate of GI bleeding for localization with radionuclide scanning is 0.1 mL/min, and this is the most sensitive imaging modality for GI bleeding[67]. Nuclear scans are either technetium-99m (99mTc) sulphur colloid or 99mTc pertechnetate-labelled autologous red blood cells. The short half-life of 99mTc sulphur colloid is a limitation as this means that patients must be actively bleeding during the few minutes the label is present in the intravascular space, and repeat scanning for intermittent bleeding is not possible without reinjection. 99mTc pertechnetate-labelled red blood cell scan allows for frequent abdominal images up to 24 h if necessary and is more commonly utilized for investigation of patients with obscure, intermittent bleeding. The main disadvantage of this test is poor anatomic localization of the bleeding site, and this poorly predicts subsequent angiogram results[68,69]. Furthermore, radionuclide only provides functional data, and is unable to diagnose the pathological cause of GI bleeding. Although advocated as a guide for surgical resection, surgical planning should not be based on only a positive nuclear scan[70].

All imaging studies have the advantage of allowing the clinician to identify the location of bleeding throughout the GI tract, especially those originating from the small bowel. However, their use is often limited by the need for active bleeding at the time of investigation. Other diagnostic modalities such as push enteroscopy, deep small bowel enteroscopy and capsule endoscopy may be of value when the above described investigations prove to be non-diagnostic and when patients are hemodynamically stable with low volume bleeding. These studies will be discussed in the subsequent section evaluating chronic occult GI bleeding.

OCCULT (CHRONIC) GI BLEEDING

Epidemiology

Chronic occult GI bleeding occurs in the setting of a positive FOBT and/or iron deficiency anemia. Iron deficiency is the most common cause of anemia worldwide. In developed countries the major cause of iron deficiency is secondary to chronic blood loss[71]. In the United States, it is estimated that 5%-11% of women and 1%-4% of men are iron deficient and 5% and 2% of adult women and men have iron deficiency anemia, respectively[72]. Iron deficiency anemia has traditionally been attributed to chronic occult GI bleeding, especially in groups other than premenopausal women, and warrants further investigation of the gastrointestinal tract, including for colorectal cancer[12].

Etiology and pathophysiology

Chronic occult GI bleeding may occur anywhere in the GI tract, from the oral cavity to the anorectum[73]. In a systematic review of five prospective studies, 29%-56% of patients had an upper GI source and 20%-30% of patients had a colorectal source of occult GI bleeding diagnosed by the means of upper endoscopy and colonoscopy. These studies were unable to identify a source in 29%-52% of patients[74]. Causes of chronic occult GI bleeding can be broadly categorized into mass lesions, inflammatory, vascular, and infectious[12]. More common causes include colorectal cancer (especially right-sided colon), severe esophagitis, gastric or duodenal ulcers including from the use of aspirin and other NSAIDs, inflammatory bowel disease, gastric cancer, celiac disease, vascular ectasias (any site), diverticula, and portal hypertensive gastropathy. Non-GI sources of blood loss such as hemoptysis and oropharyngeal bleeding can also cause a positive FOBT[75]. A small bowel source accounts for a high percentage of patients with chronic occult GI bleeding and negative findings on upper endoscopy and colonoscopy[10], which is classified as obscure GI bleeding.

Clinical presentation

Patients with iron deficiency anemia may or may not be symptomatic. Rockey[75] recommended that initial investigation be directed towards the location of specific symptoms if possible. In the absence of symptoms, particularly in the elderly, the colon should be evaluated first, and if this is negative, upper GI tract is further investigated[75]. A targeted history is of value to discern symptoms of unintentional weight loss (suggestive of malignancy), use of aspirin or other NSAIDs (ulcerative mucosal injury), antiplatelet or anticoagulant use, family history, liver disease, and previous gastrointestinal tract surgery[76]. Physical signs could indicate presence of an underlying condition such as celiac disease, inflammatory bowel disease, Plummer-Vinson syndrome, and Peutz-Jeghers syndrome[74].

Investigations

Once a patient has been identified as having positive FOBT and/or iron deficiency anemia, multiple diagnostic procedures are available for investigation of the GI tract. The choice and sequence of procedures will depend on clinical suspicion and symptoms[10]. Endoscopic measures include upper endoscopy, colonoscopy, deep enteroscopy, or capsule endoscopy. CT colonography, CT and magnetic resonance (MR) enterography are some of the radiographic investigations utilized in the evaluation of patients with chronic occult GI bleeding. The role of barium enema, small bowel series, enteroclysis, standard CT or MR imaging and nuclear scans have substantially declined due to their low diagnostic yield and the advent of capsule endoscopy[11]. The choice of investigation should also incorporate consideration of patient risk factors and preference. In general, colonoscopy and upper endoscopy are the initial investigations of choice for chronic occult GI bleeding[11].

Colonoscopy and upper endoscopy

The 2007 American Gastroenterological Association guidelines on obscure GI bleeding recommended that the evaluation of a patient with a positive FOBT depends upon whether iron deficiency anemia is present. Patients with positive FOBT and no anemia should first be investigated with a colonoscopy (if upper GI symptoms present then also upper endoscopy) whereas patients with iron deficiency anemia should undergo both upper endoscopy and colonoscopy[11]. Patients with negative findings on upper endoscopy and colonoscopy without anemia do not require further investigations, but those with anemia should be referred for further investigation of the small bowel. The initial small bowel investigation of choice, when available, is wireless capsule endoscopy[11].

Capsule endoscopy, push enteroscopy and deep enteroscopy

Wireless capsule endoscopy is a simple, non-invasive method to study the small intestine for evaluation of small intestinal occult GI bleeding (Figure 4). The diagnostic yield in patients with chronic occult and obscure GI bleeding (after negative upper endoscopy and colonoscopy) ranges from 55%-92% for capsule endoscopy[77,78] in comparison to 25%-30% for push endoscopy[79,80]. A meta-analysis of 14 studies demonstrated that the diagnostic yield of capsule endoscopy was superior to push enteroscopy (63% vs 28%) and barium studies (42% vs 6%)[81]. Capsule endoscopy also avoids the higher rates of morbidity and mortality associated with push enteroscopy[82]. Capsule endoscopy is less useful in evaluating colonic sources of bleeding because of retained stool, battery life and poor field of vision due to the colon’s large diameter[48]. Complications related to the procedure are rare and include capsule retention and obstruction[83].

Figure 4 Jejunal angiodysplasia as seen on capsule endoscopy.

Push enteroscopy can evaluate the GI tract to 60-80 cm of the proximal jejunum. However, with the availability of deep enteroscopy, which can reach to the distal small bowel, the use of push enteroscopy has diminished. Three systems widely used are: the double balloon endoscopy system, the single balloon enteroscope system, and the Endo-Ease Discovery SB small bowel enteroscope or spiral enteroscope, and may be performed via the oral or anal route[10]. Studies comparing the three different modalities are lacking. The advantage of deep enteroscopy over capsule endoscopy is that it can also be a therapeutic modality. The diagnostic yield of double-balloon enteroscopy varies from 40%-80% and therapeutic success ranging between 15%-55%[84,85].

Radiographic imaging modalities

Historically, an upper GI series with small bowel follow-through and/or enteroclysis was the next test performed, but in recent years, where available, CT and MR enterography have superseded these older radiographic modalities.

CT enterography involves ingestion of a neutral contrast agent to distend the small bowel which enables better evaluation of the small bowel wall in comparison to barium solutions. The alternative is MR enterography which has the advantage of not using ionizing radiation allowing serial imaging of the small bowel.

Compared to capsule endoscopy, CT enterography provides better visualization of the entire small bowel wall and shows extra-enteric complications of small bowel disease, whereas capsule endoscopy allows direct visualization of the small bowel mucosa and has a higher sensitivity for mucosal processes[86].

OBSCURE GI BLEEDING

Obscure GI bleeding accounts for 5% of patients of all cases of GI bleeding, both acute overt and chronic occult[12,76]. It is defined as recurrent bleeding when the source remains unidentified after endoscopic procedures and is most commonly caused by bleeding from the small intestine. The commonest causes of obscure GI bleeding include small bowel tumors, vascular anomalies such as angiodysplasias and varices, diverticula and Celiac disease. The emphasis in diagnosis of obscure GI bleeding is the investigation of the small bowel[76].

Repeat upper endoscopy and/or colonoscopy should be considered as one study using double-balloon enteroscopy showed that 24.3% of obscure GI bleed were of non-small bowel origin and within the reach of conventional upper and lower endoscopes[87]. The already mentioned small bowel investigations using capsule endoscopy and deep enteroscopy techniques (including double-balloon enteroscopy, single-balloon enteroscopy and spiral enteroscopy) have enabled the diagnosis of substantially more cases of obscure GI bleeding. Independent series showed that capsule endoscopy had a diagnostic yield of 53%-68% in obscure GI bleeding, led to a specific intervention in the majority of patients and was associated with a significant reductions in hospitalizations and blood transfusions[88,89]. In a randomized controlled trial in patients with iron deficiency anemia and obscure GI bleeding, capsule endoscopy identified a bleeding source significantly more than push enteroscopy (50% vs 24%, P = 0.02)[90]. Double-balloon enteroscopy was shown in a systematic review to have a diagnostic yield of approximately 68% in obscure GI bleeding[91]. A meta-analysis of studies comparing capsule endoscopy and double-balloon enteroscopy concluded comparable diagnostic yield (60% vs 57%, P = 0.42) in small bowel disease and obscure GI bleeding[92]. Capsule endoscopy has the major advantage of being less invasive than deep enteroscopy but the major advantage of deep enteroscopy techniques is their ability to perform treatment at the same time. The choice between capsule endoscopy and deep enteroscopy should be individualized for each patient and one approach may be initial capsule endoscopy followed by a directed deep enteroscopy as directed intervention[76].

CT or MR enterography may be considered as an alternative investigation for small bowel disease due to its ability to visualize the small bowel wall and extra-enteric complications, especially when capsule endoscopy and deep enteroscopy are non-diagnostic. In patients with signs of active bleeding, the above mentioned technetium-99 radionuclide scan, CT angiography and catheter angiography should be considered to help locate the lesion prior to intervention.