Published online Aug 15, 2014. doi: 10.4291/wjgp.v5.i3.271

Revised: June 1, 2014

Accepted: June 18, 2014

Published online: August 15, 2014

Processing time: 177 Days and 4.2 Hours

Obscure gastrointestinal bleeding is still a clinical challenge for gastroenterologists. The recent development of novel technologies for the diagnosis and treatment of different bleeding causes has allowed a better management of patients, but it also determines the need of a deeper comprehension of pathophysiology and the analysis of local expertise in order to develop a rational management algorithm. Obscure gastrointestinal bleeding can be divided in occult, when a positive occult blood fecal test is the main manifestation, and overt, when external sings of bleeding are visible. In this paper we are going to focus on overt gastrointestinal bleeding, describing the physiopathology of the most usual causes, analyzing the diagnostic procedures available, from the most classical to the novel ones, and establishing a standard algorithm which can be adapted depending on the local expertise or availability. Finally, we will review the main therapeutic options for this complex and not so uncommon clinical problem.

Core tip: This is an invited in depth review of occult gastrointestinal bleeding, addressing its pathophysiology, diagnosis and treatment. Our paper tries to unify in one single manuscript all what a general gastroenterologist should know about those items. From the essentials of pathophysiology, we have tried to build a rational approach to those patients’ management depending on the severity of the condition, proposing an evidence-based management algorithm.

- Citation: Sánchez-Capilla AD, De La Torre-Rubio P, Redondo-Cerezo E. New insights to occult gastrointestinal bleeding: From pathophysiology to therapeutics. World J Gastrointest Pathophysiol 2014; 5(3): 271-283

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2150-5330/full/v5/i3/271.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4291/wjgp.v5.i3.271

Gastrointestinal bleeding is a term that includes any bleeding originating from the esophagus to the anus. Classically, it has been classified in upper or lower depending on the location of the bleeding source, proximal or distal to the angle of Treitz.

The usual management of gastrointestinal bleeding (GIB) involves an upper endoscopy and colonoscopy in a first attempt to find the bleeding lesion. If those are unsuccessful, and there’s a bleeding persistence or recurrence, the entity is called gastrointestinal bleeding of obscure origin or obscure gastrointestinal bleeding (OGIB), being the source of bleeding usually located in the small bowel. This segment of the gastrointestinal tract has been impossible to endoscopic exploration for a long time. It has been studied with suboptimal procedures such as small bowel series or enteroclysis in mild cases, or with more aggressive methods in severe cases, such as intraoperative enteroscopy (IE).

But the development of new endoscopic procedures like wireless capsule endoscopy or therapeutic procedures like the new enteroscopes, with different modalities of overtubes and balloons, has allowed an accurate exploration of this part of the GI tract, modifying significantly OGIB patients’ management.

From 2006 a new OGIB classification has been proposed, based on the segment of the GI tract where the bleeding source is located, which determines the needed procedures for its diagnosis and treatment. Indeed, upper gastrointestinal bleeding is defined as the one with a bleeding source proximal to the ampulla, therefore accessible to upper endoscopy; mid GI bleeding is established when the causative lesion is between the ampulla and the ileocecal valve. Finally, lower GI bleeding has a colorectal bleeding source accessible to colonoscopy[1].

Therefore, obscure OGIB can be defined as a persistent or recurrent GI bleeding without a bleeding source found after performing upper endoscopy and colonoscopy. OGIB comprises 5% of all GI bleeding cases, constituting a diagnostic and a therapeutic challenge, either because of the morbidity and mortality associated, as well as for the high consumption of health resources for its diagnosis and treatment[2].

In most of OGIB patients (75%), the bleeding source is located in the small bowel[3], being normally a mid-GI bleeding[4]. The rest of the lesions are usually in areas accessible to conventional endoscopy, but overlooked in previous endoscopic procedures.

OGIB refers to two different clinical situations, regarding the onset of the GI bleeding: (1) Obscure-occult GI bleeding refers to the patient with a GI bleeding detected by a positive occult blood fecal test, with or without iron depletion; (2) Obscure-overt GI bleeding, in which an evident GI bleeding is seen, in the form of melena or hematochezia[5]. This review addresses the diagnosis and management of patients with obscure-overt GI bleeding, with a special interest in the different available procedures, establishing a management algorithm.

Causes of OGIB include overlooked bleeding lesions by upper endoscopy or colonoscopy, as well as the ones that, after an exhaustive endoscopic study, are classified as mid-GI bleeding[6]. The causative condition of OGIB is highly determined by age, being tumors as lymphoma, carcinoids, and GIST more likely in patients of less than 40 years, and vascular lesions as angiodysplasia more usual in elder patients, comprising 40% of all cases[7]. Table 1 contains the main recognized causes of OGIB[5].

| Overlooked lesions in the upper GI tract or in the colon |

| Upper GI tract (proximal to the angle of Treitz) |

| Cameron ulcers |

| Fundic varices |

| Peptic ulcer |

| Angiectasia |

| Dieulafoy lesion |

| Gastric antral vascular ectasia |

| Colorectal lesions |

| Angiectasia |

| Polyps |

| Neoplasms |

| Anal disease |

| Dieulafoy lesion |

| Mid-GI tract lesions |

| < 40 yr |

| Meckel diverticulum |

| Dieulafoy lesion |

| Tumors (GIST, Lymphoma, Carcinoids, etc.) |

| Inflammatory bowel disease |

| Celiac disease |

| 40-60 yr |

| Small bowel tumors |

| Angiodysplasia |

| Celiac disease |

| NSAID’s related lesions |

| > 60 yr |

| Angiodysplasia |

| Small bowel tumors |

| NSAID’s related lesions |

| Rare causes (< 1%) |

| Haemobilia |

| Aortoenteric fistula |

| Hemosuccus pancreaticus |

Angiodysplasia is one of the most usual causes of over OGIB in patients older than 40 years, and the most frequent cause in patients older than 60 years[7]. They are also known as arteriovenous malformations or vascular ectasia, more frequently found in the stomach, duodenum, cecum and ascending colon. Most of them are acquired but some may be present at birth, or as a part of some hereditary syndromes[8]. Pathogenesis is uncertain and four theories have been proposed: (1) Some attribute angiodysplasia to a mild chronic venous obstruction. This hypothesis is concordant with the observation of a higher number of these lesions in the right colon, where the wall tension is higher; (2) They could be a complication of mucosal chronic ischemia, which could appear in episodes of bowel obstruction or after tough straining when defecating; (3) Some authors think they could be a complication of local ischemia in patients with heart, vascular or lung disease[9]; (4) Some of them, usually in younger patients, could be congenital or associated to hereditary syndromes; (5) It has also been suggested a pathogenic relation between aortic stenosis and angiodysplasia, caused by the haemodinamic abnormalities determined by the valvular disease (Heyde Syndrome)[10]. Therapy is controversial, but some studies have shown a reduction in bleeding episodes after valvular replacement; and (6) In terminal cardiac failure, left ventricular assisted devices have been associated with increased bleeding episodes from angiodysplasia. In these cases, pathogenesis seems related with anticoagulant therapy, vascular malformations, loss of activity of Von Willebrand factor and mucosal ischemia[11].

Despite infrequent, GI bleeding is the usual clinical onset, being more frequent in benign tumors as leyomioma than in malignant lesions as leyomiosarcoma[12]. Bleeding is caused by erosion of the tumor surface or by the rupture of aberrant vascular structures within the lesion.

This is a relevant condition in patients of less than 25 years old. Despite rare, it is the most frequent congenital abnormality in the GI tract. They are caused by the incomplete obliteration of the vitelin duct during embryogenesis, which leads to the formation of a true small bowel diverticulum[13]. Meckel diverticulum has all the bowel wall layers, and in 12%-21% of cases it may contain ectopic tissues (gastric or duodenal mucosa or even pancreatic ducts). They are usually asymptomatic, but may also cause abdominal pain or OGIB. Bleeding is caused by an ulceration of the small bowel due to acid secretion by heterotopic gastric mucosa contained within the diverticular layers. Bleeding can be chronic and insidious, or acute and massive, but transfusion is hardly ever required. The main anatomical risk factor that makes bleeding more likely is diverticula size of more than 2 cm[14].

Etiology is unknown. Lesions are normally found in the proximal stomach, in the lesser curvature, near de esophago-gastric junction. It is usually a submucosal, dilated, aberrant vessel that erodes the overlaying mucosa without a previous ulcer[15]. This is caused by the lack of ramification of the submucosal artery which makes its diameter ten times the normal diameter of a mucosal capillary. Triggering causes are unclear and it usually appears in male patients with comorbidities such as cardiovascular diseases, arterial hypertension, chronic kidney disease, diabetes or alcohol abuse. It is important to mention that this lesion can be overlooked in an endoscopic exam[16], given that quite frequently the aberrant vessel cannot be seen unless it bleeds actively.

GI bleeding is usually associated to complications in both conditions, which can be ulcers or tumors like adenocarcinoma or lymphoma.

At lasts, we would like to emphasize three rare OGIB causes, associated to a high mortality and a difficult diagnosis[17].

Haemobilia: It consists in the bleeding from the biliary tree caused by a communication with vascular structures. The most frequent causes are a closed traumatisms, hepatic artery or portal vein aneurisms, liver abscesses, neoplasms or secondary to procedures such as liver biopsy or bile duct stones extraction[18]. Diagnosis is always difficult[19]. It should be suspected in the anamnesis, when the patient presents upper right quadrant pain, jaundice and OGIB, but this is an unusual form of presentation. Diagnosis can be confirmed by direct endoscopic visualization of blood passing through the papilla. Angiography is a therapeutic option but, despite a successful embolization or surgical treatment of the originating vessel, mortality is high.

Aortoenteric fistula: It is an exceptional but severe cause of OGIB, usually related to a previous aortoiliac surgery. The most common cause of primary aortoenteric fistula is an arteriosclerotic aneurism, infectious aortitis or tuberculosis[20]. The most common cause of secondary aortoenteric fistula is an abdominal vascular graft infected, usually some years after its positioning. Pathophysiology involves a graft and surrounding tissue infection of low aggressiveness, usually caused by S. aureus or E. coli, with causes erosion and communication between the graft and the lumen of the GI tract[21]. Other secondary causes are penetrating ulcers, tumor invasion of the aorta, trauma or radiation. The onset is usually a self-limited premonitory bleeding episode followed, days or weeks later, by a second episode typically massive and life-threatening.

Pancreatic hemosuccus: It is usually caused by the erosion of the splenic artery by a pseudocyst which causes a pseudoaneurysm communicated with the pancreatic duct. Suspicion is arisen by the observation of blood emerging from the ampulla, in a plausible clinical scenario. Angio-CT scan can be diagnostic. Angiography can help to establish a diagnosis, and it can be also therapeutic, but frequently surgery is needed for bleeding control[21].

Oral hypercoagulation therapy has been described as a factor increasing OGIB incidence, worsening prognosis and changing management. In a 2014 study the risk of a severe bleeding episode increased up to 4%-23%, being higher when INR was above 4[22]. Despite this, anticoagulants did not seem to modify the type of lesion that caused the bleeding[23,24].

Risk factors associated with a higher bleeding risk in patients under oral anticoagulants therapy are: (1) Age: In patients older than 70 years annual bleeding risk is 3%; (2) A previous episode of GI bleeding or peptic ulcer increases the risk in up to 2.1% to 6.5%; (3) Comorbidities: Chronic kidney failure, diabetes, cardiac disease, alcohol abuse; and (4) Association with antiplatelet drugs.

Recently, some new anticoagulants have been developed with lower rates of intracranial bleedings[25] but with a likely increase in GI bleeding[26].

For the evaluation of OGIB, particularly mid GI bleeding, angiography, gamma praphy and intraoperative enteroscopy have been classically performed. But the technological improvements with capsule endoscopy, CT-angiography and balloon assisted enteroscopy (BAE) have relegated the classical techniques to a second step and are nowadays used only in selected patients. Moreover, the diagnostic procedure selected in each case depends largely on different factors, as patient’s symptoms, bleeding severity, as well as local expertise and availability, or the need of therapeutic procedures.

Bleeding lesions within reach of upper endoscopy have been indentified in 10%-64% of patients who underwent push enteroscopy and in 24%-25% of patients who underwent BAE because of a suspected OGIB. Nevertheless, few missing lesions are found in lower enteroscopy, with about 7% of findings within the reach of a conventional colonoscope, usually in patients with a previous poor bowel cleansing or with profuse bleeding. In the previously mentioned study, repeated endoscopy (upper or lower) revealed overlooked lesions in 15% of patients[27-32]. However, in another Australian paper, only 4% of 50 patients submitted for enteroscopy had overlooked lesions by upper or lower endoscopy, concluding that repeated endoscopy is not cost-effective[33].

Therefore, despite lesions within the reach of conventional endoscopy might be overlooked, it is not recommended to repeat these procedures in all cases, because this would raise the costs, delaying the definitive diagnosis and overloading endoscopy units. So, it is only recommended to repeat these procedures in selected cases, as in those with previous suboptimal results due to a bad bowel cleansing or with a recurrent GI bleeding with a high suspicion of an upper GI tract origin. If hemobilia or hemosuccus are suspected, upper endoscopy with a duodenoscope is mandatory.

Some authors recommend that, if needed, the second conventional endoscopy should be performed with a push enteroscope, which would allow a deeper exploration in case no other lesions are found in the upper GI tract [34,35].

Neither small bowel series nor enteroclysis have a diagnostic accuracy of more than 5% (22) and 21% respectively[36], with a particular lack of accuracy in flat mucosal lesions, as angiodysplasia, a frequent cause of bleeding cause in the small bowel. The development of capsule endoscopy and enteroscopy has limited its use to a few situations[25,37,38].

The development of other radiologic methods as CT or MRI enteroclysis with new multidetector equipment, offers higher diagnostic capabilities, even for flat vascular lesions[39].

It has been recently added to the diagnostic armamentarium for OGIB, with a reported sensibility and specificity of 79%-90% and 95%-99% respectively[40,41]. It detects bleedings of 0.3-0.5 mL/min with a diagnostic accuracy near 100%, having the advantages of its availability and non-invasiveness. Nevertheless it lacks therapeutic capabilities, requires radiation exposure and need intravenous contrast with a known association with nephropathy and allergic reactions.

For all those reasons, CT angiography should be considered as the first diagnostic procedure in patients with active bleeding and hemodynamic impairment, instead of other procedures with a longer duration as gammagraphy, or more invasive as arteriography, which should be reserved for therapeutic purposes in patients with an active bleeding in CT angiography.

Furthermore, CT angiography has shown its usefulness in patients with an intermittent OGIB and a normal endoscopic study, leading to the detection of unusual cases of OGIB, like stromal tumors up to 1-2 cm. It is also the first option in diverticular disease with an excellent accuracy when studying vascular abnormalities causing GI bleeding, like aortoenteric fistulae.

Gammagraphy consists in the injection of patient’s red cells tagged with Tc99 that survive in the bloodstream up to 24 h, leading to the detection of GI bleedings even of a very low rate (> 0.1 mL/min)[42]. Both properties make the procedure highly sensitive but with poor specificity, finding positive results in around 45% of patients in different published series[43]. The use of colloidal-sulphur Tc99 determines a quicker exploration because there is no need to tag red cells, but it has a lower accuracy because of the quicker dilution of the isotope in the bloodstream.

The main drawback of gammagraphy is its low precision when locating the bleeding source in the bowel, which can be mistaken in up to 25% of patients[44]. For these reasons, as well as for the high rate of false positive and negative results and the lack of therapeutic abilities, this procedure has a very limited role in OGIB, sometimes only as a previous step to angiography[45].

It has diagnostic and therapeutic capabilities. It needs higher bleeding rate than angiography (> 0.5 mL/min), with a better performance in severe cases. However, it allows the diagnosis of non-bleeding lesions as angiodysplasia or tumors and, for this reason, its sensibility shifts between 30% and 47%[38,46], while its specificity is usually near 100%. Nevertheless, angiography is an invasive procedure with associated risks and complications in up to 9.3% of patients[47]. Therefore, it is considered a second line procedure, limited to clinical pictures in which a lesion is likely.

A provocative test, giving to the patient hypo coagulants drugs, fibrinolytic agents or vasodilators, has not shown an improvement on angiography accuracy[48].

As a therapeutic method, it allows the administration of vasoactive agents inside the responsible vessel or to perform an embolization with different substances, leading to bleeding resolution in up to 70%-100% of patients[49,50].

Wireless capsule endoscopy (WCE) has been a great progress in small bowel examination, representing a safe and minimally invasive method for the diagnosis of OGIB.

In a 2010 systematic review, 66% of WCE indications were OGIB, with a diagnostic yield of 60.5%, being angiodysplasia the most frequent finding (50%), followed by ulcers (26.8%) and neoplasms (8.8%)[51]. Different studies have shown that WCE is more useful in overt OGIB than in occult OGIB[51-55]. Other factors related to an increase in WCE yield are[56]: (1) Performance within two weeks after the bleeding episode; (2) Hemoglobin< 10 g/dL; (3) Persistence of GI bleeding for more than 6 mo; and (4) More than one overt bleeding episode.

But WCE has other potential roles, as the detection of overlooked lesions on conventional procedures like upper endoscopy[56] or colonoscopy[57], assessing number, size and location of lesions for a better planning of the therapeutic procedure. Indeed, in a 2008 study[58] from our group, 30 patients with angiodysplasia found on CE were followed for one year, observing that patients with bigger angiodysplasia (> 1 cm) have a higher clinical impact (lower hemoglobin rates, higher transfusion requirements) and therefore higher needs of therapeutic interventions after WCE (75% vs 18.2%), which lead to lower rates of rebleeding. In conclusion, this paper found that angiodysplasia size (> 1 cm) and number (> 10) is related with a higher mortality (20% vs 4% and 25% vs 0% respectively).

When compared with push enteroscopy or small bowel series, WCE has proved to be superior in OGIB: In a metaanalysis published by Triester in 2005, diagnostic yield of WCE was 63% compared to 28% and 6% of push enteroscopy and small bowel series respectively. Another meta-analysis of the same year showed similar results[59-61].

Regarding other procedures, CE has shown a higher yield than angiography or CT-angiography but very similar to BAE, with the differences of its invasiveness and its ability to explore the whole small bowel in a single procedure[62-64].

This higher yield has shown to have a direct impact on management of two thirds patients with OGIB[65,66], as well as a high negative predictive value, with a rebleeding rate after a normal CE in the following 19 mo of 5.6%[67].

Therefore, CE is a first line procedure for OGIB management, although it is far from the ideal. Important disadvantages, like biopsy sampling, lack of therapeutic abilities, lack of a remote motion control, battery limitations etc. imply the need of other methods to manage those patients[68,69].

Anyway, significant research is being conducted in this field, with devices that will likely allow biopsy sampling, therapeutic interventions, real time motion control from outside the patient by means of magnetic fields control or articulated arms (Spider Pill), improvements in batteries durability etc. Some of those advances have already been incorporated, as bleeding lesions detection improvements by pattern differences in color wavelength (FICE-CE, Given Imagin)[70].

Enteroscopy allows the endoscopic observation of the small bowel beyond the angle of Treitz by means of an enteroscope.

Push enteroscopy: Until recently, push enteroscopy (PE) has been the standard of care in patients with OGIB, after a normal upper endoscopy and colonoscopy. It consists in the passage of an enteroscope by mouth, which makes possible the exploration of a variable length of the small bowel, ranging from 30-160 cm beyond the angle of Treitz[71]. PE permits only a partial vision of the small bowel, but its main indication is still OGIB, with a global diagnostic yield of 12%-80% and better results in overt OGIB.

In conclusion, PE has the advantage of its therapeutic capabilities but also the important drawbacks of a partial exploration of the GI tract and its invasiveness. Thus, it should be carefully used for previously identified lesions which are likely within the reach of this enteroscope[25,71-75].

Double balloon enteroscopy: Double balloon enteroscopy (DBE) has been a great improvement in small bowel exploration, because it provides a complete examination of the bowel lumen, as well as biopsy sampling and therapeutic abilities[76].

First described in 2001, it was widely available in 2004, consisting in an enteroscope with a balloon attached to its tip, as well as another balloon over an overtube. The alternative inflation and progression with the overtube and the balloon-enteroscope system provides a deeper progression through the small bowel, with a significantly increased mean bowel length explored as compared to PE[77,78].

The combination of lower and upper DBE grants a visualization of the whole length of the small bowel, which is not always needed[79].

Diagnostic yield of DBE in OGIB ranges between 47%-80%[5], similar to that of WCE[58]. Its yield is increased when the procedure is performed within one month after the bleeding event.

Keeping in sight the similar diagnostic yield of WCE and DBE, they are actually considered complementary procedures[80], being WCE the first tool to be used, because of its lower cost, less invasiveness and higher availability. Information from WCE examination is helpful to decide between an upper or lower enteroscopy. In case we don’t have a previous WCE, or if an upper and lower enteroscopy is needed, it is usually recommended to begin the endoscopic examination with the upper enteroscopy, because it is technically easier and has an increased likelihood of finding the causative lesion[81,82].

The main drawback of DBE is that a complete small bowel examination is not feasible in up to 29%[5], it needs sedation (usually under general anesthesia), its availability is limited to referral centers, and it has a prolonged examination time and other difficulties usually found in the lower approach due to poor bowel preparation, abdominal adhesions etc.

Nevertheless, DBE is a safe procedure, with less than 1% complications, being the most usual perforation (0.4%), pancreatitis (0.3%), and ileus[83,84]. Complications are not related to age, but with therapeutic maneuvers or anatomical abnormalities of the bowel (i.e., previous surgeries, abdominal radiotherapy or intestinal lymphoma treated with chemotherapy)[6].

Other enteroscopies: Other enteroscopes used with overtube and balloons are: (1) Single balloon enteroscopy (Olympus Inc.): Exploration times and depth of insertion in small bowel enteroscopy are similar to these of DBE. In a 2010 paper[85] 100 patients were studied (50 patients with DBE and 50 with SBE) achieving DBE a higher number of complete enteroscopies when compared with SBE (66% vs 22%) and a higher number of findings. However, in this study, a system different from the original SBE (Olympus®) was used (Fujifilm®), having a different flexibility and balloon pressure. Later, Takano et al[86] had to stop prematurely a study comparing DBE with SBE, because of the differences in complete enteroscopies between both systems (57.1% vs 0%), finding no differences with regards to findings or complications[86]. Finally, in 2011 and 2012 two studies with 130 and 107 patients respectively[87,88] showed no differences between both systems regarding depth of insertion, complete bowel examination, complications and findings; (2) Spiral enteroscopy (Endo-Ease Discovery SB, Spirus Medical Inc.): The device includes an overtube with a helical portion which grasps the bowel folds, reaching as far as 200 cm beyond the angle of Treitz; and (3) Shapelock (USGI Medical Inc.): It consists in an overtube with multiple titanium rings, joined by four titanium wires and covered by a detachable sheath. When tension is applied on the wires, the overtube is fixed, allowing the passage of the enteroscope. Today, it has more applicability in patients with altered anatomy due to previous surgeries, in incomplete colonoscopy and in NOTES[89-92].

Intraoperative enteroscopy: It has been considered the gold standard for small bowel examination for long time[4], and although balloon assisted enteroscopy (BAE) is preferred because it is less invasive and have similar results in the diagnosis and management of small bowel disorders, the IE is an important reserve tool. It consists in the insertion of the endoscope through an enterotomy, exploring the mucosa while the surgeon facilitates the advance of the endoscope and observes the serosal surface. Palpation and transilumination play an important role in this procedure, which allows the whole bowel examination in more than 90% of patients.

Intraoperative enteroscopy (IE) has a diagnostic yield of 50%-100%[4,93], with therapeutic possibilities, but it is invasive. 12%-33%[77,78] of complications and 8%[94-96] of mortality limit its use to cases in which the other diagnostic methods are contraindicated or impossible, and always in patients with clinically significant OGIB[93-98].

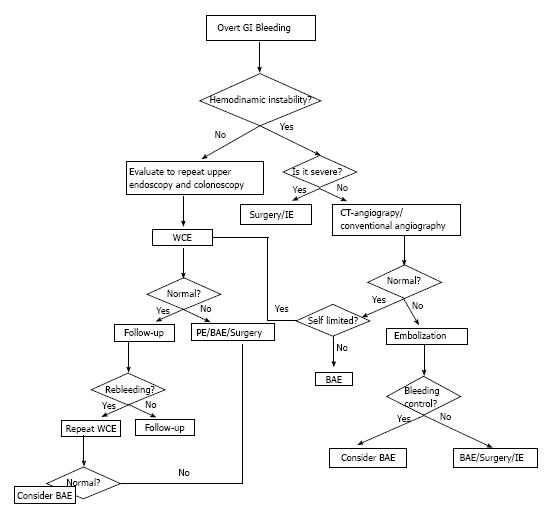

In a patient with OGIB, after conventional upper endoscopy and colonoscopy, we should consider to repeat colonoscopy when a poor bowel cleansing is reported, or when we suspect an incomplete colonic evaluation. Upper endoscopy should be repeated if a strong suspicion of an upper GI tract bleeding lesion is still a concern despite a previous normal upper endoscopy.

Once a bleeding cause within reach to conventional endoscopy has been ruled out, depending on patient’s situation, an evaluation of the small bowel by WCE and BAE (balloon assisted enteroscopy, DBE or SBE) should be the next step, beginning with the less invasive one, which is WCE[5,67,75,99].

After normal WCE, if the bleeding stops spontaneously, a conservative attitude is recommended, with a clinical follow-up of the patient. If there is a strong suspicion of small bowel disease, even with a previous normal WCE, BAE should be performed[100].

Nevertheless, some authors think that if pretest likelihood of a correct diagnosis and treatment with BAE is higher than 25%-30%, we should proceed directly with BAE, because it is the most cost-effective option[101,102]. Moreover, in centers with a high number of patients and experienced endoscopists, DBE can be considered as a first step procedure in some clinical settings[102].

After rebleeding, repeated WCE finds lesions in up to 20%-35% of patients. Those lesions can be found and treated afterwards with BAE, which can also detect up to 30% of lesions previously overlooked by WCE[103-105].

If a patient presents hemodynamic instability and an active bleeding, angiography and IE should be the first diagnostic procedures. CT angiography is increasingly being used in this setting, because it offers an accurate diagnosis in many patients, it is less invasive, widely available and quick. Anatomical location of the lesion is usually accurate with few complications. After detecting a lesion by CT-angiography, conventional angiography or surgery can be used to apply the specific therapy[106] (Figure 1).

Therapy is directed by the type of lesion and its location. There are three major types of available therapies.

Hormonal therapy (estrogens and progesterone) was initially explored by Koch et al in 1952 after observing that a patients with hereditary hemorrhagic theleangiectasia (HHT) whose bleeding varied depending on her menstrual cycle. The mechanism of action is not well understood, but there are several theories: (1) Estrogen and progesterone receptors have been detected in nasal and epidermal telangiectatic lesions in patients with HHT, and the hormone-receptor binding improved endothelial integrity in patients with HHT; (2) In animals this treatment improved vascular stasis within the mesenteric microcirculation and decreased the mucosal blood flow; (3) In patients on dialysis, estrogens shorten bleeding time by the reduction of endothelial prostacyclin production; and (4) Finally hormones may also decrease vascular endothelial growth factor.

Estrogens and progesterone therapy has been widely used in OGIB, with contradictory results, although some reports have observed a significant reduction in transfusion requirements, and even a complete resolution of bleeding.

A study of 43 patients, 38 of which were treated with hormonal therapy and followed for a mean time of 535 d (range 25-1551 d), reported benefits in patients with bleeding from sporadic angiodysplasia[108]. However, this has not been confirmed in other studies. The best data come from a multicenter, placebo-controlled trial involving 72 noncirrhotic patients which had bleedings from documented angiodysplasia; there was no benefit from hormonal therapy[109]. Based on these findings, hormonal therapy seems to have poor therapeutic advantages in patients with sporadic angiodysplasia.

Some other papers do not recommend their use because of their lack of beneficial effects on OGIB and their adverse events (thrombosis, gynecomastia, loss of libido in males, metrorragia…). In general, their efficacy has not been proved, except for the treatment of hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia, von Willebrand disease, chronic kidney failure and gastric antral vascular ectasia (GAVE), in which hormonal therapy reduces transfusion requirements but not the size or number of lesions[98-100].

Somatostatin analogs: Octeotride reduces splacnic arterial flow by inhibiting angiogenesis and endothelial related growth factors[101-103]. Also, octeotride can inhibit angiogenesis by inhibiting endothelial cell proliferation. It has shown efficacy in acute and chronic GI bleeding, and can be used in patients with contraindications or a poor response to hormonal therapy. In Rossini et al study[110], treatment with octreotide in 3 patients decreased the need for blood transfusions during the follow-up period (8 to 17 mo). Other authors have published similar results[111], and have observed comparable side effects including diarrhea, steatorrhea, or changes in glucose metabolism.

A 2010 meta-analysis[112] analyzed 3 studies with a total of 62 patients, observing that 76% of patients responded to this therapy, achieving a significant reduction in transfusion requirements.

Depot formulations like LAR-Octeotride, which allow intramuscular administration once a month, have gained acceptance in selected cases[113,114]. In a study with 15 patients[115] treated with LAR-Octeotride for a recurrent bleeding from gastrointestinal angiodysplasia, the proportion of patients who experienced a bleeding event was lower during treatment than prior to treatment (20 vs 73), median transfusion requirements were reduced (2 vs 10 units), and median hemoglobin levels were higher during therapy (10 vs 7 g/dL).

Non-selective beta-blockers: They reduce splacnic flow, pulse and cardiac output. They are usually used in portal hypertension related OGIB and monotherapy or in association with LAR-Octeotride.

Thalidomide: It was retired in the 60s because of its teratogenic effect. However, thalidomide has recently shown to be an effective anti-inflammatory treatment in Crohn’s disease. In addition to its anti-inflammatory effects, it also displays antiangiogenic activity, which may be useful for the treatment of GI bleeding. It can be taken orally and it could be used in patients with contraindications to other therapies. Obviously it is forbidden in childbearing aged women and in patients with peripheral neuropathy. It must be used cautiously in patients with cardiovascular or neurologic diseases, chronic kidney or liver failure and in immunosuppressed patients.

Some reports show promising outcomes in bleeding control[112]. In a randomized trial in 2011[116] patients treated with thalidomide were more likely than those treated with iron supplements to experience a positive clinical outcome (71% vs 4%).

Other drugs: (1) Antifibrinolitics: Tranexamic acid is an antifibrinolytic agent whose haemostatic effect is due to the inhibition of plasminogen activation in body fluids and tissues. Epsilon-aminocaproic acid has controlled chronic bleeding in patients suffering from HHT. These drugs have a prothrombotic activity and, for this reason, coagulation abnormalities or thrombophilia have to be ruled out before initiating the therapy; (2) Danazol: There are two single reports with positive results after hormonal therapy failure in patients with hereditary hemorrhagic teleangiectasia; (3) Desmopresin; and (4) Recombinant factor VII: Reserved to cases of massive overt OGIB.

There are different methods, injection therapies, thermal methods or mechanical devices which can be used with different endoscopes, depending on the location of the bleeding cause.

Argon plasma coagulation: It is safe and the most common and successful method used to treat angiodysplasia because of its easy application (especially for large superficial lesions), low cost, and reported limited depth of coagulation. Argon plasma coagulation (APC) has been used for a variety of bleeding lesions, including angiodysplasia, in these lesions submucosal saline injection prior to treatment with APC may protect against deep wall injury.

In a study of 50 patients with small bowel lesions, 44 patients were treated with APC for angiodysplasia[117]. After a mean follow-up of 55 mo, hemoglobin levels increased from a mean of 7.6 g/dL prior to treatment to 11.0 g/dL following it, and there was a significant decrease in the number of patients requiring blood transfusions. However, small bowel bleeding recurred in 21 of the patients treated with APC. A later study with 98 patients[118] reported similar results. The risk factors associated with rebleeding were the number of lesions and the presence of valvular and or arrhythmic cardiac disease.

Electrocoagulation: Bipolar or heater probe coagulation is effective for treatment of angiodysplasia in the colon or upper gastrointestinal tract. The risk of perforation with heater probe coagulation may be increased in the colon and small bowel, beyond the duodenum. Monopolar coagulation may be less effective and is associated with an increased rate of complications.

Mechanical hemostasis: Mechanical hemostatic methods such as endoscopic clips have the advantage of avoiding tissue injury, which may be particularly desirable in patients taking anticoagulants and/or antiplatelet agents, or in patients with coagulation defects.

Another mechanical method that has been described in some case reports is band ligation[119], that is safe and effective for the treatment of acutely bleeding small bowel vascular lesions with similar results to APC (recurrent bleeding in 43%) and which can be a definitive treatment for Dieulafoy’s lesion.

Angiography is indicated in patients with GI bleeding who fail to respond to medical and/or endoscopic therapy, as an alternative to surgery in hemodynamically unstable patients with severe bleeding or for patients with ongoing or recurrent bleeding following attempts to control the bleeding endoscopically. Angiographic therapies include the infusion of vasoactive drugs (vasopressin) or the delivery of agents to mechanically occlude the vascular supply of the bleeding lesion (embolization).

Vasopressin causes generalized vasoconstriction via a direct action upon vessel walls, especially the arterioles, capillaries, and venules. It should be used with caution in patients with coronary artery disease, congestive cardiomyopathy, severe hypertension, or severe peripheral vascular disease. Other side effects are arrhythmias and water retention leading to hyponatremia.

Agents used for embolization include biodegradable gelatin sponge, polyvinyl alcohol particles, liquid agents, and metallic coils. Microcoils have become the preferred agent for embolizing bleeding vessels and can be deployed by means of a microcatheter to the site of bleeding. The complications of embolization include those associated with arteriography itself (e.g., hematomas, arterial thrombosis, dissection, embolism, and pseudoaneurysm formation), and bowel infarction.

The choice between vasopressin and embolization should be individualized for each patient, taking into account angiography experience. Embolization with microcoils may be more successful than vasopressin infusion (95% vs 80%-90%)[120,121]) but it is associated with a higher rate of complications.

Initial hemostasis may be achieved in up to 80%-95% of patients in whom angiographic therapy is technically feasible, but rebleeding is a common problem (9%-56% in embolization and 5%-50% in intra-arterial vasopressin infusion).

Surgical therapy is reserved for patients with a known bleeding cause, found with other methods, patients with increasing transfusion requirements or life-threatening bleedings from clearly identified origins, or for cases in which haemodinamic instability does not allow the clinicians to complete the diagnostic algorithm and an IE is mandatory. In this last situation, rebleeding is usual[86,87].

Despite technological advances, OGIB is still a diagnostic challenge for gastroenterologists, with important hospital resources consumption and delayed diagnoses. WCE is the most cost-effective diagnostic procedure to identify the bleeding source and its location. In selected cases, with an outstanding severity, CT-angiography is an alternative.

Although therapy depends on the bleeding cause, BAE plays an important role in the management of lesions found in WCE. It is less aggressive than intraoperative enteroscopy and has a high index of success. A pharmacological alternative to surgery or endoscopy are depot formulations of somatostatin analogs.

P- Reviewer: Calabrese C, Moeschler O, Misra SP, Sung J, Yang MH S- Editor: Ji FF L- Editor: A E- Editor: Lu YJ

| 1. | Ell C, May A. Mid-gastrointestinal bleeding: capsule endoscopy and push-and-pull enteroscopy give rise to a new medical term. Endoscopy. 2006;38:73-75. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 78] [Cited by in RCA: 70] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Prakash C, Zuckerman GR. Acute small bowel bleeding: a distinct entity with significantly different economic implications compared with GI bleeding from other locations. Gastrointest Endosc. 2003;58:330-335. [PubMed] |

| 3. | Moawad FJ, Veerappan GR, Wong RK. Small bowel is the primary source of obscure gastrointestinal bleeding. Gastroenterology. 2008;135:1016. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Gralnek IM. Obscure-overt gastrointestinal bleeding. Gastroenterology. 2005;128:1424-1430. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 42] [Cited by in RCA: 44] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Raju GS, Gerson L, Das A, Lewis B. American Gastroenterological Association (AGA) Institute technical review on obscure gastrointestinal bleeding. Gastroenterology. 2007;133:1697-1717. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 379] [Cited by in RCA: 338] [Article Influence: 18.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Mujica VR, Barkin JS. Occult gastrointestinal bleeding. General overview and approach. Gastrointest Endosc Clin N Am. 1996;6:833-845. [PubMed] |

| 7. | Meyer CT, Troncale FJ, Galloway S, Sheahan DG. Arteriovenous malformations of the bowel: an analysis of 22 cases and a review of the literature. Medicine (Baltimore). 1981;60:36-48. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 143] [Cited by in RCA: 126] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Sami SS, Al-Araji SA, Ragunath K. Review article: gastrointestinal angiodysplasia - pathogenesis, diagnosis and management. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2014;39:15-34. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 191] [Cited by in RCA: 150] [Article Influence: 13.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Foutch PG. Angiodysplasia of the gastrointestinal tract. Am J Gastroenterol. 1993;88:807-818. [PubMed] |

| 10. | Scheffer SM, Leatherman LL. Resolution of Heyde’s syndrome of aortic stenosis and gastrointestinal bleeding after aortic valve replacement. Ann Thorac Surg. 1986;42:477-480. [PubMed] |

| 11. | Islam S, Cevik C, Madonna R, Frandah W, Islam E, Islam S, Nugent K. Left ventricular assist devices and gastrointestinal bleeding: a narrative review of case reports and case series. Clin Cardiol. 2013;36:190-200. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 73] [Cited by in RCA: 78] [Article Influence: 6.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Soulellis CA, Carpentier S, Chen YI, Fallone CA, Barkun AN. Lower GI hemorrhage controlled with endoscopically applied TC-325 (with videos). Gastrointest Endosc. 2013;77:504-507. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Sagar J, Kumar V, Shah DK. Meckel’s diverticulum: a systematic review. J R Soc Med. 2006;99:501-505. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 374] [Cited by in RCA: 196] [Article Influence: 10.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Yahchouchy EK, Marano AF, Etienne JC, Fingerhut AL. Meckel’s diverticulum. J Am Coll Surg. 2001;192:658-662. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 174] [Cited by in RCA: 169] [Article Influence: 7.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Lee YT, Walmsley RS, Leong RW, Sung JJ. Dieulafoy’s lesion. Gastrointest Endosc. 2003;58:236-243. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Lara LF, Sreenarasimhaiah J, Tang SJ, Afonso BB, Rockey DC. Dieulafoy lesions of the GI tract: localization and therapeutic outcomes. Dig Dis Sci. 2010;55:3436-3441. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 37] [Cited by in RCA: 51] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Ferguson A, Arranz E, O’Mahony S. Clinical and pathological spectrum of coeliac disease--active, silent, latent, potential. Gut. 1993;34:150-151. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 259] [Cited by in RCA: 264] [Article Influence: 8.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Moreno RD, Harris M, Bryk HB, Pachter HL, Miglietta MA. Late presentation of a hepatic pseudoaneurysm with hemobilia after angioembolization for blunt hepatic trauma. J Trauma. 2007;62:1048-1050. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Bloechle C, Izbicki JR, Rashed MY, el-Sefi T, Hosch SB, Knoefel WT, Rogiers X, Broelsch CE. Hemobilia: presentation, diagnosis, and management. Am J Gastroenterol. 1994;89:1537-1540. [PubMed] |

| 20. | Saers SJ, Scheltinga MR. Primary aortoenteric fistula. Br J Surg. 2005;92:143-152. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 166] [Cited by in RCA: 187] [Article Influence: 9.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Suter M, Doenz F, Chapuis G, Gillet M, Sandblom P. Haemorrhage into the pancreatic duct (Hemosuccus pancreaticus): recognition and management. Eur J Surg. 1995;161:887-892. [PubMed] |

| 22. | Nantes O, Zozaya JM, Montes R, Hermida J. Gastrointestinal lesions and characteristics of acute gastrointestinal bleeding in acenocoumarol-treated patients. Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2014;S0210-5705(14)00024-7. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Barada K, Abdul-Baki H, El Hajj II, Hashash JG, Green PH. Gastrointestinal bleeding in the setting of anticoagulation and antiplatelet therapy. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2009;43:5-12. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 38] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Thomopoulos KC, Mimidis KP, Theocharis GJ, Gatopoulou AG, Kartalis GN, Nikolopoulou VN. Acute upper gastrointestinal bleeding in patients on long-term oral anticoagulation therapy: endoscopic findings, clinical management and outcome. World J Gastroenterol. 2005;11:1365-1368. [PubMed] |

| 25. | Rasmussen LH, Larsen TB, Graungaard T, Skjøth F, Lip GY. Primary and secondary prevention with new oral anticoagulant drugs for stroke prevention in atrial fibrillation: indirect comparison analysis. BMJ. 2012;345:e7097. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 95] [Cited by in RCA: 99] [Article Influence: 7.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Holster IL, Valkhoff VE, Kuipers EJ, Tjwa ET. New oral anticoagulants increase risk for gastrointestinal bleeding: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Gastroenterology. 2013;145:105-112.e15. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 263] [Cited by in RCA: 281] [Article Influence: 23.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 27. | Zaman A, Katon RM. Push enteroscopy for obscure gastrointestinal bleeding yields a high incidence of proximal lesions within reach of a standard endoscope. Gastrointest Endosc. 1998;47:372-376. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 132] [Cited by in RCA: 108] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Descamps C, Schmit A, Van Gossum A. “Missed” upper gastrointestinal tract lesions may explain “occult” bleeding. Endoscopy. 1999;31:452-455. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 83] [Cited by in RCA: 73] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Chak A, Cooper GS, Canto MI, Pollack BJ, Sivak MV. Enteroscopy for the initial evaluation of iron deficiency. Gastrointest Endosc. 1998;47:144-148. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 43] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Fry LC, Bellutti M, Neumann H, Malfertheiner P, Mönkemüller K. Incidence of bleeding lesions within reach of conventional upper and lower endoscopes in patients undergoing double-balloon enteroscopy for obscure gastrointestinal bleeding. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2009;29:342-349. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 80] [Cited by in RCA: 71] [Article Influence: 4.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Tee HP, Kaffes AJ. Non-small-bowel lesions encountered during double-balloon enteroscopy performed for obscure gastrointestinal bleeding. World J Gastroenterol. 2010;16:1885-1889. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Leaper M, Johnston MJ, Barclay M, Dobbs BR, Frizelle FA. Reasons for failure to diagnose colorectal carcinoma at colonoscopy. Endoscopy. 2004;36:499-503. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 89] [Cited by in RCA: 88] [Article Influence: 4.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Gilbert D, O’Malley S, Selby W. Are repeat upper gastrointestinal endoscopy and colonoscopy necessary within six months of capsule endoscopy in patients with obscure gastrointestinal bleeding? J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;23:1806-1809. [PubMed] |

| 34. | Lin S, Branch MS, Shetzline M. The importance of indication in the diagnostic value of push enteroscopy. Endoscopy. 2003;35:315-321. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Rabe FE, Becker GJ, Besozzi MJ, Miller RE. Efficacy study of the small-bowel examination. Radiology. 1981;140:47-50. [PubMed] |

| 36. | Moch A, Herlinger H, Kochman ML, Levine MS, Rubesin SE, Laufer I. Enteroclysis in the evaluation of obscure gastrointestinal bleeding. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1994;163:1381-1384. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 79] [Cited by in RCA: 79] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Jonnalagadda S, Prakash C. Intestinal strictures can impede wireless capsule enteroscopy. Gastrointest Endosc. 2003;57:418-420. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | Graça BM, Freire PA, Brito JB, Ilharco JM, Carvalheiro VM, Caseiro-Alves F. Gastroenterologic and radiologic approach to obscure gastrointestinal bleeding: how, why, and when? Radiographics. 2010;30:235-252. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 51] [Cited by in RCA: 58] [Article Influence: 3.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | Huprich JE, Fletcher JG, Alexander JA, Fidler JL, Burton SS, McCullough CH. Obscure gastrointestinal bleeding: evaluation with 64-section multiphase CT enterography--initial experience. Radiology. 2008;246:562-571. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 124] [Cited by in RCA: 110] [Article Influence: 6.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 40. | Kennedy DW, Laing CJ, Tseng LH, Rosenblum DI, Tamarkin SW. Detection of active gastrointestinal hemorrhage with CT angiography: a 4(1/2)-year retrospective review. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2010;21:848-855. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 54] [Cited by in RCA: 56] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 41. | Yoon W, Jeong YY, Shin SS, Lim HS, Song SG, Jang NG, Kim JK, Kang HK. Acute massive gastrointestinal bleeding: detection and localization with arterial phase multi-detector row helical CT. Radiology. 2006;239:160-167. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 224] [Cited by in RCA: 188] [Article Influence: 9.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 42. | Som P, Oster ZH, Atkins HL, Goldman AG, Sacker DF, Harold WH, Fairchild RG, Richards P, Brill AB. Detection of gastrointestinal blood loss with 99mTc-labeled, heat-treated red blood cells. Radiology. 1981;138:207-209. [PubMed] |

| 43. | Zuckerman GR, Prakash C, Askin MP, Lewis BS. AGA technical review on the evaluation and management of occult and obscure gastrointestinal bleeding. Gastroenterology. 2000;118:201-221. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 339] [Cited by in RCA: 321] [Article Influence: 12.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 44. | Hunter JM, Pezim ME. Limited value of technetium 99m-labeled red cell scintigraphy in localization of lower gastrointestinal bleeding. Am J Surg. 1990;159:504-506. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 114] [Cited by in RCA: 91] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 45. | Ng DA, Opelka FG, Beck DE, Milburn JM, Witherspoon LR, Hicks TC, Timmcke AE, Gathright JB. Predictive value of technetium Tc 99m-labeled red blood cell scintigraphy for positive angiogram in massive lower gastrointestinal hemorrhage. Dis Colon Rectum. 1997;40:471-477. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 78] [Cited by in RCA: 58] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 46. | Fiorito JJ, Brandt LJ, Kozicky O, Grosman IM, Sprayragen S. The diagnostic yield of superior mesenteric angiography: correlation with the pattern of gastrointestinal bleeding. Am J Gastroenterol. 1989;84:878-881. [PubMed] |

| 47. | Egglin TK, O‘Moore PV, Feinstein AR, Waltman AC. Complications of peripheral arteriography: a new system to identify patients at increased risk. J Vasc Surg. 1995;22:787-794. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 93] [Cited by in RCA: 78] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 48. | Bloomfeld RS, Smith TP, Schneider AM, Rockey DC. Provocative angiography in patients with gastrointestinal hemorrhage of obscure origin. Am J Gastroenterol. 2000;95:2807-2812. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 91] [Cited by in RCA: 83] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 49. | Miller M, Smith TP. Angiographic diagnosis and endovascular management of nonvariceal gastrointestinal hemorrhage. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 2005;34:735-752. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 45] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 50. | Busch OR, van Delden OM, Gouma DJ. Therapeutic options for endoscopic haemostatic failures: the place of the surgeon and radiologist in gastrointestinal tract bleeding. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. 2008;22:341-354. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 51. | Liao Z, Gao R, Xu C, Li ZS. Indications and detection, completion, and retention rates of small-bowel capsule endoscopy: a systematic review. Gastrointest Endosc. 2010;71:280-286. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 561] [Cited by in RCA: 476] [Article Influence: 31.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 52. | Fireman Z, Kopelman Y. The role of video capsule endoscopy in the evaluation of iron deficiency anaemia. Dig Liver Dis. 2004;36:97-102. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 53. | Rastogi A, Schoen RE, Slivka A. Diagnostic yield and clinical outcomes of capsule endoscopy. Gastrointest Endosc. 2004;60:959-964. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 84] [Cited by in RCA: 91] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 54. | May A, Wardak A, Nachbar L, Remke S, Ell C. Influence of patient selection on the outcome of capsule endoscopy in patients with chronic gastrointestinal bleeding. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2005;39:684-688. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 55. | Bresci G, Parisi G, Bertoni M, Tumino E, Capria A. The role of video capsule endoscopy for evaluating obscure gastrointestinal bleeding: usefulness of early use. J Gastroenterol. 2005;40:256-259. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 105] [Cited by in RCA: 104] [Article Influence: 5.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 56. | Sidhu R, Sanders DS, McAlindon ME. Does capsule endoscopy recognise gastric antral vascular ectasia more frequently than conventional endoscopy? J Gastrointestin Liver Dis. 2006;15:375-377. [PubMed] |

| 57. | Estévez E, González-Conde B, Vázquez-Iglesias JL, Alonso PA, Vázquez-Millán Mde L, Pardeiro R. Incidence of tumoral pathology according to study using capsule endoscopy for patients with obscure gastrointestinal bleeding. Surg Endosc. 2007;21:1776-1780. [PubMed] |

| 58. | Redondo-Cerezo E, Gómez-Ruiz CJ, Sánchez-Manjavacas N, Viñuelas M, Jimeno C, Pérez-Vigara G, Morillas J, Pérez-García JI, García-Cano J, Pérez-Sola A. Long-term follow-up of patients with small-bowel angiodysplasia on capsule endoscopy. Determinants of a higher clinical impact and rebleeding rate. Rev Esp Enferm Dig. 2008;100:202-207. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 59. | Marmo R, Rotondano G, Piscopo R, Bianco MA, Cipolletta L. Meta-analysis: capsule enteroscopy vs. conventional modalities in diagnosis of small bowel diseases. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2005;22:595-604. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 153] [Cited by in RCA: 142] [Article Influence: 7.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 60. | Lewis BS, Eisen GM, Friedman S. A pooled analysis to evaluate results of capsule endoscopy trials. Endoscopy. 2005;37:960-965. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 202] [Cited by in RCA: 187] [Article Influence: 9.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 61. | Triester SL, Leighton JA, Leontiadis GI, Fleischer DE, Hara AK, Heigh RI, Shiff AD, Sharma VK. A meta-analysis of the yield of capsule endoscopy compared to other diagnostic modalities in patients with obscure gastrointestinal bleeding. Am J Gastroenterol. 2005;100:2407-2418. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 433] [Cited by in RCA: 419] [Article Influence: 21.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 62. | Saperas E, Dot J, Videla S, Alvarez-Castells A, Perez-Lafuente M, Armengol JR, Malagelada JR. Capsule endoscopy versus computed tomographic or standard angiography for the diagnosis of obscure gastrointestinal bleeding. Am J Gastroenterol. 2007;102:731-737. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 133] [Cited by in RCA: 125] [Article Influence: 6.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 63. | Pasha SF, Leighton JA, Das A, Harrison ME, Decker GA, Fleischer DE, Sharma VK. Double-balloon enteroscopy and capsule endoscopy have comparable diagnostic yield in small-bowel disease: a meta-analysis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;6:671-676. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 270] [Cited by in RCA: 273] [Article Influence: 16.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 64. | Hartmann D, Schmidt H, Bolz G, Schilling D, Kinzel F, Eickhoff , Huschner W, Möller K, Jakobs R, Reitzig P. A prospective two-center study comparing wireless capsule endoscopy with intraoperative enteroscopy in patients with obscure GI bleeding. Gastrointest Endosc. 2005;61:826-832. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 230] [Cited by in RCA: 201] [Article Influence: 10.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 65. | Redondo-Cerezo E, Pérez-Vigara G, Pérez-Sola A, Gómez-Ruiz CJ, Chicano MV, Sánchez-Manjavacas N, Morillas J, Pérez-García JI, García-Cano J. Diagnostic yield and impact of capsule endoscopy on management of patients with gastrointestinal bleeding of obscure origin. Dig Dis Sci. 2007;52:1376-1381. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 42] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 66. | Mylonaki M, Fritscher-Ravens A, Swain P. Wireless capsule endoscopy: a comparison with push enteroscopy in patients with gastroscopy and colonoscopy negative gastrointestinal bleeding. Gut. 2003;52:1122-1126. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 342] [Cited by in RCA: 316] [Article Influence: 14.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 67. | Lai LH, Wong GL, Chow DK, Lau JY, Sung JJ, Leung WK. Long-term follow-up of patients with obscure gastrointestinal bleeding after negative capsule endoscopy. Am J Gastroenterol. 2006;101:1224-1228. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 118] [Cited by in RCA: 112] [Article Influence: 5.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 68. | Swain P, Fritscher-Ravens A. Role of video endoscopy in managing small bowel disease. Gut. 2004;53:1866-1875. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 54] [Cited by in RCA: 46] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 69. | Ben-Soussan E, Savoye G, Antonietti M, Ramirez S, Lerebours E, Ducrotté P. Factors that affect gastric passage of video capsule. Gastrointest Endosc. 2005;62:785-790. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 51] [Cited by in RCA: 58] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 70. | Nogales Rincón O, Merino Rodríguez B, González Asanza C, Fernández-Pacheco PM. [Utility of capsule endoscopy with flexible spectral imaging color enhancement in the diagnosis of small bowel lesions]. Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013;36:63-68. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 71. | Sidhu R, Sanders DS, Morris AJ, McAlindon ME. Guidelines on small bowel enteroscopy and capsule endoscopy in adults. Gut. 2008;57:125-136. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 155] [Cited by in RCA: 141] [Article Influence: 8.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 72. | Benz C, Jakobs R, Riemann JF. Do we need the overtube for push-enteroscopy? Endoscopy. 2001;33:658-661. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 49] [Cited by in RCA: 50] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 73. | Taylor AC, Chen RY, Desmond PV. Use of an overtube for enteroscopy--does it increase depth of insertion? A prospective study of enteroscopy with and without an overtube. Endoscopy. 2001;33:227-230. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 57] [Cited by in RCA: 43] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 74. | Carey EJ, Fleischer DE. Investigation of the small bowel in gastrointestinal bleeding--enteroscopy and capsule endoscopy. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 2005;34:719-734. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 75. | Mergener K, Ponchon T, Gralnek I, Pennazio M, Gay G, Selby W, Seidman EG, Cellier C, Murray J, de Franchis R. Literature review and recommendations for clinical application of small-bowel capsule endoscopy, based on a panel discussion by international experts. Consensus statements for small-bowel capsule endoscopy, 2006/2007. Endoscopy. 2007;39:895-909. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 133] [Cited by in RCA: 118] [Article Influence: 6.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 76. | May A, Nachbar L, Pohl J, Ell C. Endoscopic interventions in the small bowel using double balloon enteroscopy: feasibility and limitations. Am J Gastroenterol. 2007;102:527-535. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 168] [Cited by in RCA: 161] [Article Influence: 8.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 77. | May A, Nachbar L, Schneider M, Ell C. Prospective comparison of push enteroscopy and push-and-pull enteroscopy in patients with suspected small-bowel bleeding. Am J Gastroenterol. 2006;101:2016-2024. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 99] [Cited by in RCA: 95] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 78. | Matsumoto T, Moriyama T, Esaki M, Nakamura S, Iida M. Performance of antegrade double-balloon enteroscopy: comparison with push enteroscopy. Gastrointest Endosc. 2005;62:392-398. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 59] [Cited by in RCA: 55] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 79. | Yamamoto H, Sekine Y, Sato Y, Higashizawa T, Miyata T, Iino S, Ido K, Sugano K. Total enteroscopy with a nonsurgical steerable double-balloon method. Gastrointest Endosc. 2001;53:216-220. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 896] [Cited by in RCA: 861] [Article Influence: 35.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 80. | Alexander JA, Leighton JA. Capsule endoscopy and balloon-assisted endoscopy: competing or complementary technologies in the evaluation of small bowel disease? Curr Opin Gastroenterol. 2009;25:433-437. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 81. | Gay G, Delvaux M, Fassler I. Outcome of capsule endoscopy in determining indication and route for push-and-pull enteroscopy. Endoscopy. 2006;38:49-58. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 168] [Cited by in RCA: 150] [Article Influence: 7.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 82. | Gerson LB. Double-balloon enteroscopy: the new gold standard for small-bowel imaging? Gastrointest Endosc. 2005;62:71-75. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 83. | Mensink PB, Haringsma J, Kucharzik T, Cellier C, Pérez-Cuadrado E, Mönkemüller K, Gasbarrini A, Kaffes AJ, Nakamura K, Yen HH. Complications of double balloon enteroscopy: a multicenter survey. Endoscopy. 2007;39:613-615. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 261] [Cited by in RCA: 241] [Article Influence: 13.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 84. | Gerson LB, Tokar J, Chiorean M, Lo S, Decker GA, Cave D, Bouhaidar D, Mishkin D, Dye C, Haluszka O. Complications associated with double balloon enteroscopy at nine US centers. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009;7:1177-1182, 1177-1182. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 100] [Cited by in RCA: 112] [Article Influence: 7.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 85. | May A, Färber M, Aschmoneit I, Pohl J, Manner H, Lotterer E, Möschler O, Kunz J, Gossner L, Mönkemüller K. Prospective multicenter trial comparing push-and-pull enteroscopy with the single- and double-balloon techniques in patients with small-bowel disorders. Am J Gastroenterol. 2010;105:575-581. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 148] [Cited by in RCA: 152] [Article Influence: 10.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 86. | Takano N, Yamada A, Watabe H, Togo G, Yamaji Y, Yoshida H, Kawabe T, Omata M, Koike K. Single-balloon versus double-balloon endoscopy for achieving total enteroscopy: a randomized, controlled trial. Gastrointest Endosc. 2011;73:734-739. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 126] [Cited by in RCA: 130] [Article Influence: 9.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 87. | Domagk D, Mensink P, Aktas H, Lenz P, Meister T, Luegering A, Ullerich H, Aabakken L, Heinecke A, Domschke W. Single- vs. double-balloon enteroscopy in small-bowel diagnostics: a randomized multicenter trial. Endoscopy. 2011;43:472-476. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 126] [Cited by in RCA: 130] [Article Influence: 9.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 88. | Efthymiou M, Desmond PV, Brown G, La Nauze R, Kaffes A, Chua TJ, Taylor AC. SINGLE-01: a randomized, controlled trial comparing the efficacy and depth of insertion of single- and double-balloon enteroscopy by using a novel method to determine insertion depth. Gastrointest Endosc. 2012;76:972-980. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 52] [Cited by in RCA: 65] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 89. | Pai RD, Carr-Locke DL, Thompson CC. Endoscopic evaluation of the defunctionalized stomach by using ShapeLock technology (with video). Gastrointest Endosc. 2007;66:578-581. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 90. | Kuga R, Furuya CK, Hondo FY, Ide E, Ishioka S, Sakai P. ERCP using double-balloon enteroscopy in patients with Roux-en-Y anatomy. Dig Dis. 2008;26:330-335. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 91. | Rex DK, Khashab M, Raju GS, Pasricha J, Kozarek R. Insertability and safety of a shape-locking device for colonoscopy. Am J Gastroenterol. 2005;100:817-820. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 92. | Haber GWL. A prospective study to evaluate the ShapeLock guide to enable complete colonoscopy in previously failed cases. Gastrointest Endosc. 2006;63:AB226. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 93. | Schulz HJ, Schmidt H. Intraoperative enteroscopy. Gastrointest Endosc Clin N Am. 2009;19:371-379. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 94. | Douard R, Wind P, Berger A, Maniere T, Landi B, Cellier C, Cugnenc PH. Role of intraoperative enteroscopy in the management of obscure gastointestinal bleeding at the time of video-capsule endoscopy. Am J Surg. 2009;198:6-11. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 95. | Zaman A, Sheppard B, Katon RM. Total peroral intraoperative enteroscopy for obscure GI bleeding using a dedicated push enteroscope: diagnostic yield and patient outcome. Gastrointest Endosc. 1999;50:506-510. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 76] [Cited by in RCA: 66] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 96. | Lewis MP, Khoo DE, Spencer J. Value of laparotomy in the diagnosis of obscure gastrointestinal haemorrhage. Gut. 1995;37:187-190. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 97. | Douard R, Wind P, Panis Y, Marteau P, Bouhnik Y, Cellier C, Cugnenc P, Valleur P. Intraoperative enteroscopy for diagnosis and management of unexplained gastrointestinal bleeding. Am J Surg. 2000;180:181-184. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 89] [Cited by in RCA: 78] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 98. | Kovacs TO, Jensen DM. Recent advances in the endoscopic diagnosis and therapy of upper gastrointestinal, small intestinal, and colonic bleeding. Med Clin North Am. 2002;86:1319-1356. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 51] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 99. | Apostolopoulos P, Liatsos C, Gralnek IM, Kalantzis C, Giannakoulopoulou E, Alexandrakis G, Tsibouris P, Kalafatis E, Kalantzis N. Evaluation of capsule endoscopy in active, mild-to-moderate, overt, obscure GI bleeding. Gastrointest Endosc. 2007;66:1174-1181. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 64] [Cited by in RCA: 60] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 100. | Cellier C. Obscure gastrointestinal bleeding: role of videocapsule and double-balloon enteroscopy. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. 2008;22:329-340. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 101. | Somsouk M, Gralnek IM, Inadomi JM. Management of obscure occult gastrointestinal bleeding: a cost-minimization analysis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;6:661-670. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 43] [Cited by in RCA: 48] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 102. | Albert JG, Nachtigall F, Wiedbrauck F, Dollinger MM, Gittinger FS, Hollerbach S, Wienke A. Minimizing procedural cost in diagnosing small bowel bleeding: comparison of a strategy based on initial capsule endoscopy versus initial double-balloon enteroscopy. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2010;22:679-688. [PubMed] |

| 103. | Viazis N, Papaxoinis K, Vlachogiannakos J, Efthymiou A, Theodoropoulos I, Karamanolis DG. Is there a role for second-look capsule endoscopy in patients with obscure GI bleeding after a nondiagnostic first test? Gastrointest Endosc. 2009;69:850-856. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 76] [Cited by in RCA: 71] [Article Influence: 4.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 104. | Bar-Meir S. Video capsule endoscopy or double-balloon enteroscopy: are they equivalent? Gastrointest Endosc. 2009;69:875-876. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 105. | Kaffes AJ, Siah C, Koo JH. Clinical outcomes after double-balloon enteroscopy in patients with obscure GI bleeding and a positive capsule endoscopy. Gastrointest Endosc. 2007;66:304-309. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 77] [Cited by in RCA: 81] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 106. | González-Galilea A, Gálvez-Calderón C, García Sánchez V, de Dios-Vega J. F. Hemorragia digestiva de origen oscuro. Orientación diagnóstica y terapóutica. Publicacién electrónica. Available from: http: //www.sapd.es/revista/article.php?file=vol34_n1/03. |

| 107. | van Cutsem E, Rutgeerts P, Vantrappen G. Treatment of bleeding gastrointestinal vascular malformations with oestrogen-progesterone. Lancet. 1990;335:953-955. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 192] [Cited by in RCA: 172] [Article Influence: 4.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 108. | Barkin JS, Ross BS. Medical therapy for chronic gastrointestinal bleeding of obscure origin. Am J Gastroenterol. 1998;93:1250-1254. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 76] [Cited by in RCA: 64] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (3)] |

| 109. | Junquera F, Feu F, Papo M, Videla S, Armengol JR, Bordas JM, Saperas E, Piqué JM, Malagelada JR. A multicenter, randomized, clinical trial of hormonal therapy in the prevention of rebleeding from gastrointestinal angiodysplasia. Gastroenterology. 2001;121:1073-1079. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 189] [Cited by in RCA: 160] [Article Influence: 6.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 110. | Blich M, Fruchter O, Edelstein S, Edoute Y. Somatostatin therapy ameliorates chronic and refractory gastrointestinal bleeding caused by diffuse angiodysplasia in a patient on anticoagulation therapy. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2003;38:801-803. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 111. | Rossini FP, Arrigoni A, Pennazio M. Octreotide in the treatment of bleeding due to angiodysplasia of the small intestine. Am J Gastroenterol. 1993;88:1424-1427. [PubMed] |

| 112. | Bauditz J, Wedel S, Lochs H. Thalidomide reduces tumour necrosis factor alpha and interleukin 12 production in patients with chronic active Crohn’s disease. Gut. 2002;50:196-200. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 91] [Cited by in RCA: 107] [Article Influence: 4.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 113. | Krikis N, Tziomalos K, Perifanis V, Vakalopoulou S, Karagiannis A, Garipidou V, Harsoulis F. Treatment of recurrent gastrointestinal haemorrhage in a patient with von Willebrand’s disease with octreotide LAR and propranolol. Gut. 2005;54:171-172. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 114. | Molina-Infante J, Perez-Gallardo B, Gonzalez-Garcia G, Fernandez-Bermejo M, Mateos-Rodriguez JM, Robledo-Andres P. Octreotide LAR for severe obscure-overt gastrointestinal haemorrhage in high-risk patients on anticoagulation therapy. Gut. 2007;56:447. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 115. | Bon C, Aparicio T, Vincent M, Mavros M, Bejou B, Raynaud JJ, Zampeli E, Airinei G, Sautereau D, Benamouzig R. Long-acting somatostatin analogues decrease blood transfusion requirements in patients with refractory gastrointestinal bleeding associated with angiodysplasia. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2012;36:587-593. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 70] [Cited by in RCA: 62] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 116. | Ge ZZ, Chen HM, Gao YJ, Liu WZ, Xu CH, Tan HH, Chen HY, Wei W, Fang JY, Xiao SD. Efficacy of thalidomide for refractory gastrointestinal bleeding from vascular malformation. Gastroenterology. 2011;141:1629-37.e1-4. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 137] [Cited by in RCA: 167] [Article Influence: 11.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |