Published online Dec 15, 2012. doi: 10.4291/wjgp.v3.i6.102

Revised: November 16, 2012

Accepted: December 6, 2012

Published online: December 15, 2012

AIM: To investigate interleukin-6 (IL-6), mast cells, enterochromaffin cells, 5-hydroxytryptamine, and substance P in the gastrointestinal mucosa of children with abdominal pain.

METHODS: Formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded gastrointestinal biopsy blocks from patients (n = 48) with non-inflammatory bowel disease (irritable bowel syndrome and functional abdominal pain) and inflammatory bowel disease were sectioned and stained for IL-6, mast cells, enterochromaffin cells, 5-hydroxytryptamine, and substance P. All children had chronic abdominal pain as part of their presenting symptoms. Biopsy phenotype was confirmed by a pathologist, blinded to patient information. Descriptive statistics, chi-square, and independent sample t tests were used to compare differences between the inflammatory and non-inflammatory groups.

RESULTS: The cohort (n = 48), mean age 11.9 years (SD = 2.9), 54.2% females, 90% Caucasian, was comprised of a non-inflammatory (n = 26) and an inflammatory (n = 22) phenotype. There was a significant negative correlation between substance P expression and mast cell count (P = 0.05, r = -0.373). Substance P was found to be expressed more often in female patient biopsies and more intensely in the upper gastrointestinal mucosa as compared to the lower mucosa. There were significantly increased gastrointestinal mucosal immunoreactivity to IL-6 (P = 0.004) in the inflammatory phenotype compared to non-inflammatory. Additionally, we found significantly increased mast cells (P = 0.049) in the mucosa of the non-inflammatory phenotype compared to the inflammatory group. This difference was particularly noted in the lower colon biopsies.

CONCLUSION: The findings of this study yield preliminary evidence in identifying biomarkers of undiagnosed abdominal pain in children and may suggest candidate genes for future evaluation.

- Citation: Henderson WA, Shankar R, Taylor TJ, Del Valle-Pinero AY, Kleiner DE, Kim KH, Youssef NN. Inverse relationship of interleukin-6 and mast cells in children with inflammatory and non-inflammatory abdominal pain phenotypes. World J Gastrointest Pathophysiol 2012; 3(6): 102-108

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2150-5330/full/v3/i6/102.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4291/wjgp.v3.i6.102

Functional abdominal pain of non-inflammatory origin is reported in 10%-30% of children ranging from age 4-16 years[1,2]. Many children are on multiple therapies to alleviate abdominal pain which is a major cause of morbidity in children[3]. The gastrointestinal pathology in the spectrum of abdominal pain disorders ranging from functional gastrointestinal disorders (FGID) including irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) and functional abdominal pain to inflammatory bowel disease is poorly understood in children. The majority of children with FGIDs have no structural or biochemical evidence pointing towards their symptoms[4]. However, many patients with no evidence of inflammation on histology are not properly diagnosed[5] and continue to have abdominal pain suggesting a possible process that may not be visible microscopically[6]. Dysregulation of inflammatory markers (i.e., cytokines) and gut hormones demarcate the inflammatory bowel from the non-inflammatory one[7].

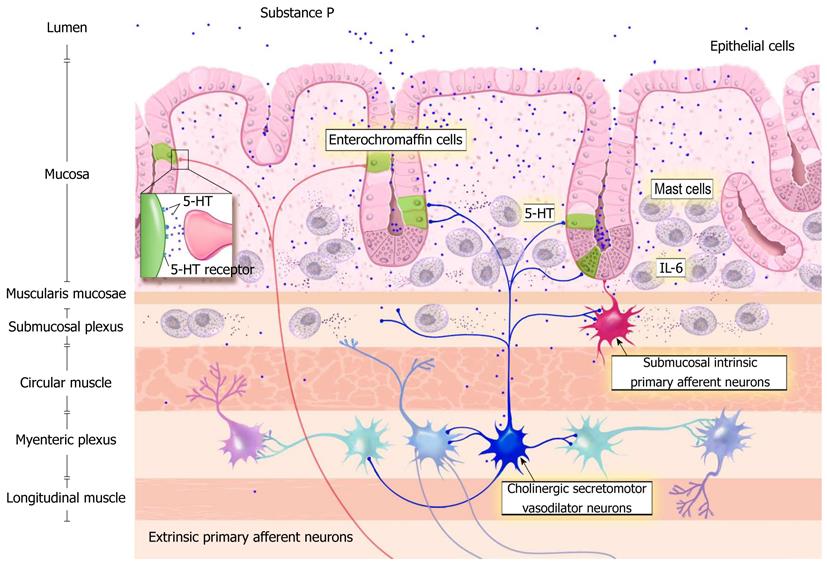

The roles of interleukin-6 (IL-6), mast cells, enterochromaffin cells (EC) and serotonin [also known as 5-hydroxytryptamine (5-HT)] are increasingly being recognized as important in the development of pain in chronic gastrointestinal (GI) disorders[6,8]. Intestinal mast cells and EC are identified as candidates in IBS symptomatology due to their release of immune and inflammatory mediators altering both nerve and muscle function[9-11]. A relationship between functional abdominal pain and increased mast cells in gastrointestinal mucosa of children has recently been reported[8]. The relationship of perceived visceral sensitivity (brain gut connection) is cited demonstrating the important role that 5-HT plays in possible disease progression and symptom severity[12-14]. Recent studies have also mentioned the possible role of mast cells and potential effect of degranulation on patient symptomatology including abdominal pain and bowel motility[15]. Substance P increases colonic propulsive movement and stimulates smooth muscles. Together with mast cells, substance P may be involved with the stimulation of the enteric nervous system thereby yielding abdominal pain. We hypothesize that there is an interaction of gut mucosa in children and inflammatory markers with local effects of substance P and 5-HT yielding increased secretory activity, luminal hypersensitivity, and sensory signaling. The neurodigestive mechanisms underlying this hypothesis are depicted in Figure 1.

The purpose of this study was to compare the levels of IL-6, mast cells, EC, 5-HT, and substance P in the gastrointestinal mucosa of children with chronic abdominal pain with and without evidence of inflammatory gastrointestinal disease. The a priori hypothesis being that there may be a subclinical underlying inflammatory biomarker related to abdominal pain.

This cohort study was comprised of pediatric patients with a history of chronic abdominal pain. Samples and data from children with chronic abdominal pain were collected from the Goryeb Children’s Hospital, Morristown, New Jersey. The study was approved by both the Institutional Review Board of the Goryeb Children’s Hospital, Atlantic Health (#R07-09-009) and the Office of Human Subjects Research at the National Institutes of Health (OHSR#3906). This study involved the use of existing samples and data/medical records which were recorded by the investigating team in a manner that subjects were not able to be directly identified.

The sample pool included patients with a history of FGID (chronic abdominal pain, irritable bowel syndrome) and patients with a diagnosis of inflammatory bowel disease. All patients in this study had an outpatient and an endoscopic evaluation. Prior to immunohistochemistry measures, hematoxylin and eosin stained slides were evaluated by a trained pathologist (blinded to patient information or diagnosis) to reconfirm the patient phenotype noted in the medical record.

Demographic variables (age, sex and race) and pertinent medical history (diagnosis, pain scores, treatment history, family history, anthropometric measures, co-morbid conditions, biopsy location) were extracted. Demographic variables were categorized as follows; age (years), sex (male/female) and race (Caucasian/African-American/Asian/Mixed/Hispanic).

Formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded blocks of colonic tissue were also obtained (upper GI sections = 15, lower GI sections = 33). Biopsies were sectioned at 7 micron thickness and stained for mast cells, EC cells, IL-6, substance P and 5-HT.

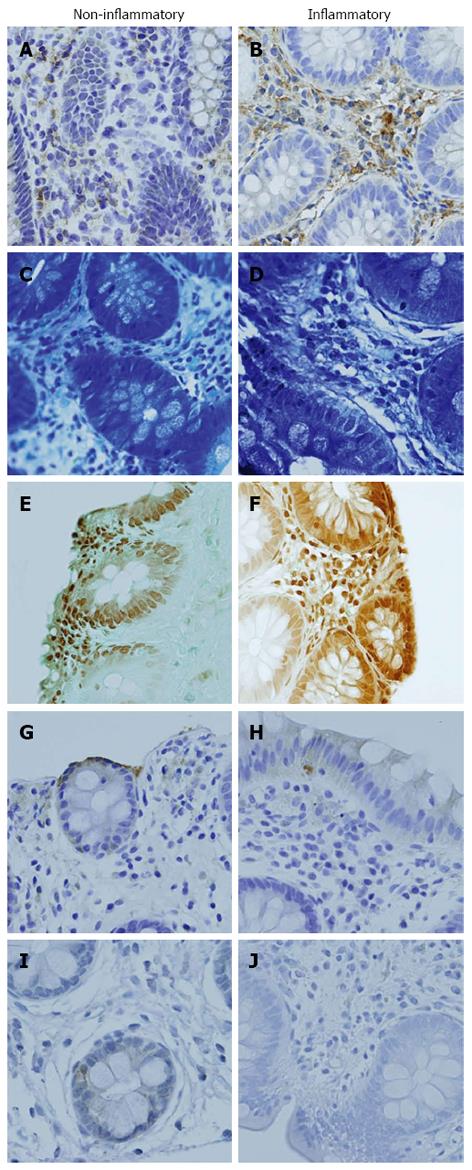

Immunohistochemical staining techniques were used to identify immunoreactivity for the biomarkers IL-6 and 5-HT. All staining was achieved using Vision Biosystems’ BondMax autostainer (Leica Microsystems Inc., Bannockburn, IL) and performed at the National Cancer Institute, Science Applications International Corporation in Frederick, Maryland. For IL-6, paraffin-embedded gastrointestinal sections (7 microns) were deparaffinized and incubated for 20 min with 2% normal goat serum (Vector Labs Inc., Burlingame, CA) followed by incubation for 30 min at room temperature using primary antibody IL-6 (diluted 1:400 in Vision Biosystems’ Ab diluent). A 30 min incubation of biotinylated goat anti-rabbit IgG, (Vector Labs Inc., Burlingame, CA) followed this. Human spleen and tonsils tissues were used as positive controls. IL-6 levels were analyzed and graded by a pathologist and recorded as minimal, mild, moderate, or marked. (Figure 2A and B)

Mast cells were stained in deparaffinized 7 micron gastrointestinal tissue with toluidine blue for two minutes then rinsed. The tissue was then dehydrated in acetone for two minutes twice and cleared in xylene prior to mounting. Mast cells were counted as number of mast cells per 40x high power field (HPF) for 10 consecutive fields and then averaged by a trained technician or pathologist (Figure 2C and D).

EC cells were identified with silver stain (Grimelius-Argyrophil). Then the number of EC cells were counted per HPF 40x and categorized as minimal (1-2 cells), mild (3-5 cells), moderate (6-10 cells), or marked (≥ 16 cells) by a pathologist (Figure 2E and F).

Similarly, for 5-HT, deparaffinized 7 micron gastrointestinal tissue was incubated for 20 min with 2% normal horse serum (Vector Labs Inc., Burlingame, CA) followed by incubation for 30 min at room temperature using a 5-HT primary antibody (diluted 1:40 in Vision Biosystems’ Ab diluent). A 30 min incubation of biotinylated horse anti-mouse IgG, (Vector Labs Inc., Burlingame, CA) followed this. Human colon tissues were used as positive control. Both methods were followed by staining with streptavidin horse radish peroxidase, then diaminobenzidine. Hematoxylin was used for counterstaining of the slides. 5-HT levels were graded by a pathologist and recorded as minimal, mild, moderate, or marked (Figure 2G and H).

Mouse monoclonal antibody [SP-DEA-21] (ab14184), specific to the detection of human substance P was utilized. Human fetal spinal cord was used as the control. Substance P levels were graded as positive or negative staining for presence of substance P (Figure 2I and J).

Descriptive statistics, chi square analysis, correlations, independent sample t tests were performed to compare differences between the inflammatory and non-inflammatory phenotypic groups. A P value of < 0.05 was used to determine statistical significance a priori. SPSS© version 15 software (Chicago, IL) was used for statistical analysis.

The sample size of 48 patients with abdominal pain was divided into those with and without inflammation based on the blinded pathologists’ evaluation. The overall cohort was comprised of patients ranging from 5 to 17 years (mean age 11.9 years, SD = 2.9), 54.2% female, 89.6% Caucasian, body mass index (BMI) ranging from 13 to 38.8 kg/m2 (mean 18.9, SD = 4.3). In addition, 24 of the subjects were lactose intolerant.

The non-inflammatory group comprised of 26 patients, age ranging from 8 to 16 years (mean 11.9 years, SD = 2.4), 57.7% female, 88.5% Caucasian, BMI ranging from 13.8 to 38.8 kg/m2 (mean 19.5, SD = 5.2) with 16 patients being lactose intolerant. The inflammatory group comprised of 22 patients, age ranging from 5 to 17 years (mean 12 years, SD = 3.5), 50% female, 90.9% Caucasian, BMI ranging from 13 to 24.5 kg/m2 (mean 18.2, SD = 2.8) with 8 patients being lactose intolerant. There were no statistically significant differences between those with and without inflammation with respect to sex, race, age, BMI, or lactose intolerance (Table 1). There were no differences in the groups with regard to abdominal pain reports.

| Variable | Overall(n = 48) | Group | P value (χ2/t) | |

| Non inflammatory(n = 26) | Inflammatory (n = 22) | |||

| Sex | ||||

| Male | 22 (45.8) | 11 (42.3) | 11 (50) | 0.59 |

| Female | 26 (54.2) | 15 (57.7) | 11 (50) | |

| Race | ||||

| Caucasian | 43 (89.6) | 23 (88.5) | 20 (90.9) | 0.58 |

| Asian | 2 (4.2) | 1 (3.8) | 1 (4.5) | |

| African American | 1 (2.1) | 1 (3.8) | 0 (0) | |

| Mixed | 1 (2.1) | 0 (0) | 1 (4.5) | |

| Hispanic | 1 (2.1) | 1 (3.8) | 0 (0) | |

| Age (mean ± SD) | 11.9 ± 2.9 | 11.9 ± 2.4 | 12 ± 3.5 | 0.21 |

| range (yr) | (5-17) | (8-16) | (5-17) | |

| BMI (mean ± SD) | 18.9 ± 4.3 | 19.5 ± 5.2 | 18.2 ± 2.8 | 0.43 |

| range | (13-38.8) | (13.8-38.8) | (13-24.5) | |

| Diagnosis | ||||

| RAP | 17 (35.4) | 17 | ||

| IBS | 8 (16.6) | 8 | ||

| Crohn’s disease | 12 (25) | 12 | ||

| Ulcerative colitis | 8 (16.6) | 8 | ||

| Gastritis | 2 (4.1) | 2 | ||

| Location of biopsy | ||||

| Upper | 15 (31.3) | 12 (46.2) | 3 (13.6) | |

| Lower | 33 (68.8) | 14 (53.8) | 19 (86.4) | |

| Lactose intolerance | ||||

| Yes | 24 | 16 | 8 | 0.38 |

| No | 24 | 10 | 14 | |

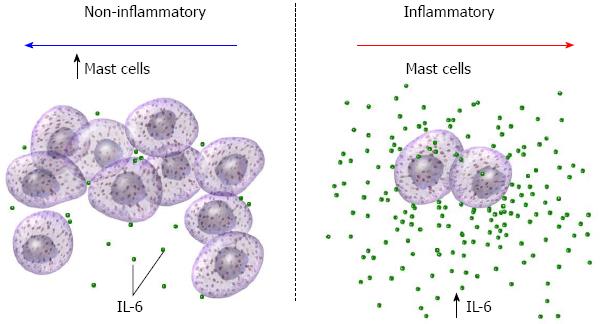

Expression of IL-6 (Figure 2A and B), 5-HT (Figure 2G and H) and substance P (Figure 2I and J) were studied using immunohistochemistry, and mast cells (Figure 2C and D) and EC cells (Figure 2E and F) were quantified. Overall, there was a statistical difference in mast cell count (P = 0.049) and levels of IL-6 expression (P = 0.004) between those with and without inflammation (Figure 3). There was no statistically significant difference in EC count or levels of 5-HT levels in patients with and without inflammation (Table 2). Data were analyzed further after subcategorization based on location of biopsy (upper/lower). There was a significant difference in mast cell count (P = 0.01) and levels of IL-6 expression (P = 0.004) in those with and without inflammation in lower biopsies. Compared to those without inflammation, patients with inflammation were more likely have higher IL-6 levels (1.50 ± 0.65 vs 2.35 ± 0.61) whereas those without inflammation were more likely to have a higher count of mast cells (5.00 ± 2.99 vs 2.88 ± 1.86). There was no statistically significant difference among those with and without inflammation for any markers in the upper biopsies.

| Group | P value | ||

| Non inflammatory(n = 26) | Inflammatory(n = 22) | ||

| Interleukin-6 | 1.50 ± 0.65 | 2.35 ± 0.61 | 0.004 |

| Mast cells (HPF) | 3.54 ± 2.92 | 2.63 ± 1.83 | 0.049 |

| Enterochromaffin cells | 1.95 ± 0.81 | 1.84 ± 0.69 | 0.81 |

| 5-hydroxytryptamine | 1.14 ± 0.64 | 1.05 ± 0.39 | 0.18 |

| Substance P, % stained (ratio +/-) | 69.23% (18/26) | 45.45% (10/22) | 0.49 |

Substance P was found to be increased and multifocal within the epithelial GI mucosa in patients with chronic abdominal pain in the non-inflammatory phenotype. Interestingly, substance P was found predominately in the superficial layers of the non-inflammatory mucosa. Substance P positive staining was found in 28 patients. There was no statistical difference in the groups with regard to presence of substance P. Comparatively; substance P staining was found to be increased and multifocal within the gastrointestinal mucosa in patients with chronic abdominal pain with a trend toward increased expression in non-inflammatory female patient biopsies. There was a significant negative correlation between substance P expression and mast cell count (P = 0.05, r = -0.373). There was a significant positive correlation between substance P and 5-HT in females (P = 0.037, r = 0.447), but not in males (P = 0.28, r = 0.252). Substance P was found to be expressed more often in female patient biopsies and expressed more intensely in the upper GI mucosa as compared to the lower GI mucosa.

The findings of this study highlight a molecular difference in the subclinical gastrointestinal pathology of abdominal pain disorders, specifically further evidence of the involvement of substance P and mast cells in pediatric functional gastrointestinal disorders distinct from inflammatory gastrointestinal disorders (Figure 3). This is a novel finding of substance P in the superficial layers of the non-inflammatory mucosa. These findings support existing literature in other painful syndromes including complex regional pain syndrome type 1[16]. Substance P alterations may underlie neurological and psychiatric disorders, including pain perception, obesity, and depression. Furthermore, substance P may potentiate the effects of mast cell maturation and degranulation further contributing to neuronal stimulation. The product of this complex interplay of molecules may result in hypersensitivity. Mast cell degranulation may activate a gastrointestinal pain pathway similar to migraine headaches[7,17].

5-HT is widely known to exist within the gastrointestinal tract localized to digestive enterochromaffin cells and enteric neuronal communicating branches. Local effects of 5-HT include increased secretory activity, peristalsis, luminal hypersensitivity, and sensory signaling. 5-HT receptors are present on the terminals of both enteric and extrinsic sensory neurons and relay messages related to the lumen and chemical environment to enteric interneurons and ultimately to sensory centers within the central nervous system. Potentiating the effects, mast cell maturation and degranulation contribute to further neuronal stimulation as well as local effects by mediators such as histamine and interleukin-6. The product of this complex interplay of molecules results in baseline inflammation and colonic hypersensitivity (Figure 1).

Limitations of this study include the small sample size and the analysis of existing clinical samples. An additional limitation is the use of an inflammatory control group rather than a normal control group. However, pediatric endoscopy without cause or symptom is ethically unwarranted due to lack of benefit related to an unnecessary procedure with risks. The pediatric biopsies included in the non-inflammatory phenotypic group were from non-specific phenotypes of functional GI disorders involving abdominal pain as a presentation. There was no significant difference in abdominal pain perceptions between the inflammatory and non-inflammatory phenotypes. The biopsies were obtained from pediatric patients with a standard bowel preparation which has been linked to pro-inflammatory effects[18]. However, all the patients were from the same institution and received the same bowel preparation. Given the aforementioned limitations, statistically significant differences were found between inflammatory and non-inflammatory phenotypes, in that the pediatric patient biopsies with known inflammatory bowel disease were used as the comparison group. The elevation in IL-6 in the inflammatory group was expected. What was unexpected was the discovery of elevated mast cell count in the non-inflammatory phenotypic group and in the same phenotype positive staining for substance P in biopsies from females.

Future prospective studies are needed to more fully investigate the role of substance P and mast cells in children with chronic abdominal pain. Identification of biomarkers to help differentiate phenotypes of chronic abdominal pain in the pediatric population is needed to improve assessment and develop novel treatments. The role of substance P and mast cells is an area that needs to be further investigated. These studies may include proximity of the mast cells to the nerves as demonstrated in an adult cohort[19] prospectively while differentiating functional phenotypes.

The authors thank Dr. Miriam Anver, Ms. Donna Butcher, and Dr. Mones Abu-Asab for immunohistochemical support and Ms. Annette Langseder for clinical support.

The gastrointestinal pathology in the spectrum of abdominal pain disorders ranging from irritable bowel syndrome to inflammatory bowel disease is poorly understood, particularly in children. The aims of this study were to compare the expression of interleukin-6 (IL-6), mast cells, enterochromaffin cells, 5-hydroxytryptamine, and substance P in the gastrointestinal mucosa biopsies of children with chronic abdominal pain with and without evidence of inflammatory gastrointestinal disease.

The findings of this study highlight a molecular difference in the subclinical gastrointestinal pathology of abdominal pain disorders, specifically further evidence of the involvement of mast cells and substance P in pediatric functional gastrointestinal disorders distinct from inflammatory gastrointestinal disorders.

The present study showed novel findings including the inverse relationship of IL-6 and substance P with mast cells. In addition, the discovery of elevated mast cell count in the non-inflammatory phenotypic group and in the same phenotype positive staining for substance P in biopsies from females.

The findings from the present data stress the need for identification of clear biomarkers to advance evaluation and treatment of patients with abdominal pain symptoms. Further, this study yields preliminary evidence in identifying biomarkers of abdominal pain in children and may further suggest candidate genes for future evaluation.

The study offers greater insight into biomarkers associated with chronic abdominal pain that were previously termed functional gastrointestinal disorders.

Peer reviewer: Niels Olsen Saraiva Câmara, Associate Professor of Immunology, Department of Immunology, Universidade de São Paulo, Rua Leandro Dupret 488/52, Vila Clementino 04025-012, São Paulo, SP, Brazil

S- Editor Zhai HH L- Editor A E- Editor Zhang DN

| 1. | Boyle JT. Recurrent abdominal pain: an update. Pediatr Rev. 1997;18:310-20; quiz 321. [PubMed] |

| 2. | Schwille IJ, Giel KE, Ellert U, Zipfel S, Enck P. A community-based survey of abdominal pain prevalence, characteristics, and health care use among children. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009;7:1062-1068. [PubMed] |

| 3. | Youssef NN, Atienza K, Langseder AL, Strauss RS. Chronic abdominal pain and depressive symptoms: analysis of the national longitudinal study of adolescent health. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;6:329-332. [PubMed] |

| 4. | Halder SL, Locke GR, Schleck CD, Zinsmeister AR, Melton LJ, Talley NJ. Natural history of functional gastrointestinal disorders: a 12-year longitudinal population-based study. Gastroenterology. 2007;133:799-807. [PubMed] |

| 5. | Spiegel BM, Farid M, Esrailian E, Talley J, Chang L. Is irritable bowel syndrome a diagnosis of exclusion?: a survey of primary care providers, gastroenterologists, and IBS experts. Am J Gastroenterol. 2010;105:848-858. [PubMed] |

| 6. | Mahjoub FE, Farahmand F, Pourpak Z, Asefi H, Amini Z. Mast cell gastritis: children complaining of chronic abdominal pain with histologically normal gastric mucosal biopsies except for increase in mast cells, proposing a new entity. Diagn Pathol. 2009;4:34. [PubMed] |

| 7. | Zhang XC, Strassman AM, Burstein R, Levy D. Sensitization and activation of intracranial meningeal nociceptors by mast cell mediators. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2007;322:806-812. [PubMed] |

| 8. | Taylor TJ, Youssef NN, Shankar R, Kleiner DE, Henderson WA. The association of mast cells and serotonin in children with chronic abdominal pain of unknown etiology. BMC Res Notes. 2010;3:265. [PubMed] |

| 9. | Castro GA, Harari Y, Russell D. Mediators of anaphylaxis-induced ion transport changes in small intestine. Am J Physiol. 1987;253:G540-G548. [PubMed] |

| 10. | Piche T, Saint-Paul MC, Dainese R, Marine-Barjoan E, Iannelli A, Montoya ML, Peyron JF, Czerucka D, Cherikh F, Filippi J. Mast cells and cellularity of the colonic mucosa correlated with fatigue and depression in irritable bowel syndrome. Gut. 2008;57:468-473. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 142] [Cited by in RCA: 148] [Article Influence: 8.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Vermillion DL, Ernst PB, Scicchitano R, Collins SM. Antigen-induced contraction of jejunal smooth muscle in the sensitized rat. Am J Physiol. 1988;255:G701-G708. [PubMed] |

| 12. | Gershon MD. Review article: roles played by 5-hydroxytryptamine in the physiology of the bowel. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 1999;13 Suppl 2:15-30. [PubMed] |

| 13. | Humphrey PP, Bountra C, Clayton N, Kozlowski K. Review article: the therapeutic potential of 5-HT3 receptor antagonists in the treatment of irritable bowel syndrome. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 1999;13 Suppl 2:31-38. [PubMed] |

| 14. | Faure C, Patey N, Gauthier C, Brooks EM, Mawe GM. Serotonin signaling is altered in irritable bowel syndrome with diarrhea but not in functional dyspepsia in pediatric age patients. Gastroenterology. 2010;139:249-258. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 129] [Cited by in RCA: 116] [Article Influence: 7.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Gissen AJ, Covino BG, Gregus J. Differential sensitivities of mammalian nerve fibers to local anesthetic agents. Anesthesiology. 1980;53:467-474. [PubMed] |

| 16. | Huygen FJ, Ramdhani N, van Toorenenbergen A, Klein J, Zijlstra FJ. Mast cells are involved in inflammatory reactions during Complex Regional Pain Syndrome type 1. Immunol Lett. 2004;91:147-154. [PubMed] |

| 17. | Levy D, Burstein R, Kainz V, Jakubowski M, Strassman AM. Mast cell degranulation activates a pain pathway underlying migraine headache. Pain. 2007;130:166-176. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 309] [Cited by in RCA: 285] [Article Influence: 15.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Pockros PJ, Foroozan P. Golytely lavage versus a standard colonoscopy preparation. Effect on normal colonic mucosal histology. Gastroenterology. 1985;88:545-548. [PubMed] |

| 19. | Barbara G, Stanghellini V, De Giorgio R, Cremon C, Cottrell GS, Santini D, Pasquinelli G, Morselli-Labate AM, Grady EF, Bunnett NW. Activated mast cells in proximity to colonic nerves correlate with abdominal pain in irritable bowel syndrome. Gastroenterology. 2004;126:693-702. [PubMed] |