Published online May 22, 2021. doi: 10.4291/wjgp.v12.i3.40

Peer-review started: January 21, 2021

First decision: February 9, 2021

Revised: February 25, 2021

Accepted: March 31, 2021

Article in press: March 31, 2021

Published online: May 22, 2021

Processing time: 112 Days and 18.8 Hours

Simple tools for clinicians to identify cirrhosis in patients with chronic viral hepatitis are medically necessary for treatment initiation, hepatocellular cancer screening and additional medical management.

To determine whether platelets or other laboratory markers can be used as a simple method to identify the development of cirrhosis.

Clinical, biochemical and histologic laboratory data from treatment naive chronic viral hepatitis B (HBV), C (HCV), and D (HDV) patients at the NIH Clinical Center from 1985-2019 were collected and subjects were randomly divided into training and validation cohorts. Laboratory markers were tested for their ability to identify cirrhosis (Ishak ≥ 5) using receiver operating characteristic curves and an optimal cut-off was calculated within the training cohort. The final cut-off was tested within the validation cohort.

Overall, 1027 subjects (HCV = 701, HBV = 240 and HDV = 86), 66% male, with mean (standard deviation) age of 45 (11) years were evaluated. Within the training cohort (n = 715), platelets performed the best at identifying cirrhosis compared to other laboratory markers [Area Under the Receiver Operating Characteristics curve (AUROC) = 0.86 (0.82-0.90)] and sensitivity 77%, specificity 83%, positive predictive value 44%, and negative predictive value 95%. All other tested markers had AUROCs ≤ 0.77. The optimal platelet cut-off for detecting cirrhosis in the training cohort was 143 × 109/L and it performed equally well in the validation cohort (n = 312) [AUROC = 0.85 (0.76-0.94)].

The use of platelet counts should be considered to identify cirrhosis and ensure optimal care and management of patients with chronic viral hepatitis.

Core Tip: Platelet count is a well-recognized surrogate marker for progression of liver disease, however a specific cut-off for cirrhosis has not been established. In this study, platelet counts can accurately stratify chronic viral hepatitis patients with cirrhosis; and a platelet count > 143 × 109/L appears to have the most clinical utility in ruling out cirrhosis across all chronic viral hepatitis. This widely available laboratory value may be useful in decision making for the management of patients with chronic viral hepatitis and represents a finding which may be of particular value in a primary care setting.

- Citation: Surana P, Hercun J, Takyar V, Kleiner DE, Heller T, Koh C. Platelet count as a screening tool for compensated cirrhosis in chronic viral hepatitis. World J Gastrointest Pathophysiol 2021; 12(3): 40-50

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2150-5330/full/v12/i3/40.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4291/wjgp.v12.i3.40

Globally, chronic hepatitis B, C, and D virus (HBV, HCV and HDV respectively) affect about 325 million people[1]. Progression of these viral infections is associated with serious complications including cirrhosis, hepatic decompensation, hepatocellular carcinoma, and death. With effective treatments for hepatitis B and C, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention have advocated for widespread screening for viral hepatitis in adults[2,3]. There has also been a paradigm shift where primary care physicians are increasingly tasked with managing and treating these patients[4], and various programs have allowed for expanded care in areas with poor access to viral hepatitis care[5]. In addition, numerous efforts worldwide have aimed to increase the number of providers with the ability to manage chronic viral hepatitis, including the national viral hepatitis action plan 2017-2020 by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services[6] and the Mukh-Mantri Punjab Hepatitis C Relief Fund program in India[7].

The decision of when and whom to treat in chronic viral hepatitis infections is often dependent upon the stage of liver disease[8,9]. Currently, liver biopsy is the gold standard for staging disease severity in patients with liver disease. However, liver biopsies are invasive, performed by a specialist and access may be limited in resource-poor regions. To date, no single routinely measured laboratory marker has been explored for the identification of cirrhosis. Although expert consensus suggests that thrombocytopenia, with a laboratory cutoff value of < 150 × 109/L, is a surrogate marker for cirrhosis, this has mostly been demonstrated in patients with chronic HCV[10,11]. More recently, platelet counts have been used in conjunction with other markers. Current hepatology guidelines state that clinically significant portal hypertension can be identified by “liver stiffness > 20-25 kPa, alone or combined with platelet count and spleen size”[12]. Unfortunately, ultrasound-based techniques [such as Vibration Controlled Transient Elastography (VCTE)] providing an assessment of liver stiffness and cirrhosis are not widely available in all regions and to all healthcare providers.

Common serum laboratory tests, including platelet counts, have been included in non-invasive markers of liver fibrosis or cirrhosis and have demonstrated clinical utility in the management of hepatitis C[9,13]. However, these non-invasive markers have not been shown to be as useful in chronic HBV due to its complex natural history[14,15]. Nonetheless, these tools have provided a cost-effective method to identify disease progression in patients with chronic viral hepatitis. Unfortunately, these tests require an on-line calculator as well as interpretation of various cutoff values and although often used by hepatologists and gastroenterologists, they remain unknown to primary care providers. Additionally, while their use for diagnosis of advanced fibrosis is widespread, they are not as powerful in determining cirrhosis as ultrasound-based methods[16,17].

With the increasing role of primary care providers in the management of chronic viral hepatitis, the development of a widely available and versatile tool in identifying patients with cirrhosis is clinically necessary. In this group of patients, additional management and treatment considerations may be required, as well as a referral to a specialist. In this study, we explore whether platelets or other commonly measured laboratory markers, alone, can be used as a simple and effective way to characterize the progression of viral hepatitis and whether a threshold can be identified for the development of cirrhosis.

This retrospective, cross-sectional study consisted of patients infected with HBV, HCV or HDV and who underwent liver biopsy at the National Institutes of Health Clinical Center between 1985 and June 2019. Chronic viral hepatitis infection was established if patients demonstrated viral positivity for at least six months and/or histology consistent with the respective chronic infection. Chronic hepatitis B infection was established with the presence of hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg) in serum and positive HBsAg or hepatitis B core antigen staining on histology. Chronic hepatitis D co-infection was established with the presence of anti-HDV antibodies and HDV RNA in serum or positive hepatitis D antigen staining on histology in patients with chronic HBV. In patients who underwent biopsy after 1991, chronic hepatitis C was estab

Patients with concomitant chronic non-viral liver diseases, multiple viral hepatitis (besides HBV/HDV co-infection), or HIV co-infection were excluded. In addition, patients were judged to be in adequate overall health to undergo liver biopsy and had no severe systemic diseases. All patients were enrolled in clinical research protocols approved by the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases Institutional Review Board and gave written, informed consent for participation. Pre-treatment liver biopsies were reviewed, and concurrent laboratory values were also collected using the NIH Biomedical Translational Research Information System. Laboratory results within two months prior to the liver biopsy and initiation of any treatment were utilized for analysis.

All liver biopsies were scored and analyzed by a single hepatopathologist (DEK). Ishak fibrosis scores were used to score hepatic fibrosis, ranging from 0 (no fibrosis) to 6 (cirrhosis)[18]. Cirrhosis was defined as a score ≥ 5. Inflammation was scored using the modified histologic activity index (HAI), ranging from 0-18[19]. The total HAI score comprised of the summation of periportal inflammation, lobular inflammation, and portal inflammation.

Training and validation cohorts: The entire cohort was randomly divided into training and validation cohorts using simple random sampling and a sample rate of 0.3. Selection was stratified by gender and virus type. Univariate comparisons of the two cohorts were conducted using student t-tests and chi-square tests where appropriate. Based on this analysis the training and validation cohorts were similar.

Biomarker selection: The training cohort was used to single out the best performing biomarker to identify cirrhosis status. Spearman’s correlations were calculated in the training cohort to determine the association between fibrosis and selected laboratory markers. Of the significantly correlated laboratory parameters, those with an absolute value of Spearman’s R greater than 0.3 (moderate correlation) were selected for further analysis within the training cohort[20]. Logistic regression was used to create receiver operating curves and calculate the area under the curve (AUROC) of each selected laboratory parameter within the training cohort. Laboratory markers were log transformed to assure normality of the data. Sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value, and negative predictive value were also used to measure performance. Delong Test was used to compare ROC curves for different laboratory parameters within the same sample group. Youden’s index, as well as sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value, and negative predictive value were all used to determine the optimal platelet cut-off point to predict cirrhosis. Once this analysis was completed in the training cohort, the most significant factor in the training cohort was tested in the validation cohort and by virus within the validation cohort through AUROC values, sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value, and negative predictive value. Fibrosis-4 index (Fib-4) and AST (aspartate aminotransferase) to Platelet Ratio Index (APRI) were calculated using the established formulas[9,13]. All analysis was conduc

A total of 1027 untreated subjects with viral hepatitis were evaluated (HCV = 701, HBV = 240, HDV = 86). The mean age of the cohort was 45 years (SD: 11) and 66% of subjects were male. Baseline demographics for the training and validations cohort are displayed in Table 1. In the training cohort, the mean Ishak fibrosis score was 2.4 (SD: 1.8) and 15% of patients were cirrhotic.

| Training (n = 715) | Validation (n = 312) | P value | |

| Age (yr) | 45.6 (10.7) | 44.5 (11.1) | 0.1 |

| Male/female (%) | 66/34 | 66/34 | 1.0 |

| Platelets (× 109/L) | 186.7 (64.4) | 190.6 (68.2) | 0.4 |

| Alanine aminotransferase (IU/L) | 103.8 (88.1) | 105.1 (89.1) | 0.8 |

| Aspartate aminotransferase (IU/L) | 69.9 (55.0) | 68.0 (53.3) | 0.6 |

| Albumin (g/dL) | 3.9 (0.46) | 3.9 (0.39) | 0.2 |

| Alkaline phosphatase (IU/L) | 82.3 (39.2) | 79.0 (29.2) | 0.1 |

| Prothrombin time (s) | 13.0 (1.3) | 12.9 (1.1) | 0.3 |

| Total bilirubin (mg/dL) | 0.81 (0.48) | 0.77 (0.45) | 0.2 |

| Ishak fibrosis | 2.4 (1.8) | 2.3 (1.7) | 0.3 |

| HAI inflammation | 8.0 (3.0) | 7.9 (3.1) | 0.5 |

| HBV/HCV/HDV (%) | 23/68/8 | 23/68/9 | 1.0 |

Mean platelet count in the training cohort was 187 × 109/L (SD: 64). Mean alanine aminotransferase (ALT) and AST values were elevated within the training cohort [104 IU/mL (SD: 88); 70 IU/mL (SD: 55) respectively]. Mean albumin, prothrombin time, total bilirubin, and alkaline phosphatase values were within normal limits.

Laboratory markers commonly used to characterize liver disease were tested for their ability to identify cirrhosis within the training cohort (Table 2). These markers included transaminases, platelet count, total bilirubin, prothrombin time, albumin, and alkaline phosphatase. On Spearman’s correlation of the training cohort, all tested laboratory markers appeared to be significantly correlated with Ishak fibrosis stage; however, only platelets, ALT, AST, alkaline phosphatase, and prothrombin time had Spearman correlations > 0.3 (Table 2).

| R | P value | |

| Platelets | -0.49 | < 0.0001 |

| AST | 0.51 | < 0.0001 |

| ALT | 0.37 | < 0.0001 |

| Alkaline phosphatase | 0.35 | < 0.0001 |

| Prothrombin time | 0.33 | < 0.0001 |

| Albumin | -0.30 | < 0.0001 |

| Total bilirubin | 0.18 | < 0.0001 |

Out of all of these laboratory markers, platelets performed the best at identifying cirrhosis compared to other laboratory markers (AUROC = 0.86, 95%CI 0.82-0.90), with all other markers with AUROCs ≤ 0.77 (Table 3). Prothrombin time had the next highest AUROC in the entire cohort (0.76, 95%CI 0.71-0.82). When comparing the ROC curves by the Delong test, platelets performed significantly better than all other tested laboratory markers in the training cohort (P < 0.002). Platelet counts compared favorably to both APRI [AUROC 0.84 (95%CI 0.80-0.88)] and Fib-4 [AUROC 0.88 (95%CI 0.85-0.91)].

| Platelets | ALT | AST | Alkaline phosphatase | Prothrombin time |

| 0.86 (0.82, 0.90) | 0.65 (0.59, 0.71) | 0.76 (0.71, 0.81) | 0.76 (0.71, 0.81) | 0.77 (0.71, 0.82) |

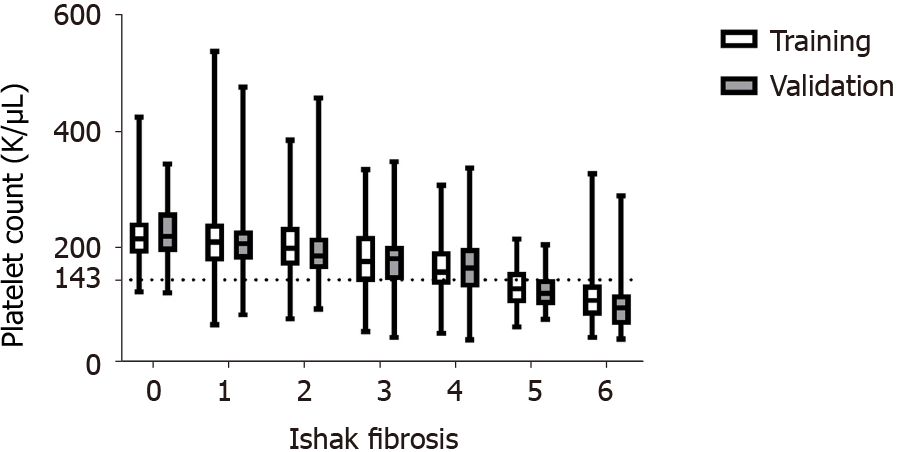

The optimized platelet cut-off for detecting cirrhosis in the training cohort was 143 × 109/L (sensitivity: 77%, specificity: 83%, positive predictive value: 44%, negative predictive value: 95%). Figure 1 shows an overall decrease in the distribution of platelet count by Ishak fibrosis in the training and validation cohorts. Additionally, the demarcated, calculated platelet cut-off of 143 × 109/L appears to separate a majority of subjects with Ishak fibrosis ≥ 5 (Figure 1).

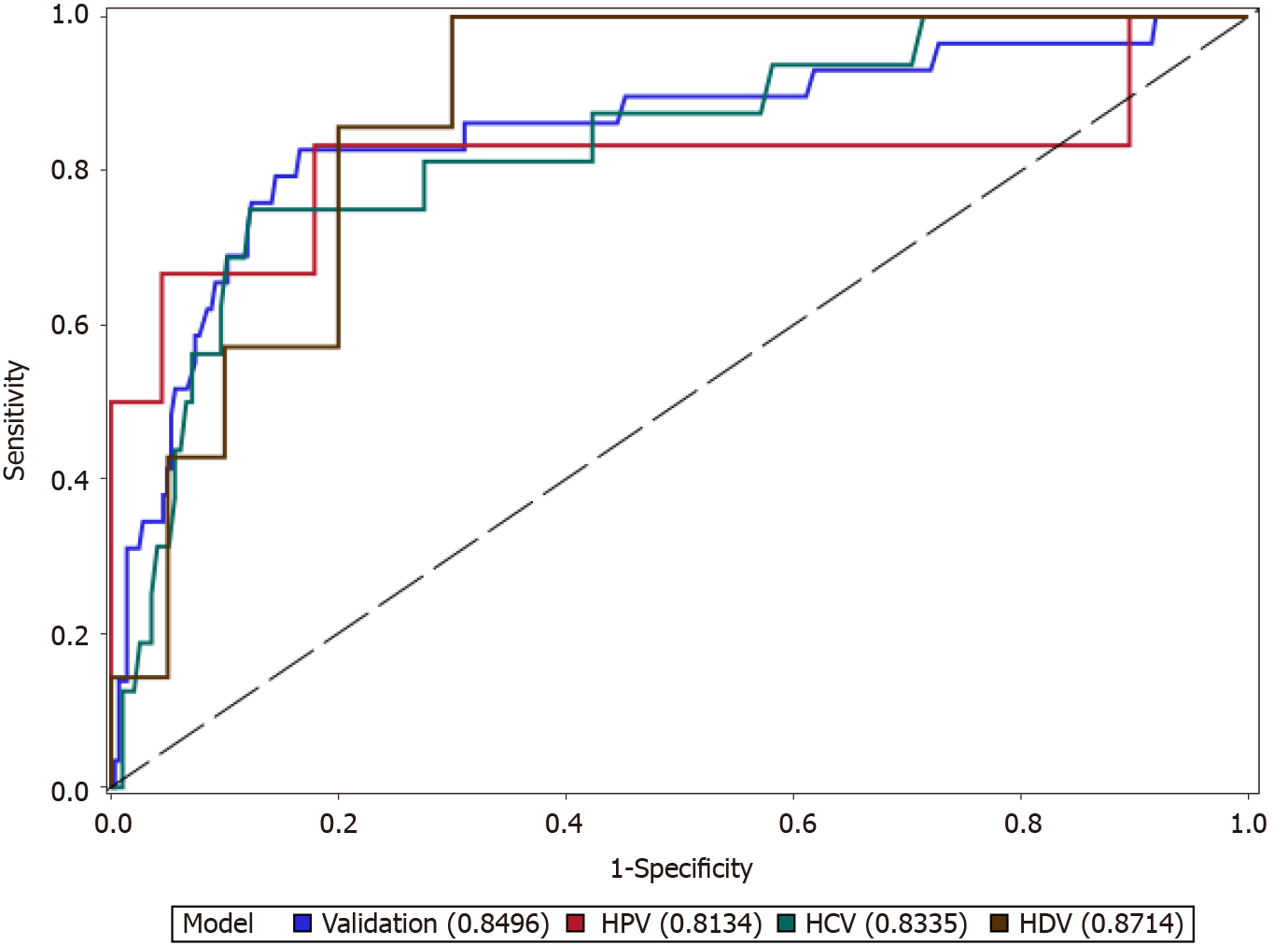

The cutoff calculated in the training cohort was applied to the entire validation cohort and was also evaluated for each viral hepatitis. The performance of platelets to identify cirrhosis is demonstrated in Figure 2; platelets performed adequately in each virus (AUROC ≥ 0.81) and performed best in the HDV/HBV co-infection subset of the validation cohort (AUROC = 0.87). In the entire validation cohort, platelets performed with an AUROC of 0.85 (95%CI 0.76-0.94) and performed as well as APRI [AUROC 0.82 (95%CI 0.74-0.90)] and Fib-4 [AUROC 0.86 (95%CI 0.80-0.93)]. In general, the optimal platelet cut-off had a higher negative predictive value than positive predictive values (Table 4).

| Platelet cut-off (× 109/L) | AUROC | Sensitivity (%) | Specificity (%) | Positive predictive value (%) | Negative predictive value (%) | |

| Entire validation cohort | 143 | 0.85 (0.76-0.93) | 79 | 84 | 33 | 98 |

| HBV | 143 | 0.81 (0.53-1.00) | 83 | 82 | 29 | 98 |

| HCV | 143 | 0.83 (0.72-0.94) | 75 | 86 | 31 | 98 |

| HDV | 143 | 0.87 (0.74-1.00) | 100 | 60 | 47 | 100 |

For simplicity, it may be suggested that a platelet cut-off of 143 × 109/L be rounded to 140 × 109/L instead. The sensitivity, specificity, positive predicative value, and negative predictive values were not greatly altered in the validation cohort (73%, 86%, 48%, 95% respectively) (Table 5).

| Platelet counts (× 109/L) | Sensitivity (%) | Specificity (%) | Positive predictive value (%) | Negative predictive value (%) |

| 130 | 67 | 91 | 57 | 94 |

| 140 | 73 | 86 | 48 | 95 |

| 143 | 74 | 83 | 44 | 94 |

| 150 | 78 | 78 | 38 | 95 |

In the largest reported cross-sectional retrospective study of patients with chronic viral hepatitis evaluating routinely measured laboratory tests, platelet counts were identified as a surrogate marker for the development of cirrhosis. In comparison to other commonly performed clinical tests in a primary care setting, platelet counts performed the best and had the highest AUROC in identifying patients with cirrhosis. An optimized platelet cut-off value of 143 × 109/L across all chronic viral hepatitis infections suggesting cirrhosis was validated. A rounded platelet count of 140 × 109/L appears to show similar performance in identifying cirrhosis as well. Given that primary care providers are uniquely positioned in managing patients with chronic viral hepatitis, these results offer a simple and effective method to determine severity of liver disease in a primary care setting without additional testing. The ability to rule out cirrhosis through a simple surrogate marker may provide a simplified approach to connecting patients to treatment and optimal medical management.

Thrombocytopenia is often recognized as a complication of liver disease and has been used as a surrogate marker for varices, portal hypertension, and increased risk of hepatocellular carcinoma; typical complications of cirrhosis[21-23]. Mechanistically, there are several possible explanations for the thrombocytopenia in chronic liver disease; such as, splenic sequestration of platelets, decreased platelet production, and decreased thrombopoietin activity[22,24]. Historically, only thrombocytopenia below 50 × 109/L has demonstrated clinical relevance[25]. Recently, various scores incorpo

Additionally, platelets have been incorporated into non-invasive biomarkers of fibrosis such as Fib-4 and APRI, formulas typically utilized by sub-specia

According to the World Health Organization, health equity has still not been achieved by countries of all socioeconomic levels. In order to breach this gap in care, an increasing number of primary care physicians are being trained to care for patients with chronic liver disease through programs and resources such as Project ECHO, HepCCaTT (offering care for HCV), and the HBV Primary Care Workgroup[5,33-35] (all in the United States) or the Mukh-Mantri Punjab Hepatitis C Relief Fund in India[7]. However, chronic liver disease is just one of many chronic illnesses that primary care physicians are called upon to manage in these settings. The utility of other non-invasive markers may be limited in resource poor-settings. Both Fib-4 and APRI require multiple laboratory marker measurements, calculations, and knowledge of validated cut-offs for correct interpretation[9,13,32]. VCTE, while simple and useful technology, is expensive and may not be available at all centers of care. In addition, complex algorithms including a sequential use of non-invasive markers to improve their accuracy have also been suggested[36,37]. These non-invasive markers are useful in specialist care settings, but might not be optimal in resource limited settings where primary-care physicians are the main point of care.

While platelet count has been proven to be an important indicator of liver disease progression, it is important to note that the platelet counts represented in this retrospective single center study’s cohort may differ from those seen in a typical primary care setting. Given the specialized setting of the National Institutes of Health, this population may have a higher prevalence of cirrhosis than the typical primary care setting, and this may enhance the performance of platelet count as a marker of cirrhosis within this study. This study proposes the use of a single, commonly measured laboratory marker to monitor the progression of chronic viral hepatitis and identifies a clinically relevant cut-off for clinical decision making and to rule-out cirrhosis. Further studies would provide more information about the clinical outcomes of these patients, on what the degree of thrombocytopenia may imply for these patients and how platelet counts should be included in non-invasive monitoring algorithms. The strength of this study lies in the large cohort of chronically infected patients with histology and three etiologies of viral hepatitis with the inclusion of patients with chronic delta hepatitis.

While platelet count has been established as a surrogate marker for disease pro

The diagnosis of cirrhosis in patients with chronic viral hepatitis has both treatment and management implications. Identifying these patients is crucial in order to ensure proper care, prevent complications of cirrhosis and for judicious allocation of resources.

With an increasing reliance on primary care in management of chronic viral hepatitis, reliable simple non-invasive assessments of cirrhosis are needed in order to identify cirrhosis and to determine requirement of referral to specialized care.

To evaluate the performance of single laboratory markers, with an emphasis on platelet counts, to identify development of cirrhosis in patients with chronic hepatitis B virus, hepatitis C virus, and hepatitis D virus infection.

Retrospective study comparing the accuracy of single laboratory markers in deter

In a cohort of 1027 subjects, compared to other single laboratory markers, platelet counts performed the best at identifying cirrhosis [AUROC 0.86 (0.82-0.90)] and sensitivity 77%, specificity 83%, positive predictive value 44%, and negative predictive value 95%. The optimal cut-off point was 143 × 109/L. This performed equally well in a validation cohort.

Platelet counts are the most reliable single serological marker in ruling out cirrhosis in patients with chronic viral hepatitis. Thrombocytopenia can potentially be used in the primary care setting for management of patients with viral hepatitis.

Future research directions include validation of this cut-off value of platelet counts in other cohorts of patients with liver disease and evaluation of longitudinal trends of thrombocytopenia.

Manuscript source: Invited manuscript

Corresponding Author's Membership in Professional Societies: American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases.

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country/Territory of origin: United States

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C, C, C, C, C

Grade D (Fair): D, D

Grade E (Poor): E

P-Reviewer: Ferraioli G, Garbuzenko DV, Kreisel W, Liu N, Maslennikov R, Pluta M, Qi XS S-Editor: Gao CC L-Editor: A P-Editor: Yuan YY

| 1. | World Health Organization. Global Hepatitis Report, 2017. [cited 21 January 2021]. In: World Health Organization [Internet]. Available from: https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/255016/9789241565455-eng.pdf;jsessionid=8B2E8C7D9287FF00B5C9E04740D157C9?sequence=1. |

| 2. | Schillie S, Wester C, Osborne M, Wesolowski L, Ryerson AB. CDC Recommendations for Hepatitis C Screening Among Adults - United States, 2020. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2020;69:1-17. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 261] [Cited by in RCA: 353] [Article Influence: 70.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Weinbaum CM, Williams I, Mast EE, Wang SA, Finelli L, Wasley A, Neitzel SM, Ward JW; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Recommendations for identification and public health management of persons with chronic hepatitis B virus infection. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2008;57:1-20. [PubMed] |

| 4. | Wallace J, Hajarizadeh B, Richmond J, McNally S, Pitts M. Managing chronic hepatitis B - the role of the GP. Aust Fam Physician. 2012;41:893-898. [PubMed] |

| 5. | Lewiecki EM, Rochelle R. Project ECHO: Telehealth to Expand Capacity to Deliver Best Practice Medical Care. Rheum Dis Clin North Am. 2019;45:303-314. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. National Viral Hepatitis Action Plan 2017-2020. [cited 21 January 2021]. In: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services [Internet]. Available from: https://www.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/National%20Viral%20Hepatitis%20Action%20Plan%202017-2020.pdf. |

| 7. | Dhiman RK, Grover GS, Premkumar M, Taneja S, Duseja A, Arora S, Rathi S, Satsangi S, Roy A; MMPHCRF Investigators. Decentralized care with generic direct-acting antivirals in the management of chronic hepatitis C in a public health care setting. J Hepatol. 2019;71:1076-1085. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 46] [Article Influence: 7.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | AASLD-IDSA HCV Guidance Panel. Hepatitis C Guidance 2018 Update: AASLD-IDSA Recommendations for Testing, Managing, and Treating Hepatitis C Virus Infection. Clin Infect Dis. 2018;67:1477-1492. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 477] [Cited by in RCA: 477] [Article Influence: 68.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Wai CT, Greenson JK, Fontana RJ, Kalbfleisch JD, Marrero JA, Conjeevaram HS, Lok AS. A simple noninvasive index can predict both significant fibrosis and cirrhosis in patients with chronic hepatitis C. Hepatology. 2003;38:518-526. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2762] [Cited by in RCA: 3242] [Article Influence: 147.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Renou C, Muller P, Jouve E, Bertrand JJ, Raoult A, Benderriter T, Halfon P. Revelance of moderate isolated thrombopenia as a strong predictive marker of cirrhosis in patients with chronic hepatitis C virus. Am J Gastroenterol. 2001;96:1657-1659. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Cheung RC, Currie S, Shen H, Bini EJ, Ho SB, Anand BS, Hu KQ, Wright TL, Morgan TR; VA HCV-001 Study Group. Can we predict the degree of fibrosis in chronic hepatitis C patients using routine blood tests in our daily practice? J Clin Gastroenterol. 2008;42:827-834. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Garcia-Tsao G, Abraldes JG, Berzigotti A, Bosch J. Portal hypertensive bleeding in cirrhosis: Risk stratification, diagnosis, and management: 2016 practice guidance by the American Association for the study of liver diseases. Hepatology. 2017;65:310-335. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1108] [Cited by in RCA: 1438] [Article Influence: 179.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (3)] |

| 13. | Sterling RK, Lissen E, Clumeck N, Sola R, Correa MC, Montaner J, S Sulkowski M, Torriani FJ, Dieterich DT, Thomas DL, Messinger D, Nelson M; APRICOT Clinical Investigators. Development of a simple noninvasive index to predict significant fibrosis in patients with HIV/HCV coinfection. Hepatology. 2006;43:1317-1325. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2633] [Cited by in RCA: 3555] [Article Influence: 187.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Lilford RJ, Bentham LM, Armstrong MJ, Neuberger J, Girling AJ. What is the best strategy for investigating abnormal liver function tests in primary care? BMJ Open. 2013;3. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Kim WR, Berg T, Asselah T, Flisiak R, Fung S, Gordon SC, Janssen HL, Lampertico P, Lau D, Bornstein JD, Schall RE, Dinh P, Yee LJ, Martins EB, Lim SG, Loomba R, Petersen J, Buti M, Marcellin P. Evaluation of APRI and FIB-4 scoring systems for non-invasive assessment of hepatic fibrosis in chronic hepatitis B patients. J Hepatol. 2016;64:773-780. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 170] [Cited by in RCA: 224] [Article Influence: 24.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Degos F, Perez P, Roche B, Mahmoudi A, Asselineau J, Voitot H, Bedossa P; FIBROSTIC study group. Diagnostic accuracy of FibroScan and comparison to liver fibrosis biomarkers in chronic viral hepatitis: a multicenter prospective study (the FIBROSTIC study). J Hepatol. 2010;53:1013-1021. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 318] [Cited by in RCA: 336] [Article Influence: 22.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Castera L. Noninvasive methods to assess liver disease in patients with hepatitis B or C. Gastroenterology. 2012;142:1293-1302.e4. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 438] [Cited by in RCA: 452] [Article Influence: 34.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Ishak K, Baptista A, Bianchi L, Callea F, De Groote J, Gudat F, Denk H, Desmet V, Korb G, MacSween RN. Histological grading and staging of chronic hepatitis. J Hepatol. 1995;22:696-699. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3521] [Cited by in RCA: 3782] [Article Influence: 126.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 19. | Knodell RG, Ishak KG, Black WC, Chen TS, Craig R, Kaplowitz N, Kiernan TW, Wollman J. Formulation and application of a numerical scoring system for assessing histological activity in asymptomatic chronic active hepatitis. Hepatology. 1981;1:431-435. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2558] [Cited by in RCA: 2507] [Article Influence: 57.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Hinkle DE WW, Jurs SG. Applied Statistics for the Behavioral Sciences. 5th ed. Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 2003. |

| 21. | de Franchis R; Baveno VI Faculty. Expanding consensus in portal hypertension: Report of the Baveno VI Consensus Workshop: Stratifying risk and individualizing care for portal hypertension. J Hepatol. 2015;63:743-752. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2011] [Cited by in RCA: 2290] [Article Influence: 229.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (3)] |

| 22. | Afdhal N, McHutchison J, Brown R, Jacobson I, Manns M, Poordad F, Weksler B, Esteban R. Thrombocytopenia associated with chronic liver disease. J Hepatol. 2008;48:1000-1007. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 380] [Cited by in RCA: 403] [Article Influence: 23.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Lu SN, Wang JH, Liu SL, Hung CH, Chen CH, Tung HD, Chen TM, Huang WS, Lee CM, Chen CC, Changchien CS. Thrombocytopenia as a surrogate for cirrhosis and a marker for the identification of patients at high-risk for hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancer. 2006;107:2212-2222. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 106] [Cited by in RCA: 121] [Article Influence: 6.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Tana MM, Zhao X, Bradshaw A, Moon MS, Page S, Turner T, Rivera E, Kleiner DE, Heller T. Factors associated with the platelet count in patients with chronic hepatitis C. Thromb Res. 2015;135:823-828. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Giannini EG. Review article: thrombocytopenia in chronic liver disease and pharmacologic treatment options. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2006;23:1055-1065. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 134] [Cited by in RCA: 136] [Article Influence: 7.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Augustin S, Pons M, Maurice JB, Bureau C, Stefanescu H, Ney M, Blasco H, Procopet B, Tsochatzis E, Westbrook RH, Bosch J, Berzigotti A, Abraldes JG, Genescà J. Expanding the Baveno VI criteria for the screening of varices in patients with compensated advanced chronic liver disease. Hepatology. 2017;66:1980-1988. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 224] [Cited by in RCA: 204] [Article Influence: 25.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Kew GS, Chen ZJ, Yip AW, Huang YWC, Tan LY, Dan YY, Gowans M, Huang DQ, Lee GH, Lee YM, Lim SG, Low HC, Muthiah MD, Tai BC, Tan PS. Identifying Patients With Cirrhosis Who Might Avoid Screening Endoscopy Based on Serum Albumin and Bilirubin and Platelet Counts. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021;19:199-201.e2. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Lilford RJ, Bentham L, Girling A, Litchfield I, Lancashire R, Armstrong D, Jones R, Marteau T, Neuberger J, Gill P, Cramb R, Olliff S, Arnold D, Khan K, Armstrong MJ, Houlihan DD, Newsome PN, Chilton PJ, Moons K, Altman D. Birmingham and Lambeth Liver Evaluation Testing Strategies (BALLETS): a prospective cohort study. Health Technol Assess. 2013;17:i-xiv, 1-307. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 50] [Cited by in RCA: 47] [Article Influence: 3.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Xu Q, Higgins T, Cembrowski GS. Limiting the testing of AST: a diagnostically nonspecific enzyme. Am J Clin Pathol. 2015;144:423-426. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Newsome PN, Cramb R, Davison SM, Dillon JF, Foulerton M, Godfrey EM, Hall R, Harrower U, Hudson M, Langford A, Mackie A, Mitchell-Thain R, Sennett K, Sheron NC, Verne J, Walmsley M, Yeoman A. Guidelines on the management of abnormal liver blood tests. Gut. 2018;67:6-19. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 236] [Cited by in RCA: 335] [Article Influence: 47.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 31. | Chou R, Wasson N. Blood tests to diagnose fibrosis or cirrhosis in patients with chronic hepatitis C virus infection: a systematic review. Ann Intern Med. 2013;158:807-820. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 268] [Cited by in RCA: 271] [Article Influence: 22.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Patel K, Sebastiani G. Limitations of non-invasive tests for assessment of liver fibrosis. JHEP Rep. 2020;2:100067. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 68] [Cited by in RCA: 180] [Article Influence: 36.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Marciano S, Haddad L, Plazzotta F, Mauro E, Terraza S, Arora S, Thornton K, Ríos B, García Dans C, Ratusnu N, Calanni L, Allevato J, Sirotinsky ME, Pedrosa M, Gadano A. Implementation of the ECHO® telementoring model for the treatment of patients with hepatitis C. J Med Virol. 2017;89:660-664. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Boodram B, Kaufmann M, Aronsohn A, Hamlish T, Peregrine Antalis E, Kim K, Wolf J, Rodriguez I, Millman AJ, Johnson D. Case Management and Capacity Building to Enhance Hepatitis C Treatment Uptake at Community Health Centers in a Large Urban Setting. Fam Community Health. 2020;43:150-160. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Hepatitis B Primary Care Workgroup. Hepatitis B Management: Guidance for the Primary Care Provider. [cited 21 January 2021]. In: Hepatitis B Online [Internet]. Available from: https://www.hepatitisb.uw.edu/page/primary-care-workgroup/guidance. |

| 36. | Boursier J, de Ledinghen V, Zarski JP, Fouchard-Hubert I, Gallois Y, Oberti F, Calès P; multicentric groups from SNIFF 32; VINDIAG 7, and ANRS/HC/EP23 FIBROSTAR studies. Comparison of eight diagnostic algorithms for liver fibrosis in hepatitis C: new algorithms are more precise and entirely noninvasive. Hepatology. 2012;55:58-67. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 88] [Cited by in RCA: 94] [Article Influence: 7.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Sebastiani G, Halfon P, Castera L, Pol S, Thomas DL, Mangia A, Di Marco V, Pirisi M, Voiculescu M, Guido M, Bourliere M, Noventa F, Alberti A. SAFE biopsy: a validated method for large-scale staging of liver fibrosis in chronic hepatitis C. Hepatology. 2009;49:1821-1827. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 129] [Cited by in RCA: 126] [Article Influence: 7.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |