CASE REPORT

A previously healthy 20-year-old woman experienced nausea, non-bloody vomiting and diarrhea for several weeks, accompanied by abdominal pain and distention, leg edema and weight gain of 20 lbs. She had had an uneventful pregnancy and delivery ten weeks earlier. There was no history of transfusions, recent travel, respiratory symptoms, rash, allergies, or ill contact. She had no history of liver or heart disease. She was not consuming alcohol or any illicit drug, and was taking neither medications nor supplements. She had no family history of liver disease, asthma or coagulation disorder.

On physical examination, the patient was alert and showed no distress, was afebrile and hemodynamically stable. The skin and mucosa were anicteric and clear without spider angiomata, and the cardiovascular and thyroid examinations were normal. Chest auscultation demonstrated decreased breath sounds over the left lower lobe, no wheezing or crackles; dullness to percussion over the left lower lobe with increased egophony was detected. The abdomen was distended and tender diffusely with shifting dullness present; no caput medusae, rebound or guarding were observed. Bilateral leg edema was present. No lymphadenopathy or hepatosplenomegaly were found.

Laboratory data were as follows: Hgb 11 g/dL, Htc 34, PLT 278 k/mL, WBC 12.8 k/mL, differential: segmentonuclear neutrophils 50%, lymphocytes 9%, monocytes 1%, eosinophils 38%. Serum electrolytes, coagulation studies, thyroid and liver tests were normal. HIV (human immunodeficiency virus) ELISA (enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay ) was negative. Parasitic infestation was excluded by negative stool studies and serology for strongyloides and toxocara.

On abdominal ultrasonography, the liver was found to be of normal size and echogenicity, and all vessels were patent. There was a large amount of pelvic and abdominal ascites and a left-sided pleural effusion.

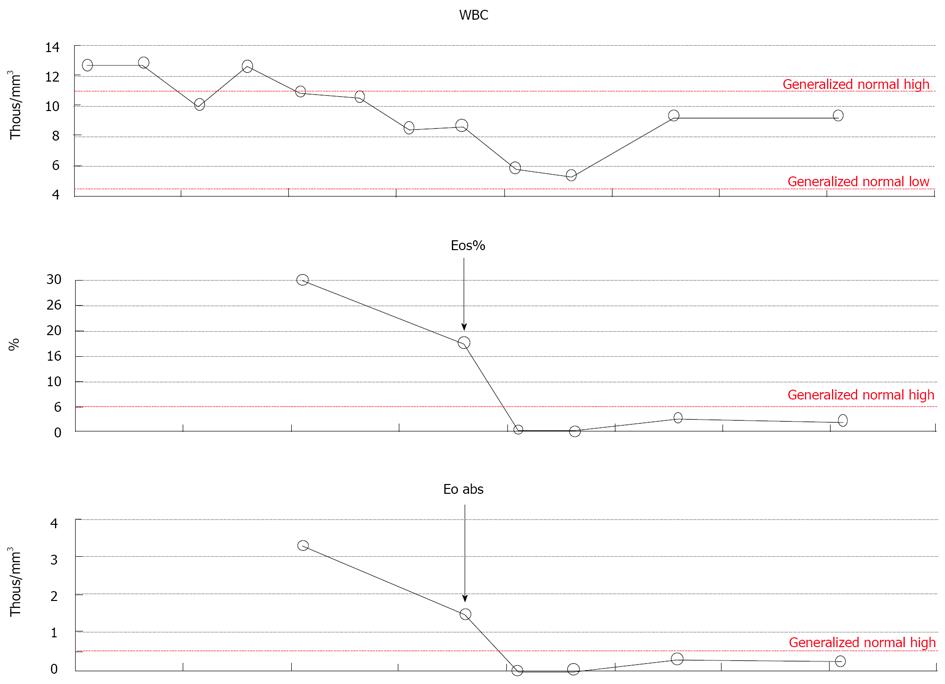

Diagnostic paracentesis revealed hazy dark fluid with no cytological signs of malignancy, with protein level 4.5 g/dL, albumin 2.4 g/dL, RBC 12 k/mL, WBC 1.780/mL with significant eosinophilia of 82%. Ascitic fluid for bacterial culture and for tuberculosis had no growth. Bone marrow biopsy showed normal hematopoesis with 20%-25% eosinophils and normal cytogenetics. Esophagogastroduodenoscopy demonstrated mild gastric mucosal erythema, and several gastric polyps 3-5 mm in size. Mucosal biopsies were obtained, and were consistent with mild reflux esophagitis, reactive glandular changes and regenerative polyps of the stomach, and normal villous architecture of the duodenum. No eosinophils in the mucosal biopsies were found. Unfortunately, the patient refused colonoscopy or laparoscopy which would have been the next steps in the clinical work-up of eosinophilic gastroenteritis. She was empirically treated with prednisone 40 mg qd po, with rapid resolution of her symptoms and eosinophilia (Figure 1).

Figure 1 Decrease in eosinophilia observed in response to steroids.

The arrow indicates time of the initiation of prednisone therapy. The dots represent concentration of the eosinophils on a given day.

DISCUSSION

Eosinophilic ascites (EA) is probably the most unusual and rare presentation of eosinophilic gastroenteritis (EGE). EGE is characterized as eosinophil-rich inflammation of the gastrointestinal tract in the absence of known causes for eosinophilia, for example malignancy, allergy, parasitic infestation, Chug-Strause syndrome or HTLV infection. It was first described by Kaijser in 1937[3] and since then multiple cases have been reported. EGE is an uncommon condition, and data regarding its prevalence and the demographic distribution of the disease is scarce. However, in the last decade, a progressive increase in incidence has been noticed in both the pediatric and the adult population. This condition may affect individuals of any age group, and although rare, there are reports of cases of EGE and EA in both extremes of age, i.e. in infants and in the elderly population[4]. A World Wide Web database for eosinophilic gastrointestinal disorders has been established, and by its report EGE is associated with atopic conditions in 80% of cases, and with food allergy in 62% of cases. In addition, 16% of patients have, or have had, a family member with a similar disorder[5]. It also seems to be found predominantly in males. Interestingly, EA is more common in the female population[6]. Mortality from EGE is very low and usually due to intestinal perforation, but morbidity may be significant: malnutrition and failure to thrive, abdominal pain, gastric dysmotility, dysphagia, nausea, vomiting, intussusception and obstruction may develop.

Eosinophilic infiltration of the digestive tract mucosa is not unique to EGE. It has been reported in Ig-E mediated food allergies, GERD, and inflammatory bowel disease (IBD)[7-10].

Pathogenesis

The etiology and pathogenesis of EGE is not entirely clear. It seems to come about as a result of a complex interplay of environment, genetics and the immune system; an association between EGE, collagenoses, allergy and hypereosinophilic syndrome (HES) has been reported[7,11,12].

Eosinophilic gastrointestinal disorders have a tendency to affect multiple members of the same family, and are associated with food allergies and atopy in many cases[5,7]. Both cellular and humoral immunity seems to be involved, placing EGE between purely IgE-mediated disorders, such as food anaphylaxis, and non-IgE-mediated disorders, like IBD and celiac disease[8,13]. The role of Ig-E mediated mast cell degranulation in the pathogenesis of EGE is indirectly confirmed by the effectiveness of anti-Ig-E treatment in patients with EGE[13].

Eosinophils are normally present in various tissues at low levels; in the gastrointestinal tract, they are predominantly located in the lamina propria of the mucosa, but not in the Peyer’s patches. However, these areas become infiltrated with eosinophils in EGE[8,14]. The role of the eosinophils in the gastrointestinal tract is primarily limited to their role in innate anti-parasite immunity, which brings about a regulatory influence on the function of other lymphocytes, participation in antigen presentation, and, possibly, tumor surveillance[15-18]. The exact reasons why eosinophils accumulate in the gastrointestinal mucosa are not clear, but their degranulation leads to a severe inflammatory response in the mucosa via reactive oxygen species formation, eosinophil derived neurotoxins, and halide acids[8]. Substances found in eosinophilic granules, major basic protein (MBP) I and II as well as eosinophil cationic protein (ECP) accumulate in the extracellular spaces of intestinal tissue of the patients with EGE, as demonstrated by biopsies[8,19]. Furthermore, the disease activity in these patients correlates with the eosinophil concentration in the tissue[19].

Eosinophilic gastroenteritis is classified according to the predominance of eosinophilic infiltration in the different layers of the intestinal wall (Klein classification): mucosal, muscularis and serosal forms[19]. Clinical manifestations depend on the affected layers and range from barely perceptible symptoms to intestinal obstruction or ascites. The most common mucosal form of EGE manifests with abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, sometimes with hematochezia, and protein-losing enteropathy, which may lead to weight loss and malnutrition. Muscularis involvement results in gut wall thickening and may lead to obstruction. The serosal form is the most unusual, and leads to EA, as suspected in the case of the patient described in this article. EA is often accompanied by pleural effusion (also seen in the patient described) and less frequently by ileus formation. It may take a relapsing-remitting course in one fourth of patients[6,20,21]. In ECG's serosal form, mucosal biopsies may contain no eosinophils, since the serosal layer is predominantly involved.

As a part of HES, EGE may occur in a multitude of clinical scenarios which require a high degree of suspicion in order to make a correct diagnosis. In many patients it may be accompanied by hepatosplenomegaly or isolated splenomegaly[12,22]. Rare cases of EA accompanied by development of pancreatitis, cholangitis, and hepatic dysfunction due to eosinophilic liver infiltration and necrosis are described in the literature[23-26]. Multiorgan involvement in HES has been described as well. Vandewiele et al described a patient with EGE with massive EA, pulmonary disease, nervous system involvement and seizures[27].

There are a very few reports of EGE affecting young women in the post-partum period. Of these, some patients developed gastrointestinal symptoms as a part of HES, also presenting with damage to other end-organs such as heart, lungs, and skin[28]. Others had isolated EGE and some had EA. Recurrence of the symptoms with subsequent pregnancies has been described.

Diagnosis

There is no single diagnostic test or procedure that would point directly to the diagnosis of EGE, and there are no strict or uniform diagnostic criteria for it. When it is suspected on the basis of clinical presentation or the results of tissue biopsy, other causes of hypereosinophilia, such as drug reaction, malignancy, parasites, infection or systemic disease should first be excluded. Diagnostic evaluation of the patient with suspected EGE should include complete blood cell count and differential, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, C reactive protein, amylase, stool studies for ova and parasites, upper and lower gastrointestinal endoscopy with biopsies, bone marrow biopsy, allergen studies (skin testing and RASTs), and IgE and IL-5 levels. In the presence of ascites, paracentesis should be performed, and the ascitic fluid should be sent for cytology, cell count and differential, gram stain, culture, including culture for tuberculosis, glucose, protein, albumin, lactate dehydrogenase, IL-5, and IgE levels. Isolated elevation of IL-5 in ascitic fluid, but not in the serum in a patient with EA has been reported as well[29].

Parasitic infestation with Strongiloides and Toxocara may present with symptoms of gastroenteritis and EA, and they need to be excluded prior to making the diagnosis of EGE[30,31]. Of note, detection of a parasitic infestation especially with Strongiloides is important, since initiation of steroid therapy in patients with this condition may lead to disseminated infection and death. Serum Ig-E elevation may point to occult parasitic infestation or an atopic variant of EGE[8]. Skin allergen testing may help pinpoint the offending substance, avoidance of which may lead to the resolution of symptoms.

Endoscopic evaluation may demonstrate changes in the gastrointestinal mucosa varying from near-normal appearance to severe inflammation, with erosions, exudates, furrowing, polyps, mucosal rings, and stricture formation[32]. Biopsies demonstrate eosinophil-rich inflammation, sometimes with extracellular eosinophilic granules, containing both MBP and ECP, which can be detected immunohistochemically[8,33]. The number of eosinophils and their degranulation might be underestimated when evaluated by conventional staining with hematoxyllin-eosin Immunohistochemical tissue processing has been found to provide more precise results[34,35]. On the other hand, eosinophils may be absent in the biopsy samples from the patients with patchy disease[19].

The diagnosis of EA might be difficult to make, since it is more common in the serosal form of EGE in which systemic eosinophilia might be absent and there may be no eosinophilic infiltration of the gastrointestinal mucosa. Although laparoscopic serosal biopsies may be required for a definitive diagnosis, ascitic fluid eosinophilia and a dramatic response to treatment with steroids indirectly confirm the diagnosis of EGE and EA[21], as was observed in this patient. There are also reports of ultrasound-guided percutaneous biopsy of the stomach and jejunum for confirmation of serosal and muscularis forms of EGE[36].

Abdominal ultrasound and computer tomography may demonstrate intestinal wall thickening, ascites, pleural effusions, and hepatosplenomegaly in patients with EGE[37].

Treatment

A large proportion of patients diagnosed with EGE report a history of allergy, and occasionally, elimination of the offending substance leads to resolution of symptoms. Some patients experience spontaneous resolution of symptoms, others have a relapsing-remitting course and require long-term treatment with steroids, usually at a low dose[38,39]. Multiple therapeutic strategies have been tried in order to avoid steroid side effects. Enteric coated budesonide and sodium cromoglycate (SCG), a mast cell membrane stabilizer, have been used successfully for treatment of some atopic cases of EGE[40,41].

Novel approaches in the treatment of patients with EGE include the use of leukotriene receptor antagonists and monoclonal antibodies against Ig-E and IL-5. Montelucast, a leukotriene receptor inhibitor, has been successfully used in treatment of serosal EGE[42]. Omalizumab and mepolizumab, anti-Ig-E and anti-IL-5 monoclonal antibodies respectively, have shown promising results in the treatment of patients with EGE in clinical trials[13,43]. These medications offer a steroid-sparing approach to treatment of EGE which aids in avoiding the serious side effects of steroid therapy. The latter is especially important in the pediatric patient population.

In summary, EA is a rare presentation of EGE and should be considered when facing a patient with ascites in the absence of liver disease, and with refractory gastrointestinal symptoms, especially in the presence of a concomitant allergic condition. In many cases of EGE, especially the serosal form in which systemic eosinophilia and eosinophilic infiltration of gastrointestinal mucosa might be absent, diagnosis may be hard to make and may require an extensive and invasive work up and surgery[44]. When EGE presents as a part of HES, patients should be referred for appropriate hematological evaluation, since eventual malignant transformation is a possibility[45]. Occurrence of this syndrome postpartum has been described in a few case reports. Steroid therapy is effective. However, long term steroid therapy is sometimes required to prevent reoccurrence of the EGE and EA, and steroid-sparing treatment options should be considered. Diagnosis of this unusual disorder requires a high index of suspicion accompanied by the judicious application of tests.