Published online Aug 15, 2010. doi: 10.4291/wjgp.v1.i3.106

Revised: June 3, 2010

Accepted: June 10, 2010

Published online: August 15, 2010

A 76 year old woman with bloody stools and symptomatic anemia presented to the Emergency Department approximately 2 wk after computed tomography (CT)-guided cryoablation to a 4.5 cm renal cell carcinoma on her left posterior kidney. The patient was initially prepped for a colonoscopy to view possible causes of lower gastrointestinal bleeding. However, the patient had a CT with PO contrast that revealed a variation of a renoalimentary fistula. The patient was subsequently brought to the operating room, and it was discovered that a colo-renal fistula had formed, with transmural perforation of the posterior descending colon. A left nephrectomy, left colectomy with colostomy and Hartmann’s pouch was performed.

- Citation: Wysocki JD, Joshi V, Eiser JW, Gil N. Colo-renal fistula: An unusual cause of hematochezia. World J Gastrointest Pathophysiol 2010; 1(3): 106-108

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2150-5330/full/v1/i3/106.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4291/wjgp.v1.i3.106

Lower gastrointestinal bleeding in an elderly patient has a variety of etiologies. The most common causes of bleeding typically include diverticulosis, ischemic colitis, cancer, and angiodysplasia. Invasive procedures, such as percutaneous ablation, have introduced a new mechanism for the discovery of renalimentary fistula (RFA), of which only a few cases have been described in the literature. In 2006, Arruda et al described a case of renoduodenal fistula after RFA. In 2007, Vanderbrink et al described the first known case of colo-renal fistula after percutaneous cryoablation of renal cell carcinoma. The patient in their case was treated successfully with an internal ureteral stent and the fistula resolved. We present a patient with a colo-renal fistula who required an open surgical procedure as a result of the severity of her clinical presentation. A literature review of colo-renal fistulae is also presented.

A 76 year-old African American woman presented with a one day history of hematochezia and syncope. She also noted lower abdominal pain, but denied nausea or vomiting. Prior to these recent bowel movements, she had been constipated for the past 10 d. She had had a negative colonoscopy 20 years ago. She has type 2 diabetes, hypertension, and renal cell carcinoma. Two wk ago, she had computed tomography (CT)-guided percutaneous palliative cryoablation to a 4.5 cm tumor on her left kidney. Since the surgery, she had had a poor appetite and had been eating less.

She was afebrile, with a blood pressure of 142/65 mmHg; her other vital signs were stable. Her left lower abdomen was tender to deep palpation. She had hyperactive bowel sounds and, on rectal examination, bright red blood was noted.

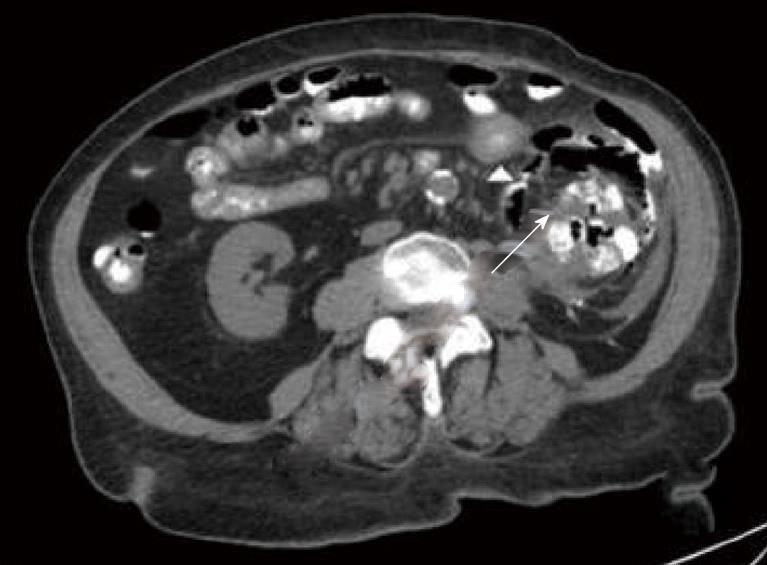

Upon admission, her hemoglobin was 9.1 g/dL. Six h later, it had dropped to 7.3 g/dL. Her white blood cell count was 10 300/μL, platelet count 481 000/mL, creatinine 1.7 mg/dL, prothrombin time/International Normalized Ratio - 10.0 s/0.9. Her urinalysis had glucose > 1000 mg/dL, 26 white blood cells/high power field and trace mucous. There was no fecaluria. A CT scan revealed a 6.8 cm × 7.2 cm × 7.5 cm area within the left kidney, representing prior cryoablation of renal cell carcinoma. Inflammatory changes, oral contrast, and foci of air (Figure 1) were also noted. Small and large bowel were both in close association with this area and possibly denoted a bowel fistula. Extensive atherosclerosis of the abdominal aorta was also noted. The patient was taken to surgery and a left nephrectomy, left colectomy and Hartman’s Pouch was completed.

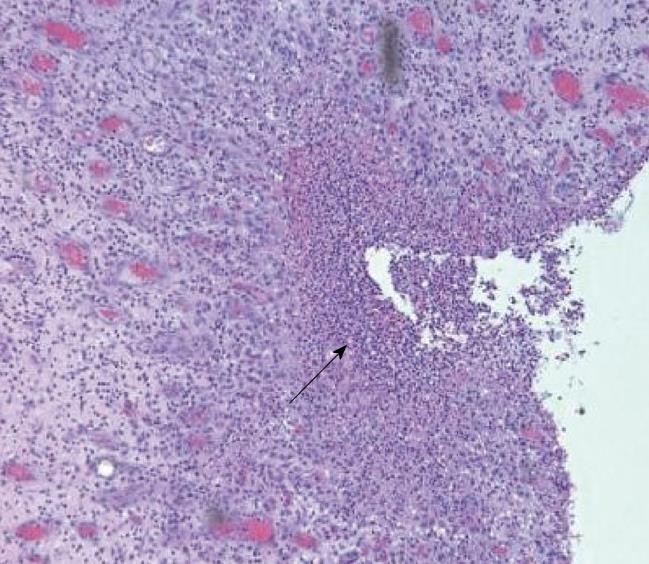

The left kidney and left colon were surgically resected and reviewed histopathologically (Figures 2 and 3). The kidney had a completely infarcted 6 cm left lower pole tumor, with nephro-colonic fistula of the left colon. The colon demonstrated focal acute colitis with perforation and fistulous tract to the kidney.

Hematochezia in an elderly patient has a variety of etiologies, including diverticulosis, ischemic colitis, cancer, and angiodysplasia. Recently, percutaneous cryoablation has introduced a new mechanism for the discovery of lower gastrointestinal (GI) bleeding. While the colon is typically hydrodissected during cryoablation to reduce the risk of injury to the descending colon, it is possible to inadvertently puncture the bowel with an applicator or extension of the ablation zone. Perforation may be followed by fistula and abscess formation[1]. Fistulography is valuable in diagnosing some types of fistulae, but Parvey et al[2] found that CT was the single most useful diagnostic modality for colo-renal fistula. While colonoscopy is usually indicated in lower GI bleeding, there is no body of evidence to support this procedure for the management of colo-renal fistulae.

Conservative management should be considered in stable patients with normal kidney function and previous success with ureteral stenting to close fistulas[3]. When conservative management is not an option, or the fistula is complex, surgery is the primary method of treatment. Symptoms indicating that surgery is required include intestinal obstruction, bleeding, sepsis, or renal failure[4] and the surgery then should be nephrectomy and partial bowel resection. Due to this patient’s co-morbidities, surgical exploration was performed to treat her lower GI bleeding.

Only a few case reports describe colo-renal fistula after ablative techniques: Uribe et al[5] and Weizer et al[6] described them after laparoscopic and percutaneous RFA, respectively. Silverman[7] and Vanderbrink[3] described colo-renal fistulae after percutaneous cryoablation of renal cell carcinoma. Although rare, physicians should be aware of the risks of these ablative techniques. Patients may appear to have a classic presentation of hematochezia, but, in reality, require timely imaging, and close coordination with the surgical team. In this case, a carefully taken history of recent intra-abdominal interventions prevented unnecessary endoscopic evaluation.

Peer reviewers: Qing Zhu, MD, PhD, NIH/NIAID, Bethesda, MD 20814, United States; Elke Cario, MD, Professor, University Hospital of Essen, Division of Gastroenterology and Hepatology, Institutsgruppe I, Virchowstr. 171, Essen 45147, Germany

| 1. | Uppot RN, Silverman SG, Zagoria RJ, Tuncali K, Childs DD, Gervais DA. Imaging-guided percutaneous ablation of renal cell carcinoma: a primer of how we do it. AJR. 2009;192:1558-1570. |

| 2. | Parvey HR, Cochran ST, Payan J, Goldman S, Sandler CM. Renocolic fistulas: complementary roles of computed tomography and direct pyelography. Abdom Imaging. 1997;22:96-99. |

| 3. | Vanderbrink BA, Rastinehad A, Caplin D, Ost MC, Lobko I, Lee BR. Successful conservative management of colorenal fistula after percutaneous cryoablation of renal-cell carcinoma. J Endourol. 2007;21:726-729. |

| 4. | Feldman M, Friedman S, Brandt LJ. Sleisenger & Fordtran’s Gastrointestinal and Liver Disease, 8th edition. Philadelphia. 2006;534-538. |

| 5. | Uribe PS, Costabile RA, Peterson AC. Progression of renal tumors after laparoscopic radiofrequency ablation. Urology. 2006;68:968-671. |