Published online Apr 28, 2017. doi: 10.4329/wjr.v9.i4.178

Peer-review started: October 17, 2016

First decision: January 16, 2017

Revised: February 16, 2017

Accepted: February 28, 2017

Article in press: March 2, 2017

Published online: April 28, 2017

Processing time: 196 Days and 19.9 Hours

Congenital malformations of spine and spinal cord are collectively termed as spinal dysraphism. It includes a heterogeneous group of anomalies which result from faulty closure of midline structures during development. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is now considered the imaging modality of choice for diagnosing these conditions. The purpose of this article is to review the normal development of spinal cord and spine and reviewing the MRI features of spinal dysraphism. Although imaging of spinal dysraphism is complicated, a systematic approach and correlation between neuro-radiological, clinical and developmental data helps in making the correct diagnosis.

Core tip: Imaging of spinal dysraphism may appear complicated as it is a group of diverse conditions which can have variable imaging appearance. It includes a heterogeneous group of anomalies which result from faulty closure of midline structures during development. Magnetic resonance imaging is now considered the imaging modality of choice for diagnosing these conditions. A systematic approach and correlation with neuroradiological, clinical and developmental data helps in making the correct diagnosis.

- Citation: Kumar J, Afsal M, Garg A. Imaging spectrum of spinal dysraphism on magnetic resonance: A pictorial review. World J Radiol 2017; 9(4): 178-190

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1949-8470/full/v9/i4/178.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4329/wjr.v9.i4.178

Congenital malformations of spine and spinal cord are collectively termed as spinal dysraphism. It includes a heterogeneous group of anomalies resulting from incomplete midline closure of osseous, mesenchymal and nervous tissue[1]. Most of these conditions are diagnosed at or soon after birth, but some are discovered late in childhood or in adulthood because of absence of clinical manifestations. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is the imaging modality of choice for diagnosing spinal dysraphism because of its superior soft tissue characterisation and multiparametric imaging capabilities[2]. The purpose of this article is to review the normal development of spinal cord and MRI features of spinal dysraphism with clinico-embryologic and radiological correlation.

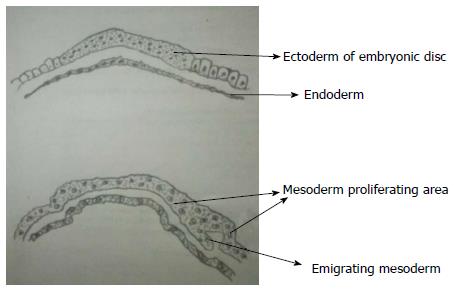

Development of spinal cord occurs during early embryogenesis (between 2-6 wk of gestation) in three main stages - gastrulation, primary neurulation and secondary neurulation[3,4]. During the stage of gastrulation, the bilaminar embryonic disc composed of ectoderm and endoderm is converted to a trilaminar disc by the formation of mesoderm (Figure 1).

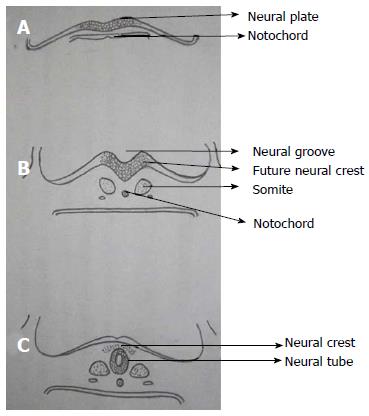

Notochord which is formed from midline mesoderm interacts with overlying ectoderm resulting in the formation of neuroectoderm and neural plate[5]. Primary neurulation begins with the formation of neural plate and ends with the closure of caudal end of neural plate (Figure 2). A small depression develops along the central axis of neural plate to form neural groove and neural folds are formed on both sides of the neural groove. The neural plate then bends and neural folds fuse together converting the linear neural plate into a cylindrical neural tube. Closure of neural groove proceeds bidirectionally with the cephalic end (anterior or rostral neuropore) closing on day 25 and the caudal end (posterior or caudal neuropore) closing on day 27 or 28[6].

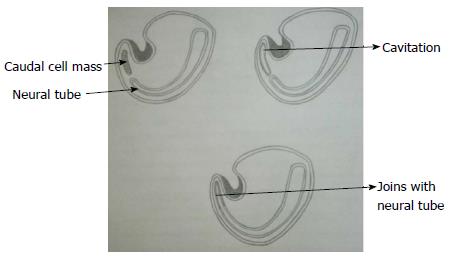

During secondary neurulation there is formation of caudal cell mass composed of undifferentiated pluripotent cells from the caudal end of neural tube and notochord distal to caudal neuropore. Neurons and vacuoles develop within the caudal cell mass. Vacuoles then coalesce and eventually connect to the central canal by the process called cavitation. Finally the cells of caudal cell mass undergo retrograde differentiation during which cells undergo programmed cell death or apoptosis to form conus medullaris, filum terminale and ventriculus terminalis (Figure 3)[7,8].

Various disorders due to defective primary neurulation include open spinal dysraphism (OSD), closed spinal dysraphism (CSD) and dorsal dermal sinus while defects during secondary neurulation results in filar lipoma, tight filum terminale, caudal agenesis and sacrococcygeal teratoma. Defective development of notochord results in diastematomyelia, neurenteric cyst, caudal agenesis and segmental spinal dysgenesis[9].

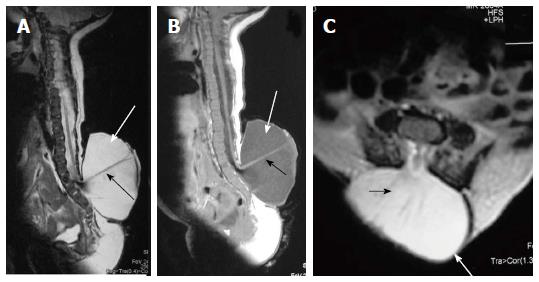

On the basis of presence or absence of overlying skin covering, spinal dysraphism is divided into open and closed types[10-12] (Table 1). In OSD overlying skin covering is absent and the neural elements are exposed to the external environment whereas, in closed type the neural elements have a skin covering (Figure 4). CSD can be further divided based on the presence or absence of associated subcutaneous mass.

| Open spinal dysraphisms |

| Myelomeningocele |

| Myelocele |

| Hemimyelomeningocele |

| Hemimyelocele |

| Closed spinal dysraphisms |

| With subcutaneous mass |

| Lipomyelomeningocele |

| Lipomyelocele |

| Terminal myelocystocele |

| Meningocele |

| Myelocystocele |

| Without subcutaneous mass |

| Simple dysraphic states |

| Intradural lipoma |

| Filar lipoma |

| Tight filum terminale |

| Persistent terminal ventricle |

| Dermal sinus |

| Complex dysraphic states |

| Dorsal enteric fistula |

| Neuroenteric cyst |

| Diastematomyelia |

| Caudal agenesis |

| Segmental spinal dysgenesis |

In our review, we will follow the clinic-radiological classification as it is easier to understand and is more prevalent in use.

OSDs result from faulty primary neurulation due to defective closure of the neural tube. About 98.8% of all OSDs are constituted by Myelomeningocele (MMC) where both the neural placode and meningeal lining protrude through the bony and cutaneous defect in the midline[3]. OSDs are commonly diagnosed clinically as the neonate presents with a midline reddish exposed neural placode and immediate surgical repair is usually done, so imaging studies are not always performed. It usually involves the lower lumbar and sacral regions (98%) and is rare in cervical and upper thoracic spine, probably because the lesion in these areas are more severe leading to fetal demise[4,13].

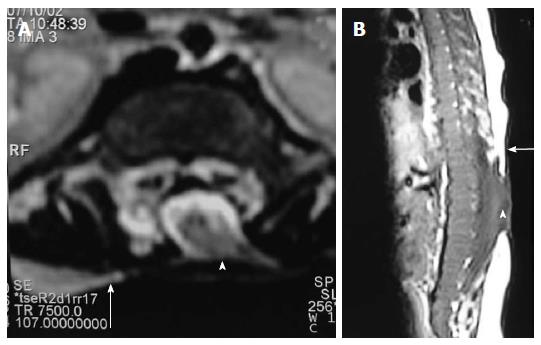

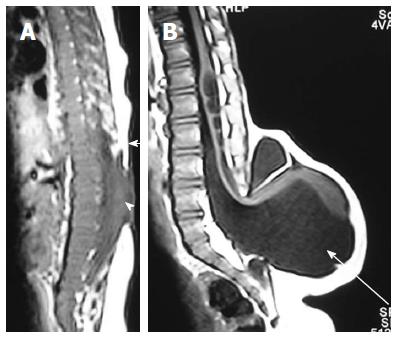

In MMC, the protruding neural placode extends beyond the skin surface as there is enlargement of the adjacent subarachnoid space (Figure 5)[5]. This help to distinguish MMC from the far rarer myelocele, where the placode is flush with the skin surface (Figures 6 and 7). About 80% of myelocele and MMC have associated hydrocephalus and 100% patients have Chiari II malformation which involve cerebellum, brain stem, skull base, spine and spinal column (Figure 8)[3,4]. Studies have shown that defective neural tube closure resulting in abnormal drainage of CSF and hence decompression of the primitive ventricular system resulting in various manifestations of Chiari II malformation[14,15].

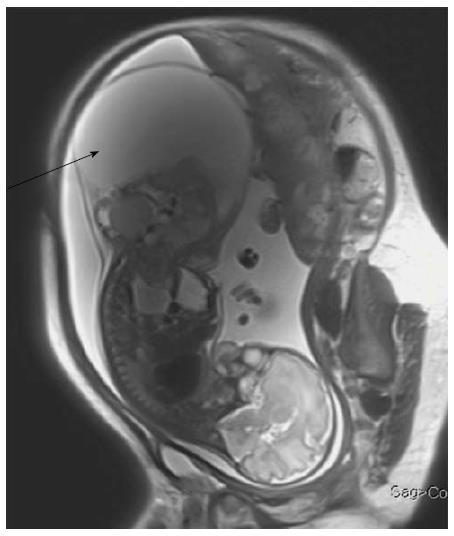

Advancements in prenatal diagnosis permit diagnosis of neural tube defects in fetus as early as first trimester, and now most of the cases of MMC are diagnosed prenatally during screening sonography. Although sonography is the modality of choice for screening fetus for any gross congenital anomalies, MRI is being increasingly used for prenatal evaluation of CNS anomalies with the advent of faster MR sequences (Figure 9)[16,17].

Prenatal diagnosis and developments in fetal surgery has made possible inutero repair of the neural tube defects which can arrest the development of other malformations developing secondary to abnormal tube closure. The Management of Myelomeningocele Study trial, a prospective randomized study done in United States has shown that fetal surgery for MMC in second trimester preserves neurologic function, reverses the changes of Chiari II malformation and reduces the need for postnatal ventriculoperitoneal shunt[18-21].

These conditions are extremely rare and are caused by defective gastrulation and primary neurulation[22]. Diastematomyelia is a common association with OSDs but only when one of the hemicords shows defective neurulation, the malformation is labelled hemimyelo(meningo)cele[3]. Here one of the two hemicords exhibits a myelomeningocele or myelocele while the other hemicord can be normal or is tethered.

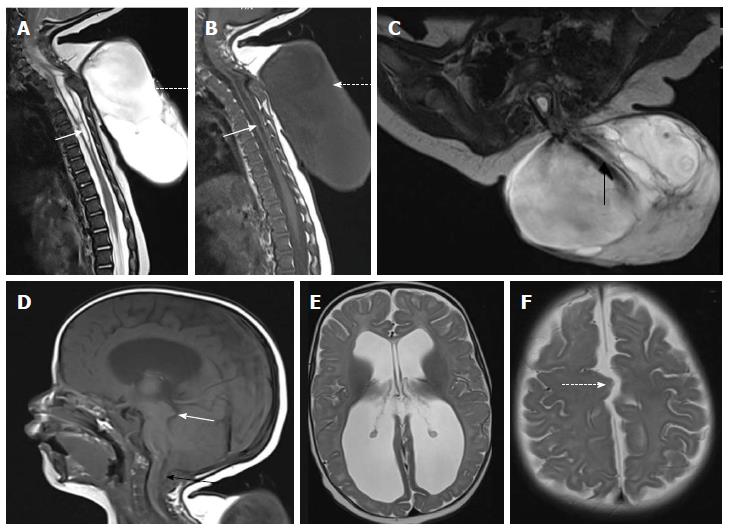

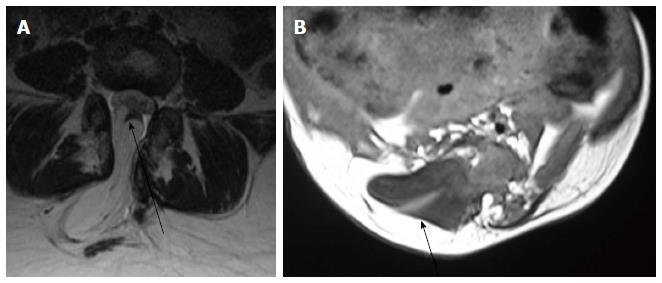

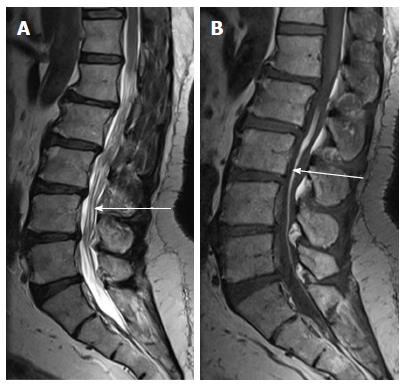

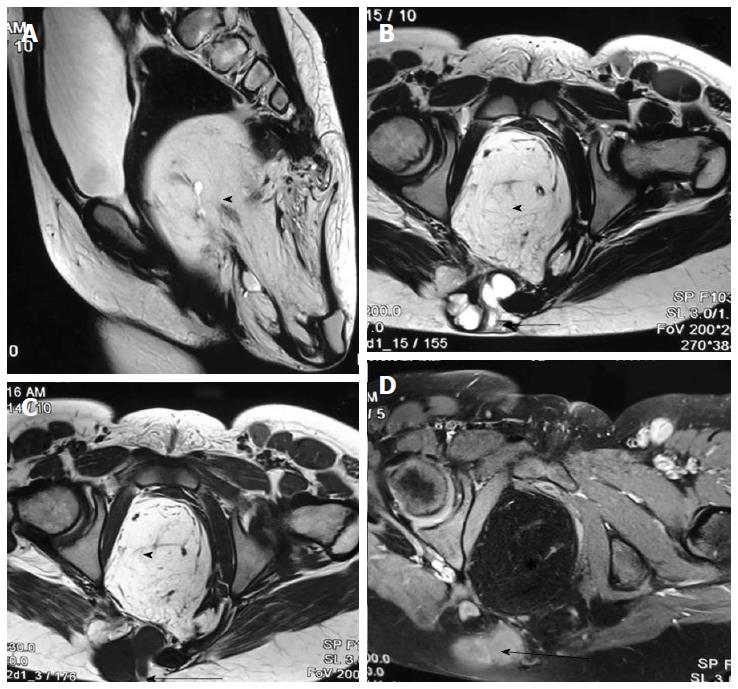

Lipomyelocele and Lipomyelomeningocele result from defective primary neurulation where there is premature focal disjunction of cutaneous ectoderm and neuroectoderm allowing mesenchyme to enter the neural tube. This mesenchyme later forms the lipomatous tissue for unknown reasons[23,24]. Clinically they are characterized by the presence of subcutaneous fatty mass lesion above the intergluteal line which may extend to buttocks. Sagittal T1 WI images show high intensity fat on the dorsal aspect of the placode which is continuous with the adjacent subcutaneous fat. T1 weighted fat saturated images show suppression of fat signal. Lipomyelocele and Lipomyelomeningocele are differentiated based on the position of neural placode - lipoma interface (Figure 10). It lies within or at the edge of the spinal canal in lipomyelocele and outside the spinal canal in lipomyelomeningocele (Figure 11)[11]. In lipomyelomeningocele there is expansion of subarachnoid space anterior to the cord pushing the neural placode - lipoma interface posteriorly to lie outside the boundaries of spinal canal. In hemilipomyelocele or hemilipomyelomeningocele there is associated diastematomyelia with one of the hemicord showing lipomyelocele or lipomyelomeningocele respectively (Figure 12).

Meningocele refers to herniation of CSF filled sac lined by dura and arahnoid mater. The exact embryogenesis is unknown but is thought to be caused by ballooning of meninges due to CSF pulsation. By definition, spinal cord should not be seen within the meningocele but may be seen tethered to its neck. Meningocele may contain nerve roots and or filum terminale which usually appear hypertrophied.

Posterior meningocele is due to herniation of meningial lining through posterior spina bifida (Figure 13). It is usually lumbosacral in location but can be seen in other locations also. Anterior meningocele is almost always presacral in location[25].

Terminal myelocystocele involves herniation of a dilated terminal central canal forming terminal syringohydromyelia (syringocele) through a posterior vertebral defect into an expanded CSF filled dural sheath (meningocele). It results from defective secondary neurulation which affects the CSF flow dynamics. The inner terminal syrinx communicates with the central canal of the spinal cord and the outer meningocele is continuous with the spinal subarachnoid space. The syringocele and meningocele usually do not communicate with each other[26-28].

These are a heterogeneous group of conditions which arise due to abnormalities of primary and secondary neurulation and are the most common type of spinal dysraphism seen in older children[29]. Simple dysraphic states include intradural lipoma, filar lipoma, tight filum terminale, dermal sinus and persistent terminal ventricle.

It is a midline lipoma located in the groove of unopposed neural placode in its dorsal surface within an intact dural sac. The intact dura help to differentiate this from lipomyelocele and lipomyelomeningocele. They are usually seen in lumbosacral region and are associated with tethered cord syndrome. Large lipomas may cause cord displacement. On MRI lipomas follow the signal intensity of subcutaneous fat on all sequences (Figure 14)[10].

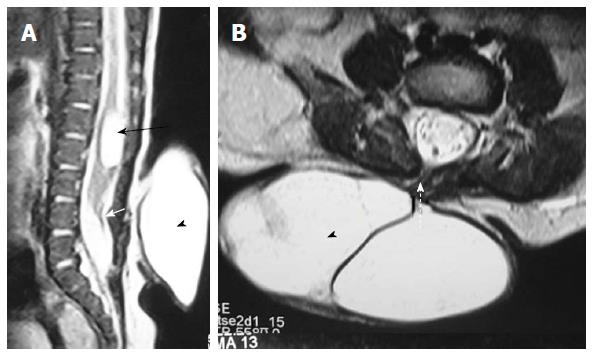

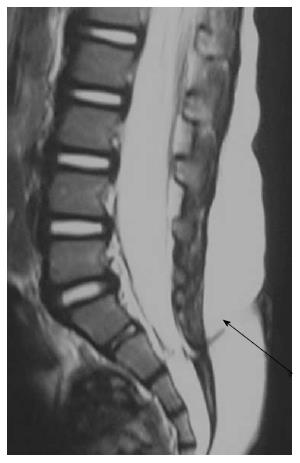

Filar lipoma is an abnormality of secondary neurulation which shows fibrolipomatous thickening of the filum terminale. On imaging filar lipoma appears hyperintense on T1 and T2 weighted images within a thickened filum terminale (Figure 15). One point five percent to 5% of normal adult population may show fat within filum terminale on MRI and hence the finding is considered a normal variant (Figure 16) unless it is associated with tethered cord syndrome[30,31]. Tethered cord syndrome is characterized clinically by progressive neurological deficit and on imaging, there is low lying conus medullaris with a short thick filum terminale which is tethered to dural sac[32].

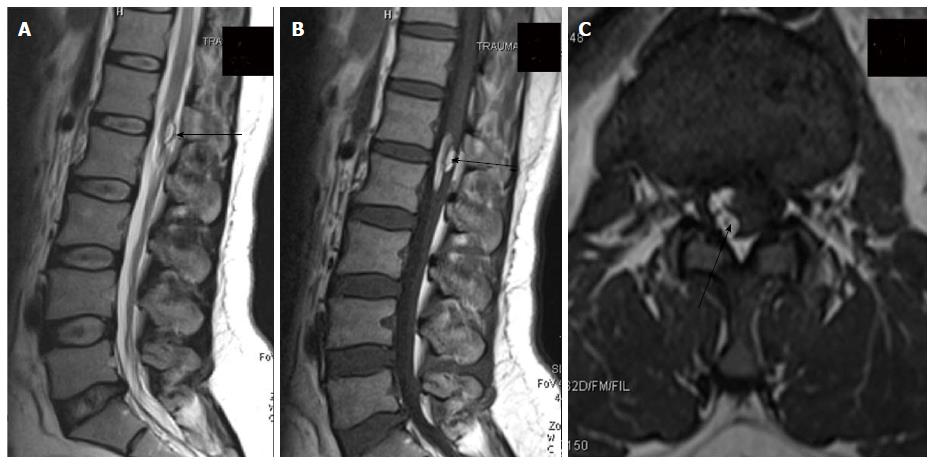

It is characterized by shortening and hypertrophy offilum terminale which cause tethering of cord and impairs the ascent of conus medullaris. Embryologically the defect lies in retrogressive differentiation during secondary neurulation.

On imaging it is characterized by a thick filum terminale (thickness measuring > 2 mm) and a low lying conus medullaris - below L2 vertebral body (Figure 17)[8]. It is usually seen in association with other malformations and isolated cases are rare.

It is an epithelial lined fistulous communication between CNS or its meningeal covering and skin. It results from focal incomplete disjunction between neuroectoderm and cutaneous ectoderm.

Clinically a midline dimple or ostium is found on the cutaneous surface and is commonly associated with cutaneous stigmata of underlying occult spinal dysraphism like hairy nevus, hemangioma or hyperpigmentation. The tract then ascends and opens into spinal canal (Figure 18). Dermal sinus may be associated with intraspinal dermoids or epidermoids which show variable imaging findings depending on their contents[33,34]. Dermoids usually appear hyperintense on both T1 and T2 weighted images while epidermoids are hypointense on T1 weighted and hyperintense on T2 weighted images. CNS infection is a common complication because of fistulous communication and hence these cases require early surgical repair (Figure 19).

Terminal ventricle is a small, ependyma lined cavity within conus medullaris (Figures 13 and 17). Embroyologically incomplete regression of terminal ventricle during the stage of secondary neurulation is responsible for the condition. Location just above filum terminale helps to differentiate it from hydromyelia and lack of enhancement is the differentiating feature from intramedullary tumors[35].

Any abnormality occurring at the time of gastrulation affects the spinal cord and various other structures which are derived from notochord resulting in complex anomalies[36]. Most of these abnormalities are covered by skin and subcutaneous masses are absent. On the basis of their embryogenesis complex dysraphic states are divided into two subtypes - disorders of midline notochordal integration and disorders of notochordal formation.

The process of fusion of paired notochordal anlagen to form a single midline notochordal process is called midline notochordal integration[3]. Any abnormality at this stage results in longitudinal splitting of spinal cord. Most important entities in this group are neurenteric cyst and diastematomyelia.

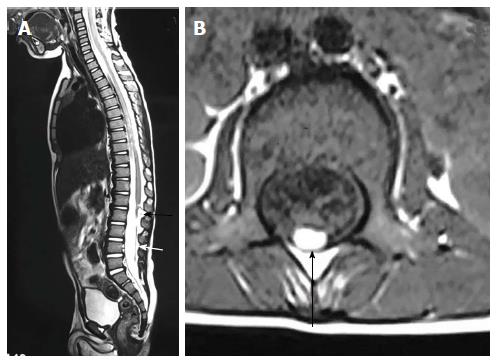

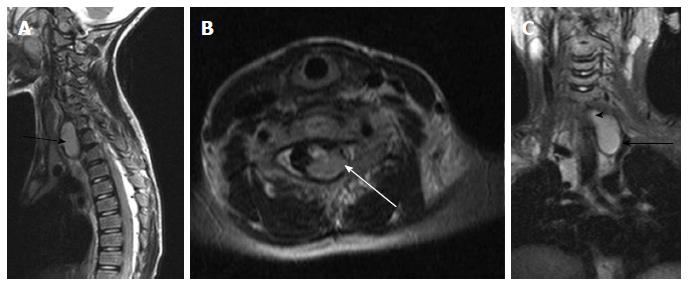

Neurenteric cyst: Most severe form of disorder of midline notochordal integration is dorsal enteric fistula - a fistulous communication between skin surface and bowel - which is an extremely rare condition. Neurenteric cyst is a localized form of dorsal enteric fistula and is seen anterior to spinal cord with adjacent vertebral anomalies. These cysts are typically seen in extramedullary intradural compartment of cervicothoracic spine, however may be seen in other locations too[37]. On MRI, neurenteric cysts usually appear iso- to hyper-intense to CSF on both T1 and T2 weighted images due to high protein content and show absent contrast enahncment (Figure 20)[38,39].

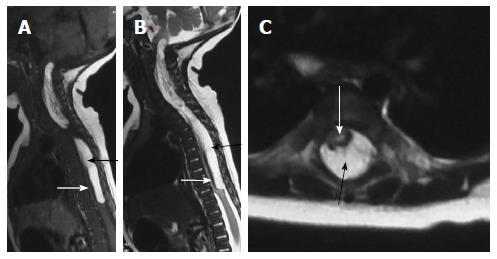

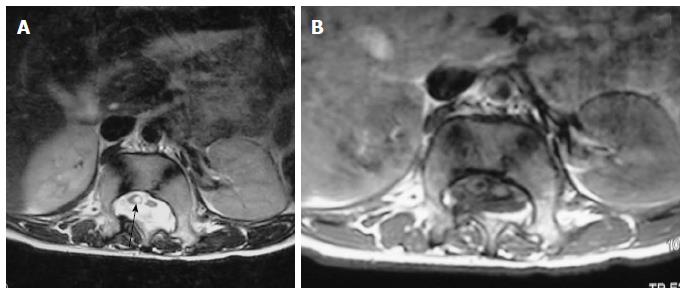

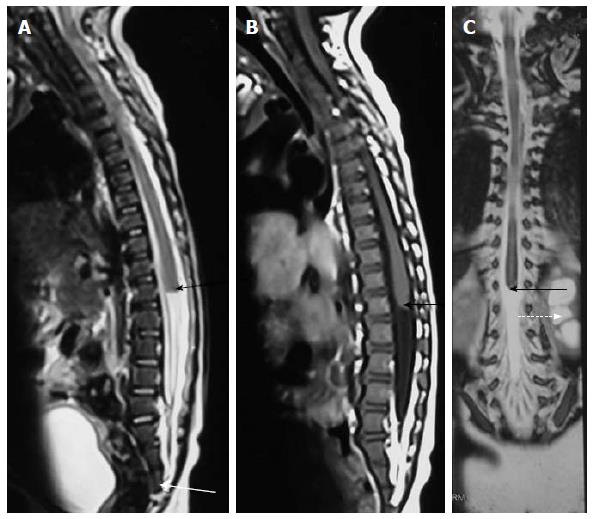

Diastematomyelia: It is the most common form of defective midline notochordal integration. Due to defective midline integration there are two notochordal processes each of which induces formation of separate neural plate with intervening primitive streak tissue. The development of the primitive streak tissue decides the type of diastematomyelia. In type I diastematomyelia the intervening primitive streak develops into bone or cartilage, resulting in two hemicords in different dural sacs separated by an osteocartilaginous septum (Figure 12). In type II diastematomyelia, the primitive streak is reabsorbed or forms a fibrous septum with the hemicords lying within the same dural sac (Figure 21)[40]. Diastematomyelia is commonly associated with vertebral anomalies and hydromyelia. A high lying hairy tuft over a child’s back is a reliable indicator for underlying diastematomyelia[41].

Apoptosis or programmed cell death is an important process occurring during different steps of embryogenesis. Abnormal apoptosis results in disorders of notochord formation and these disorders include caudal agenesis and segmental spinal dysgenesis[29].

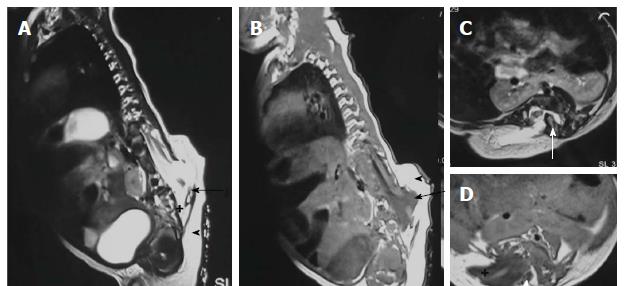

Caudal agenesis: It is characterized by partial or total agenesis of spinal column and is commonly associated with genital anomalies, anal imperforation, pulmonary hypoplasia, renal aplasia or dysplasia and limb abnormalities. Caudal agenesis (CA) is broadly divided into two types.

In type I CA both caudal cell mass and notochord formation is affected, resulting in high position (most commonly at the level of D12 vertebra) and abnormal termination of conus medullaris. There is accompanying varying degree of vertebral aplasia, with the last vertebra as L5 through S2 in majority of patients.

In type II CA there is abnormal development of only caudal cell mass with unaffected true notochord formation.Hence, there is defective secondary neurulation with normal primary neurulation. As a result only the most caudal part of conus medullaris is absent in type II CA (Figure 22). Vertebral dysgenesis is less severe in these cases and these patients present with tethered cord syndrome as the conus in these cases is stretched and tethered[42,43].

Segmental spinal dysgenesis: This is an extremely rare condition characterized by: (1) segmental agenesis or dysgenesis of lumbar or thoacolumbar spine; (2) segmental abnormality of spinal cord or nerve roots; (3) congenital pareparesis or paraplegia; and (4) congenital lower limb deformities. This occurs due to notochordal abnormality occurring during gastrulation which involves an intermediate segment of notochord[29,44].

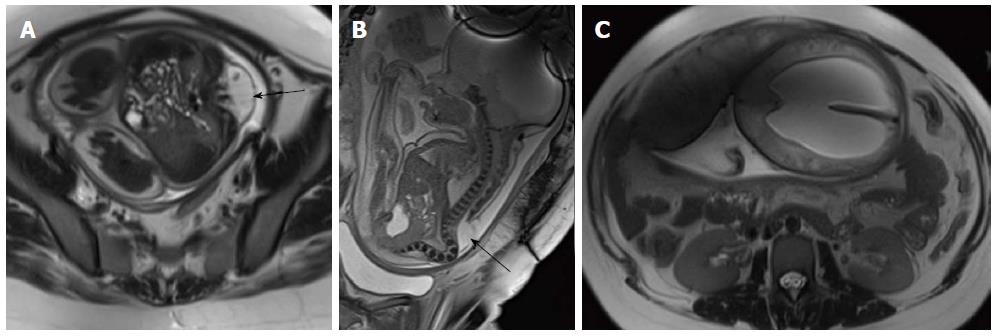

Sacrococcygeal teratoma, although a tumor, needs special mentioning as it develops from the pleuripotent cells of caudal cell mass. It is the most common tumor of fetus and new born and commonly present as a large complex solid cystic mass caudal to coccyx. Most of the teratomas are benign and contains derivatives from all three germ layers. Based on the presence of external and internal components they are divided into four types - type I: Primarily external, type II: Equal external and internal portions, type III: Primarily internal and type IV: Entirely internal.

On MRI, sacrococcygeal teratoma has variable signal on T1 and T2 weighted images depending on the internal contents (fat, soft tissue, fluid, calcium). On post contrast images, there is heterogeneous enhancement of the solid portion (Figure 23)[45,46]. This may also be picked up on antenatal scan where MRI can accurately depict its extension into the pelvis and its mass effect on pelvic organs (Figure 24).

Surgery is the treatment of choice for spinal dysraphism and surgery includes closure of the neural tube defect and detethering followed by lifelong supportive care and follow up. During follow-up, worsening of symptoms should be looked for and MRI should be done at the earliest suspicion. During post-operative imaging, various immediate and late complications of spinal surgery like wound infection, shunt infection, wound dehiscence, cerebrospinal fluid leak, problems related to kyphectomy, adhesions with retethering or dermoid formation should be looked for (Figure 25). Retethering is due to post-surgical fibrosis resulting in tethering of cauda equine fibres. MRI may be done in prone position to look for CSF dorsal to the conus for ruling out retethering[47].

Imaging of spinal dysraphism may appear complicated as it is a group of diverse conditions which can have variable imaging appearance. A systematic approach and correlation with neuroradiological, clinical and developmental data helps in making the correct diagnosis.

Manuscript source: Invited manuscript

Specialty type: Radiology, nuclear medicine and medical imaging

Country of origin: India

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C, C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P- Reviewer: Battal B, Doglietto F S- Editor: Ji FF L- Editor: A E- Editor: Wu HL

| 1. | French BN. The embryology of spinal dysraphism. Clin Neurosurg. 1983;30:295-340. [PubMed] |

| 2. | Rossi A, Cama A, Piatelli G, Ravegnani M, Biancheri R, Tortori-Donati P. Spinal dysraphism: MR imaging rationale. J Neuroradiol. 2004;31:3-24. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 58] [Cited by in RCA: 48] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Tortori-Donati P, Rossi A, Cama A. Spinal dysraphism: a review of neuroradiological features with embryological correlations and proposal for a new classification. Neuroradiology. 2000;42:471-491. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 263] [Cited by in RCA: 218] [Article Influence: 8.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Barkovich AJ. Pediatric neuroradiology, 4th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Willims & Wilkins 2011; 857-916. |

| 5. | Naidich TP, Blaser SI, Delman BN. Congenital Anomalies of the Spine and Spinal Cord: Embryology and Malformations. Magnetic Resonance Imaging of the Brain and Spine, 4th ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins 2009; 1364-1447. |

| 6. | Müller F, O’Rahilly R. The first appearance of the neural tube and optic primordium in the human embryo at stage 10. Anat Embryol (Berl). 1985;172:157-169. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 62] [Cited by in RCA: 44] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Catala M. Genetic control of caudal development. Clin Genet. 2002;61:89-96. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 58] [Cited by in RCA: 49] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Warder DE. Tethered cord syndrome and occult spinal dysraphism. Neurosurg Focus. 2001;10:e1. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 72] [Cited by in RCA: 82] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Huisman TA, Rossi A, Tortori-Donati P. MR imaging of neonatal spinal dysraphia: what to consider? Magn Reson Imaging Clin N Am. 2012;20:45-61. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Tortori-Donati P, Rossi A, Biancheri R, Cama A. Magnetic resonance imaging of spinal dysraphism. Top Magn Reson Imaging. 2001;12:375-409. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 77] [Cited by in RCA: 52] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Rossi A, Biancheri R, Cama A, Piatelli G, Ravegnani M, Tortori-Donati P. Imaging in spine and spinal cord malformations. Eur J Radiol. 2004;50:177-200. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 90] [Cited by in RCA: 82] [Article Influence: 3.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Thompson D. Spinal dysraphic anomalies; classification, presentation and management. Paediatrics and Child Health. 2010;20:397-403. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Osaka K, Matsumoto S, Tanimura T. Myeloschisis in early human embryos. Childs Brain. 1978;4:347-359. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | McLone DG, Naidich TP. Developmental morphology of the subarachnoid space, brain vasculature, and contiguous structures, and the cause of the Chiari II malformation. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 1992;13:463-482. [PubMed] |

| 15. | McLone DG, Knepper PA. The cause of Chiari II malformation: a unified theory. Pediatr Neurosci. 1989;15:1-12. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 353] [Cited by in RCA: 293] [Article Influence: 8.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | von Koch CS, Glenn OA, Goldstein RB, Barkovich AJ. Fetal magnetic resonance imaging enhances detection of spinal cord anomalies in patients with sonographically detected bony anomalies of the spine. J Ultrasound Med. 2005;24:781-789. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 47] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Reddy UM, Filly RA, Copel JA. Prenatal imaging: ultrasonography and magnetic resonance imaging. Obstet Gynecol. 2008;112:145-157. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 125] [Cited by in RCA: 92] [Article Influence: 5.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Adzick NS, Thom EA, Spong CY, Brock JW, Burrows PK, Johnson MP, Howell LJ, Farrell JA, Dabrowiak ME, Sutton LN. A randomized trial of prenatal versus postnatal repair of myelomeningocele. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:993-1004. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1703] [Cited by in RCA: 1300] [Article Influence: 92.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Adzick NS. Fetal surgery for spina bifida: past, present, future. Semin Pediatr Surg. 2013;22:10-17. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 109] [Cited by in RCA: 90] [Article Influence: 7.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Adzick NS. Fetal surgery for myelomeningocele: trials and tribulations. Isabella Forshall Lecture. J Pediatr Surg. 2012;47:273-281. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 59] [Cited by in RCA: 48] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Grivell RM, Andersen C, Dodd JM. Prenatal versus postnatal repair procedures for spina bifida for improving infant and maternal outcomes. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;CD008825. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Parmar H, Patkar D, Shah J, Maheshwari M. Diastematomyelia with terminal lipomyelocystocele arising from one hemicord: case report. Clin Imaging. 2003;27:41-43. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Naidich TP, Blaser SI, Delman BN, McLone DG, Dias MS, Zimmerman RA, Raybaud CA, Birschansky SB, Altman NR, Braffman BH. Embryology of the spine and spinal cord. ASNR. 2002;3-13. |

| 24. | Naidich TP, McLone DG, Mutluer S. A new understanding of dorsal dysraphism with lipoma (lipomyeloschisis): radiologic evaluation and surgical correction. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1983;140:1065-1078. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 66] [Cited by in RCA: 54] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Lee KS, Gower DJ, McWhorter JM, Albertson DA. The role of MR imaging in the diagnosis and treatment of anterior sacral meningocele. Report of two cases. J Neurosurg. 1988;69:628-631. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 46] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Byrd SE, Harvey C, Darling CF. MR of terminal myelocystoceles. Eur J Radiol. 1995;20:215-220. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Peacock WJ, Murovic JA. Magnetic resonance imaging in myelocystoceles. Report of two cases. J Neurosurg. 1989;70:804-807. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 39] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | McLone DG, Naidich TP. Terminal myelocystocele. Neurosurgery. 1985;16:36-43. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 40] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Tortori-Donati P, Fondelli MP, Rossi A, Raybaud CA, Cama A, Capra V. Segmental spinal dysgenesis: neuroradiologic findings with clinical and embryologic correlation. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 1999;20:445-456. [PubMed] |

| 30. | Uchino A, Mori T, Ohno M. Thickened fatty filum terminale: MR imaging. Neuroradiology. 1991;33:331-333. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 47] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Brown E, Matthes JC, Bazan C, Jinkins JR. Prevalence of incidental intraspinal lipoma of the lumbosacral spine as determined by MRI. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 1994;19:833-836. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 70] [Cited by in RCA: 59] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | El-Hefnawy AS, Wadie BS. Effect of detethering on bladder function in children with myelomeningocele: Urodynamic evaluation. J Pediatr Neurosci. 2009;4:70-72. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Kanev PM, Park TS. Dermoids and dermal sinus tracts of the spine. Neurosurg Clin N Am. 1995;6:359-366. [PubMed] |

| 34. | Thompson DN. Spinal inclusion cysts. Childs Nerv Syst. 2013;29:1647-1655. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Coleman LT, Zimmerman RA, Rorke LB. Ventriculus terminalis of the conus medullaris: MR findings in children. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 1995;16:1421-1426. [PubMed] |

| 36. | Dias MS, Walker ML. The embryogenesis of complex dysraphic malformations: a disorder of gastrulation? Pediatr Neurosurg. 1992;18:229-253. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 111] [Cited by in RCA: 90] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Harris CP, Dias MS, Brockmeyer DL, Townsend JJ, Willis BK, Apfelbaum RI. Neurenteric cysts of the posterior fossa: recognition, management, and embryogenesis. Neurosurgery. 1991;29:893-897; discussion 897-898. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 71] [Cited by in RCA: 60] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | Simon JA, Olan WJ, Santi M. Intracranial neurenteric cysts: a differential diagnosis and review. Radiographics. 1997;17:1587-1593. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | Rufener S, Ibrahim M, Parmar HA. Imaging of congenital spine and spinal cord malformations. Neuroimaging Clin N Am. 2011;21:659-676, viii. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 40. | Pang D, Dias MS, Ahab-Barmada M. Split cord malformation: Part I: A unified theory of embryogenesis for double spinal cord malformations. Neurosurgery. 1992;31:451-480. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 388] [Cited by in RCA: 362] [Article Influence: 11.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 41. | Barkovich AJ, Edwards Ms, Cogen PH. MR evaluation of spinal dermal sinus tracts in children. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 1991;12:123-129. [PubMed] |

| 42. | Estin D, Cohen AR. Caudal agenesis and associated caudal spinal cord malformations. Neurosurg Clin N Am. 1995;6:377-391. [PubMed] |

| 43. | Rufener SL, Ibrahim M, Raybaud CA, Parmar HA. Congenital spine and spinal cord malformations--pictorial review. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2010;194:S26-S37. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 65] [Cited by in RCA: 47] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 44. | Zana E, Chalard F, Mazda K, Sebag G. An atypical case of segmental spinal dysgenesis. Pediatr Radiol. 2005;35:914-917. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 45. | Danzer E, Hubbard AM, Hedrick HL, Johnson MP, Wilson RD, Howell LJ, Flake AW, Adzick NS. Diagnosis and characterization of fetal sacrococcygeal teratoma with prenatal MRI. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2006;187:W350-W356. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 68] [Cited by in RCA: 72] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 46. | Kocaoglu M, Frush DP. Pediatric presacral masses. Radiographics. 2006;26:833-857. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 49] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 47. | Venkataramana NK. Spinal dysraphism. J Pediatr Neurosci. 2011;6:S31-S40. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 54] [Cited by in RCA: 50] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |