Published online Sep 28, 2016. doi: 10.4329/wjr.v8.i9.799

Peer-review started: February 27, 2016

First decision: May 13, 2016

Revised: June 12, 2016

Accepted: July 29, 2016

Article in press: August 1, 2016

Published online: September 28, 2016

Processing time: 216 Days and 2.2 Hours

In the cancer research field, the preferred method for evaluating the proliferative activity of cancer cells in vivo is to measure DNA synthesis rates. The cellular proliferation rate is one of the most important cancer characteristics, and represents the gold standard of pathological diagnosis. Positron emission tomography (PET) has been used to evaluate in vivo DNA synthetic activity through visualization of enhanced nucleoside metabolism. However, methods for the quantitative measurement of DNA synthesis rates have not been fully clarified. Several groups have been engaged in research on 4′-[methyl-11C]-thiothymidine (11C-4DST) in an effort to develop a PET tracer that allows quantitative measurement of in vivo DNA synthesis rates. This mini-review summarizes the results of recent studies of the in vivo measurement of cancer DNA synthesis rates using 11C-4DST.

Core tip: There is a continuous demand to measure in situ DNA synthesis rates in living human cancer. The thymidine derivative 4′-[methyl-11C] thiothymidine (11C-4DST) has the potential to visualize in vivo DNA synthesis rates with positron emission tomography (PET). To confirm whether 11C-4DST is a valid DNA synthesis marker, clinical and basic research is being conducted at several PET centers in Japan, European Union, and the United States. This mini-review summarizes the progress of recent studies involving the in vivo imaging of cancer DNA synthesis using 11C-4DST PET.

- Citation: Toyohara J. Evaluation of DNA synthesis with carbon-11-labeled 4′-thiothymidine. World J Radiol 2016; 8(9): 799-808

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1949-8470/full/v8/i9/799.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4329/wjr.v8.i9.799

The basic principle of DNA synthesis measurement using positron emission tomography (PET) and the rationale for tracer development for DNA synthesis imaging were extensively reviewed by Bading et al[1], and Toyohara et al[2], respectively.

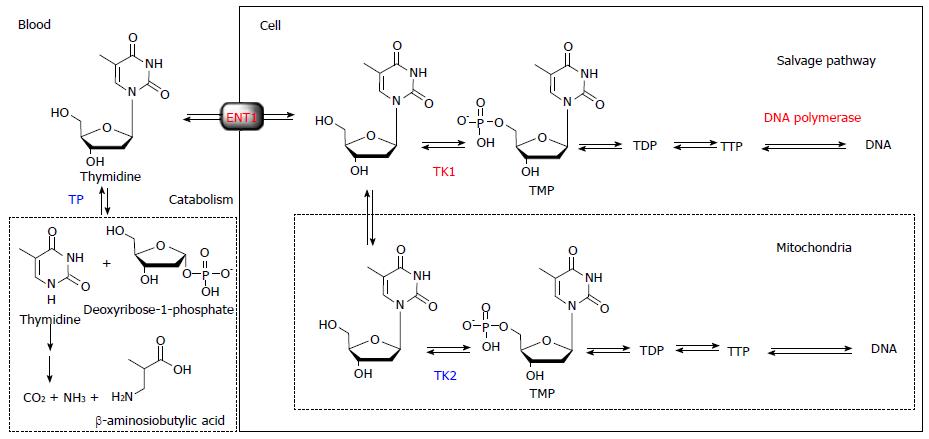

Briefly, thymidine is the only nucleoside that is exclusively incorporated into DNA. Therefore, DNA incorporation using [methyl-3H]-thymidine is used as the gold standard for a cell proliferation marker. The challenge in visualizing in vivo DNA synthesis with 11C-thymidine has been pursued since 1972[3]. Extensive developments in the 1990s and early 2000s realized the estimation of thymidine flux from blood to DNA in somatic and brain tumors[4-7]. From these studies, it became clear that the routine use of 11C-thymidine has several limitations, including issues related to the use of radiolabeled catabolites, the short half-life of 11C, and relatively difficult synthesis. While 11C-thymidine is effectively incorporated into DNA, it is also rapidly catabolized by thymidine phosphorylase, which complicates image analysis. Thymidine is a substrate for mitochondrial thymidine kinase 2 as well as cytosolic thymidine kinase 1, which leads to the absence of cell proliferation related uptake in tissues with high mitochondria content, such as the heart. Therefore, the ideal tracer for DNA synthesis imaging requires resistance to catabolism by thymidine phosphorylase, selective phosphorylation by thymidine kinase 1, and ready incorporation into DNA (Figure 1).

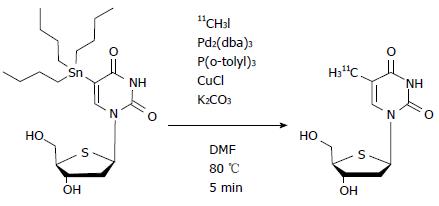

4′-[methyl-11C] thiothymidine (11C-4DST) is a derivative of thymidine in which the 4′-oxygen is replaced with sulfur and the 5-methyl group is radiolabeled with 11C by the C-C cross-coupling reaction (Figure 2)[8,9]. The first synthesis conditions reported involved using 5-tributylstannyl-4′-thio-2′-deoxyuridine (precursor)/tris (dibenzylideneacetone) dipalladium (0) [Pd2(dba)3]/tri(o-tryl) phosphine [P(o-CH3C6H4)3] (1.5:1:3.9 in molar ratio) at 130 °C for 5 min in N,N-dimethylformamide (DMF), which gave the desired products at only 30% decay-corrected yields based on [11C]CH3I[9]. Subsequently, slight modifications of the conditions, using precursor/Pd2(dba)3/P(o-CH3C6H4)3/CuCl/K2CO3 (1.5:1:3.9:4:3.6) at 80 °C, resulted in greatly improved decay-corrected yields (70%) based on [11C]CH3I[10]. Other reported conditions using precursor/Pd2(dba)3/P(o-CH3C6H4)3/CuCl/K2CO3 (25:1:32:2:5) at 80 °C also gave improved decay-corrected yields (42%-60%) using the two-pot method, and 65% by the one-pot method based on 11C-CH3I[11,12].

Preclinical evaluation indicated that the stability of 11C-4DST within the body is higher than that of thymidine, and unlike 3′-deoxy-3′-[18F]fluorothymidine (18F-FLT), it is taken up into DNA as a substrate for DNA synthesis. Therefore, Toyohara et al[8,9] postulated that 11C-4DST might be used as a valid in vivo DNA synthesis marker. 11C-4DST was developed at the National Institute of Radiological Sciences (NIRS; Chiba, Japan) and has been approved for clinical use by the committee for medical use of cyclotron-produced radiopharmaceuticals of NIRS, as well as the medical use of cyclotron-produced radiopharmaceuticals and ethics committees of Tokyo Metropolitan Institute of Gerontology (TMIG; Tokyo, Japan). The first-in-human study was performed at TMIG in March 2010. 11C-4DST was also described as 11C-S-dThd[8,9], however, the names have since been unified to 11C-4DST with the commencement of its clinical use[10].

An initial clinical trial of 11C-4DST, which was equivalent to a phase 1 trial, was performed according to guidelines approved in January 2008 by the institutional committee of TMIG for first-in-human use of novel radiopharmaceuticals. Briefly, five brain tumor patients volunteered to participate in a study of the side effects associated with administration of 11C-4DST, which were assessed by clinical symptoms, physical findings, and blood tests. Concurrently, 11C-4DST dynamic PET measurements were performed to assess the efficacy with which the desired function (DNA synthesis) can be measured. In addition, radiation dosimetry was estimated through whole-body PET measurement in three healthy volunteers.

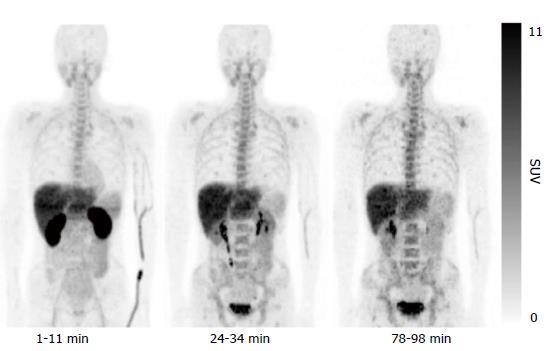

The results of the initial clinical trial revealed no adverse events accompanying administration of 11C-4DST, and the effective dose was calculated as 4.2 μSv/MBq. Whole-body PET indicated 11C-4DST accumulations in bone marrow and spleen, where DNA synthesis is active in the adult. These observations suggest that 11C-4DST uptake reflects the dynamics of DNA synthesis activity (Figure 3). In addition, physiological accumulation of radioactivity was observed in the liver, kidney, and salivary glands, which are components of the metabolic excretion pathway. The levels of 11C-4DST accumulation in the mediastinum, cerebral parenchyma, lungs, cardiac muscles, and skeletal muscles were very low.

The distribution of 11C-4DST within the human body was different from that in rodents, and a high level of 11C-4DST accumulation was observed in the human liver. This may have been due to species differences in 11C-4DST metabolism; the metabolism of 11C-4DST in humans is faster than that in rodents and produces hydrophilic metabolites. Treatment of the main component of the hydrophilic metabolites with β-glucuronidase results in the formation of 11C-4DST. Therefore, the high level of 11C-4DST accumulation in the human liver is due to conjugation of 11C-4DST.

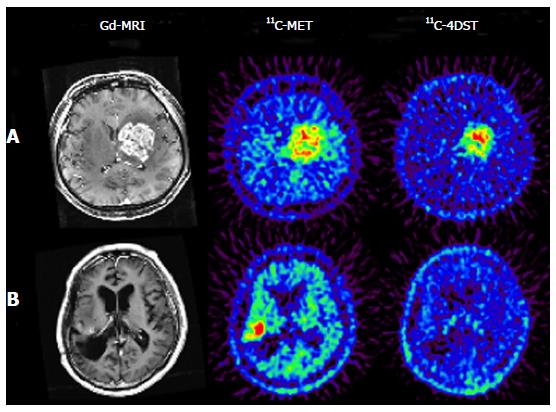

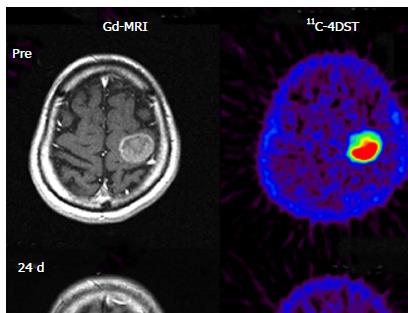

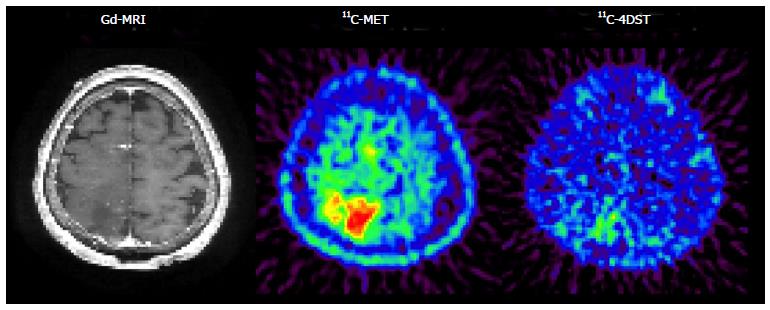

11C-4DST is a nucleoside derivative and therefore does not readily pass through the blood-brain barrier. Thus, accumulation of radioactivity in normal brain is low. However, the majority of brain tumor lesions could be imaged, and the accumulation of 11C-4DST in brain tumor lesions varied depending on the treatment conditions. In some cases, the accumulation of 11C-4DST was clearly different from 11C-methionine (11C-MET) images acquired at the same time. The images in Figure 4A shows a case that was resistant to the anticancer agent temozolomide, while the Figure 4B shows a case that was responsive to temozolomide. As can be seen in this figure, 11C-4DST sensitively captures the responsiveness of the tumor cells toward radiotherapy or chemotherapy.

Time-activity curves (TACs) of 11C-4DST accumulation in brain tumors indicated irreversible kinetics, suggesting that 11C-4DST might be metabolically trapped. In addition, Patlak graph analysis showed a linear plot, which supports the above suggestion[8,9]. The results of the preliminary kinetic analysis indicated that 11C-4DST was irreversibly taken up into the DNA because 11C-4DST fits the two-tissue three-compartment model, and k4 is negligibly small. The value of k3 (k4 = 0) obtained by the analysis showed a strong correlation with Ki (k4 = 0), which reflects the rate of 11C-4DST incorporation flux (Pearson’s r = 0.925, P = 0.001), and no correlation was observed with K1 (k4 = 0), which reflects intracellular transport. In addition, the standardized uptake value (SUV) showed the best correlation with Ki (Patlak) and also showed good correlations with Ki (k4 = 0) and k3 (k4 = 0) (Pearson’s r = 0.942, P = 0.0005; r = 0.857, P = 0.0065, respectively). The above results suggest that images of DNA synthesis might be obtained through non-quantitative analysis using SUV images.

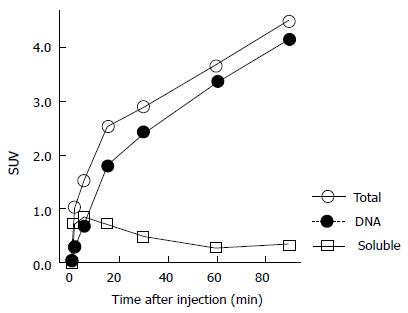

In addition, we performed a basic validation study of 11C-4DST accumulation kinetics into the DNA. The time course of the DNA uptake ratio in proliferating tissues in rats was illustrated by a Michaelis-Menten-type hyperbolic curve, and 50% of the radioactivity was taken into DNA at 5 and 8 min after administration in the duodenum and spleen, with maximum uptake ratios of 99% and 94%, respectively. The TACs of these tissues as a whole were almost identical to the TACs of DNA incorporated radioactivity (DNA fraction) and were different from the soluble non-DNA fraction (unchanged form + phosphorylated form) (Figure 5). On the other hand, in the AH109A rat liver cancer transplantation model, significant variation in DNA uptake rates between sampling sites was due to heterogeneity in the tumor tissues, with some regions exhibiting 60% DNA uptake at 1 min after administration (where cell proliferation is active). The above results indicate that the process of DNA uptake is the rate-limiting step in 11C-4DST accumulation.

Furthermore, Plotnik et al[13] evaluated the kinetics of 3H-4DST transport and metabolism in the human adenocarcinoma cell line A549 under exponential-growth conditions. 3H-4DST behaved qualitatively similar to endogenous thymidine in terms of equilibrative nucleoside transporter dependent cellular transport, shapes of cellular uptake curves, and relative DNA incorporation levels. As 4DST closely mimics thymidine metabolism, 11C-4DST should provide a robust measurement of DNA synthesis. However, overall 3H-4DST metabolism was significantly lower than that of thymidine, which may reflect its lower affinity toward thymidine kinase 1. This slower metabolism might limit its usefulness because of the relatively short half-life of the 11C label, especially in the case of slow-growing tumors like prostate cancer.

Although the presence of metabolites in blood was not desirable in terms of quantitative measurement, the results of the 11C-4DST early clinical trials indicated that its usability exceeded the drawbacks. In addition, as high usability of 11C-4DST was expected from the basic data obtained in animal experiments[8,9], collaborative research was initiated with the National Center for Global Health and Medicine (NCGM; Tokyo, Japan) and Kagawa University (Kagawa, Japan). In this collaborative research, technology transfer of radiosynthesis was first performed and then an application was submitted to the ethics committee. The clinical trial was started at approximately the same time as the early clinical trial performed at TMIG. A study to fundamentally support the clinical data is also being conducted in collaboration with the University of Groningen Medical Center (UMCG; Groningen, The Netherlands) and the University of Washington (Seattle, WA).

Initial clinical studies of 11C-4DST in brain tumors were performed at TMIG[14]. Fourteen patients with brain tumors (11 malignant gliomas, 2 metastatic tumors, 1 craniopharyngioma, and 1 malignant lymphoma) were included and the uptake of 11C-4DST and 11C-MET into gadolinium-enhanced lesions on T1 weighted magnetic resonance image (MRI) was evaluated. In this study, Nariai et al[14] observed a unique characteristic of 11C-4DST in one case. They observed a marked decrease of 11C-4DST uptake into metastatic lung cancer 5 d after gamma knife therapy. Although ring form enhancement with cystic formation did not disappear completely, tumor growth ceased with this treatment and the patient has maintained favorable activity of daily living 1 year after treatment (Figure 6). In another case, 11C-4DST could differentiate oligodendroglioma from malignant transformation (Figure 7). However, 11C-MET showed increased uptake, which indicates malignant transformation. An increased microvessel surface of oligodendroglioma causes the increased uptake of 11C-MET despite low proliferation of the tumor cells. This case study suggests that 11C-4DST accumulates in growing tumors but not in tumors stabilized by treatment. 11C-4DST uptake into tumors was not influenced by increased transport from blood to tissue, as observed for 11C-MET.

Further in-depth research of 11C-4DST in brain tumors was conducted at Kagawa University. Toyota et al[15] directly compared 11C-4DST and 18F-FLT in the same subjects. Twenty patients with primary (n = 9) and recurrent (n = 11) gliomas underwent 11C-4DST and 18F-FLT PET/CT scans. In the normal brain, 11C-4DST uptake was significantly higher than 18F-FLT (SUVmean; 0.34 ± 0.06 vs 0.19 ± 0.04, P < 0.001 by paired t-test). Individual 11C-4DST SUVmax in the tumor was very similar to 18F-FLT. Therefore, the average tumor-to-normal tissue uptake (T/N) ratio of 18F-FLT in the tumor was significantly higher than that of 11C-4DST (10.55 ± 5.45 vs 5.96 ± 3.86, P < 0.001 by paired t test), resulting in better tumor visualization with 18F-FLT. Both of these tracers did not show significant differences in T/N ratio among different glioma grades. Linear regression analysis showed a significant correlation between proliferative activity indicated by the Ki-67 labeling index and the T/N ratios of 11C-4DST (r = 0.50, P < 0.05) and 18F-FLT (r = 0.55, P < 0.05). A highly significant correlation was observed between the individual T/N ratios of 11C-4DST and 18F-FLT (r = 0.79, P = 0.0001). These results indicate that the uptake pattern and uptake values of 11C-4DST in gliomas are similar to those of 18F-FLT. Two exceptions were observed, one non-enhanced primary diffuse astrocytoma and one recurrent glioblastoma with an oligodendroglioma component, in which only 18F-FLT could detect the tumor well, with 11C-4DST showing no and faint uptake in the tumor, respectively.

In a follow-up study, Tanaka et al[16] retrospectively evaluated 11C-4DST uptake in 23 patients with newly diagnosed gliomas, and correlated the results with the Ki-67 index and tumor grade in comparison with 11C-MET[16]. 11C-4DST PET/CT showed a slightly lower detection rate for gliomas than 11C-MET (87% vs 96%); however, the difference was not statistically significant. The tracer uptake for normal brain tissue of 11C-4DST was significantly lower than that of 11C-MET (0.48 ± 0.19 vs 1.52 ± 0.36, P < 0.001). The tracer uptake of 11C-4DST in the tumor was also significantly lower than that of 11C-MET (2.14 ± 1.58 vs 5.39 ± 2.22, P < 0.001). Therefore, no significant difference in T/N ratio or metabolic tumor volume (MTV: volume with a threshold of 40% of SUVmax) was observed between 11C-4DST and 11C-MET. A weak correlation was observed between 11C-4DST and Ki-67 index for SUVmax (r = 0.46, P < 0.03), for T/N ratio (r = 0.43, P < 0.05), and for MTV (r = 0.68, P < 0.001) and between 11C-MET MTV and Ki-67 index (r = 0.43, P < 0.04). Among them, the correlation coefficient between 11C-4DST MTV and Ki-67 index was the highest. There was a significant difference in SUVmax of 11C-4DST between grades II and IV (P < 0.03) and in MTV between grades II and IV (P < 0.0009) and grades III and IV (P < 0.02).

Ito et al[17] prospectively compared the diagnostic value of 11C-4DST PET/CT and 18F-FDG PET/CT in patients with head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (HNSCC)[17]. Thirty-eight patients with advanced HNSCC underwent 11C-4DST PET/CT and 18F-FDG PET/CT before treatment. All patients were followed for 13.5 ± 7.5 mo to monitor recurrence. The total lesion glycolysis (TLG) for 18F-FDG and total lesion proliferation (TLP) for 11C-4DST were used as outcome measures of the combination of functional information and volumetric data to predict patient prognosis[18-21]. Nine of the 38 patients with post-treatment recurrence were identified. Receiver operating characteristic curves for TLG3.0 (sensitivity: 89%; specificity: 72%) and TLP2.5 (sensitivity: 89%; specificity: 55%) showed the highest prognostic ability for recurrence. There was no significant correlation between the Ki-67 index and whether 18F-FDG SUVmax (P = 0.81) or 11C-4DST SUVmax (P = 0.49) was observed in the primary tumor. One possible reason for this finding may be that the Ki-67 index was obtained mainly from biopsy specimens, not from resected specimens.

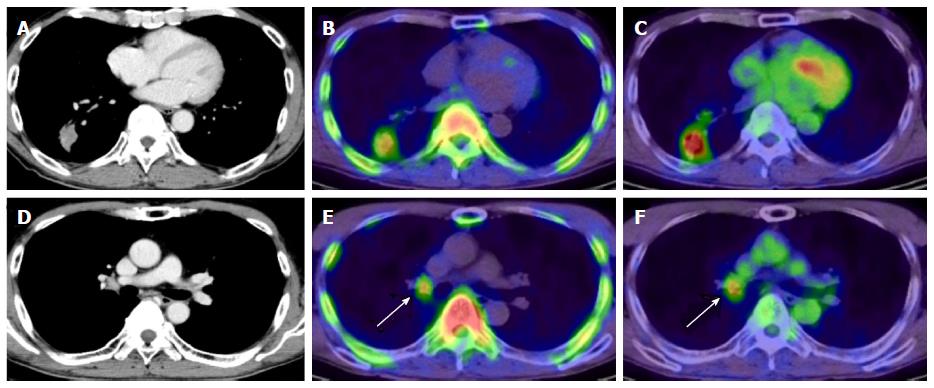

At NCGM, the first study focused mainly on lung cancer cases[22]. The subjects were 18 primary lung cancer patients (19 lesions) who underwent segmental resection and lymph node dissection. 18F-FDG PET/CT and 11C-4DST PET/CT were performed in these patients during the same period and SUVmax was measured at the lesioned region in each patient. The results and histopathological evaluation (e.g., Ki-67 index) were compared. The observed histological types included 16 adenocarcinomas (including bronchioloalveolar carcinoma), 2 squamous cell carcinomas, and 1 large cell carcinoma, and the average tumor size was 27.2 mm. The average levels of SUVmax in the primary tumors were 2.9 ± 1.0 and 6.2 ± 4.5 for 11C-4DST and 18F-FDG, respectively; SUVmax of 11C-4DST was approximately half that of 18F-FDG. Figure 8 shows representative images of 11C-4DST in patients with lung adenocarcinoma. 11C-4DST clearly visualized hilar lymph node metastasis because of low physiologic accumulation in the mediastinum blood pool. The correlation coefficients between SUVmax and Ki-67 index were 0.81 and 0.71 for 11C-4DST and 18F-FDG, respectively, and that of 11C-4DST was significantly higher. 11C-4DST appears to be effective as a PET tracer in primary lung cancer indicating DNA synthetic activity (cell proliferation activity).

The diagnostic ability of 11C-4DST for detecting regional lymph node metastasis of non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) was prospectively evaluated by the same group (NCGM)[23]. A total of 31 patients with NSCLC underwent 11C-4DST PET/CT and 18F-FDG PET/CT. Patients were followed for up to 2 years to assess disease-free survival. A total of 123 nodal groups were defined for 27 patients, with proven malignancy in 17 nodal groups of 9 patients. The sensitivity on a per-node basis was significantly higher with 11C-4DST than with 18F-FDG (82.5% vs 29.4%, P < 0.002). In contrast, the specificity on a per-node basis was significantly lower with 11C-4DST than with 18F-FDG (71.7% vs 85.8%, P < 0.02). The disease-free survival rate with positive 11C-4DST uptake in nodal lesions was 0.35, which was considerably lower than the rate of 0.83 with negative findings (P = 0.04). Interestingly, nodal staging by 11C-4DST was the most influential prognostic factor (P = 0.05) among the factors tested. The high sensitivity of 11C-4DST for nodal metastasis indicates that it may be efficient in detecting lymph node micrometastasis.

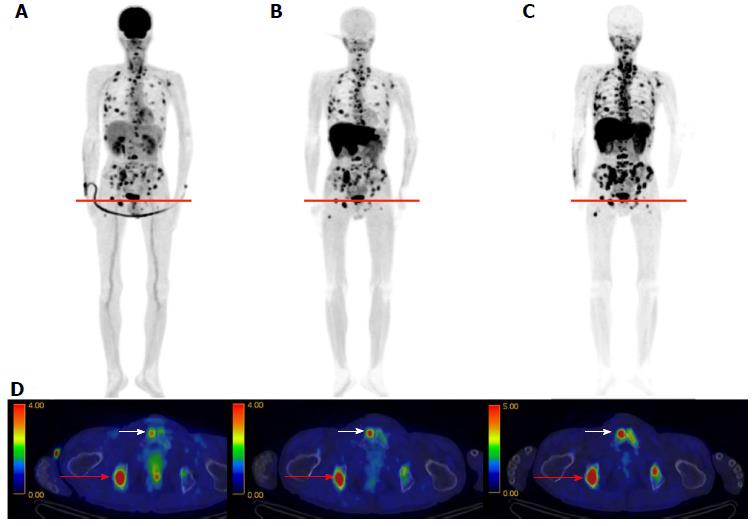

In whole-body imaging diagnosis of multiple myeloma (MM), it was demonstrated that myeloma has various characteristics that become prominent at different stages, including energy metabolism (18F-FDG), production of M protein (11C-MET), and cell proliferation (11C-4DST). We hope to be able to accurately determine the periods where follow-up observation is sufficient and aggressive chemotherapy is necessary, to optimize treatment in such cases. Okasaki et al[24] prospectively evaluated the possibility of 11C-MET and 11C-4DST whole-body PET/CT when searching for bone marrow involvement in patients with MM, in comparison with those for 18F-FDG PET/CT and aspiration cytology[24]. A total of 64 patients with MM or monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance (MUGS) underwent three whole-body PET/CT scans with 18F-FDG, 11C-MET, and 11C-4DST within a period of 1 wk. The tracer accumulation was evaluated as positive, equivocal, or negative for 55 lytic lesions visualized using CT in 24 patients. To verify tracer uptake by lesions, 36 patients underwent bone aspiration cytology within 1 wk of the three PET/CT scans. The SUVmax of 11C-4DST in lytic lesions were highest among the three tracers. 11C-4DST and 11C-MET provided clearer findings than 18F-FDG for lytic lesions. A typical MM patient with multiple active lesions is shown in Figure 9. 11C-MET and 11C-4DST detected positive lesions, whereas 18F-FDG detected an equivocal lesion. 18F-FDG was rarely able to detect skull lesions because of the high physiological accumulation in the brain, whereas 11C-MET and 11C-4DST were capable of clearly detecting skull lesions because of their low accumulation in the brain. Furthermore, 11C-4DST and 11C-MET had higher diagnostic accuracies than that of 18F-FDG, when compared with iliac crest biopsy. However, no significant difference was observed between the 11C-MET and 11C-4DST findings.

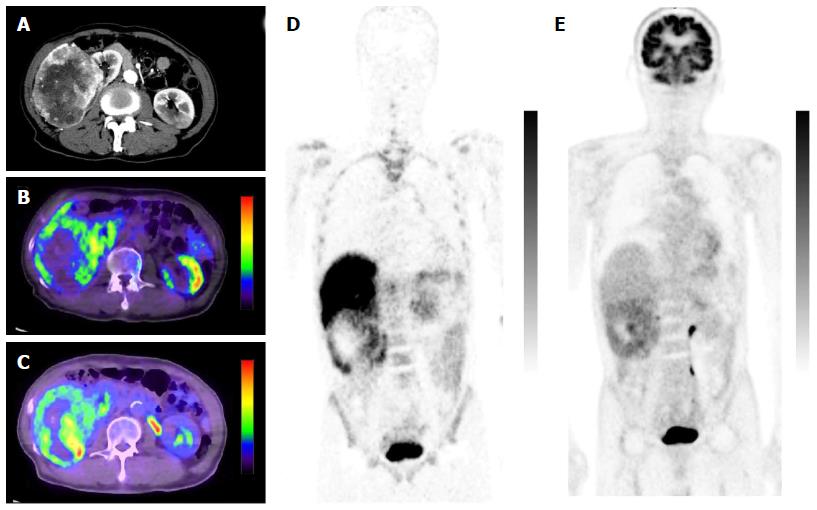

Minamimoto et al[25] evaluated the potential of 11C-4DST PET/CT for imaging cellular proliferation in advanced clear cell renal cell cancer (RCC), compared with 18F-FDG PET/CT[25]. Five patients with a single RCC lesion were examined. The typical tumor accumulation pattern of 18F-FDG was diffuse or with a thick uptake layer, in contrast to outer surface-dominant uptake with 11C-4DST (Figure 10). The SUVmax of 11C-4DST (7.3 ± 12.2) was slightly higher than that of 18F-FDG (6.0 ± 12.8). The correlation between SUVmax and Ki-67 index was higher with 11C-4DST (r = 0.61) than with 18F-FDG (r = 0.43). Tumor uptake of both tracers was correlated with the Fuhrman nuclear grading system. Interestingly, the 11C-4DST uptake increased as the degree of pathological phosphorylation of mammalian target of rapamycin (pmTOR) increased. This might indicate that 11C-4DST has potential for use in evaluating the therapeutic effect of mTOR inhibitors in patients with RCC.

In cancer, differential diagnosis of benign vs malignant lesions is important. Toyohara et al[26] investigated whether 4DST is useful for differentially diagnosing tumors and inflammation in animal models[26]. C6 glioma cells were transplanted into the right shoulder of Wistar rats, and turpentine was injected into the left hind leg 9 d later to create a tumor and acute inflammation model. Dynamic 11C-4DST PET scan was performed one day after turpentine injection. The biodistribution of 11C-4DST was determined and compared with those of 18F-FLT, 18F-FDG, 11C-choline, 11C-MET, and two sigma receptor ligands 1-4-2′-18F-fluoroethoxy-3-methoxyphenethyl-4-3-4-fluorophenyl-propyl-piperazine (18F-FE-SA5845) and 1-3,4-11C-dimethoxyphenylethyl-4-3-phenylpropyl-piperazine (11C-SA4503). The results showed that 11C-4DST had the highest tumor uptake among the tracers examined (SUV = 4.9), and the tumor muscle ratio was 13, which is equivalent to that of 18F-FDG. 11C-4DST showed an extremely high tumor inflammation ratio of 49, which was comparable to that of 18F-FE-SA5845, and was more than 10-fold higher than that of 18F-FDG. 11C-4DST showed a persistent increase in accumulation in the tumor and bone marrow. On the other hand, it was not retained in inflammatory tissues, and returned to the same level as in muscles 40 min after injection. As indicated here, 11C-4DST is a useful PET tracer with high sensitivity and specificity, with completely different dynamics in tumors and inflammatory tissue. The above results strongly suggest that 11C-4DST will be effective in clinical settings.

In a follow-up study, Toyohara et al[27] evaluated longitudinal changes in 11C-4DST uptake in turpentine-induced acute, subacute, and chronic phases of inflammatory tissues[27]. They found that 11C-4DST uptake in inflammatory tissue was transiently increased during the subacute phase and subsequently decreased to normal levels. The transient increase in 11C-4DST uptake paralleled changes in the Ki-67 labeling index in inflammatory tissues. These data indicate that avoiding the subacute phase is required for proper evaluation of tumor responses using 11C-4DST PET.

Tsuji et al[28] established a clinically relevant mouse model of mesothelioma[28] and applied 11C-4DST as a tool to differentiate histological subtypes. In their mouse model, 11C-4DST was suitable for imaging the epithelioid subtype, while 18F-FDG was more suitable for the sarcomatoid subtype.

Hasegawa et al[29] evaluated radiation induced carcinogenesis and its suppression by 11C-4DST PET in a radiation-induced thymic lymphoma model[29]. They found initial higher 11C-4DST uptake in irradiated thymus at 1 wk after fractionated whole-body X-ray irradiation. The increased 11C-4DST uptake in the thymus was completely abolished by bone marrow transplantation. This study demonstrates the feasibility of cellular proliferation imaging with 11C-4DST for the noninvasive monitoring of tumorigenic processes in animal models of radiation-induced cancer.

11C-4DST is a newly developed PET tracer that can be used to image DNA synthesis, and its application in clinical settings is being studied at several facilities. In the future, 11C-4DST will be applied to more types of cancer, which will further establish the significance of 11C-4DST PET diagnoses through the accumulation of data on the physiological accumulation in lesions.

The author thanks Mr. Kunpei Hayashi for the production of 11C-4DST. Figures 4, 6 and 7 were reprinted from Nariai et al[14], with the permission of Springer. Figures 3 and 8 were reprinted from Toyohara et al[10] and Minamimoto et al[22], respectively, with the permission of the Society of Nuclear Medicine and Molecular Imaging, Inc. Figures 9 and 10 were reprinted from Okasaki et al[24] and Minamimoto et al[25], respectively, with the permission of Springer.

Manuscript source: Invited manuscript

Specialty type: Radiology, nuclear medicine and medical imaging

Country of origin: Japan

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P- Reviewer: Chow J, Gao BL S- Editor: Qiu S L- Editor: Wang TQ E- Editor: Wu HL

| 1. | Bading JR, Shields AF. Imaging of cell proliferation: status and prospects. J Nucl Med. 2008;49 Suppl 2:64S-80S. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 243] [Cited by in RCA: 222] [Article Influence: 13.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Toyohara J, Fujibayashi Y. Trends in nucleoside tracers for PET imaging of cell proliferation. Nucl Med Biol. 2003;30:681-685. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Christman D, Crawford EJ, Friedkin M, Wolf AP. Detection of DNA synthesis in intact organisms with positron-emitting (methyl- 11 C)thymidine. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1972;69:988-992. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 105] [Cited by in RCA: 89] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Mankoff DA, Shields AF, Graham MM, Link JM, Eary JF, Krohn KA. Kinetic analysis of 2-[carbon-11]thymidine PET imaging studies: compartmental model and mathematical analysis. J Nucl Med. 1998;39:1043-1055. [PubMed] |

| 5. | Mankoff DA, Shields AF, Link JM, Graham MM, Muzi M, Peterson LM, Eary JF, Krohn KA. Kinetic analysis of 2-[11C]thymidine PET imaging studies: validation studies. J Nucl Med. 1999;40:614-624. [PubMed] |

| 6. | Wells JM, Mankoff DA, Eary JF, Spence AM, Muzi M, O’Sullivan F, Vernon CB, Link JM, Krohn KA. Kinetic analysis of 2-[11C]thymidine PET imaging studies of malignant brain tumors: preliminary patient results. Mol Imaging. 2002;1:145-150. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Wells JM, Mankoff DA, Muzi M, O’Sullivan F, Eary JF, Spence AM, Krohn KA. Kinetic analysis of 2-[11C]thymidine PET imaging studies of malignant brain tumors: compartmental model investigation and mathematical analysis. Mol Imaging. 2002;1:151-159. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Toyohara J, Kumata K, Fukushi K, Irie T, Suzuki K. Evaluation of 4’-[methyl-14C]thiothymidine for in vivo DNA synthesis imaging. J Nucl Med. 2006;47:1717-1722. [PubMed] |

| 9. | Toyohara J, Okada M, Toramatsu C, Suzuki K, Irie T. Feasibility studies of 4’-[methyl-(11)C]thiothymidine as a tumor proliferation imaging agent in mice. Nucl Med Biol. 2008;35:67-74. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 44] [Cited by in RCA: 44] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Toyohara J, Nariai T, Sakata M, Oda K, Ishii K, Kawabe T, Irie T, Saga T, Kubota K, Ishiwata K. Whole-body distribution and brain tumor imaging with (11)C-4DST: a pilot study. J Nucl Med. 2011;52:1322-1328. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Koyama H, Siqin Z, Sumi K, Hatta Y, Nagata H, Doi H, Suzuki M. Highly efficient syntheses of [methyl-11C]thymidine and its analogue 4’-[methyl-11C]thiothymidine as nucleoside PET probes for cancer cell proliferation by Pd(0)-mediated rapid C-[11C]methylation. Org Biomol Chem. 2011;9:4287-4294. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Zhang Z, Doi H, Koyama H, Watanabe Y, Suzuki M. Efficient syntheses of [¹¹C]zidovudine and its analogs by convenient one-pot palladium(0)-copper(I) co-mediated rapid C-[¹¹C]methylation. J Labelled Comp Radiopharm. 2014;57:540-549. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Plotnik DA, Wu S, Linn GR, Yip FC, Comandante NL, Krohn KA, Toyohara J, Schwartz JL. In vitro analysis of transport and metabolism of 4’-thiothymidine in human tumor cells. Nucl Med Biol. 2015;42:470-474. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Nariai T, Inaji M, Sakata M, Toyohara J. Use of 11C-4DST-PET for imaging human brain tumors. Tumors of the Central Nervous System, Volume 11. Netherlands: Springer 2014; 41-48. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Toyota Y, Miyake K, Kawai N, Hatakeyama T, Yamamoto Y, Toyohara J, Nishiyama Y, Tamiya T. Comparison of 4’-[methyl-(11)C]thiothymidine ((11)C-4DST) and 3’-deoxy-3’-[(18)F]fluorothymidine ((18)F-FLT) PET/CT in human brain glioma imaging. EJNMMI Res. 2015;5:7. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Tanaka K, Yamamoto Y, Maeda Y, Yamamoto H, Kudomi N, Kawai N, Toyohara J, Nishiyama Y. Correlation of 4’-[methyl-(11)C]-thiothymidine uptake with Ki-67 immunohistochemistry and tumor grade in patients with newly diagnosed gliomas in comparison with (11)C-methionine uptake. Ann Nucl Med. 2016;30:89-96. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Ito K, Yokoyama J, Miyata Y, Toyohara J, Okasaki M, Minamimoto R, Morooka M, Ishiwata K, Kubota K. Volumetric comparison of positron emission tomography/computed tomography using 4’-[methyl-¹¹C]-thiothymidine with 2-deoxy-2-18F-fluoro-D-glucose in patients with advanced head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Nucl Med Commun. 2015;36:219-225. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Koyasu S, Nakamoto Y, Kikuchi M, Suzuki K, Hayashida K, Itoh K, Togashi K. Prognostic value of pretreatment 18F-FDG PET/CT parameters including visual evaluation in patients with head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2014;202:851-858. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 61] [Cited by in RCA: 57] [Article Influence: 5.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Lim R, Eaton A, Lee NY, Setton J, Ohri N, Rao S, Wong R, Fury M, Schöder H. 18F-FDG PET/CT metabolic tumor volume and total lesion glycolysis predict outcome in oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma. J Nucl Med. 2012;53:1506-1513. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 137] [Cited by in RCA: 148] [Article Influence: 11.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Dibble EH, Alvarez AC, Truong MT, Mercier G, Cook EF, Subramaniam RM. 18F-FDG metabolic tumor volume and total glycolytic activity of oral cavity and oropharyngeal squamous cell cancer: adding value to clinical staging. J Nucl Med. 2012;53:709-715. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 175] [Cited by in RCA: 190] [Article Influence: 14.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Moon SH, Choi JY, Lee HJ, Son YI, Baek CH, Ahn YC, Park K, Lee KH, Kim BT. Prognostic value of 18F-FDG PET/CT in patients with squamous cell carcinoma of the tonsil: comparisons of volume-based metabolic parameters. Head Neck. 2013;35:15-22. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 92] [Cited by in RCA: 100] [Article Influence: 7.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Minamimoto R, Toyohara J, Seike A, Ito H, Endo H, Morooka M, Nakajima K, Mitsumoto T, Ito K, Okasaki M. 4’-[Methyl-11C]-thiothymidine PET/CT for proliferation imaging in non-small cell lung cancer. J Nucl Med. 2012;53:199-206. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Minamimoto R, Toyohara J, Ito H, Seike A, Miyata Y, Morooka M, Okasaki M, Nakajima K, Ito K, Ishiwata K. A pilot study of 4’-[methyl-11C]-thiothymidine PET/CT for detection of regional lymph node metastasis in non-small cell lung cancer. EJNMMI Res. 2014;4:10. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Okasaki M, Kubota K, Minamimoto R, Miyata Y, Morooka M, Ito K, Ishiwata K, Toyohara J, Inoue T, Hirai R. Comparison of (11)C-4’-thiothymidine, (11)C-methionine, and (18)F-FDG PET/CT for the detection of active lesions of multiple myeloma. Ann Nucl Med. 2015;29:224-232. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Minamimoto R, Nakaigawa N, Nagashima Y, Toyohara J, Ueno D, Namura K, Nakajima K, Yao M, Kubota K. Comparison of 11C-4DST and 18F-FDG PET/CT imaging for advanced renal cell carcinoma: preliminary study. Abdom Radiol (NY). 2016;41:521-530. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Toyohara J, Elsinga PH, Ishiwata K, Sijbesma JW, Dierckx RA, van Waarde A. Evaluation of 4’-[methyl-11C]thiothymidine in a rodent tumor and inflammation model. J Nucl Med. 2012;53:488-494. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Toyohara J, Sakata M, Oda K, Ishii K, Ishiwata K. Longitudinal observation of [11C]4DST uptake in turpentine-induced inflammatory tissue. Nucl Med Biol. 2013;40:240-244. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Tsuji AB, Sogawa C, Sugyo A, Sudo H, Toyohara J, Koizumi M, Abe M, Hino O, Harada YN, Furukawa T. Comparison of conventional and novel PET tracers for imaging mesothelioma in nude mice with subcutaneous and intrapleural xenografts. Nucl Med Biol. 2009;36:379-388. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Hasegawa S, Morokoshi Y, Tsuji AB, Kokubo T, Aoki I, Furukawa T, Zhang MR, Saga T. Quantifying initial cellular events of mouse radiation lymphomagenesis and its tumor prevention in vivo by positron emission tomography and magnetic resonance imaging. Mol Oncol. 2015;9:740-748. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Lu L, Bergström M, Fasth KJ, Langström B. Synthesis of [76Br]bromofluorodeoxyuridine and its validation with regard to uptake, DNA incorporation, and excretion modulation in rats. J Nucl Med. 2000;41:1746-1752. [PubMed] |