Peer-review started: August 18, 2014

First decision: September 28, 2014

Revised: December 22, 2014

Accepted: February 10, 2015

Article in press: February 12, 2015

Published online: March 28, 2015

Processing time: 218 Days and 16 Hours

Henoch-Schonlein purpura (HSP) is a small vessel vasculitis mediated by type III hypersensitivity with deposition of IgA immune complex in the walls of vessels. It is a multi-system disorder characterized by palpable purpura, arthritis, glomerulonephritis and gastrointestinal manifestations and commonly occurs in children and young adults. The patients with gastrointestinal involvement usually present with colicky abdominal pain, vomiting and melena. The imaging findings include multifocal bowel thickening with mucosal hyperenhancement, presence of skip areas, mesenteric vascular engorgement, with involvement of unusual sites like stomach, duodenum and rectum. These imaging findings in a child or young adult with appropriate clinical findings could suggest HSP.

Core tip: The gastrointestinal involvement in Henoch-Schonlein purpura produces typical imaging findings. In an appropriate clinical setting, these findings often suggest the diagnosis.

- Citation: Prathiba Rajalakshmi P, Srinivasan K. Gastrointestinal manifestations of Henoch-Schonlein purpura: A report of two cases. World J Radiol 2015; 7(3): 66-69

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1949-8470/full/v7/i3/66.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4329/wjr.v7.i3.66

Vasculitides are characterized by inflammation of walls of the blood vessels and their clinical manifestations depend on size and location of the involved vessels. Large vessel vasculitis (e.g., Takayasu arteritis) affects aorta and its largest branches and its gastrointestinal manifestations in the absence of systemic involvement are usually indistinguishable from mesenteric thromboembolic disease. Medium vessel vasculitis (e.g., polyarteritis nodosa) affects main visceral arteries and its branches and may lead to aneurysm formation with consequent gastrointestinal/intra-abdominal hemorrhage. Small vessel vasculitis involves arterioles, venules and capillaries and its bowel involvement is characterised by ulceration and stricture formation. Henoch-Schonlein purpura (HSP) is a type III hypersensitivity mediated small vessel vasculitis presenting with skin rashes, arthritis involving large joints, colicky abdominal pain, gastrointestinal hemorrhage and hematuria. In this article, we report two cases of gastrointestinal involvement of HSP and discuss its imaging features and radiological differential diagnoses.

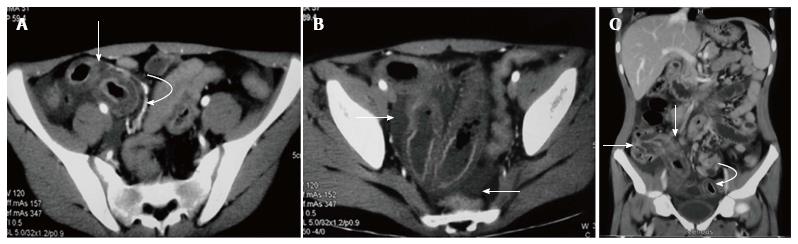

A 15-year-old male presented with history of skin rashes and joint pain for nearly a week. The skin rashes initially appeared in bilateral thighs which then progressed to bilateral hands and face. The patient also gave history of abdominal pain and melena. On clinical examination, the skin lesions were symmetrical, non-blanching and erythematous in nature. He was afebrile and his vitals were pulse rate 82/min and blood pressure 130/80 mmHg. Stool examination for occult blood was negative. Laboratory investigations were unremarkable (blood urea 43 mg%; serum creatinine 0.8 mg%; sodium 137 mg%; potassium 4.9 mg%). Computed tomography (CT) angiography of abdomen was performed which showed multifocal areas of symmetric small bowel wall thickening with intervening normal segments. Mural stratification was observed in the thickened bowel loops with enhancing mucosa/serosa and hypodense submucosa. The mesenteric vessels were engorged and mild free fluid was noted in pelvis. Biopsy from the skin lesions showed features of leukocytoclastic vasculitis. The diagnosis of HSP was made based on clinical features and biopsy findings. The patient was administered a short course of intravenous steroids followed by oral steroids. Abdominal symptoms resolved in a few days and the skin lesions disappeared by third week of initiation of treatment (Figure 1).

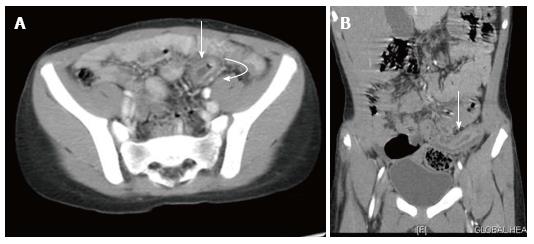

An 8-year-old male presented with 4 d history of skin rashes and 2 d history of severe abdominal pain. Skin rashes were erythematous in nature and were seen over bilateral gluteal regions. The child did not give any history of vomiting, altered bowel habits or melena. Laboratory investigations were unremarkable except for mild leucocytosis. Contrast enhanced CT of the abdomen was performed which showed long segment circumferential symmetric thickening of a mid-ileal loop with mural stratification. The adjacent mesenteric vessels were engorged and a few subcentimetric mesenteric lymph nodes were noted. Punch biopsy from skin lesions revealed granulocytes in vessel walls suggestive of leukocytoclastic vasculitis. The patient was treated with short course of oral steroids and supportive care. Abdominal pain subsided completely with initiation of steroids and skin lesions disappeared by second week (Figure 2).

HSP is an acute systemic small vessel vasculitis characterized by a classic palpable purpura, arthritis, gastrointestinal and renal manifestations[1]. It is the most common vasculitis of childhood and commonly occurs in children between 3 and 10 years of age; however it is known to affect young adults also. Many patients have a strong history of atopy and though the exact etiology is unknown, the disease is thought to result from an exaggerated immune response to a preceding, usually upper respiratory tract infection. There is consequent IgA and C3 containing immune complex deposition in small vessels of skin, joints, gastrointestinal tract and kidneys. Skin lesions are the earliest manifestation in majority of patients (approximately 70%) and typically develop in dependent locations like lower extremities and gluteal regions. These lesions start as erythematous papules which mature into purpura. Punch biopsy from skin lesions shows the presence of granulocytes in walls of small vessels which is termed as leukocytoclastic vasculitis. In about 75% of patients, transient arthritis involving large joints of lower limbs is seen[2].

Gastrointestinal involvement is seen in 50% to 75% patients and is often the most debilitating manifestation of HSP characterised by colicky abdominal pain, vomiting and gastrointestinal hemorrhage. Intramural hemorrhage and edema are the contributing factors to these symptoms. Gastrointestinal manifestations precede the appearance of skin lesions in 10%-15% patients and under such circumstances, differentiating from other numerous causes of acute abdomen is difficult[3,4]. On CT imaging, bowel involvement is seen as multifocal symmetric, circumferential wall thickening with target appearance. The target pattern is appreciable after administration of intravenous contrast and consists of enhancing mucosal and serosal layers due to hyperaemia with intervening hypodense submucosal layer due to edema. Associated findings include free intraperitoneal fluid, ileus of affected loop, vascular engorgement in the adjoining mesentery and non-specific lymphadenopathy[5].

The target sign is not specific for vasculitis and can be seen in many other conditions including ischemic bowel disease, idiopathic inflammatory bowel disease, infectious enterocolitis, radiation enteritis, etc. Common causes of mesenteric ischemia in children include cardioembolic occlusions, hypercoagulable states and venous obstruction secondary to midgut volvulus and incarcerated hernias. The imaging findings in early phase of mesenteric ischemia which is characterised by mucosal hyperaemia and edema are indistinguishable from those in HSP. CT angiography can be used to visualize the site of the arterial or venous occlusion; however a normal angiogram does not rule out the possibility of mesenteric ischemia[6]. The presence of skip lesions with intervening normal segments (as seen in Case 1), involvement of unusual sites like stomach, duodenum and rectum and bowel involvement not confining to a single vascular territory help in differentiating HSP from mesenteric ischemia[7]. Although the peak age of occurrence of crohn’s disease is second and third decades of life, approximately 25% cases occur in pediatric population (pediatric crohn). Wall thickening in active Crohn’s disease can be circumferential or eccentric involving the mesenteric border. Mesenteric vascular engorgement and skip areas are also seen in Crohn’s disease. However, terminal ileal involvement, fibrofatty proliferation, formation of stricture, sinus, fistula and abscess would favour Crohn’s disease over other conditions[8]. Infectious enteritis or colitis usually has mild wall thickening and less commonly, target appearance. Significant fat streakiness in the surrounding mesentery with presence of lymphadenopathy and ascites can point to infectious etiology; however correlation with laboratory investigations is essential for diagnosis.

Since the intramural hemorrhages are confined to mucosa and submucosa, HSP spontaneously resolves with conservative management in about 94% of children[9,10]. However in nearly 5% patients, there may be development of gastrointestinal complications including ileo-ileal intussusception, massive gastrointestinal hemorrhage, ileal perforation, stricture and protein losing enteropathy[11].

Renal involvement in HSP is seen in 40%-50% patients and in most cases occurs by first month. However, it may develop months to years after initial presentation and the manifestations may range in severity from asymptomatic hematuria to progressive glomerulonephritis. Other less frequent complications of HSP include pulmonary hemorrhage, myocardial infarction, orchitis, etc.

Uncomplicated HSP is usually managed with supportive care and steroids. Patients with renal involvement are treated with high dose pulsed steroids and immunosuppressive drugs to prevent progressive renal damage[2].

HSP generally has a self-limiting course; however recurrence has been reported in about 33% cases. Patients with renal involvement have a greater chance for disease recurrence and the long term outcome is determined predominantly by the severity of renal involvement[12].

To conclude, imaging findings in bowel involvement of HSP are typical and in the appropriate clinical setting, can corroborate to the diagnosis of HSP. Even when seen as an isolated manifestation, it can aid in narrowing down the possible differential diagnosis and in arriving at an early diagnosis.

The two young aged male patients presented with similar symptoms: skin rashes and abdominal pain.

In the first patient, erythematous skin rashes with melena and in the second patient, erythematous rashes with abdominal pain.

Ischemic bowel disease, idiopathic inflammatory bowel disease, infectious enterocolitis, radiation enteritis.

Case 1: Blood urea 43 mg%; serum creatinine 0.8 mg%; sodium 137 mg%; potassium 4.9 mg%; Case 2: Mild leukocytosis.

In both patients, computed tomography showed multifocal symmetric, circumferential wall thickening with target appearance and vascular engorgement in the adjoining mesentery.

Biopsy from skin lesions revealed granulocytes in vessel walls suggestive of leukocytoclastic vasculitis.

Both patients received steroids and supportive care.

The case report shows that imaging findings in Henoch-Schonlein purpura (HSP) are typical and in an appropriate clinical setting can suggest the diagnosis.

The authors present a very good review of a rather rare disease HSP. Both cases are very “academic”, and images provide a clear view of the diagnostic radiological findings.

P- Reviewer: Monclova JL S- Editor: Gong XM L- Editor: A E- Editor: Lu YJ

| 1. | Ha HK, Lee SH, Rha SE, Kim JH, Byun JY, Lim HK, Chung JW, Kim JG, Kim PN, Lee MG. Radiologic features of vasculitis involving the gastrointestinal tract. Radiographics. 2000;20:779-794. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 161] [Cited by in RCA: 117] [Article Influence: 4.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Sinclair P. Henoch-Schonlein purpura- a review. Curr Allergy Clin Immunol. 2010;23:116-120. |

| 3. | Mills JA, Michel BA, Bloch DA, Calabrese LH, Hunder GG, Arend WP, Edworthy SM, Fauci AS, Leavitt RY, Lie JT. The American College of Rheumatology 1990 criteria for the classification of Henoch-Schönlein purpura. Arthritis Rheum. 1990;33:1114-1121. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 562] [Cited by in RCA: 491] [Article Influence: 14.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Agha FP, Nostrant TT, Keren DF. Leucocytoclastic vasculitis (hypersensitivity angiitis) of the small bowel presenting with severe gastrointestinal hemorrhage. Am J Gastroenterol. 1986;81:195-198. [PubMed] |

| 5. | Jeong YK, Ha HK, Yoon CH, Gong G, Kim PN, Lee MG, Min YI, Auh YH. Gastrointestinal involvement in Henoch-Schönlein syndrome: CT findings. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1997;168:965-968. [PubMed] |

| 6. | Moschetta M, Telegrafo M, Rella L, Stabile Ianora AA, Angelelli G. Multi-detector CT features of acute intestinal ischemia and their prognostic correlations. World J Radiol. 2014;6:130-138. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 46] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Fernandes T, Oliveira MI, Castro R, Araújo B, Viamonte B, Cunha R. Bowel wall thickening at CT: simplifying the diagnosis. Insights Imaging. 2014;5:195-208. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 62] [Cited by in RCA: 83] [Article Influence: 7.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | d’Almeida M, Jose J, Oneto J, Restrepo R. Bowel wall thickening in children: CT findings. Radiographics. 2008;28:727-746. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Chung DJ, Park YS, Huh KC, Kim JH. Radiologic findings of gastrointestinal complications in an adult patient with Henoch-Schönlein purpura. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2006;187:W396-W398. [PubMed] |

| 10. | Sohagia AB, Gunturu SG, Tong TR, Hertan HI. Henoch-schonlein purpura-a case report and review of the literature. Gastroenterol Res Pract. 2010;2010:597648. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 42] [Cited by in RCA: 53] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Chen SY, Kong MS. Gastrointestinal manifestations and complications of Henoch-Schönlein purpura. Chang Gung Med J. 2004;27:175-181. [PubMed] |

| 12. | Tizard EJ, Hamilton-Ayres MJ. Henoch Schonlein purpura. Arch Dis Child Educ Pract Ed. 2008;93:1-8. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 64] [Cited by in RCA: 51] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |