Published online Nov 28, 2015. doi: 10.4329/wjr.v7.i11.415

Peer-review started: May 19, 2015

First decision: June 24, 2015

Revised: September 10, 2015

Accepted: October 12, 2015

Article in press: October 13, 2015

Published online: November 28, 2015

Processing time: 199 Days and 17.5 Hours

AIM: To evaluate the role of computed tomography (CT) for diagnosing traumatic injuries of the pancreas and guiding the therapeutic approach.

METHODS: CT exams of 6740 patients admitted to our Emergency Department between May 2005 and January 2013 for abdominal trauma were retrospectively evaluated. Patients were identified through a search of our electronic archive system by using such terms as “pancreatic injury”, “pancreatic contusion”, “pancreatic laceration”, “peri-pancreatic fluid”, “pancreatic active bleeding”. All CT examinations were performed before and after the intravenous injection of contrast material using a 16-slice multidetector row computed tomography scanner. The data sets were retrospectively analyzed by two radiologists in consensus searching for specific signs of pancreatic injury (parenchymal fracture and laceration, focal or diffuse pancreatic enlargement/edema, pancreatic hematoma, active bleeding, fluid between splenic vein and pancreas) and non-specific signs (inflammatory changes in peri-pancreatic fat and mesentery, fluid surrounding the superior mesenteric artery, thickening of the left anterior renal fascia, pancreatic ductal dilatation, acute pseudocyst formation/peri-pancreatic fluid collection, fluid in the anterior and posterior pararenal spaces, fluid in transverse mesocolon and lesser sac, hemorrhage into peri-pancreatic fat, mesocolon and mesentery, extraperitoneal fluid, intra-peritoneal fluid).

RESULTS: One hundred and thirty-six/Six thousand seven hundred and forty (2%) patients showed CT signs of pancreatic trauma. Eight/one hundred and thirty-six (6%) patients underwent surgical treatment and the pancreatic injures were confirmed in all cases. Only in 6/8 patients treated with surgical approach, pancreatic duct damage was suggested in the radiological reports and surgically confirmed in all cases. In 128/136 (94%) patients who underwent non-operative treatment CT images showed pancreatic edema in 97 patients, hematoma in 31 patients, fluid between splenic vein and pancreas in 113 patients. Non-specific CT signs of pancreatic injuries were represented by peri-pancreatic fat stranding and mesentery fluid in 89% of cases, thickening of the left anterior renal fascia in 65%, pancreatic ductal dilatation in 18%, acute pseudocyst/peri-pancreatic fluid collection in 57%, fluid in the pararenal spaces in 45%, fluid in transverse mesocolon and lesser sac in 29%, hemorrhage into peri-pancreatic fat, mesocolon and mesentery in 66%, extraperitoneal fluid in 66%, intra-peritoneal fluid in 41% cases.

CONCLUSION: CT represents an accurate tool for diagnosing pancreatic trauma, provides useful information to plan therapeutic approach with a detection rate of 75% for recognizing ductal lesions.

Core tip: Pancreatic trauma is associated with high morbidity and mortality especially in case of delayed diagnosis. Computed tomography (CT) represents an accurate imaging tool for recognizing direct and indirect signs of pancreatic trauma and provides useful information to plan therapeutic approach. Among the specific signs, the presence of fluid between the splenic vein and the pancreas represents the most common CT finding suggesting pancreatic injury and the potential of CT for detecting ductal lesions have improved as compared to previous studies, with a 75% detection rate.

- Citation: Moschetta M, Telegrafo M, Malagnino V, Mappa L, Ianora AAS, Dabbicco D, Margari A, Angelelli G. Pancreatic trauma: The role of computed tomography for guiding therapeutic approach. World J Radiol 2015; 7(11): 415-420

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1949-8470/full/v7/i11/415.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4329/wjr.v7.i11.415

Pancreatic trauma incidence ranges between 0.2% and 12% and occurs mainly in penetrating injuries with higher prevalence in children and young adults[1,2]. In case of blunt trauma, it is due to the impact of the organ against the adjacent vertebral column being the pancreatic body most commonly involved[3-5].

In 90% of cases, pancreatic lesions are associated with traumatic injuries of other abdominal organs as liver, spleen, stomach and duodenum[1,2].

Pancreatic trauma is associated with high morbidity and mortality especially in case of delayed diagnosis. In fact, the mortality ranges between 10% and 30% and is due to hemorrhagic lesions of the portal vein, splenic vein and inferior vena cava[1,6-20]. The reported morbidity rate is about 30% and mainly associated with pancreatic duct damage, consisting of fistulas, recurrent pancreatitis, pseudocysts, abscess, blood collections, retroperitoneal bleeding and ductal stenosis[6]. The diagnosis of early as late complications greatly increases the mortality rate which is mainly due to sepsis and multi-organ failure[6]. Clinical symptoms and signs of pancreatic injuries are nonspecific and include fever, leukocytosis, and elevated serum amylase or lipase levels.

Computed tomography (CT) represents the imaging technique of choice in hemodynamically stable patients with abdominal trauma, with reported sensitivity and specificity values as high as 80% in detecting pancreatic injuries being able to establish the type and grading of the detected lesions[8-14].

This study aims to evaluate the role of CT for diagnosing pancreatic injuries and guiding the choice of the therapeutic approach.

CT exams of 6740 patients admitted to our Emergency Department between May 2005 and January 2013 for abdominal trauma were retrospectively evaluated. Patients were identified through a search of our electronic archive system by using such terms as “pancreatic injury”, “pancreatic contusion”, “pancreatic laceration”, “peri-pancreatic fluid”, “pancreatic active bleeding”. The mean time between abdominal trauma and CT examination was about 1-2 h.

All patients were examined in an emergency setting. The CT scanner used was a 16-slice multidetector row CT (TSX - 101A - Aquilion 16, Toshiba Medical System, Tokyo, Japan). In all cases, scans were acquired before and after the intravenous injection of contrast material (120-140 mL injected at a rate of 3-3.5 mL/s), with image acquisition in the arterial phase, generally with a delay of 30-40 s from the beginning of contrast administration, in the portal venous phase, with a delay of 60-90 s from the beginning of contrast-agent administration and in delayed phase with a delay of 120-180 s from the beginning of contrast-agent administration[21].

The data sets were retrospectively analyzed on a workstation (HP XW 6400) equipped with image reconstruction software (Vitrea 4.0, Vital Images, Minneapolis, MN, United States). Multi-planar, Maximum Intensity Projection and Minimum Intensity Projection reconstructions were used.

Two radiologists in consensus assessed all images. Post-processing duration time was approximately 15 min.

CT images were evaluated searching for specific signs of pancreatic injury: parenchymal fracture; laceration; pancreatic edema; hematoma; active bleeding; and fluid between splenic vein and pancreas.

On the other side, non-specific signs were also assessed: peri-pancreatic fat or mesentery stranding; mesenteric fluid; thickening of the left anterior renal fascia; pancreatic ductal dilatation; acute peri-pancreatic fluid collection; fluid in the pararenal spaces; fluid in transverse mesocolon and lesser sac; hemorrhage into peri-pancreatic fat, mesocolon and mesentery; extraperitoneal fluid; and intra-peritoneal fluid[9,22]. Associated injuries to adjacent structures were also evaluated.

On the basis of CT findings, 136 out 6740 (2%) patients showed signs of traumatic injuries of the pancreas. In this group of patients, 90 patients were male and 46 were female with an average age of 45.4 ± 16.1 years (range: from 30 to 65 years old). Mechanism of injury was blunt motor vehicle collision in 70 patients, bicycle injury in 33, direct blow to the abdomen in 20, falls in 9 cases and sport related injury in 4 patients.

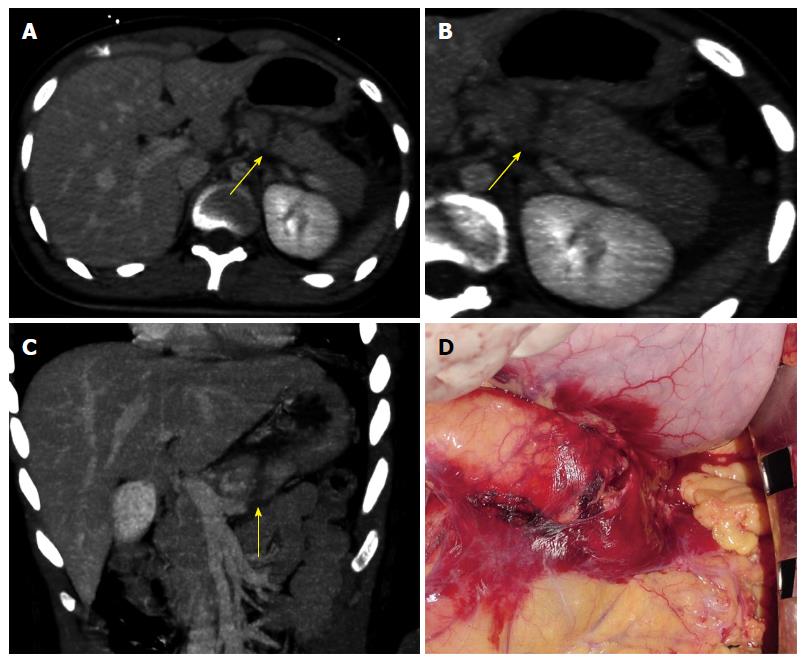

Eight out of 136 (6%) patients underwent surgical treatment within 8-12 h from the diagnosis and the pancreatic injures were confirmed in all cases, represented by 3 cases of parenchymal fracture (Figure 1) and 5 of extensive lacerations. Pancreatic injuries involved the conjunction between the neck and the body of the pancreas in 4 cases. Three patients had pancreatic body injuries and one had pancreatic tail injury. A complete pancreatic fracture line was identified on CT images in all patients and was identified as a linear discontinuity of the glandular parenchyma extending from the anterior to the posterior surface.

In all patients, fluid between splenic vein and pancreas was found.

In 6 out 8 patients treated with surgical approach, pancreatic duct damage was suggested in the radiological reports and surgically confirmed in all cases. In the remaining 2 patients, CT did not suggest a ductal injury but it was surgically detected.

One hundred and twenty-eight out of 136 (94%) patients underwent non-operative treatment and follow-up CT examination showed a resolution of the pathological findings. CT images showed pancreatic edema in 97 patients, hematoma in 31 patients, fluid between splenic vein and pancreas in 113 patients.

As regard with non-specific CT signs of pancreatic injuries, peri-pancreatic fat stranding and mesenteric fluid occurred in 122 out of 136 (89%) cases, thickening of the left anterior renal fascia in 88 out of 136 (65%), pancreatic ductal dilatation in 25 out of 136 (18%), acute pseudocyst/peri-pancreatic fluid collection in 78 out of 136 (57%), fluid in the pararenal spaces in 61 out of 136 (45%), fluid in transverse mesocolon and lesser sac in 40 out of 136 (29%), hemorrhage into peri-pancreatic fat, mesocolon and mesentery in 90 out of 136 (66%), extraperitoneal fluid in 90 out of 136 (66%), intra-peritoneal fluid in 56 out of 136 (41%) cases.

With regard to associated injuries to adjacent structures, in 27 out of 136 patients (20%) CT detected also extra-pancreatic findings represented by vertebral fracture (n = 11), liver contusion (n = 6), spleen contusion (n = 4), right kidney contusion (n = 3), small bowel injury (n = 2), left kidney contusion (n = 1).

CT represents the gold standard imaging technique for evaluating pancreatic trauma. Variable sensitivity and specificity values have been reported in the medical literature with an overall sensitivity in detecting all grades of pancreatic lesions of about 80%[9]. The specific CT findings of pancreatic injury are represented by parenchymal contusion, laceration, hematoma, active extravasation of contrast medium and fracture. Contusions are defined as areas of diminished density without discontinuity at the surface of the gland, lacerations as low-attenuation lines perpendicular to the long axis of the pancreas and fractures as clear separations of parenchymal fragments[9-11].

In our series specific CT signs of pancreatic trauma have been detected in all cases with the presence of fluid between the splenic vein and the pancreas being the most common and sensitive sign.

Lane et al[12] reported that fluid between the splenic vein and the pancreas allows to identify a pancreatic trauma and it is detected in 90% of cases of pancreatic injury.

This data is also confirmed in our series. In fact, fluid between the splenic vein and the pancreas occurred in all cases treated with surgical approach and in 88% of patients treated conservatively, with an overall rate of 89% in our series.

On the other side, peri-pancreatic fat stranding, peri-pancreatic fluid collections represent the most common indirect CT signs of pancreatic trauma occurring in the 89% of cases in our series[9-11].

The American Association for the Surgery of Trauma proposed a grading system mainly based on the site of pancreatic trauma and the integrity of the main pancreatic duct. In fact, a CT grading system has been established for supporting the surgical classification[9,12-15]. Therefore, CT allows to establish a grading of pancreatic injuries by providing important information for management of the gland lesions. Grade I lesions include minor contusions or lacerations with no duct injury (less than 50% of the thickness pancreatic), Grade II major contusions or lacerations with no duct injury, Grade III transections or major lacerations with duct disruption in distal pancreas, Grade IV transections of proximal pancreas or major lacerations with associated injury to the ampulla of Vater, Grade V massive disruption of the pancreatic head. The lesions involving the pancreatic head have a mortality rate almost double (28%) as compared to the tail injuries (16%), because of the inferior vena cava, inferior mesenteric vein and portal vein involvement[9,10,12-17].

Moreover, the most important prognostic factor is the destruction of the pancreatic duct which requires surgical or endoscopic treatment while the lesions which do not involve pancreatic duct can be treated by conservative treatment[16,17]. The rupture of the pancreatic duct is reported to be poorly detectable with CT, even if parenchymal laceration affecting more than 50% of the thickness of the gland are associated with high risk of pancreatic duct damage[18,19,23-25].

In fact, the main limitations of CT reported in the medical literature are represented by a low accuracy in detecting major ductal lesions which is reported to be about 43% and the underestimation of pancreatic injuries, especially in the first 12 h after the traumatic event. For this reason, a second CT examination is required within 24-48 h after admission in suspected pancreatic lesions in case of negative first CT[1,9,13].

In fact, in patients with suspected pancreatic duct lesion magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP) or endoscopic retrograde colangiopancreatography (ERCP) are strongly suggested. The MRCP represents the gold standard in this cases and it is reported to have diagnostic accuracy of 100% for evaluating to evaluate pancreatic duct damage[8]. However, ERCP allows direct imaging guided treatments. In fact, ERCP can guide surgical repair or can be used for stent placement. Many studies showed that mild pancreatic duct injuries may be treated with stent placement rather than surgical repair[19,20,23,24].

In our series, CT detected a ductal injury in 75% of cases. This value seems to be higher than the one reported in the literature; however, further studies in this field with a larger number of enrolled patients are required in order to confirm this data.

Our study presents some limitations represented by the limited number of patient with pancreatic injuries and the related impossibility to apply statistical tests to evaluate our data; the absence of repeated CT examinations in our series in case of negative first CT examination; the absence of MRI or ERCP evaluation in patient treated with conservative approach confirming pancreatic duct integrity; the lack of an inter-observer agreement evaluation; the retrospective type of the study and the lack of morbidity or mortality data in the current series.

In conclusion, CT represents an accurate imaging tool for recognizing direct and indirect signs of pancreatic trauma and provides useful information to plan therapeutic approach. Among the specific signs, the presence of fluid between the splenic vein and the pancreas represents the most common CT finding suggesting pancreatic injury and the potential of CT for detecting ductal lesions have improved as compared to previous studies, with a 75% detection rate.

Pancreatic trauma incidence ranges between 0.2% and 12% and is associated with high morbidity and mortality especially in case of delayed diagnosis. Computed tomography (CT) represents the imaging technique of choice in hemodynamically stable patients with abdominal trauma with reported sensitivity and specificity values as high as 80% in detecting pancreatic injuries being able to establish the type and grading of the detected lesions.

The increasing trend of non-operative management, especially in blunt trauma and stable patients, and the consequences of delayed or missed diagnosis makes CT the imaging modality of choice for evaluating pancreatic lesions.

CT represents an accurate imaging tool for recognizing direct and indirect signs of pancreatic trauma and provides useful information to plan therapeutic approach. The potential of CT for detecting ductal lesions have improved as compared to previous studies, with a 75% detection rate.

CT allows the radiologist to recognize all findings suggestive of severe pancreatic injury and also to detect the main alterations suitable for surgical approach. Therefore, a diagnostic and prognostic role can be given to this imaging tool.

This a very interesting study about the role of CT for diagnosis of pancreatic trauma, and as we know, pancreatic trauma is associated with high morbidity and mortality especially in case of delayed diagnosis. According to the result of this study, CT represents an accurate imaging tool for recognizing direct and indirect signs of pancreatic trauma, and provides useful information to plan therapeutic approach.

P- Reviewer: Chen F, Fu DL, Kozarek R, Sureka B S- Editor: Ji FF L- Editor: A E- Editor: Jiao XK

| 1. | Gupta A, Stuhlfaut JW, Fleming KW, Lucey BC, Soto JA. Blunt trauma of the pancreas and biliary tract: a multimodality imaging approach to diagnosis. Radiographics. 2004;24:1381-1395. [PubMed] |

| 2. | Holalkere NS, Soto J. Imaging of miscellaneous pancreatic pathology (trauma, transplant, infections, and deposition). Radiol Clin North Am. 2012;50:515-528. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Boffard KD, Brooks AJ. Pancreatic trauma--injuries to the pancreas and pancreatic duct. Eur J Surg. 2000;166:4-12. [PubMed] |

| 4. | Rekhi S, Anderson SW, Rhea JT, Soto JA. Imaging of blunt pancreatic trauma. Emerg Radiol. 2010;17:13-19. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 53] [Cited by in RCA: 57] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Madiba TE, Mokoena TR. Favourable prognosis after surgical drainage of gunshot, stab or blunt trauma of the pancreas. Br J Surg. 1995;82:1236-1239. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 40] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Bradley EL, Young PR, Chang MC, Allen JE, Baker CC, Meredith W, Reed L, Thomason M. Diagnosis and initial management of blunt pancreatic trauma: guidelines from a multiinstitutional review. Ann Surg. 1998;227:861-869. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 203] [Cited by in RCA: 218] [Article Influence: 8.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Dawson AR, Webster CH, Howe HC, Theron EJ, Meiring L. Rupture of the head of the pancreas by blunt trauma. A case report. S Afr Med J. 1985;67:560-562. [PubMed] |

| 8. | Wong YC, Wang LJ, Fang JF, Lin BC, Ng CJ, Chen RJ. Multidetector-row computed tomography (CT) of blunt pancreatic injuries: can contrast-enhanced multiphasic CT detect pancreatic duct injuries? J Trauma. 2008;64:666-672. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 38] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Venkatesh SK, Wan JM. CT of blunt pancreatic trauma: a pictorial essay. Eur J Radiol. 2008;67:311-320. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 50] [Cited by in RCA: 53] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Phelan HA, Velmahos GC, Jurkovich GJ, Friese RS, Minei JP, Menaker JA, Philp A, Evans HL, Gunn ML, Eastman AL. An evaluation of multidetector computed tomography in detecting pancreatic injury: results of a multicenter AAST study. J Trauma. 2009;66:641-646; discussion 646-647. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 53] [Cited by in RCA: 64] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Lee WJ, Foo NP, Lin HJ, Huang YC, Chen KT. The efficacy of four-slice helical CT in evaluating pancreatic trauma: a single institution experience. J Trauma Manag Outcomes. 2011;5:1. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Lane MJ, Mindelzun RE, Sandhu JS, McCormick VD, Jeffrey RB. CT diagnosis of blunt pancreatic trauma: importance of detecting fluid between the pancreas and the splenic vein. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1994;163:833-835. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 47] [Cited by in RCA: 50] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Teh SH, Sheppard BC, Mullins RJ, Schreiber MA, Mayberry JC. Diagnosis and management of blunt pancreatic ductal injury in the era of high-resolution computed axial tomography. Am J Surg. 2007;193:641-643; discussion 643. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 60] [Cited by in RCA: 47] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Lahiri R, Bhattacharya S. Pancreatic trauma. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 2013;95:241-245. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 41] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Brandon JC, Fields PA, Evankovich C, Wilson G, Teplick SK. Pancreatic clefts by penetrating vessels: a potential diagnostic for pancreatic fracture on CT. Emerg Radiol. 2000;7:283-286. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Degiannis E, Levy RD, Velmahos GC, Potokar T, Florizoone MG, Saadia R. Gunshot injuries of the head of the pancreas: conservative approach. World J Surg. 1996;20:68-71; discussion 72. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Lewis G, Krige JE, Bornman PC, Terblanche J. Traumatic pancreatic pseudocysts. Br J Surg. 1993;80:89-93. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 39] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Wong YC, Wang LJ, Lin BC, Chen CJ, Lim KE, Chen RJ. CT grading of blunt pancreatic injuries: prediction of ductal disruption and surgical correlation. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 1997;21:246-250. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 62] [Cited by in RCA: 67] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Linsenmaier U, Wirth S, Reiser M, Körner M. Diagnosis and classification of pancreatic and duodenal injuries in emergency radiology. Radiographics. 2008;28:1591-1602. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 92] [Cited by in RCA: 97] [Article Influence: 5.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Yang L, Zhang XM, Xu XX, Tang W, Xiao B, Zeng NL. MR imaging for blunt pancreatic injury. Eur J Radiol. 2010;75:e97-101. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Moschetta M, Stabile Ianora AA, Pedote P, Scardapane A, Angelelli G. Prognostic value of multidetector computed tomography in bowel infarction. Radiol Med. 2009;114:780-791. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Daly KP, Ho CP, Persson DL, Gay SB. Traumatic Retroperitoneal Injuries: Review of Multidetector CT Findings. Radiographics. 2008;28:1571-1590. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 63] [Cited by in RCA: 49] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Soto JA, Alvarez O, Múnera F, Yepes NL, Sepúlveda ME, Pérez JM. Traumatic disruption of the pancreatic duct: diagnosis with MR pancreatography. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2001;176:175-178. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 93] [Cited by in RCA: 98] [Article Influence: 4.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Chinnery GE, Krige JE, Kotze UK, Navsaria P, Nicol A. Surgical management and outcome of civilian gunshot injuries to the pancreas. Br J Surg. 2012;99 Suppl 1:140-148. [PubMed] |

| 25. | Körner M, Krötz MM, Degenhart C, Pfeifer KJ, Reiser MF, Linsenmaier U. Current Role of Emergency US in Patients with Major Trauma. Radiographics. 2008;28:225-242. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 125] [Cited by in RCA: 103] [Article Influence: 6.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |