Published online Aug 28, 2014. doi: 10.4329/wjr.v6.i8.613

Revised: April 15, 2014

Accepted: July 18, 2014

Published online: August 28, 2014

Processing time: 197 Days and 19.5 Hours

Like other parts of the gastrointestinal tract (GIT), duodenum is subject to a variety of lesions both congenital and acquired. However, unlike other parts of the GIT viz. esophagus, rest of the small intestine and large intestine, barium evaluation of duodenal lesions is technically more challenging and hence not frequently reported. With significant advances in computed tomography technology, a thorough evaluation including intraluminal, mural and extramural is feasible in a single non-invasive examination. Notwithstanding, barium evaluation still remains the initial and sometimes the only imaging study in several parts of the world. Hence, a thorough acquaintance with the morphology of various duodenal lesions on upper gastrointestinal barium examination is essential in guiding further evaluation. We reviewed our experience with various common and uncommon barium findings in duodenal abnormalities.

Core tip: Barium evaluation of duodenal pathologies is technically more challenging than rest of gastrointestinal tract. Barium study still forms an initial and integral part of evaluation as it provide useful clues to the diagnosis and guide further evaluation. This article should alert the radiologist to consider various common and uncommon duodenal pathologies in the correct clinical setting to guide the clinician for further investigations to ensure correct diagnosis and enable appropriate treatment.

- Citation: Gupta P, Debi U, Sinha SK, Prasad KK. Upper gastrointestinal barium evaluation of duodenal pathology: A pictorial review. World J Radiol 2014; 6(8): 613-618

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1949-8470/full/v6/i8/613.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4329/wjr.v6.i8.613

Duodenum is often an overlooked segment of the gastrointestinal tract (GIT) as much of the GIT Radiology literature has focused on the esophagus, stomach, distal small bowel and colon. Duodenum like other parts of the GIT is affected by a variety of pathologic conditions including congenital, inflammatory and neoplastic diseases. While some of the congenital abnormities like duplications and diverticulae are usually asymptomatic, others like annular pancreas and malrotation may manifest in the first decade of life. Inflammatory involvement of the duodenum results from peptic ulcer disease, Crohn’s disease (CD) and adjacent inflammatory conditions. Duodenal neoplasms are rare and malignant tumors are much more common than benign tumors. Although, there are no specific signs of the various duodenal pathologies on upper GIT barium series, barium evaluation still forms an integral part of evaluation of patients in several parts of the world due to easy availability and relatively less cost. However, computed tomography (CT) and endoscopy have a greater sensitivity and specificity in detecting duodenal pathologies. CT, in particular provides information about both intramural and extramural disease processes. When used as an initial imaging tool, barium examination does provide useful clues to the underlying pathophysiological processes and as such guide the choice of further tests. Barium examination of duodenum may be contraindicated in suspected leak, history of recent surgery or acute trauma. In these situations, water soluble contrast study replaces barium study. Correct diagnosis requires a thorough knowledge of the appearance of disease processes of duodenum on barium studies. We present a brief barium pictorial review of common and uncommon duodenal lesions.

Except for the bulb, duodenum is a retroperitoneal structure. It lies within the anterior pararenal space. Forming a C-loop segment around the pancreatic head, this 30 cm tube extends from pylorus to the ligament of Treitz. It is arbitrarily divided into four parts based on their anatomic orientation. The relationship of the proximal and distal end to the spine is important. The pyloric end of the duodenum lies to the right of the spine and the duodenojejunal (DJ) flexure to the left of the pedicle of the spine.

The embryological basis is inadequate rotation of the intestinal loop around the axis of the superior mesenteric artery (SMA) during fetal life, around 10th week of development. Malrotation may occur as an isolated congenital anomaly or as a part of visceral situs anomalies[1]. In practical terms, malrotation can be classified into three types: non-rotation, malrotation and reverse rotation[2]. Former, the most common type is usually asymptomatic and incidentally detected and is imprecisely labeled as non-rotation. Reverse rotation is rare.

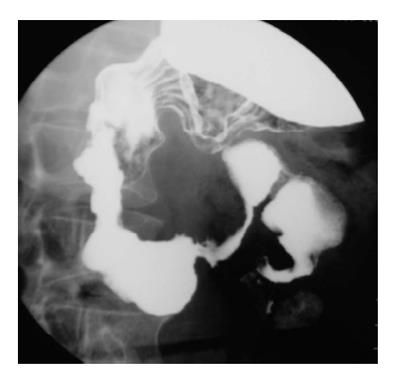

Upper gastrointestinal (UGI) barium study is accurate for detection of malrotation. The DJ junction does not cross the midline and is below the duodenal bulb (Figure 1). Delayed evaluation usually shows abnormal location of the right colon. Though abnormal position of caecum is suggestive, normal position does not exclude the diagnosis as it can be normally location in 20% cases[3].

Most common site for duplication in the GIT is ileocecal region. Duodenal duplication is relatively uncommon congenital anomaly, accounting for less than 10% of all GIT duplications[4]. It is typically located along the mesenteric aspect of the first and second parts of the duodenum. On barium evaluation, extrinsic mass effect is noted on the duodenum and greater curvature of the stomach (Figure 2). Though rare, communication with the duodenum can be found. The barium findings are non-specific. Differential diagnosis include choledochal cyst, pancreatic lesions including pancreatic masses, pseudocyst, etc. and large duodenal diverticulum. A specific diagnosis can be made on high resolution ultrasonography if classical multi-layered appearance (gut signature) is seen[5].

Duodenal diverticulum can be congenital or acquired. It is a frequent incidental finding detected in about 5% of upper GIT barium studies[6]. The most common site is along mesenteric border of second part of duodenum near the ampulla of Vater. It is seen as barium filled out pouching along the medial aspect of the second part of duodenum, although other locations are not uncommon (Figure 3).

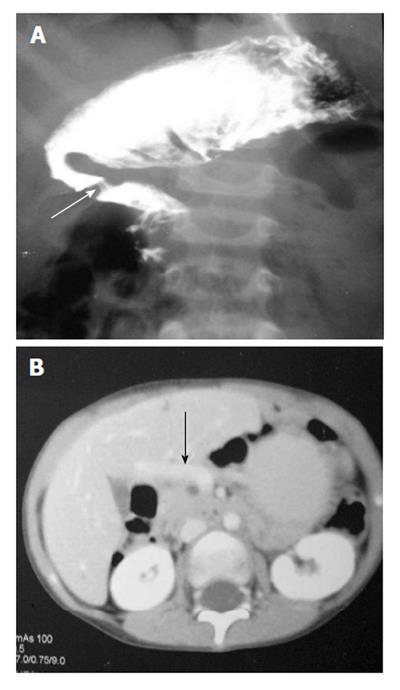

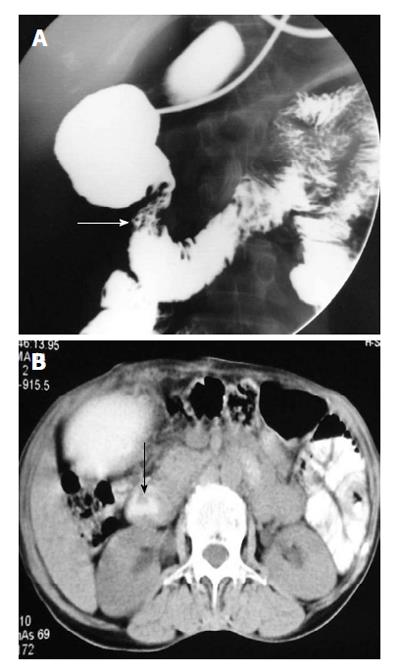

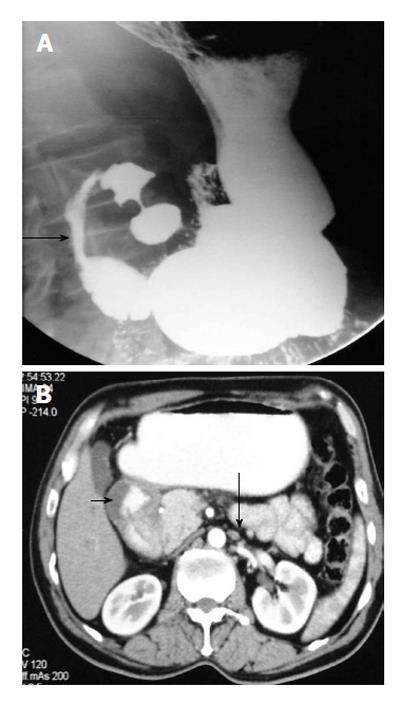

It usually occurs in association with other congenital malformation, most commonly malrotation, pancreatic, splenic and cardiac anomalies. The portal vein passes anterior to the duodenum and pancreatic head[7]. On barium study, it appears as an extrinsic linear impression on the proximal duodenum or obstruction of the proximal duodenum (Figure 4A). The correct diagnosis is made by contrast enhanced CT that shows the abnormal location of portal vein (Figure 4B).

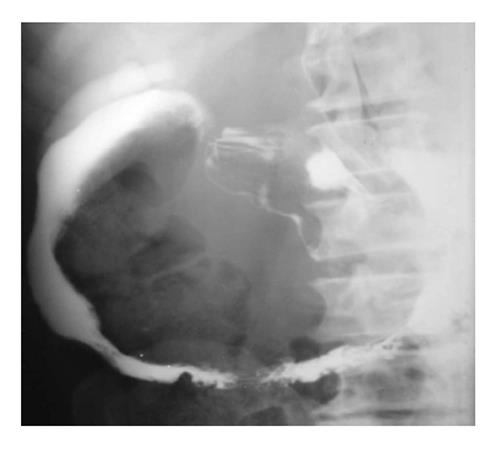

The embryologic basis of the annular pancreas is a defect in the normal rotation of the ventral pancreatic anlage. The result of this aberration is encircling of the second part of duodenum by pancreatic tissue. The annulus encircles the duodenum partially or completely[8]. Pathologically, it is usually loosely applied to the serosa of the duodenum. In extreme cases, the pancreatic tissue is interdigitated with the wall of the duodenum. On barium study, it produces a smooth or tapered narrowing of the second part of the duodenum (Figure 5A). The diagnosis is confirmed by cross-sectional imaging, usually a CT scan (Figure 5B).

There are several varieties of webs: complete duodenal atresias (imperforate webs), wind sock webs and webs with central or eccentric apertures. The most common sites of web are in vicinity of the ampulla either preampullary or postampullary location[8] (Figure 6). Upper GIT barium study shows the abnormality as a short segment transverse filling defect in the descending duodenum.

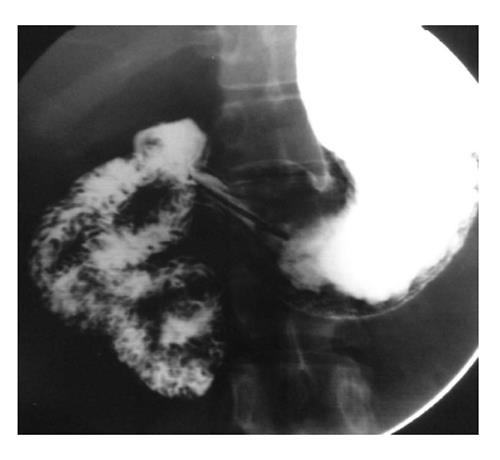

Brunner’s gland hyperplasia is a frequent asymptomatic finding on upper GIT barium evaluation. It is seen as solitary or multiple nodular filling defects that are typically less than 5 mm in diameter in the proximal duodenum[9]. When extensive, the nodules lead to a cobblestone or Swiss-cheese pattern (Figure 7). The differential diagnoses for such filling defects in the duodenum include heterotopia, nodular lymphoid hyperplasia, multiple adenomas in familial adenomatous polyposis, hamartomas in Peutz-Jeghers syndrome, carcinoid tumors and metastatic deposits.

Peptic ulcer disease: Duodenal ulcers (DUs) are common and affect nearly one-tenth of the adult population. DUs are almost always benign. This is unlike gastric ulcers where 5% of the ulcers can be malignant. Though endoscopy is the most sensitive and specific method for diagnosis of suspected DUs, it is invasive and costly. Double-contrast UGI barium study still remains a useful alternative to endoscopy[10]. More than 90% of DUs occur in the duodenal bulb and nearly 50% of these occur on the anterior wall. Ulcer craters are seen as well-defined round or ovoid pools of barium, surrounded by a symmetrical mound of edematous mucosa. Adjacent radiating mucosal folds converge to the edge of the crater. Healed ulcer leads to deformity of the bulb (Figure 8A). The uncommon variety of DUs, postbulbar ulcers are usually located along the medial aspect of the second part of duodenum above the ampulla of Vater (Figure 8B). Diagnosis on barium study is hampered by location; however indentation of the lateral wall of the duodenum opposite the ulcer due to spasm offers a clue[10].

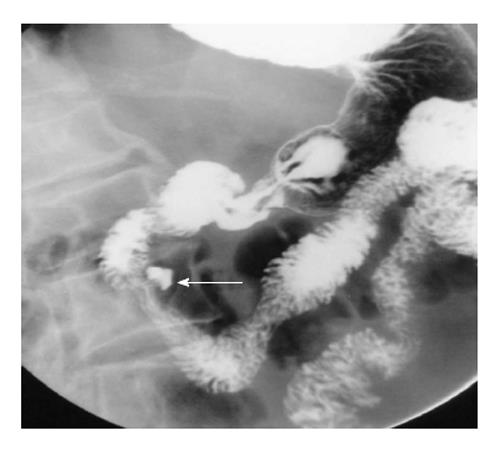

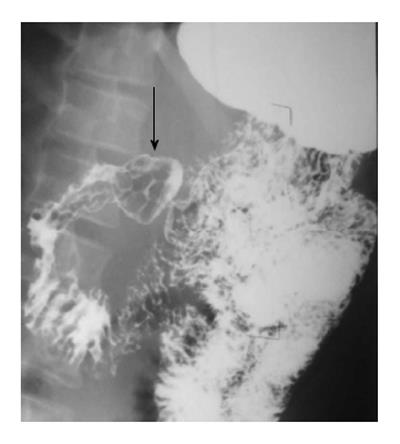

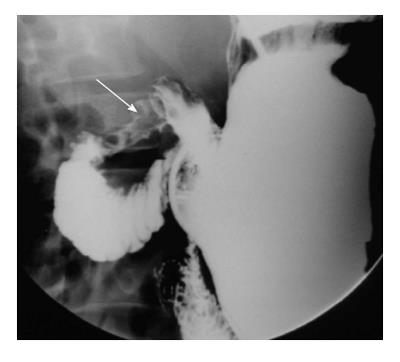

Tuberculosis: Duodenal tuberculosis (TB) comprises 2% of gastrointestinal TB. Clinically, the patients are divided into two groups: those having dyspeptic symptoms and those with obstructive symptoms. In the former group, barium findings include: luminal narrowing, ulcerations and extrinsic compression. These changes typically spare the proximal duodenum. Less frequently, scarring of duodenal cap, widening of the C-loop are noted. In the group with obstructive symptoms, findings include luminal narrowing of varying degrees (Figure 9) or cut off at junction of second and third part of duodenum resembling the SMA syndrome.

Concomitant tuberculous involvement of rest of the GIT is fairly common. Associated involvement of biliary tract can be noted (Figure 9). This takes the form of air in the common bile duct or reflux of barium into the biliary tree.

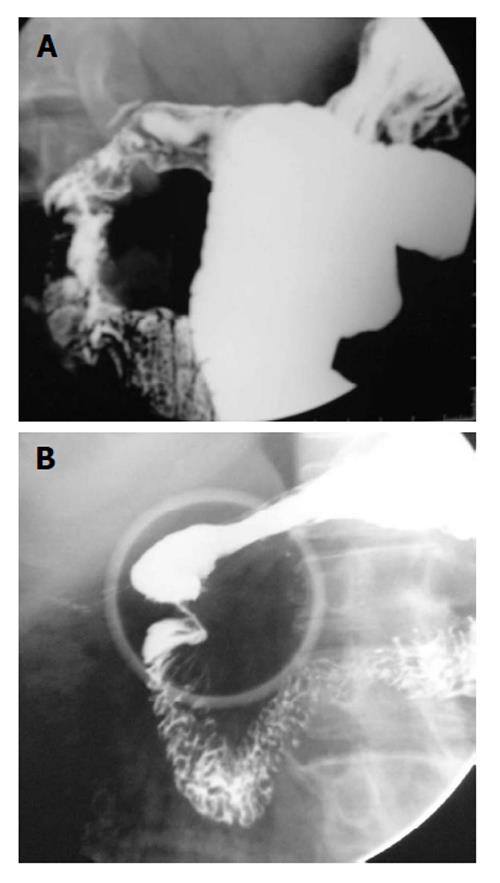

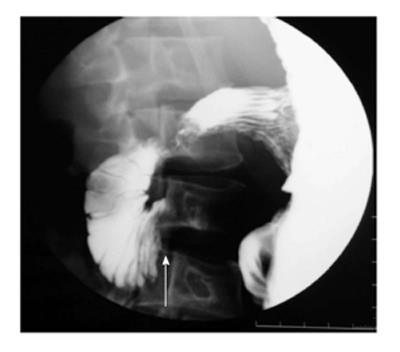

CD: CD affects the upper GIT mucosa in 20%-40% of patients. Early disease leads to irregular thickening, edema and cobblestone appearance. With disease progression, there is fibrosis and stenosis of the involved segment. Finally a string sign may develop. There are three patterns of involvement in advanced disease. The first and the most common pattern is the contiguous involvement of stomach and duodenum[11]. Other two patterns are isolated involvement of proximal and distal duodenum (Figure 10). Less common findings are development of fissures, pseudodiverticulae and reflux of contrast into the biliary tree. Advanced gastroduodenal involvement may lead to pseudo-Billroth I appearance.

Extrinsic inflammatory or neoplastic diseases affecting the duodenum: Nonspecific duodenal wall thickening may occur in inflammatory conditions of pancreas or gall bladder. In addition, adjacent neoplastic processes can involve duodenum, e.g., pancreatic adenocarcinoma.

Duodenal dystrophy: This entity is associated with groove pancreatitis, a variant of chronic pancreatitis. It is characterised by the presence of multiple cystic lesions in the duodenal wall that is thickened because of chronic inflammation[12]. Barium findings are non-specific and demonstrate only stenosis of the involvement segment with or without irregularity of outline (Figure 11). Endoscopic ultrasound is the modality of choice. CT shows thickened duodenal wall between the duodenal lumen and pancreas. Cystic lesions are noted within the thickened wall.

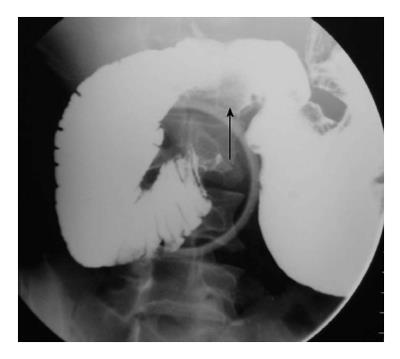

SMA syndrome is a rare condition characterised by acute angulation of SMA leading to compression of the third part of the duodenum between the SMA and the aorta[13]. The basic etiological factor is loss of abdominal fat due to a variety of debilitating conditions. Upper GIT barium study shows extrinsic compression of the third part, dilatation of the proximal duodenum and a collapsed small bowel distal to the impression of SMA (Figure 12).

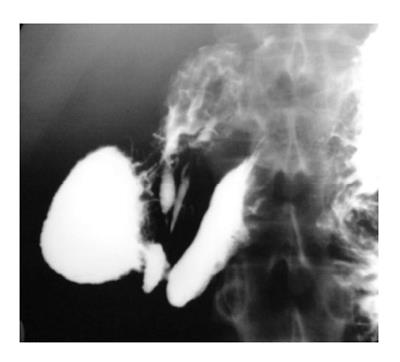

Duodenal tumors account for about one-third of small bowel neoplasm. Overall small bowel tumors comprise only 5% of the gastrointestinal tumors. Benign tumors are rare. These include adenomatous polyp, lipoma and leiomyoma. Primary adenocarcinoma is the most common malignant lesion of the duodenum and is usually found in the periampullary region[14] (Figure 13). It presents as either a polypoidal mass causing filling defect or an irregular, annular constricting lesion with deformity of the lumen and mucosal irregularity. Rare malignant lesions include lymphoma (Figure 14) and malignant gastrointestinal stromal tumors.

Duodenal pathologies are distinct from those in rest of the GIT. Upper gastrointestinal barium study comprises one of the initial methods of evaluation of duodenal pathologies. Though, not entirely specific for a particular pathological entity, barium studies do provide a fairly good idea about the underlying disease pattern and guide further management.

P- Reviewer: El-Sayed M, Li YY, Maglinte DDT, Perju-Dumbrava D, Slomiany BL S- Editor: Wen LL L- Editor: A E- Editor: Liu SQ

| 1. | Snyder WH, Chaffin L. Embryology and pathology of the intestinal tract: presentation of 40 cases of malrotation. Ann Surg. 1954;140:368-379. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 144] [Cited by in RCA: 110] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Maxson RT, Franklin PA, Wagner CW. Malrotation in the older child: surgical management, treatment, and outcome. Am Surg. 1995;61:135-138. [PubMed] |

| 3. | Berdon WE. The diagnosis of malrotation and volvulus in the older child and adult: a trap for radiologists. Pediatr Radiol. 1995;25:101-103. [PubMed] |

| 4. | Macpherson RI. Gastrointestinal tract duplications: clinical, pathologic, etiologic, and radiologic considerations. Radiographics. 1993;13:1063-1080. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 316] [Cited by in RCA: 284] [Article Influence: 8.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Fidler JL, Saigh JA, Thompson JS, Habbe TG. Demonstration of intraluminal duodenal diverticulum by computed tomography. Abdom Imaging. 1998;23:38-39. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Stone EE, Brant WE, Smith GB. Computed tomography of duodenal diverticula. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 1989;13:61-63. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Talus H, Roohipur R, Depaz H, Adu AK. Preduodenal portal vein causing duodenal obstruction in an adult. J Am Coll Surg. 2006;202:552-553. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Hwang JI, Chiang JH, Yu C, Cheng HC, Chang CY, Mueller PR. Pictorial review: Radiological diagnosis of duodenal abnormalities. Clin Radiol. 1998;53:323-332. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Gore RM, Levine MS. Textbook of gastrointestinal radiology. 2nd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Saunders 2000; 593-595. |

| 10. | Levine MS, Creteur V, Kressel HY, Laufer I, Herlinger H. Benign gastric ulcers: diagnosis and follow-up with double-contrast radiography. Radiology. 1987;164:9-13. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 44] [Cited by in RCA: 43] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Nugent FW, Richmond M, Park SK. Crohn’s disease of the duodenum. Gut. 1977;18:115-120. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 97] [Cited by in RCA: 94] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Procacci C, Graziani R, Zamboni G, Cavallini G, Pederzoli P, Guarise A, Bogina G, Biasiutti C, Carbognin G, Bergamo-Andreis IA. Cystic dystrophy of the duodenal wall: radiologic findings. Radiology. 1997;205:741-747. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 73] [Cited by in RCA: 51] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Lippl F, Hannig C, Weiss W, Allescher HD, Classen M, Kurjak M. Superior mesenteric artery syndrome: diagnosis and treatment from the gastroenterologist’s view. J Gastroenterol. 2002;37:640-643. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 86] [Cited by in RCA: 93] [Article Influence: 4.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Kazerooni EA, Quint LE, Francis IR. Duodenal neoplasms: predictive value of CT for determining malignancy and tumor resectability. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1992;159:303-309. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 53] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |