Revised: December 23, 2013

Accepted: January 13, 2014

Published online: February 28, 2014

Processing time: 135 Days and 11 Hours

Transomental hernias are among the rarest type of all internal hernias which overall account for less than 6% of small bowel obstructions. Most transomental hernias occurring in adults are either iatrogenic or post-traumatic. More rarely, a spontaneous herniation of small bowel loops may result from senile atrophy of the omentum. We report a case of an 86-year-old male who presented with signs and symptoms of small bowel obstruction but had no past surgical or traumatic abdominal history. At contrast-enhanced multi-detector row computed tomography (CT), a cluster of fluid-filled dilated small bowel loops could be appreciated in the left flank, with associated signs of bowel wall ischemia. Swirling of the mesenteric vessels could also be appreciated and CT findings were prospectively considered consistent with a strangulated small bowel volvulus. At laparotomy, no derotation had to be performed but up to 100 cm of gangrenous small bowel loops had to be resected because of a transomental hernia through a small defect in the left part of the greater omentum. Retrospective reading of CT images was performed and findings suggestive of transomental herniation could then be appreciated.

Core tip: Transomental hernias are among the rarest type (1%) of all internal hernias, often being either iatrogenic or post-traumatic. More rarely, a spontaneous herniation may occur. We report a case of an 86-year-old male with a small bowel obstruction and no past surgical or traumatic abdominal history. Contrast-enhanced multi-detector row computed tomography showed findings consistent with a strangulated small bowel volvulus. At laparotomy, however, no derotation had to be performed but up to 100 cm of gangrenous small bowel loops had to be resected because of a strangulated transomental hernia which was prospectively overlooked but could then be retrospectively appreciated.

- Citation: Camera L, Gennaro AD, Longobardi M, Masone S, Calabrese E, Vecchio WD, Persico G, Salvatore M. A spontaneous strangulated transomental hernia: Prospective and retrospective multi-detector computed tomography findings. World J Radiol 2014; 6(2): 26-30

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1949-8470/full/v6/i2/26.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4329/wjr.v6.i2.26

Internal hernias, defined as the protrusion of a viscus through a normal or an abnormal aperture within the peritoneal cavity, are relatively uncommon clinical conditions, accounting for only up to 5.8% of small bowel obstructions, with an overall incidence of 0.5%-0.9%[1].

Indeed, most internal hernias involve small bowel loops and occur through either congenital or acquired defects of attachment of various peritoneal folds, with the paraduodenal (53%) and pericecal (13%) hernias being the most common, followed by the hernias through the foramen of Winslow (8%), the transmesenteric (2%) and the transomental hernias (1%)[2].

These latter are the rarest type of internal hernias and, while possibly being congenital in a minority of cases of pediatric age[3], they are most often iatrogenic. Indeed, most transomental hernias occur as a result of previous abdominal surgery, mostly after Roux-en-Y gastric bypass[4]. However, senile atrophy of the omentum may lead to a this rare type of internal hernia, even in patients without a past surgical history[5].

Herein, we report a case of an 86-year-old male patient with contrast-enhanced multi-detector computed tomography (CT) findings consistent with a strangulated small bowel volvulus who was found to have a spontaneous transomental hernia at surgery.

An 86-year-old male patient was admitted to the surgical department of our institution with an acute abdomen. The patient reported sudden onset of abdominal pain and vomiting, along with nausea and sweating. The patient’s medical history revealed chronic constipation with no prior surgical procedures, blunt abdominal traumas or inflammatory bowel diseases. Vital parameters were all within normal limits except for a pulse rate of 80 beats/min. At physical examination, a marked abdominal distension could be appreciated with signs of peritonism in the left flank. Laboratory findings were unremarkable except for a mild anemia (3.9 × 106/mL; n.v. 4.2-5.6 × 106 mL) and a mild leukocytosis (12.53 × 103/mL with 88.6% neutrophils).

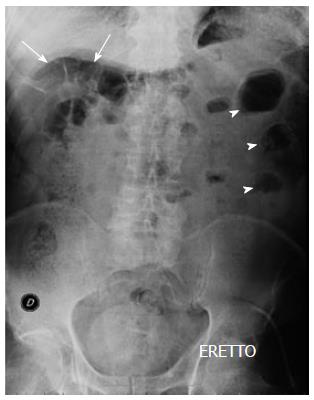

An upright abdominal plain film (Figure 1) showed small bowel air-fluid levels in the left flank with air-driven distension of small bowel loops in the right hypochondrium and paucity of gas in the pelvis.

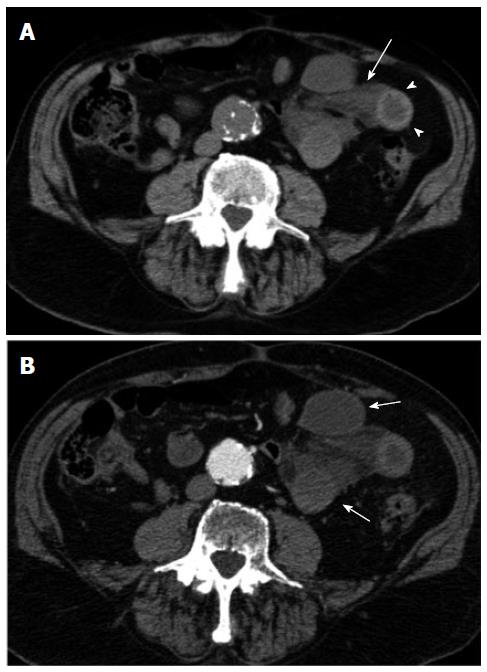

The patient underwent both unenhanced and contrast-enhanced multi-detector row CT (Aquilion 64, Toshiba, Japan) with a detector configuration of 1 mm × 32 mm, a table feed of 36 mm/s and a gantry rotation time of 0.75 (pitch factor = 0.844), 5 mm slice thickness, 120 kVp and automatic dose modulation. Unenhanced scans showed a cluster of fluid-filled jejunal loops, one of which with a thickened hemorrhagic wall in the left flank. Mesenteric fluid was also evident (Figure 2A).

A monophasic contrast-enhanced acquisition performed with a fixed scan delay of 70 s after i.v. bolus injection of 150 cc of non ionic iodinated contrast media (Ultravist 370; Bayer-Shering Pharma, Berlin, Germany) at a rate of 2 cc/s. resulted in an early arterial phase imaging because of a significant delay in the transit time of the patient (Figure 2B).

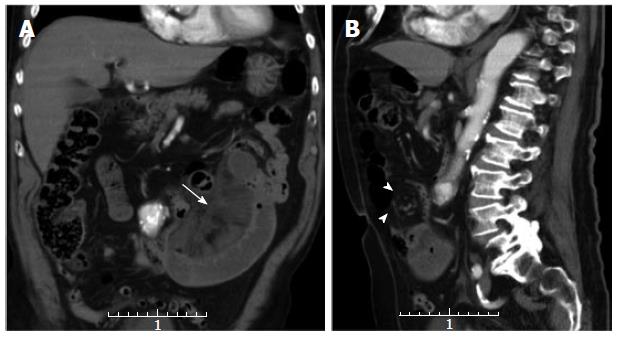

However, contrast-enhanced CT scans confirmed the presence of a strangulated small bowel occlusion with lack of enhancement of the bowel wall, best depicted on the coronal reformatted image (Figure 3A) and swirling (whirl sign) of the mesenteric vessels (Figure 3B). CT findings were thus considered consistent with a strangulated small bowel volvulus.

The patient underwent immediate surgery. At laparotomy, however, no derotation had to be performed but up to 100 cm of gangrenous jejunal loops had to be resected because of a strangulated transomental hernia through a small defect in the left part of the greater omentum. Post-operative course was almost uneventful and the patient was discharged 14 d after surgery.

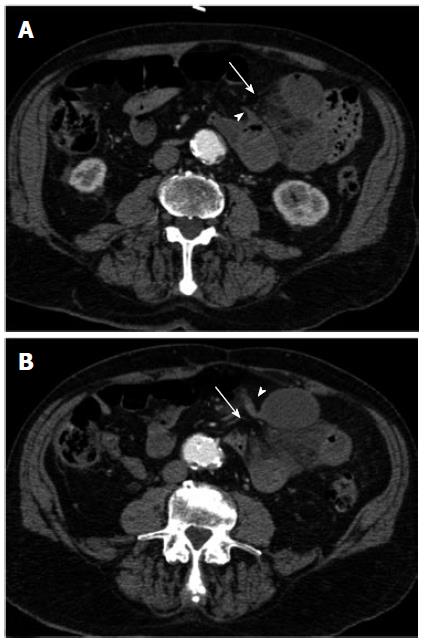

Retrospective reading of CT scans was performed and a number of CT signs suggestive of transomental hernia could then be appreciated (Figure 4).

Internal hernias are among the rarest cause of small bowel obstruction, with an overall incidence of 0.5%-0.9%[1]. Transomental hernias, in particular, account for only 1% of all internal hernias and have a bimodal age distribution, occurring in both pediatric and adult patients[2]. Transomental hernias in the pediatric age occur through congenital defects in either the greater omentum or the gastrocolic ligament[3]. In such instances, the herniated bowel may spontaneously reduce or become incarcerated depending on the size of the orifice and the length of herniated loops[6]. In adulthood, however, transomental herniation of small bowel loops is more commonly iatrogenic, mostly resulting from Roux-en-Y anastomosis in gastric bypass surgery[4]. Less commonly, transomental hernias in adults can result from either blunt abdominal trauma or peritoneal inflammation[2]. More rarely, transomental hernias may occur as a result of senile atrophy of the greater omentum in patients without any surgical, traumatic or inflammatory history. This type of transomental hernia is indeed referred to as a spontaneous transomental hernia[5].

As the clinical picture of internal hernias is not specific, pre-operative diagnosis is difficult and this often results in a delayed surgical management when intestinal necrosis has occurred[1]. This is particularly true for transomental hernias which lack a hernial sac and usually occur through very narrow defects[2]. Such was the case of our patient who presented with signs of peritonism in the left flank at admission.

In the clinical setting of small bowel obstruction, diagnosis of an internal hernia often relies on CT findings which, however, are seldom specific[1,2,7]. Indeed, only four (16%) out of 25 CT scans were considered suspicious for internal hernia in the series of Ghiassi et al[1]. In our case, CT findings were wrongly considered consistent with a strangulated small bowel volvulus. This diagnostic impression was largely based on the swirling of the mesenteric vessels (whirl sign) which was best depicted on the sagittal reformatted image (Figure 3B). However, while this CT sign has shown a positive predictive value of 80% for surgery in the setting of small bowel obstruction[8], its reliability for the diagnosis of small bowel volvulus has been questioned[9]. Indeed, in our case it proved to be a false positive finding.

However, internal hernias can be either mistaken for or complicated by a small bowel volvulus[2,7] and this is especially true for those without an hernial sac, such as both transmesenteric and transomental hernias[10]. At CT, differential diagnosis between an internal hernia and a small bowel volvulus is difficult, albeit crucial, as the former is more often associated with gangrene at laparotomy[2,7,10]. The presence of multiple transition points as well as their location relative to the lumbar spine are useful predictors of volvulus along with the whirl sign[11], whereas the peripheral location within the peritoneal cavity and the mere stretching and engorgement of the mesenteric vessels suggest a transmesenteric or a transomental hernia[2,7,10].

As far as the CT diagnosis of a strangulated small bowel obstruction is concerned, all established CT criteria of bowel wall ischemia could be appreciated, such as the presence of mesenteric fluid and the lack of enhancement of the bowel wall[12-14]. This latter CT finding has been acknowledged as the most specific sign of bowel wall ischemia[13]. In our case, up to 100 cm of gangrenous small bowel had to be resected.

As far as the mural hematoma (Figure 2A) is concerned, while it can also result from non obstructing causes such as blunt abdominal trauma or anti-coagulant therapy[15], it can be confidently considered an additional CT sign of bowel wall ischemia whenever it is observed in the setting of small bowel obstruction and it is associated with bowel wall thickening[15].

While the presence of a cluster of fluid-filled small bowel loops is highly predictive for the CT diagnosis of internal hernia[2,7,10] and the peripheral location of the herniated loops within the peritoneal cavity are quite characteristic features of transomental hernias[16], these findings are subtle and could only be retrospectively appreciated along with the beak-like appearance of the closely apposed afferent and efferent loops and the hernial orifice in the left part of the omentum (Figure 4). However, even on retrospective analysis of CT image displacement of any other bowel segments, an additional typical feature of transomental hernia[16] could not be observed. Moreover, while most transomental hernias occur on the right side of the greater omentum[16], in our case a cluster of fluid-filled loops was observed in the left flank (Figures 2-4).

We have herein reported multi-detector row CT findings in a rare case of a left-sided spontaneous strangulated transomental hernia.

An 86-year-old male with acute abdominal pain and vomiting.

Acute abdomen with signs of peritonism in the left flank.

Differential diagnosis between internal hernias and small bowel volvulus is difficult, albeit crucial, because the former is more often associated with necrosis at laparotomy.

Red blood cell: 3.9 × 106/mL; white blood cell: 12.53 × 103/mL. Other laboratory tests were within normal limits.

Contrast-enhanced multi-detector computed tomography (CT) findings were consistent with a strangulated small bowel volvulus showing a cluster of fluid-filled dilated loops with associated mesenteric edema and fluid.

At laparotomy, no derotation was performed but up to 100 cm of gangrenous jejunal loops had to be resected because of a strangulated transomental hernia through a small defect in the left part of the greater omentum.

Transomental hernias are among the rarest type of internal hernias, which overall account for less than 6% of small bowel obstruction. In adults, they are most often iatrogenic or post-traumatic.

The Roux-en-Y gastric by-pass is a procedure used in bariatric surgery. It is based on the creation of a gastric pouch out of a small portion of the stomach which is attached directly to the distal ileum, by-passing the duodenum and large part of small bowel.

Prospective diagnosis of a spontaneous transomental hernia is difficult and relies on very subtle CT findings.

This article provides information about transomental hernias and clues to their diagnosis by CT. Description of CT findings of this rare type of hernia may help the readers to differentiate it from a small bowel volvulus and to make a timely prospective diagnosis in order to avoid a delayed surgical management.

P- Reviewers: Bartalena T, Pinto A, Razek AA, Triantopoulou C S- Editor: Cui XM L- Editor: Roemmele A E- Editor: Wang CH

| 1. | Ghiassi S, Nguyen SQ, Divino CM, Byrn JC, Schlager A. Internal hernias: clinical findings, management, and outcomes in 49 nonbariatric cases. J Gastrointest Surg. 2007;11:291-295. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 59] [Cited by in RCA: 62] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Martin LC, Merkle EM, Thompson WM. Review of internal hernias: radiographic and clinical findings. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2006;186:703-717. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 360] [Cited by in RCA: 370] [Article Influence: 19.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Villalona GA, Diefenbach KA, Touloukian RJ. Congenital and acquired mesocolic hernias presenting with small bowel obstruction in childhood and adolescence. J Pediatr Surg. 2010;45:438-442. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Renvall S, Niinikoski J. Internal hernias after gastric operations. Eur J Surg. 1991;157:575-577. [PubMed] |

| 5. | Yang DH, Chang WC, Kuo WH, Hsu WH, Teng CY, Fan YG. Spontaneous internal herniation through the greater omentum. Abdom Imaging. 2009;34:731-733. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Chou CK, Mak CW, Wu RH, Chang JM. Combined transmesocolic-transomental internal hernia. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2005;184:1532-1534. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Takeyama N, Gokan T, Ohgiya Y, Satoh S, Hashizume T, Hataya K, Kushiro H, Nakanishi M, Kusano M, Munechika H. CT of internal hernias. Radiographics. 2005;25:997-1015. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 215] [Cited by in RCA: 195] [Article Influence: 10.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Duda JB, Bhatt S, Dogra VS. Utility of CT whirl sign in guiding management of small-bowel obstruction. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2008;191:743-747. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 52] [Cited by in RCA: 56] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Gollub MJ, Yoon S, Smith LM, Moskowitz CS. Does the CT whirl sign really predict small bowel volvulus: Experience in an oncologic population. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 2006;30:25-32. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 50] [Cited by in RCA: 51] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Blachar A, Federle MP, Dodson SF. Internal hernia: clinical and imaging findings in 17 patients with emphasis on CT criteria. Radiology. 2001;218:68-74. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 245] [Cited by in RCA: 224] [Article Influence: 9.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Sandhu PS, Joe BN, Coakley FV, Qayyum A, Webb EM, Yeh BM. Bowel transition points: multiplicity and posterior location at CT are associated with small-bowel volvulus. Radiology. 2007;245:160-167. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Chou CK, Wu RH, Mak CW, Lin MP. Clinical significance of poor CT enhancement of the thickened small-bowel wall in patients with acute abdominal pain. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2006;186:491-498. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Sheedy SP, Earnest F, Fletcher JG, Fidler JL, Hoskin TL. CT of small-bowel ischemia associated with obstruction in emergency department patients: diagnostic performance evaluation. Radiology. 2006;241:729-736. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 131] [Cited by in RCA: 129] [Article Influence: 7.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Hayakawa K, Tanikake M, Yoshida S, Yamamoto A, Yamamoto E, Morimoto T. CT findings of small bowel strangulation: the importance of contrast enhancement. Emerg Radiol. 2013;20:3-9. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 44] [Cited by in RCA: 45] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Macari M, Chandarana H, Balthazar E, Babb J. Intestinal ischemia versus intramural hemorrhage: CT evaluation. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2003;180:177-184. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 53] [Cited by in RCA: 43] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Delabrousse E, Couvreur M, Saguet O, Heyd B, Brunelle S, Kastler B. Strangulated transomental hernia: CT findings. Abdom Imaging. 2001;26:86-88. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |