Published online Nov 28, 2014. doi: 10.4329/wjr.v6.i11.865

Revised: August 19, 2014

Accepted: September 6, 2014

Published online: November 28, 2014

Processing time: 249 Days and 3.6 Hours

Spectrum of acute renal infections includes acute pyelonephritis, renal and perirenal abscesses, pyonephrosis, emphysematous pyelonephritis and emphysematous cystitis. The chronic renal infections that we routinely encounter encompass chronic pyelonephritis, xanthogranulomatous pyelonephritis, and eosinophilic cystitis. Patients with diabetes, malignancy and leukaemia are frequently immunocompromised and more prone to fungal infections viz. angioinvasive aspergillus, candida and mucor. Tuberculosis and parasitic infestation of the kidney is common in tropical countries. Imaging is not routinely indicated in uncomplicated renal infections as clinical findings and laboratory data are generally sufficient for making a diagnosis. However, imaging plays a crucial role under specific situations like immunocompromised patients, treatment non-responders, equivocal clinical diagnosis, congenital anomaly evaluation, transplant imaging and for evaluating extent of disease. We aim to review in this article the varied imaging spectrum of renal inflammatory lesions.

Core tip: Imaging in renal infections is challenging, given the relatively non-specific nature of findings in majority of the cases. A careful assessment of clinical situation in question is essential to accurately choose the imaging modality which would provide most information. In this review we discuss the appropriateness of specific imaging modalities, to allow the radiologist to choose the best modality for a given clinical situation. In addition, some entities such as acute pyelonephritis, Xanthogranulomatous pyelonephritis and emphysematous pyelonephritis have some specific imaging features. In this review we describe and illustrate such specific features, to facilitate their recognition when present.

- Citation: Das CJ, Ahmad Z, Sharma S, Gupta AK. Multimodality imaging of renal inflammatory lesions. World J Radiol 2014; 6(11): 865-873

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1949-8470/full/v6/i11/865.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4329/wjr.v6.i11.865

Renal infections range from mild to severe, acute to chronic (Table 1) and may be associated with predisposing risk factors like diabetes mellitus, human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), leukemia, vesico-ureteric reflux and staghorn calculi.

| Acute | Chronic | Others |

| Acute pyelonephritis | Chronic pyelonephritis | Tuberculosis |

| Focal nephritis | Xanthogranulomatous pyelonephritis | Fungal |

| Abscess | Malakoplakia | |

| Emphsematous pyelonephritis | Eosinophilic cystitis | |

| Papillary necrosis | ||

| Pyonephrosis |

Acute infections include acute pyelonephritis which may be focal or diffuse, may resolve with time or worsen to abscess formation depending on the treatment rendered and immune status of the patient. Immunocompromised state might predispose an individual to more severe and life threatening conditions like emphysematous pyelonephritis which may warrant a nephrectomy. An obstructing pathology with a superimposed infection may lead to pyonephrosis for which drainage is the treatment of choice. Renal infections may take a turn for the worse in a chronic irreversibly damaging form like chronic pyelonephritis and xanthogranulomatous pyelonephritis. Tuberculosis involves the kidney with calyceal irregularity being the earliest manifestation, later leading to scarring, fibrosis and infundibular and ureteric stricture formation. Immunocompromised individuals are particularly predisposed to fungal infections, the most common organisms being Candida, Aspergillus and Mucor. Some rare inflammatory conditions encountered are malakoplakia and eosinophilic cystitis.

Acute infection is usually diagnosed based on clinical symptoms and laboratory data without imaging examinations. Hence, imaging is not routinely indicated in uncomplicated renal infections. However, imaging plays a pivotal role in evaluating infections in situations like immunocompromised state, treatment non-responders, congenital anomaly evaluation, and post transplant for evaluating extent of the disease. We wish to review in this article the varied imaging spectrum of renal inflammatory lesions.

Imaging is not routinely indicated in urinary tract infections, however with severe symptoms, high risk immunocompromised state, diabetic patients and antibiotic non-responders, it becomes necessary[1]. Plain radiography may provide evidence of gas in the renal area in emphysematous pyelonephritis or abscess and the typical mass like calcification in end stage renal tuberculosis (Putty kidney). Ultrasound (US) is the initial screening modality and is used for guiding interventions as well. The role of intravenous urography (IVU) has diminished lately, however it still remains the best modality to diagnose calyceal irregularity of early tuberculosis, papillary necrosis and to evaluate congenital anomalies. Computed tomography (CT) is the gold standard for diagnosis and assessment of severity of acute pyelonephritis and its complications. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is indicated in pregnancy and patients with contraindication to iodinated contrast such as transplant recipients. Diffusion weighted MRI (DW-MRI) has been applied to differentiate hydronephrosis from pyonephrosis as well as to detect infected cysts and tumors.

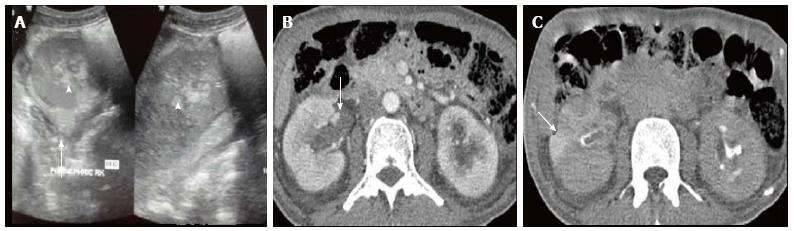

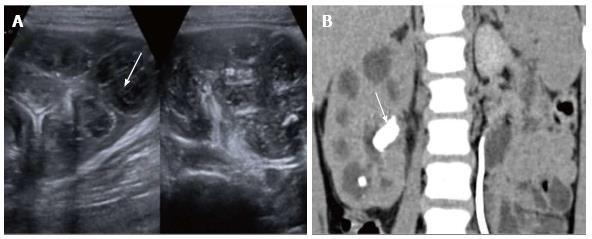

Acute pyelonephritis is usually diagnosed based on clinical symptoms and laboratory data without imaging examinations. In many cases of mild acute pyelonephritis, enhanced CT or ultrasonography may show no abnormal findings. The recommended phases of CT scan for evaluating renal infections are a non-contrast scan, nephrographic phase at 50-90 s and excretory phase at 2 min if there is obstruction[2]. Striated nephrogram which is an appearance described for acute pyelonephritis shows discrete rays of alternating hypoattenuation and hyperattenuation radiating from the papilla to the cortex along the direction of the excretory tubules (Figures 1 and 2). This appearance is ascribed to the decreased flow of contrast due to stasis and eventual hyperconcentration in the infected tubules[3]. Striated nephrogram is not specific and is also seen in some other conditions like renal vein thrombosis, ureteric obstruction and contusion[4]. Pyelonephritis may manifest as wedge shaped zones of decreased attenuation or a hypodense mass in its focal form (Figure 3). The diffuse form of acute pyelonephritis may cause global enlargement, poor enhancement of renal parenchyma, absent excretion of contrast and streakiness of fat. Hemorrhagic bacterial nephritis which is relatively uncommon shows hyperattenuating areas representing parenchymal bleeding on non-contrast scan[5].

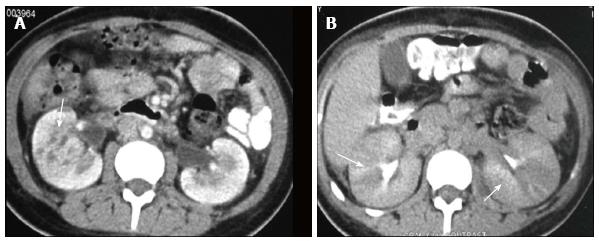

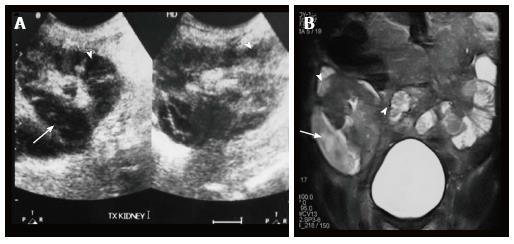

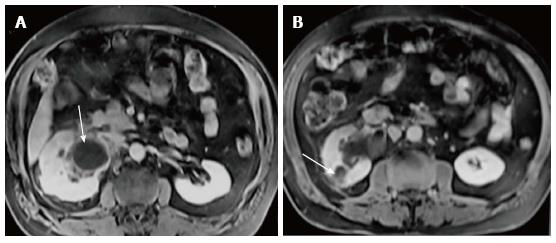

Renal and perinephric abscesses develop as a complication of focal pyelonephritis or hematogenous infection. Early abscess appears as a poorly marginated non-enhancing area of decreased attenuation. A mature abscess shows a sharply marginated, complex cystic mass with necrosis and a peripheral enhancing rim[6]. US may show internal echoes, septations and loculations (Figure 4). DW-MRI can readily pick up abscesses showing restriction of diffusion (Figure 5). In a transplant patient DW-MRI has an important role to play as contrast may be contraindicated due to deranged renal parameters (Figure 6).

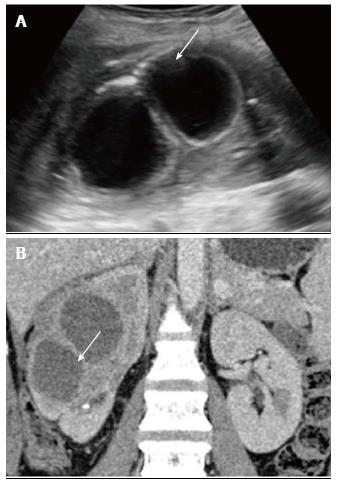

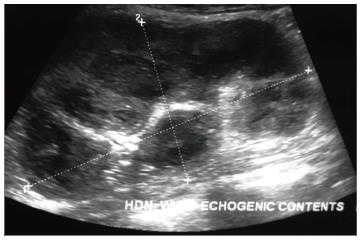

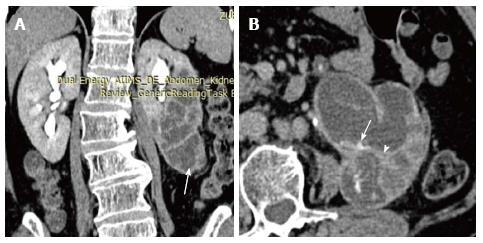

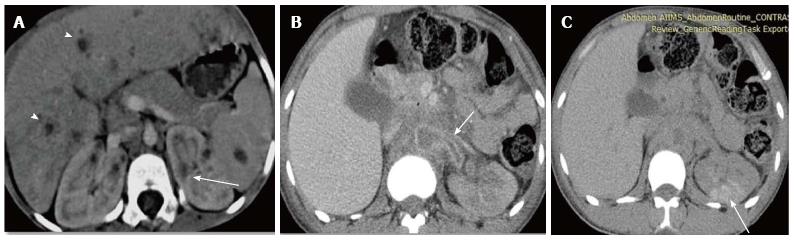

Pyonephrosis is pus collection in an obstructed collecting system, the cause of obstruction being calculus, stricture, tumour or congenital anomaly. US shows dilated pelvicalyceal system (PCS) with debris and fluid-fluid levels within (Figure 7)[1]. On CT, high density of urine in dilated PCS with contrast layering, parenchymal or perinephric inflammatory changes and thickening of pelvic wall suggests infection (Figure 8). DW-MRI may have an additional role in distinguishing hydronephrosis from pyonephrosis as pyonephrosis tends to show restricted diffusion (Figure 9)[7]. Contrast enhanced MRI may show enhancement and wall thickening of the renal pelvis (Figure 10).

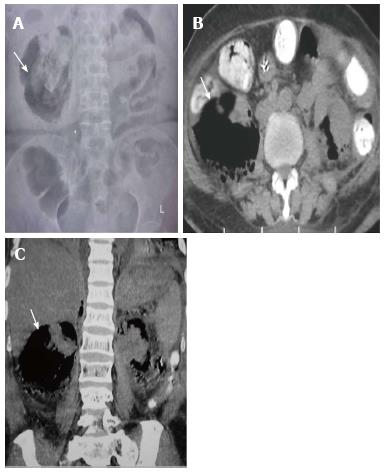

Xanthogranulomatous pyelonephritis is a chronic granulomatous process commonly associated with recurrent E. coli and Proteus mirabilis infection affecting middle aged females and children. Most (90%) of the affected individuals have a staghorn calculus. Pathologically there is replacement of renal parenchyma with foamy macrophages which appear as multiple hypoechoic masses on sonography and as low attenuation rounded masses on CT which represent dilated calyces and abscess cavities (Figure 11) filled with pus and debris[8]. It can manifest as either diffuse (80%) or focal (15%) forms which are treated by nephrectomy and partial nephrectomy respectively[9]. Typical features of xanthogranulomatous pyelonephritis are presence of a central calculus, expansion of the calices with hypodense material in a non-functioning enlarged kidney and inflammatory changes in the perinephric fat. Atypical features include absence of calculi (10%), focal instead of diffuse involvement (10%) and renal atrophy instead of enlargement.

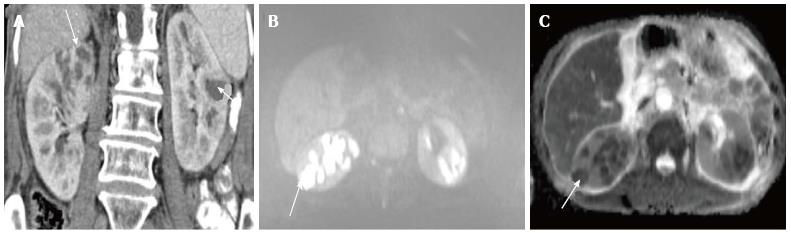

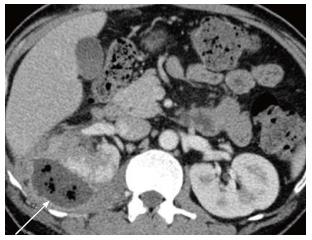

Emphysematous pyelonephritis is a life threatening, necrotising infection with gas formation and is associated with diabetes mellitus or immunocompromised state. The presence of gas is attributed to fermentation by bacteria in the presence of high glucose levels[10]. USG shows non-dependent echoes within the parenchyma and collecting system with dirty shadowing. However, USG is not sensitive to small amounts of gas (Figure 12). CT is performed for evaluating severity, extent of disease, parenchymal destruction, fluid collections and abscess formation. It is divided into two forms depending on severity and prognosis. Type 1 is the more severe type with a mortality rate of 80%. It is characterised by severe parenchymal destruction, intraparenchymal gas and paucity of pus collection (Figure 13). Type 2 is less common and has a lower mortality rate of 20%. It has less parenchymal destruction and renal or perirenal fluid collections (Figure 14). A comparison of the types of emphysematous pyelonephritis is presented in Table 2.

| TYPE 1 -33% | TYPE 2 -66% | |

| Parenchymal destruction | Severe – streaky gas radiating from medulla to cortex with crescent of subcapsular gas | Less |

| Fluid collection | None as the reduced immune response limits pus collection | Renal or perirenal fluid collection is characteristic |

| Mortality | 80% | 20% |

| Treatment | Nephrectomy | Aggressive medical treatment with percutaneous drainage |

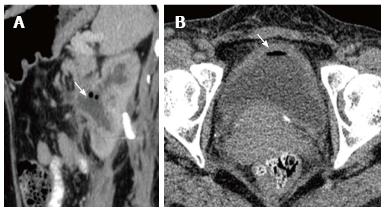

Emphysematous pyelitis is usually accompanied by obstruction due to calculus, neoplasm or stricture and 50% of the affected patients are diabetics[10-12]. CT shows gas within the dilated PCS and urinary bladder (Figure 15 A). Emphysematous cystitis shows an air fluid level in the bladder lumen or linear streaks of air in the bladder wall (Figure 15B). Before making a diagnosis of emphysematous cystitis, history of instrumentation must be ruled out.

It is important to make the distinction between emphysematous pyelitis and pyelonephritis as the former is a less aggressive infection and does not require nephrectomy. In pyelitis, air is limited to PCS while in pyelonephritis it enters the parenchyma.

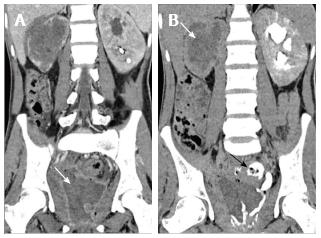

Chronic pyelonephritis may be caused by reflux of infected urine in childhood, recurrent infections or as a result of a remote single infection[13]. Imaging shows focal polar scars with underlying calyceal distortion with global atrophy and hypertrophy of residual tissue (Figure 16)[14]. Lobar infarcts can be differentiated by their lack of calyceal involvement. Fetal lobulations are differentiated by depressions lying between calyces rather than overlying calyces

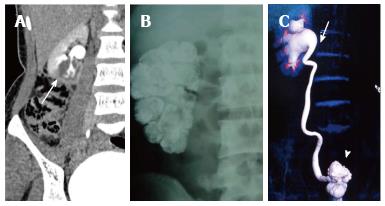

Renal tuberculosis (TB) may occur due to hematogenous dissemination. In half of the affected patients of genitourinary TB, there may be no lung involvement[15]. The earliest finding in TB which can be picked up on Intravenous Urography (IVU) is caliectasis with a feathery contour, later appearing as a phantom calyx or a cavity communicating with a deformed calyx (Figure 17A). These findings can also be picked up on CT. Over the course of the disease, the granulomas coalesce forming mass like lesions (tuberculoma) which may rupture into the PCS[16]. Eventually as the disease evolves, fibrosis ensues leading to infundibular stenosis. In the late stage, the kidney either becomes calcified or shrunken (putty kidney) (Figure 17B) or an enlarged sac with caseous material (case cavernous type autonephrectomy). Ureteric involvement may manifest as wall thickening causing strictures and shortening leading to a beaded appearance. Bladder involvement results in a contracted thimble shape with multiple diverticulae (Figure 17C).

Schistosomiasis can appear in the acute phase as nodular bladder wall thickening, later causing it to become contracted, fibrotic and thick walled with curvilinear calcifications. This chronic phase of schistosomiasis is considered to be premalignant. Liver is the most common organ involved by hydatid disease while renal involvement comprises only 5% of patients. Hydatid disease affecting the kidney may appear as a unilocular or multilocular cystic lesion(s) with or without peripheral calcification[17] (Figure 18). Occasionally on communication with the pelvicalyceal system (PCS) it may lead to hydatiduria.

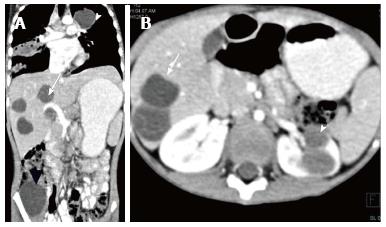

Fungal infection of the urinary tract is a severe life threatening infection particularly affecting patients with diabetes mellitus, haematological malignancy, HIV or other immunocompromised status. The common fungal organisms are Candida and Aspergillus which may be acquired by hematogenous or ascending urinary tract infection. There is formation of multiple renal abscesses appearing as hypoattenuating lesions with a striated nephrogram signifying acute pyelonephritis (Figure 19A). There can also be conglomeration of fungal hyphae and inflammatory cells into a fungal ball which appears as an irregular filling defect in the collecting system[1]. Diagnosis requires demonstration of fungi in tissues. Mucor is a rare organism which has a tendency to invade vessels and cause infarction with high mortality requiring combined surgical and aggressive medical management to improve outcome (Figure 19B, C)[18]. Pneumocystis carini infection in HIV patients presents as diffuse punctate calcifications in kidneys and organs of the reticuloendothelial system[19].

Eosinophilic cystitis is a rare chronic inflammatory disease of urinary bladder due to eosinophil infiltration into the bladder wall leading to fibrosis and muscle necrosis[20]. It clinically presents with hematuria, frequency and irritative symptoms. The mean age at diagnosis is 41.6 years with an equal sex distribution[21].

On imaging, there is diffuse bladder wall thickening which is often more than 10 mm with characteristic preservation of the mucosal line and enhancement on delayed images (Figure 20)[22,23]. This entity is often confused with a neoplastic etiology, therefore biopsy is essential. There may be associated diffuse or segmental bowel wall thickening and hepatic nodules[22].

Over the years imaging modalities used for renal infections have evolved from USG and IVU to CT and MRI. CT remains the mainstay in evaluation of inflammatory disease of kidney and urinary bladder. Ultrasonography forms an excellent screening tool for evaluation in the emergency setting. An IVU continues to be invaluable in some indications like tuberculosis. Upcoming role of DW-MRI deserves mention in identifying abscesses and differentiating pyonephrosis from hydronephrosis.

P- Reviewer: Gao BL, Tsushima Y S- Editor: Song XX L- Editor: A E- Editor: Lu YJ

| 1. | Kawashima A, Sandler CM, Goldman SM, Raval BK, Fishman EK. CT of renal inflammatory disease. Radiographics. 1997;17:851-866; discussion 867-868. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 114] [Cited by in RCA: 67] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Stunell H, Buckley O, Feeney J, Geoghegan T, Browne RF, Torreggiani WC. Imaging of acute pyelonephritis in the adult. Eur Radiol. 2007;17:1820-1828. [PubMed] |

| 3. | Gold RP, Mcclennan BL, Kenney PJ, Breatnach ES, Stanley RJ, Lebowitz RI. Acute infections of the renal parenchyma. Clinical urography. Philadelphia, Pa: Saunders 1990; 799-821. |

| 4. | Saunders HS, Dyer RB, Shifrin RY, Scharling ES, Bechtold RE, Zagoria RJ. The CT nephrogram: implications for evaluation of urinary tract disease. Radiographics. 1995;15:1069-185; discussion 1069-1085. [PubMed] |

| 5. | Rigsby CM, Rosenfield AT, Glickman MG, Hodson J. Hemorrhagic focal bacterial nephritis: findings on gray-scale sonography and CT. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1986;146:1173-1177. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 45] [Cited by in RCA: 45] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Browne RF, Zwirewich C, Torreggiani WC. Imaging of urinary tract infection in the adult. Eur Radiol. 2004;14 Suppl 3:E168-E183. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Cova M, Squillaci E, Stacul F, Manenti G, Gava S, Simonetti G, Pozzi-Mucelli R. Diffusion-weighted MRI in the evaluation of renal lesions: preliminary results. Br J Radiol. 2004;77:851-857. [PubMed] |

| 8. | Loffroy R, Guiu B, Watfa J, Michel F, Cercueil JP, Krausé D. Xanthogranulomatous pyelonephritis in adults: clinical and radiological findings in diffuse and focal forms. Clin Radiol. 2007;62:884-890. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 73] [Cited by in RCA: 65] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Kim JC. US and CT findings of xanthogranulomatous pyelonephritis. Clin Imaging. 2001;25:118-121. [PubMed] |

| 10. | Grayson DE, Abbott RM, Levy AD, Sherman PM. Emphysematous infections of the abdomen and pelvis: a pictorial review. Radiographics. 2002;22:543-561. [PubMed] |

| 11. | Kiris A, Ozdemir H, Bozgeyik Z, Kocakoc E. Ultrasonographic target appearance due to renal calculi containing gas in emphysematous pyelitis. Eur J Radiol Extra. 2004;52:119-21. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Joseph RC, Amendola MA, Artze ME, Casillas J, Jafri SZ, Dickson PR, Morillo G. Genitourinary tract gas: imaging evaluation. Radiographics. 1996;16:295-308. [PubMed] |

| 13. | Craig WD, Wagner BJ, Travis MD. Pyelonephritis: Radiologic-Pathologic review in adults. Radiographics. 2008;28:255–276. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 288] [Cited by in RCA: 232] [Article Influence: 13.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Goldman SM. Acute and chronic urinary infection: present concepts and controversies. Urol Radiol. 1988;10:17-24. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Becker JA. Renal tuberculosis. Urol Radiol. 1988;10:25-30. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Hammond NA, Nikolaidis P, Miller FH. Infectious and inflammatory diseases of the kidney. Radiol Clin North Am. 2012;50:259-270, vi. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Pedrosa I, Saíz A, Arrazola J, Ferreirós J, Pedrosa CS. Hydatid disease: radiologic and pathologic features and complications. Radiographics. 2000;20:795-817. [PubMed] |

| 18. | Sharma R, Shivanand G, Kumar R, Prem S, Kandpal H, Das CJ, Sharma MC. Isolated renal mucormycosis: an unusual cause of acute renal infarction in a boy with aplastic anaemia. Br J Radiol. 2006;79:e19-e21. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Radin DR, Baker EL, Klatt EC, Balthazar EJ, Jeffrey RB, Megibow AJ, Ralls PW. Visceral and nodal calcification in patients with AIDS-related Pneumocystis carinii infection. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1990;154:27-31. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 93] [Cited by in RCA: 60] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Teegavarapu PS, Sahai A, Chandra A, Dasgupta P, Khan MS. Eosinophilic cystitis and its management. Int J Clin Pract. 2005;59:356-360. [PubMed] |

| 21. | Pomeranz A, Eliakim A, Uziel Y, Gottesman G, Rathaus V, Zehavi T, Wolach B. Eosinophilic cystitis in a 4-year-old boy: successful long-term treatment with cyclosporin A. Pediatrics. 2001;108:E113. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Kim MS, Park H, Park CS, Lee EJ, Rho MH, Park NH, Joh J. Eosinophilic cystitis associated with eosinophilic enterocolitis: case reports and review of the literature. Br J Radiol. 2010;83:e122-e125. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Leibovitch I, Heyman Z, Ben Chaim J, Goldwasser B. Ultrasonographic detection and control of eosinophilic cystitis. Abdom Imaging. 1994;19:270-271. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |