Revised: November 11, 2013

Accepted: December 17, 2013

Published online: January 28, 2014

Processing time: 130 Days and 14.1 Hours

Paragangliomas are extra-adrenal pheochromocytomas that derive from chromaffin cells and arise along the sympathetic paraganglia in the body. In the majority of cases, they are secretory tumors and most commonly present with palpitations. Plasma metanephrines are the standard screening tests for making the diagnosis which is confirmed by pathology. Imaging plays a very important role in establishing the diagnosis. However, there is no specific feature on imaging for paragangliomas; the vascularity of the tumor should show as hyper-enhancing lesions but this is not always the case. The diagnostic value of PET is yet a matter of debate. We present a very rare case of a paraganglioma arising at the renal hilum, splaying the renal artery and vein and causing vascular compromise to the left kidney. The patient presented with an atypical presentation of unrelenting fever that was followed by acute colicky pain. Based on imaging and blood metanephrine levels, the diagnosis of paraganglioma was made. Resection of the tumor was achieved and the patient is now asymptomatic.

Core tip: Chromaffin cell tumors are very rare tumors, the majority of which derive from catecholamine secreting cells in the adrenal glands. Extra-adrenal paragangliomas comprise around 15% of chromaffin cell tumors; they usually arise from sympathetic paraganglia throughout the body. We present a very rare case with the location and presentation of a paraganglioma arising at the renal hilum splaying the renal artery and vein and causing vascular compromise to the left kidney.

- Citation: Yehia ZAA, Sayyid RK, Haydar AA. Renal hilar paraganglioma: A case report. World J Radiol 2014; 6(1): 15-17

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1949-8470/full/v6/i1/15.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4329/wjr.v6.i1.15

Paragangliomas comprise a rare category of chromaffin cell tumors. They are extra-adrenal pheochromocytomas usually arising along the sympathetic paraganglia in the body. The rarity of these tumors can easily mislead the pre-operative diagnosis, leading to a drastic outcome especially when it arises in atypical locations. There is no specific well described feature on imaging for paraganglioma; the vascularity of the tumor should reveal a hyper-enhancing mass but this is not always the case[1]. Despite premedication, a significant percentage of patients experience considerable intraoperative hemodynamic complications; it is therefore essential to have a high index of suspicion in making the diagnosis of a paraganglioma in the light of atypical tumor location and unspecific symptoms[2].

The patient is a previously healthy 32-year-old woman. She presented with a 10 d history of headache, nausea, vomiting and generalized weakness, followed by acute onset colicky renal pain and low grade fever. Physical examination was non-remarkable except for tachycardia (HR: 130-140).

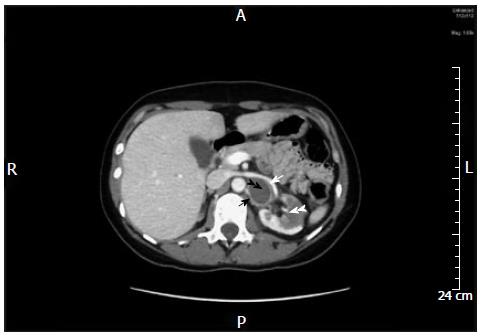

Patient had leukocytosis (WBC: 17000), elevated inflammatory markers (CRP: 11.485 mg/dL, normal: 0-1 mg/dL) and the other tests were unremarkable. CT abdomen revealed a 3.3 cm × 3.3 cm × 2.5 cm mass with hypodense center and ring enhancement at the renal hilum splaying the renal artery and the renal vein and causing vascular compromise to the left kidney with secondary focal lower pole infarction (Figure 1).

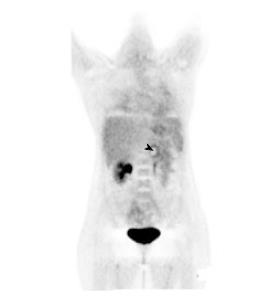

Blood metanephrine level was then obtained and found to be elevated (0.88; normal: less than 0.37). PET-CT revealed radiotracer uptake at the periphery of the mass (Figure 2). CT guided FNA was done and showed atypical epithelioid malignant cells.

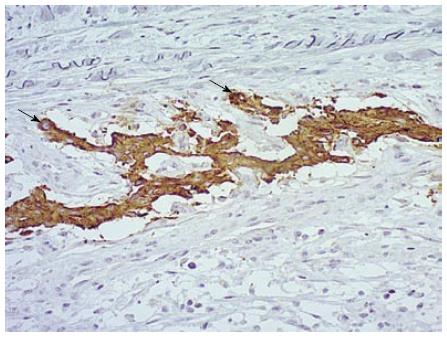

The patient was pre-medicated with an alpha blocker and underwent surgery four days later for a suspected extra-adrenal pheochromocytoma. Total left nephrectomy and excision of the mass was done. Pathology revealed a paraganglioma (Figure 3).

Her post-operative course was uneventful. Her headaches disappeared completely and her pulse returned to normal, despite discontinuation of the beta blocker.

Paragangliomas usually present along the sympathetic chain in the abdomen, particularly in the vicinity of the aorta and less commonly in the thorax or head and neck[2,3]. They can be functional-secreting catecholamines or nonfunctional. Paragangliomas are secretory in more than 50% of cases, the majority of which present with palpitations[3,4].

Other typical symptoms include episodic hypertension, headache and diaphoresis. Paroxysmal hypertension is seen only in 50% of these patients[3]. Unspecific presenting symptoms such as fever and lumbar pain have been reported with cases of retroperitoneal paragangliomas[4,5]. The laboratory workup of patients with pheochromocytomas and extra-adrenal paragangliomas (PPGLs) has conventionally relied on biochemical measurements of tumor secretory products or their metabolites. Histopathology and immunohistochemistry remain the gold standard for making the definitive diagnosis[6-8].

Approximately 10% of pheochromocytomas and paragangliomas are malignant; nevertheless, this often cannot be determined on a biochemical or histological basis. Malignancy in these tumors is defined by the presence of local invasion on gross or microscopic examination at the time of resection, or much more commonly by the presence of metastases[6,7,9].

Our patient presented with a 10 d history of headache and fever, followed by acute onset colicky renal pain. She was tachycardic but her blood pressure was normal on all measurements taken. The acute pain, in association with fever, headache, nausea and vomiting, together with the hypodense mass in the kidney, led us to consider an infectious ongoing process.

Plasma free metanephrine and normetanephrine or urine metanephrine are the first screening tests to make the diagnosis of a paraganglioma[7]. Our patient had elevated plasma metanephrine level with no elevation of normetanephrine. Imaging studies such as CT or magnetic resonance imaging are essential before surgery for confirmation and for further assessment of the location, size and possible metastasis. PET-CT provides precise anatomic and metabolic information and recently has become increasingly relied upon. In the initial evaluation of pheochromocytomas, it was validated that PET-CT complements other modalities. However, the value of PET alone in determining metastatic disease is still vague due to the rarity of the tumor[6,9,10].

According to the NCCN guidelines, the mainstay of treatment of paragangliomas is total resection when possible. If not, cytoreductive resection followed by radiation or systemic chemotherapy should be offered, depending on the extent of the metastasis[8]. In our case, the left kidney’s compromise by the tumor and the location of the tumor necessitated a total nephrectomy to be performed. There was no evidence of vascular invasion and the symptoms totally disappeared after the resection.

Paragangliomas are more likely to be malignant than pheochromocytomas (40% vs 10%)[3,7]. According to the literature, the presence of confluent necrosis and the secretory nature of the tumor, both of which are present in our patient, are predictors of malignancy[8]. However, the differentiation between malignant and benign paragangliomas is still debatable and evidence of metastasis is the only definitive criterion to label the tumor as malignant so far[3,8,10].

Surveillance is advised every 6-12 mo in the first 5 years post resection and then annually until 10 years post resection. In our case, it is recommended to follow up with history, physical exam and blood pressure measurements, as well as metanephrine levels. Imaging should be done if needed in case of new clinical findings. Patients under the age of 45, or those with multifocal, bilateral or recurrent lesions, are more likely to have a heritable mutation and in these cases, genetic counseling and testing are recommended, according to NCCN 2013 guidelines[8].

The patient presented with a 10 d history of headache, nausea, vomiting and generalized weakness, followed by acute onset colicky renal pain and low grade fever.

The patient’s symptoms were very unspecific and the presence of unrelenting fever along with the acute colicky renal pain pointed to an infectious process in the vicinity of the kidney.

An infectious process in the abdomen causing this pain and fever was first on the differential, followed by renal colic. Renal cell carcinoma was also ruled out.

Blood tests were negative except for elevated inflammatory markers and blood metanephrine levels.

Computed tomography scan of the abdomen showed a hypodense mass with ring enhancement on the renal hilar area splaying the renal artery and vein. Positron emission tomography scan was done and demonstrated radiotracer uptake at the periphery of the mass.

FNA was done and showed atypical epithelioid malignant cells. Pathology of the excised mass revealed a paraganglioma.

The patient was pre-medicated with an alpha blocker and then 4 d later underwent left nephrectomy and excision of the mass was performed.

The Joynt et al article “Paragangliomas, etiology, presentation and management” published in 2009 provides a brief but cumulative overview on the case topic.

A paraganglioma is a rare tumor that originate from chromaffin cells of sympathetic chain; it can be found anywhere along the sympathetic chains in the body.

One lesson that the authors learned from this case is to consider paraganglioma in the differential when a patient presents with vague symptoms and an abdominal mass.

The manuscript presents a rare case of a renal hilar paraganglioma demonstrating the steps to making the diagnosis and it provides some literature review regarding the management and follow up of such a rare tumor. The case may not add much to the existing literature but it certainly highlights an original substance to learn from.

P- Reviewers: Chen F, Gholamrezanezhad A, Lakatos PL S- Editor: Qi Y L- Editor: Roemmele A E- Editor: Wang CH

| 1. | Kinney MA, Warner ME, vanHeerden JA, Horlocker TT, Young WF, Schroeder DR, Maxson PM, Warner MA. Perianesthetic risks and outcomes of pheochromocytoma and paraganglioma resection. Anesth Analg. 2000;91:1118-1123. [PubMed] |

| 2. | Pagni F, Galbiati E, Bono F, Di Bella C. Renal hilus paraganglioma: a case report and brief review. Pathologica. 2009;101:89-92. [PubMed] |

| 3. | Joynt KE, Moslehi JJ, Baughman KL. Paragangliomas: etiology, presentation, and management. Cardiol Rev. 2009;17:159-164. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 53] [Cited by in RCA: 66] [Article Influence: 4.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 4. | Chandra V, Thompson GB, Bower TC, Taler SJ. Renal artery stenosis and a functioning hilar paraganglioma: a rare cause of renovascular hypertension--a case report. Vasc Endovascular Surg. 2004;38:385-390. [PubMed] |

| 5. | Davies LL, Fitchett JM, Jones D. Fever of unknown origin: a rare retroperitoneal cause. BMJ Case Rep. 2012;2012:pii: bcr0320126122. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Lee KY, Oh YW, Noh HJ, Lee YJ, Yong HS, Kang EY, Kim KA, Lee NJ. Extraadrenal paragangliomas of the body: imaging features. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2006;187:492-504. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 155] [Cited by in RCA: 152] [Article Influence: 8.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Eisenhofer G, Tischler AS, de Krijger RR. Diagnostic tests and biomarkers for pheochromocytoma and extra-adrenal paraganglioma: from routine laboratory methods to disease stratification. Endocr Pathol. 2012;23:4-14. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 78] [Cited by in RCA: 73] [Article Influence: 5.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN Guidelines Version 1. USA: NCCN 2014; Neuroendocrine Tumors 2013, MS23-M25. |

| 9. | Saad FF, Kroiss A, Ahmad Z, Zanariah H, Lau W, Uprimny C, Donnemiller E, Kendler D, Nordin A, Virgolini I. Localization and prediction of malignant potential in recurrent pheochromocytoma/paraganglioma (PCC/PGL) using 18F-FDG PET/CT. Acta Radiol. 2013;Epub ahead of print. [PubMed] |

| 10. | Lin M, Wong V, Yap J, Jin R, Leong P, Campbell P. FDG PET in the evaluation of phaeochromocytoma: a correlative study with MIBG scintigraphy and Ki-67 proliferative index. Clin Imaging. 2013;37:1084-1088. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |