Revised: December 19, 2012

Accepted: December 22, 2012

Published online: February 28, 2013

Processing time: 188 Days and 17.6 Hours

We report three cases of intra-articular infection which followed injection for magnetic resonance arthrography. In an effort to reduce the risk of arthrogram related infection, representatives from radiology, infectious disease medicine, and microbiology departments convened to analyze the contributing factors. The proposed source was oral contamination from barium swallow studies which preceded the arthrogram injections in the same room. We propose safety measures to reduce incidence of arthrogram related infections.

- Citation: Vollman AT, Craig JG, Hulen R, Ahmed A, Zervos MJ, Holsbeeck MV. Review of three magnetic resonance arthrography related infections. World J Radiol 2013; 5(2): 41-44

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1949-8470/full/v5/i2/41.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4329/wjr.v5.i2.41

Magnetic resonance (MR) arthrography is an established modality useful for the evaluation of internal joint derangements[1]. It is a well tolerated procedure with a very low reported incidence of associated infections. In a review of 126 000 arthrograms, Newberg et al[2] found 3 cases of associated septic arthritis and one case of cellulitis.

We report three cases of intra-articular infection at our institution which developed after injection for MR arthrography in a 14 mo time frame including two infections that occurred within 10 d. We share the results of an interdisciplinary root cause analysis among the infectious disease, microbiology, and radiology departments to determine the risk factors and propose measures to avoid future infections.

Approval from our institutional review board was obtained prior to the retrospective review of the three cases infection related to MR arthrography.

The charts of the three patients who developed infection were reviewed by the Departments of Infectious Disease, Microbiology, and Radiology. Additional history which was acquired directly from the patients in the fluoroscopy suite at the time of the procedure was also reviewed.

All of the cases were performed in a Siemens Artis fluoroscopy suite with aseptic technique (Figure 1). The skin was prepared with chlorhexidine gluconate and a sterile drape was placed over the field. Operators all wore surgical caps and masks in addition to sterile gowns and gloves.

The skin was anesthetized with 2-5 mL of lidocaine 0.5% local anesthetic. The radiologist performing the procedure prepared the trays and injectate. The constrast vials were single use vials that were only for one patient and were discarded after each procedure. Injectate was then drawn under sterile technique and included Magnevist diluted in normal saline (Bayer Healthcare; gadopentetate dilution 1/250), Optiray 350 (Mallinckrodt, Inc.) and a tiny amount of epinephrine (1/1000). Then under fluoroscopic guidance, a 20 gauge spinal needle was advanced into the joint and the joint injected with the contrast mixture. Sites of injection included the right knee, right shoulder, and left knee.

For further analysis, infection control personnel also directly observed radiologists performing other routine arthrography cases to document the sterile technique and determine the need for any changes in infection control practices.

A 46-year-old female presented with right knee pain who had a history of anterior cruciate ligament and lateral meniscal tears of the right knee for which she had several surgical procedures. She presented for MR arthrogram of her right knee to evaluate for re-injury of the knee. She underwent an uneventful injection of approximately 30 mL of the contrast mixture into her right knee prior to her MRI. She left the hospital in unchanged condition.

Within 24 h of the injection the patient presented to emergency room (ER) with a right knee effusion and severe pain. The joint was aspirated and demonstrated a cell count of 70 000 white blood cell (WBC)/mm3. The synovial fluid grew Streptococcus crista. Incision and drainage was performed and the patent was treated with vancomycin and ceftriaxone. She was discharged after 2 d in the hospital. Her course was complicated by severe stiffness of her knee postoperatively which eventually resolved after six months of physical therapy. Ultimately she was able to regain full range of motion of her knee and return to work.

A 63-year-old female with a history of arthrography of the left knee presented to evaluate a possible re-tear of her lateral meniscus. The arthrogram injection was also standard and uneventful and she left the hospital in unchanged condition after the magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) exam. After the procedure she presented to an ER at another institution with signs of a septic joint and was transferred back to our institution within 3 d of the original arthrogram procedure. She was found to have a temperature of 38 °C and her knee was painful, swollen, and warm to the touch. Aspirate showed greater than 70 000 WBC/mm3 and grew Streptococcus crista. Incision and drainage was performed arthroscopically and the patient was discharged with a peripherally inserted central catheter (PICC) line on intravenous (IV) ceftriaxone and Augmentin. Within two days of discharge she returned to the emergency room with sepsis and persistence of the knee effusion. Blood cultures were negative as were cultures of the PICC line and joint aspirate. Clostridium difficile toxin was also negative.

Her course was complicated by an acute thrombosis of the left gastrocnemius and basilic veins. She had past medical history of deep venous thrombosis (three years earlier) secondary to heterozygous methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase mutation. She was treated with IV antibiotics for the infection as well as heparin for the thrombosis. After eight days of inpatient care, the patient was discharged on IV ceftriaxone through a PICC line and warfarin. With six months of physical therapy, the patient re-gained range of motion of her knee.

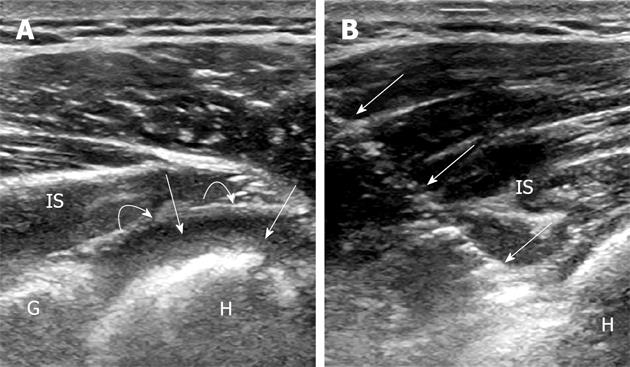

A 27-year-old right hand dominant baseball player presented for a right shoulder arthrogram to evaluate for labral pathology. The arthrogram and MRI were performed without any difficulties. The patient experienced right shoulder pain within 24 h of the procedure. He presented to the ER 48 h after the arthrogram with continuing right shoulder pain and new onset fever. Ultrasound imaging showed a joint effusion and the joint was aspirated (Figure 2). The aspirate had greater than 70 000 WBC/mm3. The synovial fluid grew alpha-hemolytic streptococci. He underwent arthroscopic irrigation and debridement of the right shoulder and was admitted for four days. He was discharged on IV ceftriaxone through a PICC line. After one month he regained full range of motion of his shoulder.

The Radiology Department met with our colleagues in Infectious Disease and Microbiology Departments for consultation of the source of the infections.

The comprehensive review showed that several factors were similar and routine to the cases including the sterile technique, the use of personal protective equipment, the preparation of the injection, and the injection technique. However, it became apparent that all of these injections occurred in the arthrography suite in the afternoon following a morning of barium swallow studies performed on speech pathology patients. There were no other risk factors as determined by the infectious disease physicians that were unique to these particular cases of infection.

Other factors that were discussed included medication contamination and operator causes of contamination. However, several bottles of contrast from the same time frame of the septic joint cases were cultured and came back negative. Single dose vials of contrast were used only for one patient and then thrown out right after the procedure. Both these points make it unlikely the source came from the contrast vials. It was also extremely unlikely that contamination came from the operator during the procedures as the cases were performed by three different radiologists all wearing masks.

The 3 departments worked together and proposed a new protocol for cleaning the room and scheduling procedures (Table 1).

| Procedure room scheduling |

| Avoid performing barium studies and arthrograms in the same procedure room |

| If it is necessary to share a procedure room provide block time slots for barium studies and arthrogram procedures separated by thorough cleaning. |

| Where possible, scheduling arthrograms (along with ports/hickmans, etc.) first thing in the morning prior to barium studies and other potentially contaminating procedures such as enteric stenting/abscess drainage, etc. |

| Procedure room cleaning |

| If the room is to be used for both barium and arthrogram procedures, a thorough cleaning must be performed between barium studies and arthrograms |

| Staffing |

| Limit the staffing options to assistants for all arthrograms |

| Arthrogram kit |

| Replace the kit drape with a larger drape to ensure a maximum sterile barrier |

| Chlorhexidine gluconate swabs should be used to sterilize skin |

| Use proper swab technique: Circle from the inside to the outside |

| Maintain the sterile field |

| Use a sterile sleeve over the image intensifier for each procedure |

| The assistant must wear sterile gloves, hat and mask |

| Ensure that sterile gloves are worn when in contact with the sterile kit, when preparing the injectate |

| All staff must change gloves if they leave the procedure room and re-enter |

| Any tool used to mark the patient prior to the arthrogram must be wiped down with the hospital-approved disinfectant wipes before and after use |

| Any tool that may contact the patient or anything in the sterile field must be sterilized |

Arthrography is considered a safe procedure with an established incidence of infection around 0.003%[2]. With over 400 arthrograms per year are performed at our institution, it was obvious that with three infections in a fourteen month time period and in particular, two within ten days, that there must be additional causal factors. With no idea of the source of this surge in infections, we called on our colleagues in infectious disease and microbiology for consultation.

The exact mechanism of the infections cannot be determined with certainty but it was believed to involve direct contamination of the patients’ skin by oral flora either from the image intensifier or by use of a contaminated arthrogram tray. The majority of the evidence pointed to contamination of the fluoroscopy suite from swallowing studies with inadequate or absent cleaning prior to the arthrograms. Contamination by oral flora was established in a recent report of three cases of meningitis following myelography. In these cases, the assistants did not wear masks and the contamination was from their mouths directly as confirmed by polymerase chain reaction and genotype sequencing[3]. There have also been reported outbreaks of joint sepsis related to using contrast in “single use” vials multiple times to different patients[4]. This however is unlikely in our case because our vials were discarded after each use and cultures were also negative.

At the recommendation of the Infectious Disease Department in the interest of infection control, we have instituted new protocols for arthrogram procedures (Table 1). The fluoroscopy suite must be thoroughly cleaned with and sanitized with a quaternary ammonium product prior to arthrography. Additionally, the room is cleaned with bleach following Clostridium difficile patients. Chlorhexidine is the recommended skin antiseptic because it has a greater reduction in infection rates than povidone-iodine[5]. The image intensifier is now routinely draped with a sterile cover .The number of people in the room is also being limited, and all assistants must wear surgical hats and masks.

In conclusion, our three infections following arthrography caused significant morbidity, although no known long term complications. These infections were likely iatrogenic resulting from concurrent use of the fluoroscopy suite for other non-sterile procedures. In our three cases, the oral flora isolated from joint aspirations presumably resulted from contamination of the room from prior barium swallowing studies with inadequate cleaning of the equipment. The risk of arthrogram related joint infections may be lowered with separation of sterile and non-sterile procedures and with adequate preparation of the fluoroscopy suite.

P- Reviewers Kirby JM, Nouh MR, Yao W, El-Ghar MA, Wang YX, Lian SL S- Editor Gou SX L- Editor A E- Editor Xiong L

| 1. | Schulte-Altedorneburg G, Gebhard M, Wohlgemuth WA, Fischer W, Zentner J, Wegener R, Balzer T, Bohndorf K. MR arthrography: pharmacology, efficacy and safety in clinical trials. Skeletal Radiol. 2003;32:1-12. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 61] [Cited by in RCA: 54] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Newberg AH, Munn CS, Robbins AH. Complications of arthrography. Radiology. 1985;155:605-606. [PubMed] |

| 3. | Srinivasan V, Gertz RE, Shewmaker PL, Patrick S, Chitnis AS, O’Connell H, Benowitz I, Patel P, Guh AY, Noble-Wang J. Using PCR-based detection and genotyping to trace Streptococcus salivarius meningitis outbreak strain to oral flora of radiology physician assistant. PLoS One. 2012;7:e32169. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Online ACDC Special Studies Report 2009. Outbreak of joint injections associated with magnetic resonance arthrograms performed at an outpatient radiology center. Available from: http: //publichealth.lacounty.gov/acd/reports/annual/ 2009SpecialStudies.pdf. |

| 5. | Darouiche RO, Wall MJ, Itani KM, Otterson MF, Webb AL, Carrick MM, Miller HJ, Awad SS, Crosby CT, Mosier MC. Chlorhexidine-Alcohol versus Povidone-Iodine for Surgical-Site Antisepsis. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:18-26. [PubMed] |