Published online Aug 28, 2012. doi: 10.4329/wjr.v4.i8.387

Revised: April 16, 2012

Accepted: April 23, 2012

Published online: August 28, 2012

Two cases with a pancreaticoduodenal arterial aneurysm accompanied with superior mesenteric artery (SMA) stenosis were previously described and both were treated surgically. However, for interventional treatment, securing a sufficient blood supply to the SMA should be a priority of treatment. We present the case of a 71-year-old male with a 20 mm diameter pancreaticoduodenal arterial aneurysm accompanied by SMA stenosis at its origin. The guidewire traverse from SMA to the aneurysm was difficult because of the tight SMA stenosis; however, the guidewire traverse from the celiac artery was finally successful and was followed by balloon angioplasty using a pull-through technique, leading to stent placement. Thereafter, coil packing through the SMA achieved eradication of the aneurysm without bowel ischemia. At the last follow-up computed tomography 8 mo later, no recurrence of the aneurysm was confirmed. The pull-through technique was useful for angioplasty for tight SMA stenosis in this case.

- Citation: Ikoma A, Nakai M, Sato M, Kawai N, Tanaka T, Sanda H, Nakata K, Minamiguchi H, Sonomura T. Inferior pancreaticoduodenal artery aneurysm treated with coil packing and stent placement. World J Radiol 2012; 4(8): 387-390

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1949-8470/full/v4/i8/387.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4329/wjr.v4.i8.387

Of the different types of systemic aneurysm, a visceral aneurysm is rare and occurs with a frequency of 0.1%-0.2%[1]. Splenic artery aneurysm accounts for more than half of all visceral aneurysms, followed by hepatic artery aneurysm, superior mesenteric artery (SMA) aneurysm, celiac artery aneurysm, and pancreaticoduodenal artery aneurysm, with frequencies of 20%, 8%, 4% and 2%, respectively[2]. “ A pancreaticoduodenal artery aneurysm is often accompanied by celiac artery axis stenosis but it is rare for it to occur with SMA stenosis[3,4]. Embolization of a pancreaticoduodenal artery aneurysm under SMA stenosis might induce ischemia to the bowel. Then, before embolization, it is crucial to secure sufficient blood flow of SMA.

We present a case of pancreaticoduodenal artery aneurysm accompanied by a SMA stenosis treated with coil embolization following stent placement using a pull-through technique.

A 71-year-old male presented to our hospital suffering from colon cancer. The patient had no symptoms and laboratory tests revealed no abnormal findings except elevated carcinoembryonic antigen of 6.5 ng/mL. Abdominal computed tomography (CT) using contrast medium for investigating metastases accidentally revealed visceral artery aneurysm of 2 cm in diameter from a branch of the SMA, namely the inferior panncreaticoduodenal artery. Further, it revealed overt stenosis of SMA at its origin (Figure 1). No celiac artery stenosis with median arcuate ligament thickening was observed. After the patient was informed of surgical and intravascular treatments from a team of surgeons and interventional radiologists, he gave consent for treatment with transcatheter arterial embolization (TAE).

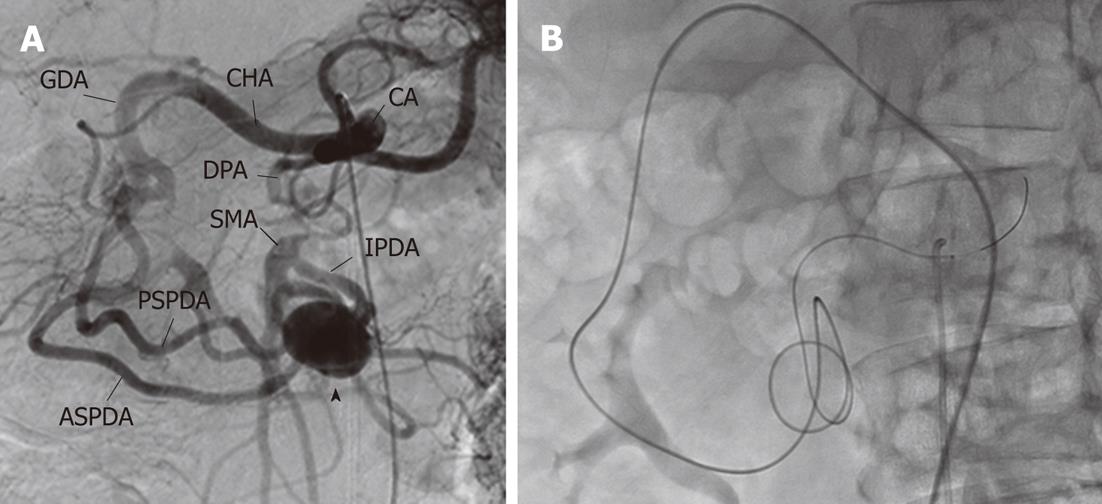

The celiac artery was catheterized using a 4 Fr RC2 (Rosch celiac, Medikit, Tokyo, Japan) through 6 Fr sheath (SuperSheath, Medikit) inserted from the right femoral artery. Celiac arteriography revealed that blood flow from the SMA came from the celiac artery via dilated communications from posterior and anterior superior pancreaticoduodenal arteries to the inferior pancreaticoduodenal artery (IPDA), and an aneurysm was observed at the communication site among the three arteries (Figure 2A). Ischemia to the small intestine should be avoided during embolization so we devised a treatment strategy to dilate the origin of the SMA with stent placement followed by embolization of the aneurysm.

First, the 4 Fr RC2 catheter was withdrawn, a 6 Fr guiding catheter (Envoy, Cordis, Johnson and Johnson, Miami, FL) was inserted from the 6 Fr sheath and the 4 Fr RC2 catheter was reinserted through the guiding catheter to catheterize to the SMA inlet. However, direct catheterization to the SMA was difficult, probably because of tight stenosis.

Then a 4 Fr sheath (SuperSheath, Medikit) was inserted from the left femoral artery and a 4 Fr RC2 catheter was advanced through the sheath to the gastroduodenal artery via the celiac artery and common hepatic artery using a guidewire (0.035, Radiofocus, Terumo, Tokyo, Japan). A 2.2 Fr microcatheter (Shirabe, Piolax, Yokohama, Japan) was inserted through the 4 Fr RC2 catheter and advanced to prior to the origin of SMA over the ASPD and the aneurysm using a microwire (GT, 0.016 inch, 180 cm in length, Terumo). The traverse of the microwire from the SMA origin to aorta was also very tough but finally successful (Figure 2B).

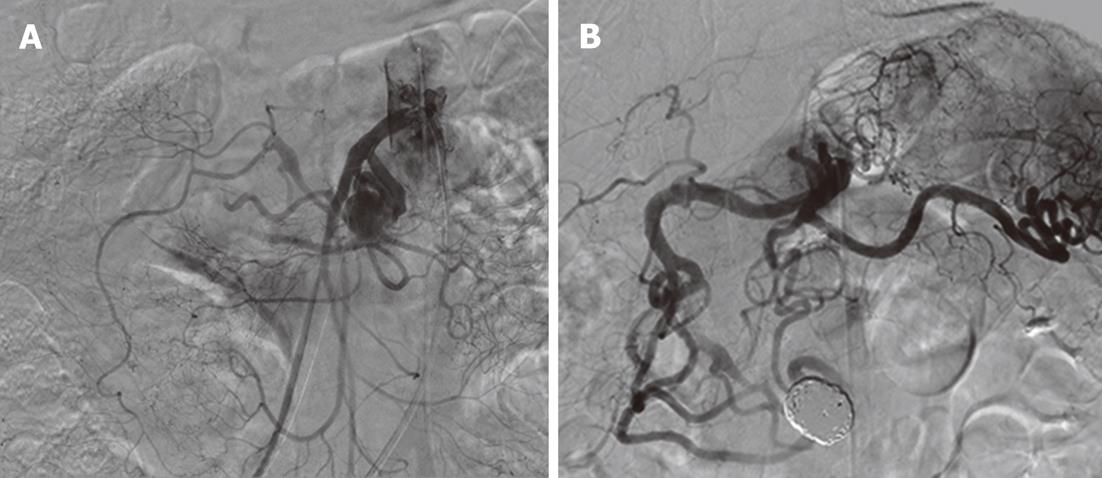

Thereafter, a 4 Fr Amplatz Goose neck snare catheter (EV3 Endovascular Inc., Plymoth, MN) was inserted through the guiding catheter and grasped the microwire in the aorta. The microwire was pulled into the guiding catheter and taken out from the right femoral sheath. Then the pull-through from the left femoral artery to the right femoral artery was completed via the celiac artery, pancreaticoduodenal arcade, aneurysm and superior mesenteric artery. Percutaneous transluminal angioplasty (PTA) for SMA stenosis at its origin was performed using a balloon catheter (Sterling, 4 mm in diameter and 2 cm in length, Boston Scientific, Natic, MA) from a right femoral approach under a pull-through guidewire tension. After balloon dilatation, the 6 Fr guiding catheter was re-inserted and advanced to the SMA over its origin. A balloon expandable stent device (6 Fr, Palmatz Genesis Stent, 5 mm in diameter, 18 mm in length) was inserted to the SMA origin over the micro-guidewire (0.014 inch microwire (Deja-vu, 0.014, 180 cm, Cordis, Endovascular/Johnson and Johnson, Waren, NJ) and the stent was deployed by balloon inflation at 10 atmospheric pressure. Superior mesenteric arteriography after the stent placement revealed the marked dilatation of the SMA at its origin (Figure 3A).

The microcatheter and RC2 catheter were inserted into the guiding catheter and advanced to the aneurysm. After stent deployment, test injection from a microcatheter showed the stagnation of blood flow of anterior and posterior superior pancreaticoduodenal arteries (ASPDA and PSPDA). Taking into consideration that embolizations of ASPDA, PSPDA and IPDA for the isolation of the aneurysm were troublesome and might cause ischemic damage to the small intestine or the duodenum, we attempted to perform selective embolization of aneurysm with microcoils (packing). A microcatheter was placed in the aneurysm using the microwire. The aneurysm was finally packed with 11 guglielmi detachable coils (3; 20 mm in diameter 33 cm in length, 3; 18 mm in diameter 30 cm in length, 3; 16 mm in diameter 30 cm in length, 1; 15 mm in diameter 30 cm in length, 1; 14 mm in diameter 30 cm in length). Celiac arteriography revealed the eradication of the aneurysm (Figure 3B).

The following day, no abnormal symptoms and laboratory test results were observed except slight fever and the mild elevation of c-reactive protein. At the last follow-up, 8 mo later, CT angiography revealed no recurrent stenosis of SMA and no increase in the aneurysm.

Once the peripancreatic artery aneurysm has been found, early eradication is reported to be crucial because the correlation between the size of the peripancreatic artery aneurysm and the incidence of the rupture is not assured[5]. Causes of pancreaticoduodenal artery aneurysm include infection, trauma, pancreatitis, collagen disease and iatrogenic procedures[6]. However, hemodynamic stress accompanied with occlusion or stenosis of the main trunk artery is reported to be the leading cause[6]. Namely, more than half of peripancreatic artery aneurysms are caused by celiac axis stenosis due to a median arcuate ligament thickening[6-8].

Our case had no past history of pancreatitis, infection and collagen disease. As occlusion of the SMA was observed, the cause of the present pancreaticoduodenal artery is considered to be an increase of blood flow from the celiac artery to the SMA via anterior and posterior pancreaticoduodenal arteries[4]. The cause of SMA occlusion was not clarified in this case. To the best of our knowledge, two cases with a pancreaticoduodenal artery aneurysm with SMA stenosis were previously reported with no description about the causes and both of them were treated by surgical repair (aneurysm resection or bypass operation)[3,4].

As the treatment for visceral artery aneurysms, TAE is supplied as a safe and less invasive treatment[7-9]. Isolation[7] and packing[8] using microcoils are suggested as embolization procedures. However, TAE-unmanageable cases exist because of the difficulty of catheterization to the responsible artery, the complicated anastomosis or branching[9]. Further, we have to take into consideration the issue of aneurysm rupture during catheterization or ischemia to visceral organs following embolization in advance[9].

TAE has not been used for treatment of pancreaticoduodenal artery aneurysm accompanied with SMA stenosis before, probably because of the anticipation of bowel ischemia following embolization and difficult catheterization. In our case, the SMA occlusion was too tight to recanalize by catheterization from the SMA origin. However, catheterization from the celiac artery via the pancreaticoduodenal arcade and SMA enabled the traverse of the tight occlusion of SMA origin to the abdominal aorta. A pull-through technique from the left femoral artery to the right femoral artery via the celiac artery, pancreaticoduodenal arcade, aneurysm and superior mesenteric artery enabled balloon PTA, leading to stent placement. Previously, there was one report of successful port-catheter implantation of celiac stenosis using a pull-through technique from the femoral artery to the subclavian artery via the SMA, pancreaticoduodenal arcade and celiac axis artery[10]. When tight occlusion at the celiac axis artery or SMA exists, catheterization using a pull-through technique is considered to be an alternative procedure.

In conclusion, we presented a rare case with pancreaticoduodenal artery aneurysm accompanied by SMA occlusion treated by coil packing to the aneurysm following securing SMA blood flow with stent placement at the SMA origin. A pull-through technique was useful for a possible recanalization for tight SMA occlusion and a balloon PTA.

Peer reviewer: Stefania Romano, MD, Department of Diagnostic Imaging, Section of General and Emergency Radiology, Cardarelli Hospital, Viale Cardarelli, 9, 80131 Naples, Italy

S- Editor Cheng JX L- Editor O’Neill M E- Editor Xiong L

| 1. | Drescher R, Köster O, von Rothenburg T. Superior mesenteric artery aneurysm stent graft. Abdom Imaging. 2006;31:113-116. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Upchurch GR Jr, Zelenock GB, Stanley JC. Splanchnic artery aneurysms. Vascular Surgery, 6th ed. Philadelphia, New York: WB Saunders 2005; 1565-1581. |

| 3. | Ichinokawa M, Iwai K, Matsumura Y, Mega S, Kawasaki R, Takahashi T, Kondo S. [A case of the anterior superior pancreaticoduodenal artery aneurysm with complete occulusion of the superior mesenteric artery]. Jpn J Gastroenterol Surg. 2006;39:1678-1682. |

| 4. | Kimura C, Adachi H, Yamaguchi A, Ino T. A case of an unruptured inferior pancreaticoduodenal artery aneurysm with celiac artery occulusion and superior mesenteric artery stenosis. Jpn J Vasc Surg. 2009;18:691-694. |

| 5. | Moore E, Matthews MR, Minion DJ, Quick R, Schwarcz TH, Loh FK, Endean ED. Surgical management of peripancreatic arterial aneurysms. J Vasc Surg. 2004;40:247-253. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 72] [Cited by in RCA: 79] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Ducasse E, Roy F, Chevalier J, Massouille D, Smith M, Speziale F, Fiorani P, Puppinck P. Aneurysm of the pancreaticoduodenal arteries with a celiac trunk lesion: current management. J Vasc Surg. 2004;39:906-911. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 75] [Cited by in RCA: 83] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Ogino H, Sato Y, Banno T, Arakawa T, Hara M. Embolization in a patient with ruptured anterior inferior pancreaticoduodenal arterial aneurysm with median arcuate ligament syndrome. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol. 2002;25:318-319. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Ikeda O, Tamura Y, Nakasone Y, Kawanaka K, Yamashita Y. Coil embolization of pancreaticoduodenal artery aneurysms associated with celiac artery stenosis: report of three cases. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol. 2007;30:504-507. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Guijt M, van Delden OM, Koedam NA, van Keulen E, Reekers JA. Rupture of true aneurysms of the pancreaticoduodenal arcade: treatment with transcatheter arterial embolization. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol. 2004;27:166-168. [PubMed] |

| 10. | Yamagami T, Kato T, Hirota T, Yoshimatsu R, Matsumoto T, Nishimura T. Use of a pull-through technique at the time of port-catheter implantation in cases of celiac arterial stenosis. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2006;17:1839-1844. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |