Published online Jun 28, 2012. doi: 10.4329/wjr.v4.i6.286

Revised: April 4, 2012

Accepted: April 11, 2012

Published online: June 28, 2012

Papillary thyroid carcinoma with metastasis to the skull is extremely rare. We report a case of unsuspected papillary thyroid carcinoma with skull metastasis. A 48-year-old female patient presenting with painless, pulsatile, progressively increasing swelling in the occipitoparietal region of the scalp approached for an X-ray of the skull. Ultrasound of palpable swelling in the neck revealed a heteroechoic lesion with increased vascularity. Foci of calcification were seen involving both lobes of the thyroid. Ultrasound of scalp showed a destructive mass in the skull with increased vascularity. Biopsy of thyroid lesions revealed branching papillae having a dense fibrovascular core covered by cuboidal epithelial cells with nuclei having a clear ground glass appearance. This case illustrates how isolated extensive skull metastasis can be found in papillary carcinoma patients without causing significant morbidity. Therefore, in the clinical course of thyroid papillary carcinoma, skull metastasis should be considered, and the patients should be meticulously investigated and followed up.

- Citation: Nigam A, Singh AK, Singh SK, Singh N. Skull metastasis in papillary carcinoma of thyroid: A case report. World J Radiol 2012; 4(6): 286-290

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1949-8470/full/v4/i6/286.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4329/wjr.v4.i6.286

Thyroid cancers are quite rare, accounting for only 1.5% of all cancers in adults and 3% of all cancers in children, but the rate of new cases has been increasing in the last decades[1]. The highest incidence of thyroid carcinomas in the world is found among female Chinese residents of Hawaii. During the last few years, the frequency of papillary cancer has increased, but this increase in frequency is related to an improvement in diagnostic techniques and the information campaign about this carcinoma. Of all thyroid cancers, 74%-80% of cases are papillary cancer.

Papillary carcinoma is a relatively common well-differentiated thyroid cancer. Papillary carcinoma may be considered a variant of mixed form thyroid carcinoma. Despite its well-differentiated characteristics, papillary carcinoma may be overtly or minimally invasive[2]. In fact, these tumors may spread easily to other organs. Papillary tumors have a propensity to invade lymphatics but are less likely to invade blood vessels[3]. Papillary carcinoma typically arises as an irregular, solid or cystic mass that arises from otherwise normal thyroid tissue. Thyroid cancers are more often found in patients with a history of low- or high-dose external irradiation[4]. Papillary tumors of the thyroid are the most common form of thyroid cancer to result from exposure to radiation. The life expectancy of patients with this cancer is related to their age[5-7].

Bone is the only site of distant metastasis in about 1.7% of patients with differentiated thyroid carcinoma[8], and the 5-year cause-specific survival for those with papillary carcinoma is about 10%[9]. Skeletal deposits of neoplasm pose special hazards of fracture and, when adjacent to the central nervous system, neurologic impairment. In addition, stimulation by thyrotropin may produce swelling of metastases and abrupt clinical deterioration.

Skull metastasis of extracranial origin is rare. The most common forms are pulmonary, breast and prostate carcinomas[10]. Metastasis in the skull associated with carcinoma of the thyroid accounts for only 2.5%-5.8% of cases, but the initial presentation with distant metastasis is uncommon[11]. Isolated forms have radiological features that strongly suggest a primary tumor, and furthermore, their macroscopic appearance during surgery may even be taken for a meningioma[12]. In this paper, we illustrate how isolated extensive skull metastasis can be found in papillary carcinoma patients without causing significant morbidity.

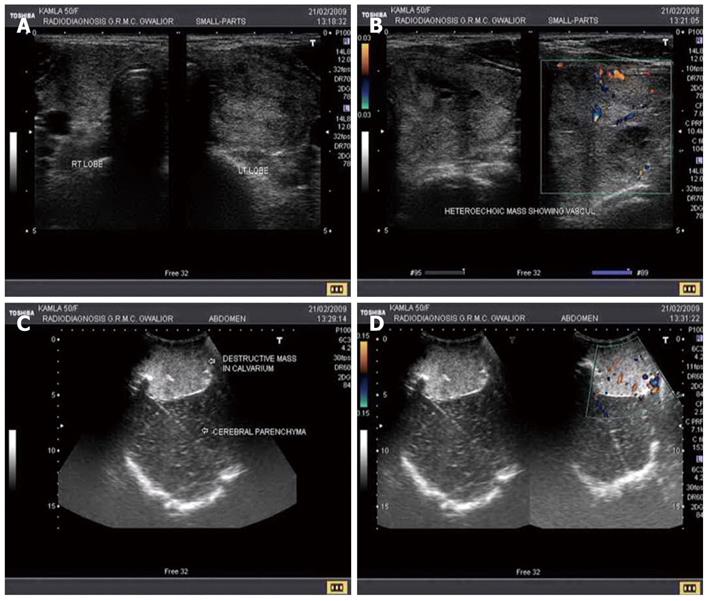

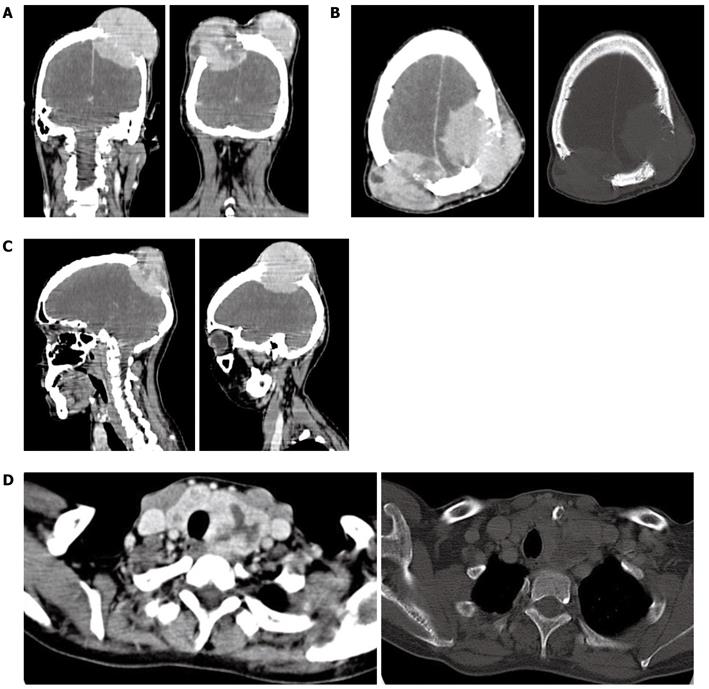

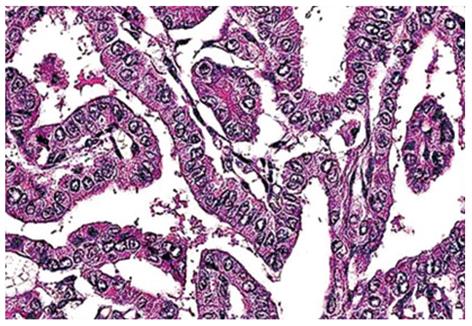

A 48-year-old female presented to the Department of Radiodiagnosis, Jaya Arogya Group of Hospitals, Gwalior, India, with a couple of painless, progressively increasing swellings in the occipitoparietal region of the scalp; she presented to us for an X-ray of the skull (Figure 1). An ultrasound performed for palpable swelling in the neck revealed a heteroechoic lesion with increased vascularity and foci of calcification seen involving both lobes of the thyroid (left and right) (Figure 2A and B). Ultrasound of scalp showed a destructive mass in the skull with increased vascularity (Figure 2C and D). Chest X-ray and ultrasound of the abdomen were normal. Computed tomography (CT) of the head revealed a defect in the calvarium with a soft tissue density lesion having both intra- as well as extracranial soft tissue components (Figure 3A-C). CT of the neck showed a large mass involving the whole of the neck, trachea and vessels (Figure 3D). The histopathological report of a biopsy from the thyroid lesion revealed branching papillae having a dense fibrovascular core covered by cuboidal epithelial cells that contained nuclei having a clear ground glass appearance (Figure 4).

Apart from mild constitutional symptoms, detailed history revealed no significant complaints. There was no significant past history of radiation exposure or family history of thyroid cancer. On examination, the patient had a mild pallor. Two firm, immobile and pulsatile swellings in the occipitoparietal region of the scalp had approximate sizes of 8 cm × 6 cm on the left side and 4 cm × 3 cm on the right side. There was no evidence of any other swellings in the body. Systemic examination was unremarkable. Lab investigation showed decreased hemoglobin (8.2 gm%); the rest of the hemogram was within normal range. Peripheral smear of RBCs was microcytic hypochromic. LFT, RFT, thyroid function test and coagulation studies were within normal range.

Thyroid carcinoma accounts for 1% of all thyroid tumors[1]. Bone metastasis occurs in 10% to 40%, with skull metastasis accounting for 2.5% to 5.8% of bone metastasis. Papillary carcinoma of thyroid is the most common type of thyroid cancer, accounting for 70%-90% of well differentiated thyroid malignancies.

Papillary thyroid carcinomas are subtypes of thyroid cancers which are slow growing tumors and are associated with a favorable prognosis except when they present with distant metastasis[13]. Lung and bone are the two most favored sites of metastasis[14]. Bone metastases from papillary thyroid carcinomas tend to be multiple and more often to the ribs, vertebrae and sternum[15]. Skull is a rare site for metastases, which when they occur, are most commonly located in the occipital region presenting as a soft, painless lump[1,16]. These lesions are osteolytic on skull X-ray and CT scan and highly vascular on angiographic assessment[1,17]. Prognosis in the case of metastasis is generally poor and the 10-year survival with bone metastasis from differentiated thyroid cancers is reported to be 27%[2]. Since the presence of bone metastasis markedly worsens the prognosis, early detection is important. The mean period from the initial diagnosis of thyroid papillary carcinoma until the detection of skull metastasis is 23.3 years[4], whereas in our case both were diagnosed simultaneously. Therefore detection of skull metastasis should be considered in all cases of papillary carcinoma as early as possible. In this study, radioiodine imaging was not performed because papillary carcinoma had already been confirmed by CT scan/ultrasound of the neck and biopsy of the thyroid nodule. The patient’s tumor had already metastasized to the brain so there was no indication/justification for using radioiodine scan. Therefore, this was not advised for this patient. After broad discussion in a tumor board meeting, the following treatment is planned: firstly, three cycles of chemotherapy are given to the patient. The regime is injection of carboplatin 450 mg on day one, injection of doxorubicin 50 mg on day one, and injection of zoledronic acid 4 mg on day two. After completion of 3 cycles of chemotherapy, the patient is subjected to whole brain radiotherapy 10 Gy in 10 fractions over 2 wk. After completing the radiotherapy, the patient is again subjected to 3 cycles of chemotherapy in the same regime.

This case illustrates how isolated, extensive skull metastasis can be found in patients with papillary carcinoma without causing significant morbidity. Therefore, in the clinical course of thyroid papillary carcinoma, skull metastasis should be considered and patients should be meticulously investigated and followed up.

Peer reviewer: Martin A Walter, MD, Institute of Nuclear Medicine, University Hospital, Petersgraben 41, CH-4031 Basel, Switzerland

S- Editor Cheng JX L- Editor Logan S E- Editor Zheng XM

| 1. | Nagamine Y, Suzuki J, Katakura R, Yoshimoto T, Matoba N, Takaya K. Skull metastasis of thyroid carcinoma. Study of 12 cases. J Neurosurg. 1985;63:526-531. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 58] [Cited by in RCA: 62] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Wada N, Sugino K, Mimura T, Nagahama M, Kitagawa W, Shibuya H, Ohkuwa K, Nakayama H, Hirakawa S, Yukawa N. Treatment strategy of papillary thyroid carcinoma in children and adolescents: clinical significance of the initial nodal manifestation. Ann Surg Oncol. 2009;16:3442-3449. [PubMed] |

| 3. | Clayman GL, Shellenberger TD, Ginsberg LE, Edeiken BS, El-Naggar AK, Sellin RV, Waguespack SG, Roberts DB, Mishra A, Sherman SI. Approach and safety of comprehensive central compartment dissection in patients with recurrent papillary thyroid carcinoma. Head Neck. 2009;31:1152-1163. [PubMed] |

| 4. | Rosenbaum MA, McHenry CR. Contemporary management of papillary carcinoma of the thyroid gland. Expert Rev Anticancer Ther. 2009;9:317-329. [PubMed] |

| 5. | Pelizzo MR, Merante Boschin I, Toniato A, Pagetta C, Casal Ide E, Mian C, Rubello D. Diagnosis, treatment, prognostic factors and long-term outcome in papillary thyroid carcinoma. Minerva Endocrinol. 2008;33:359-379. [PubMed] |

| 6. | Thyroid Carcinoma Task Force. AACE/AAES Medical/Surgical Guidelines for Clinical Practice: Management of Thyroid Carcinoma. Accessed December 16, 2009. AACE Guidelines. Available from: http://www.aace.com/pub/pdf/guidelines/thyroid_carcinoma.pdf. |

| 7. | National Comprehensive Cancer Network Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology. Thyroid carcinoma. National Comprehensive Cancer Network. Available from: www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/PDF/thyroid.pdf. |

| 8. | Ruegemer JJ, Hay ID, Bergstralh EJ, Ryan JJ, Offord KP, Gorman CA. Distant metastases in differentiated thyroid carcinoma: a multivariate analysis of prognostic variables. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1988;67:501-508. [PubMed] |

| 9. | Dinneen SF, Valimaki MJ, Bergstralh EJ, Goellner JR, Gorman CA, Hay ID. Distant metastases in papillary thyroid carcinoma: 100 cases observed at one institution during 5 decades. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1995;80:2041-2045. [PubMed] |

| 11. | Turner O, German WJ. Metastases in the skull from carcinoma of the thyroid. Surgery. 1941;9:403-414. |

| 12. | Tagle P, Villanueva P, Torrealba G, Huete I. Intracranial metastasis or meningioma? An uncommon clinical diagnostic dilemma. Surg Neurol. 2002;58:241-245. [PubMed] |

| 13. | Cobin RH, Gharib H, Bergman DA, Clark OH, Cooper DS, Daniels GH, Dickey RA, Duick DS, Garber JR, Hay ID. AACE/AAES medical/surgical guidelines for clinical practice: management of thyroid carcinoma. American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists. American College of Endocrinology. Endocr Pract. 2001;7:202-220. [PubMed] |

| 14. | Schlumberger M, Tubiana M, De Vathaire F, Hill C, Gardet P, Travagli JP, Fragu P, Lumbroso J, Caillou B, Parmentier C. Long-term results of treatment of 283 patients with lung and bone metastases from differentiated thyroid carcinoma. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1986;63:960-967. [PubMed] |

| 15. | Zettinig G, Fueger BJ, Passler C, Kaserer K, Pirich C, Dudczak R, Niederle B. Long-term follow-up of patients with bone metastases from differentiated thyroid carcinoma -- surgery or conventional therapy? Clin Endocrinol (Oxf). 2002;56:377-382. [PubMed] |

| 16. | Inci S, Akbay A, Bertan V, Gedikoğlu G, Onol B. Solitary skull metastasis from occult thyroid carcinoma. J Neurosurg Sci. 1994;38:63-66. [PubMed] |

| 17. | Akdemir I, Erol FS, Akpolat N, Ozveren MF, Akfirat M, Yahsi S. Skull metastasis from thyroid follicular carcinoma with difficult diagnosis of the primary lesion. Neurol Med Chir (Tokyo). 2005;45:205-208. [PubMed] |