Published online Jun 28, 2012. doi: 10.4329/wjr.v4.i6.253

Revised: April 25, 2012

Accepted: May 2, 2012

Published online: June 28, 2012

The prevalence of chronic kidney disease and peripheral arterial disease is increasing. Thus, it is increasingly problematic to image these patients as the number of patients needing a vascular examination is increasing accordingly. In high-risk patients with impaired kidney function, intravascular administration of iodinated contrast media can result in contrast-induced acute kidney injury and Gadolinium can induce nephrogenic systemic fibrosis (NSF). It is important to identify these high-risk patients by means of se-creatinine/e glomerular filtration rate. The indication for contrast examination should counterbalance the increased risk. One or more alternative examination methods without contrast media, such as CO2 angiography, Ultrasound/Doppler examination or magnetic resonance angiography without contrast should be considered, but at the same time, allow for a meaningful outcome of the examination. If contrast is deemed essential, the patient should be well hydrated, the amount of contrast should be restricted, the examination should be focused, metformin and diuretics stopped, and renal function monitored. Sodium bicarbonate and N-acetylcysteine are popular but their efficiency is not evidence-based. There is no evidence that dialysis protects patients with impaired renal function from contrast-induced nephropathy or NSF.

- Citation: Andersen PE. Patient selection and preparation strategies for the use of contrast material in patients with chronic kidney disease. World J Radiol 2012; 4(6): 253-257

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1949-8470/full/v4/i6/253.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4329/wjr.v4.i6.253

Before any kind of intervention, it is essential to have a good clinical history and examination of patients. The indications for interventional treatment should always be explained, and patients should have consented to interventional treatment before initiating imaging which could be potentially kidney damaging. The situation with patients who refuse interventional treatment after angiography because their symptoms have resolved or are too vague is well known, and should be avoided. The risk of complications/side effects of the interventional treatment should be lower than the medical treatment or spontaneous course of the disease in the short- and long-term. When the indication to treat is defined, it is necessary to have a “map” of the target lesion to evaluate the location, the nature of the lesion, the severity, extension, run-in and -off, and to evaluate the access route to the lesion. This is the case in all patients, both with normal as well as impaired kidney function. In general, it is not good clinical practice to treat accidentally found non-symptomatic vascular lesions without consequences to the patient, and only restrict the interventions to symptomatic lesions. It is the patients’ symptoms and not the pictures that should be treated. The wide and easy access to very fast and sensitive non- or minimally-invasive diagnostic modalities has resulted in extensive use of these modalities for a wide range of indications, and often patients will have been examined with two or more modalities when only one is needed for diagnostic purposes before intervention. Digital subtraction angiography (DSA) is still the gold standard and can be followed immediately by intervention, sparing the patients an extra arterial puncture and visit to the hospital. However, computed tomography (CT) angiography and magnetic resonance (MR) angiography are replacing DSA in most institutions.

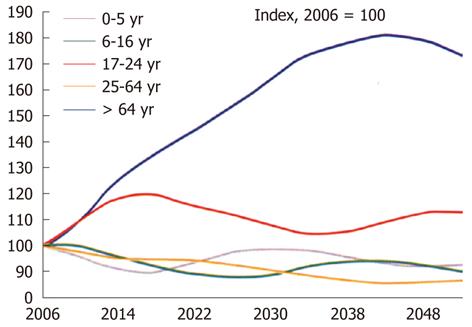

The prevalence of chronic kidney disease (CKD)[1-3] (Table 1) and peripheral arterial disease (PAD)[4-7] (Table 2) has increased significantly during the last decades. This is explained by the number of people suffering from diabetes, and the prevalence of diabetes is rising at an alarming speed. According to the World Health Organization, the number of patients with diabetes will be pandemic by 2025 and the number will double by 2030. Most of these patients will die or be disabled by vascular complications. Furthermore, there is an increasing prevalence of hypertension as well as increasing age of the population (Figure 1) and higher body mass index. The prevalence of PAD significantly increases with age, diabetes, CKD, smoking, and hypertension[8-10]. Thus, it is increasingly problematic to image patients with both PAD and CKD as the number of patients with CKD who need a vascular examination is increasing. Therefore, it is a challenge to image these patients. Intravascular administration of iodinated contrast media can result in contrast-induced acute kidney injury (formerly CIN) and gadolinium can induce nephrogenic systemic fibrosis (NSF) in high-risk patients. However, the overall incidence of CIN after iso-osmolar contrast-enhanced CT seems to be low - about 3% and is about 5% in patients with CKD.

| 1988-1994 | 1999-2004 | ||

| Stage 1 | (persistent albuminuria + normal GFR) | 1.7% | 1.8% |

| Stage 2 | (persistent albuminuria + GFR 60-89) | 2.7% | 3.2% |

| Stage 3 | (GFR 30-59) | 5.4% | 7.7% |

| Stage 4 | (GFR 15-29) | 0.2% | 0.4% |

| Stage 5 | (kidney failure) 0.2% | ||

| Total | 10.0% | 13.1% |

| Increased in diabetes (relative risk increase for PAD > 4.0; 20%-30% have PAD) |

| Increases significantly with age (40-49 yr 1% → >80 yr 22% equal to doubling each decade) |

| Increases in CKD |

| Increases in smoking (2.5), hypertension (1.5), dyslipidemia (1.1), high body mass index, black race |

| In the U.S. population > 40 yr 4.5% (corresponds to 12 mill) have PAD (AB index < 0.9%) (NHANES), > 60 yr over 10% |

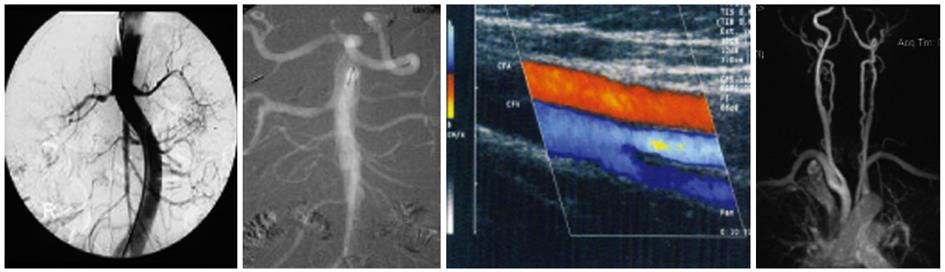

The primary risk factor for contrast media-induced nephrotoxicity is pre-existing renal dysfunction, especially diabetic nephropathy (Figure 2). In general, it is important to identify high-risk patients and the determination of se-creatinine/estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR), especially in patients with known diabetes and suspected or known reduced kidney function, is mandatory and should be available before all intravascular examinations with iodinated contrast media or gadolinium. It is quick and easy to perform on-site creatinine/eGFR measurements in the Radiologic Department using a small portable monitor. If the patient is high-risk, the indication for use of contrast media should be reconsidered. Does the indication counterbalance the increased risk? Alternative examinations not using iodinated contrast or gadolinium should be considered, and at the same time allow for a meaningful outcome. The amount of contrast should always be restricted consistent with a diagnostic result. The patients should always be well hydrated and low- or iso-osmolar contrast media should be used[11].

Overlooking a severe disease is also an important factor that should be considered when choosing an examination method without the use of a conventional contrast medium.

If the indication for contrast examination counterbalances the increased risk, nephrotoxic drugs, mannitol and loop diuretics should be stopped at least 24 h before contrast medium administration. Hydration of the patient should be started (e.g., 1 mL/kg b.w. per hour of normal saline for at least 6 h before the examination and the patient should continue to drink freely.

In patients with GFR < 60 mL/min per 1.73 m2 the following should be considered: (1) Alternative imaging modalities not using iodinated contrast media or gadolinium, such as e.g., CO2 angiography, duplex US, CT- or MR angiography without contrast, intravascular US, PET/SPECT-CT or scintigraphy. All contrast media used in CTA/DSA/MRA examinations can be removed by dialysis, but there is no evidence that dialysis protects patients with impaired renal function from contrast-induced nephropathy or NSF. MR-guided intervention or image fusion-based 3D navigation are options in some Institutions; (2) In examinations using iodine contrast, patients should be well hydrated; (3) Interrupt diuretics if possible; (4) Only a limited recommendation can be made in favour of the use of sodium bicarbonate based on reviews and a meta-analysis[12]. If it has been decided to give sodium bicarbonate then start with 1.4% - 3 mL/kg per hour 1 h before examination and continue with 1 mL/kg per hour during and 6 h after examination; (5) The use of N-acetylcysteine is popular, has low risk, and gives the impression of “doing something”, but its efficiency is not evidence-based[13]. If it has been decided to give N-acetylcysteine then start with 600 mg po twice daily the day before the examination and during the day of examination; and (6) B-type natriuretic peptide seems to promote the recovery of renal function and decreases the occurrence of contrast-induced nephropathy as compared with routine treatment alone in patients with heart failure undergoing primary percutaneous coronary intervention[14], but further studies are needed to support this.

Diabetic patients taking metformin with 30 < eGFR < 60 mL/min per 1.73 m2 should stop metformin 48 h before the examination using iodinated contrast media and restart only if se-creatinine is unchanged 48 h after the examination. If eGFR is < 30 mL/min per 1.73 m2, metformin is not approved and contrast medium should be avoided.

Gadolinium-containing contrast is now considered contraindicated in patients with a GFR < 60 mL/min, especially in those with GFR < 30 mL/min due to the risk of developing NSF.

In patients at increased risk of nephrotoxicity the following should be considered: (1) Weigh the risk and benefits of contrast administration. Consider an alternative imaging modality not using iodinated contrast media or gadolinium; and (2) In examinations with iodine contrast, start i.v. hydration as early as possible before contrast administration (e.g., at least 1 mL/h per kg bw of iv saline up to 6 h after contrast examination). Monitor renal function (GFR/se-creatinine), se-lactic acid, and blood pH until 2 d after the examination. Stop metformin in diabetic patients. “Shoot first, ask later” may be necessary in emergency cases.

In diabetic patients taking metformin with eGFR < 60 mL/min, weigh the risk and benefits of contrast administration and consider an alternative imaging method. If contrast is deemed essential then stop metformin, hydrate the patient, and monitor renal function.

Continue hydration for at least 6 h. In diabetic patients taking metformin eGFR should be measured 48 h after contrast administration. If there is no deterioration in eGFR, metformin can be restarted.

Clinical experience with CO2 as a contrast agent has shown that it is safe, and in patients with CKD can prevent contrast-induced nephropathy. The disadvantages of CO2 are that it requires a unique delivery system and is contraindicated in the cerebral and coronary circulation and thoracic aorta[13] (Figure 2).

Doppler/Duplex ultrasound gives good information on the anatomy and physiology of the vessels examined. 3-D reconstructions are possible. Ultrasound analysis is almost always based on blood flow velocity measurements. This modality is economical, and can be performed in out-patients or at the bed-side. Functional tests can be performed. The drawback is that this method is examiner-dependent and reproducibility is limited (Figure 2).

There is a need for non-contrast MRA, especially in patients with CKD. Non-contrast enhanced MRA techniques have recently been developed and consist of ECG-gated and respiratory-gated balanced steady-state gradient echo acquisitions obtaining arterial contrast by acquiring data at delayed times following the gating trigger. Magnetization preparation pulses are used to allow the systolic in-flow contrast of the arterial blood to dominate. Furthermore, techniques of phase-contrast angiography and time-of-flight angiography have been developed. These techniques can be used to answer specific clinical questions, such as the presence of occlusive diseases in renal and carotid arteries[15]. The limitations are that this modality is expensive, has limited availability, limited depiction of small vessels, limited use in patients with claustrophobia or with metal/pacemaker in the body and possibly overestimates stenoses (Figure 2).

NSF is fibrosis of the skin, joints, eyes, and internal organs and appears in various stages from death and nearly complete disability to small plaques on the skin (Figure 3). It is associated with exposure to gadolinium in patients with severe kidney failure. The first cases were found in 1997, but the link was not identified until 2006. NSF develops in a dose-and time-dependent manner[13,16]. The risk of NSF development after exposure to gadolinium-based contrast agents is about 1%-4% in patients who undergo haemodialysis or renal transplantation[17]. NSF has not been described in patients undergoing a single examination with stable macrocyclic gadolinium, whereas multiple cases have been reported after exposure to less stable agents. There seems to be a difference in the prevalence between ionic and non-ionic linear chelates with a prevalence of around 5%-6% for non-ionic linear agents. It seems that enhanced MRI with a low-risk NSF agent is safer for a patient with severe CKD than an enhanced CT with a non-ionic agent but no evidence is available. In patients with zero urine production, enhanced CT seems to be safer if it is diagnostically superior to MRI[18,19]. MR contrast in CKD patients should only be given when the indication is urgent and if the same information cannot be achieved without MR contrast or using other imaging modalities. Otherwise, non-contrast-based techniques should be used. If contrast is deemed essential the dose should be minimized, and MR scanning not repeated with contrast. A test bolus should be avoided and low-risk (macrocyclic) contrast used (Table 3). Gadolinium-containing contrast is now considered contraindicated in patients with GFR < 60 mL/min, especially in patients with GFR < 30 mL/min due to the risk of developing NSF.

| Risk | GFR < 30 | GFR 30-60 | GFR > 60 |

| High - linear (Omniscan, Magnevist, Optimark, Multihance) | Do not use | Urgent indic. | Can be used |

| Low - stable, macrocyclic (Dotarem, Gadovist, Prohance) | Urgent indic. | Can be used | Can be used |

It is essential to identify patients at risk. Consider one or more combined alternative imaging modalities which do not require contrast media. If contrast is deemed essential: hydrate the patient, restrict the amount of contrast (focused examination), use low risk MR contrast, stop metformin, interrupt diuretics, and monitor renal function. The strategy for examining patients with CKD will most often come down to which modalities and methods each person is most used to, has access to, and is comfortable with.

Peer reviewer: Louis R Kavoussi, Dr., Department of Urology, New Hyde Park, 450 Lakeville Road, NY 11042, United States

S- Editor Cheng JX L- Editor Webster JR E- Editor Zheng XM

| 1. | Coresh J, Selvin E, Stevens LA, Manzi J, Kusek JW, Eggers P, Van Lente F, Levey AS. Prevalence of chronic kidney disease in the United States. JAMA. 2007;298:2038-2047. [PubMed] |

| 2. | National Kidney Foundation 2003 Clinical Meetings Abstracts April 2–6, 2003. Am J Kidney Dis. 2003;41:B1-B40. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | McGeown MG. Prevalence of advanced renal failure in Northern Ireland. BMJ. 1990;301:900-903. [PubMed] |

| 4. | Selvin E, Erlinger TP. Prevalence of and risk factors for peripheral arterial disease in the United States: results from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 1999-2000. Circulation. 2004;110:738-743. [PubMed] |

| 5. | Gregg EW, Sorlie P, Paulose-Ram R, Gu Q, Eberhardt MS, Wolz M, Burt V, Curtin L, Engelgau M, Geiss L. Prevalence of lower-extremity disease in the US adult population & gt; =40 years of age with and without diabetes: 1999-2000 national health and nutrition examination survey. Diabetes Care. 2004;27:1591-1597. [PubMed] |

| 7. | Fowkes FG, Housley E, Cawood EH, Macintyre CC, Ruckley CV, Prescott RJ. Edinburgh Artery Study: prevalence of asymptomatic and symptomatic peripheral arterial disease in the general population. Int J Epidemiol. 1991;20:384-392. [PubMed] |

| 8. | Marso SP, Hiatt WR. Peripheral arterial disease in patients with diabetes. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2006;47:921-929. [PubMed] |

| 9. | van Kuijk JP, Flu WJ, Chonchol M, Welten GM, Verhagen HJ, Bax JJ, Poldermans D. The prevalence and prognostic implications of polyvascular atherosclerotic disease in patients with chronic kidney disease. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2010;25:1882-1888. [PubMed] |

| 10. | Selvin E, Köttgen A, Coresh J. Kidney function estimated from serum creatinine and cystatin C and peripheral arterial disease in NHANES 1999-2002. Eur Heart J. 2009;30:1918-1925. [PubMed] |

| 11. | Thomsen HS. European Society of Urogenital Radiology (ESUR) guidelines on contrast media, version 7.0. Heidelberg, Germany: European Society of Urogenital Radiology 2008; . |

| 12. | Hoste EA, De Waele JJ, Gevaert SA, Uchino S, Kellum JA. Sodium bicarbonate for prevention of contrast-induced acute kidney injury: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2010;25:747-758. [PubMed] |

| 13. | Ellis JH, Cohan RH. Prevention of contrast-induced nephropathy: an overview. Radiol Clin North Am. 2009;47:801-811. [PubMed] |

| 14. | Zhang J, Fu X, Jia X, Fan X, Gu X, Li S, Wu W, Fan W, Su J, Hao G. B-type natriuretic peptide for prevention of contrast-induced nephropathy in patients with heart failure undergoing primary percutaneous coronary intervention. Acta Radiol. 2010;51:641-648. [PubMed] |

| 15. | Houston JG, Gandy SJ, Milne W, Dick JB, Belch JJ, Stonebridge PA. Spiral laminar flow in the abdominal aorta: a predictor of renal impairment deterioration in patients with renal artery stenosis? Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2004;19:1786-1791. [PubMed] |

| 16. | Marckmann P, Skov L, Rossen K, Dupont A, Damholt MB, Heaf JG, Thomsen HS. Nephrogenic systemic fibrosis: suspected causative role of gadodiamide used for contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2006;17:2359-2362. [PubMed] |

| 17. | Schlaudecker JD, Bernheisel CR. Gadolinium-associated nephrogenic systemic fibrosis. Am Fam Physician. 2009;80:711-714. [PubMed] |

| 18. | Abujudeh HH, Kaewlai R, Kagan A, Chibnik LB, Nazarian RM, High WA, Kay J. Nephrogenic systemic fibrosis after gadopentetate dimeglumine exposure: case series of 36 patients. Radiology. 2009;253:81-89. [PubMed] |

| 19. | Lind Ramskov K, Thomsen HS. Nephrogenic systemic fibrosis and contrast medium-induced nephropathy: a choice between the devil and the deep blue sea for patients with reduced renal function? Acta Radiol. 2009;50:965-967. [PubMed] |