Published online Nov 28, 2012. doi: 10.4329/wjr.v4.i11.450

Revised: September 23, 2012

Accepted: September 30, 2012

Published online: November 28, 2012

AIM: To clarify the usefulness of arterial phase scans in contrast computed tomography (CT) imaging of strangulation ileus in order to make an early diagnosis.

METHODS: A comparative examination was carried out with respect to the CT value of the intestinal tract wall in each scanning phase, the CT value of the content in the intestinal tract, and the CT value of ascites fluid in the portal vein phase for a group in which ischemia was observed (Group I) and a group in which ischemia was not observed (Group N) based on the pathological findings or intra-surgical findings. Moreover, a comparative examination was carried out in Group I subjects for each scanning phase with respect to average differences in the CT values of the intestinal tract wall where ischemia was suspected and in the intestinal tract wall in non-ischemic areas.

RESULTS: There were 15 subjects in Group I and 30 subjects in Group N. The CT value of the intestinal tract wall was 41.8 ± 11.2 Hounsfield Unit (HU) in Group I and 69.6 ± 18.4 HU in Group N in the arterial phase, with the CT value of the ischemic bowel wall being significantly lower in Group I. In the portal vein phase, the CT value of the ischemic bowel wall was 60.6 ± 14.6 HU in Group I and 80.7 ± 17.7 HU in Group N, with the CT value of the ischemic bowel wall being significantly lower in Group I; however, no significant differences were observed in the equilibrium phase. The CT value of the solution in the intestine was 18.6 ± 9.5 HU in Group I and 10.4 ± 5.1 HU in Group N, being significantly higher in Group I. No significant differences were observed in the CT value of the accumulation of ascites fluid. The average difference in the CT values between the ischemic bowel wall and the non-ischemic bowel wall for each subject in Group I was 33.7 ± 20.1 HU in the arterial phase, being significantly larger compared to the other two phases.

CONCLUSION: This is a retrospective study using a small number of subjects; however, it suggests that there is a possibility that CT scanning in the arterial phase is useful for the early diagnosis of strangulation ileus.

- Citation: Ohira G, Shuto K, Kono T, Tohma T, Gunji H, Narushima K, Imanishi S, Fujishiro T, Tochigi T, Hanaoka T, Miyauchi H, Hanari N, Matsubara H, Yanagawa N. Utility of arterial phase of dynamic CT for detection of intestinal ischemia associated with strangulation ileus. World J Radiol 2012; 4(11): 450-454

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1949-8470/full/v4/i11/450.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4329/wjr.v4.i11.450

Strangulation ileus is an intestinal obstruction associated with ischemia of the intestinal tract which, if left untreated, results in intestinal necrosis and could become fatal if it develops from perforation to peritonitis; therefore, it requires timely treatment[1-5]. If diagnosed before the development of intestinal necrosis and surgery is performed, it is possible to avoid enterectomy by simply releasing the strangulation. If time elapses, it results in intestinal necrosis, leaving no choice but to perform enterectomy, which may cause complications such as ruptured suture and anastomotic stricture.

Regarding early diagnosis of strangulation ileus, there have been a series of reports indicating the usefulness of computed tomography (CT) [6-18]; however, there are few reports discussing the differences in the diagnosability in the scanning phase of CT [17].

We routinely perform dynamic CT in clinical practice for patients who are suspected of having bowel obstruction in order to rule out mesenteric vascular disease such as superior mesenteric arterial thrombosis, which usually develops symptoms similar to those of bowel obstruction. Among our surgical cases of bowel obstruction that needed bowel resection, there were some cases demonstrating hypo-attenuating bowel in the arterial phase that showed an equivalent attenuation in the other phases. We therefore hypothesized that the arterial phase of dynamic CT for patients with bowel obstruction is more useful for the early detection of bowel ischemic change than conventional enhanced CT.

The objective of this study is to retrospectively study pre-surgical contrast CT images of subjects in whom ileus surgery was performed at our department and to clarify the diagnosability according to the scanning phases, particularly the usefulness of arterial phase scans.

Between January 2004 and January 2011, among 139 subjects in whom a laparotomy was carried out based on the diagnosis of an intestinal obstruction at our department, contrast CT scanning (including the arterial phase) was performed prior to surgery in 65 subjects. Among these, it was difficult to evaluate the blood flow of the intestinal tract in a total of 20 subjects, including 11 subjects in whom intestinal tract expansion was not observed after an ileus tube was inserted, 4 subjects in whom it was difficult to evaluate the contrast effect of the intestinal tract after ingestion of the oral contrast agent, and 5 subjects in whom a sufficient amount of contrast agent could not be injected due to their poor general condition. As a result, the remaining 45 subjects were selected as subjects of the study.

These 45 subjects included 31 male subjects and 14 female subjects. The average age was 61.2 years (range: 14-85 years). There were 43 subjects (95.6%) with an intestinal obstruction believed to be caused by the previous laparotomy, and these were composed of: 25 subjects with digestive cancer, 5 subjects with gynecologic cancer, 5 subjects with inflammatory bowel disease, 2 subjects with vascular lesions, and 6 subjects involving other causes. Regarding the two subjects having no previous laparotomy, one subject had an intra-abdominal abscess caused by appendicitis and the intestinal obstruction was caused by adhesions around the abscess. The remaining one subject had an intestinal obstruction caused by ileum invasion of rectal cancer.

Scanning method: All patients were scanned on a 16-multidetector computed tomography (MDCT) (Light Speed Ultra 16, GE Healthcare) and 300 mgI/mL of a non-ionic contrast agent was used, injecting 130 mL to 140 mL at 3-4 mL/s; scanning was carried out in the scanning range from the diaphragm to the pubic symphysis after 30 s in the arterial phase at a slice thickness of 1.25 mm and after 80 s in the portal vein phase. Scanning was performed after 180 s in the equilibrium phase in 27 subjects. The radiation dose of these series ranged from 40 mGy to 80 mGy.

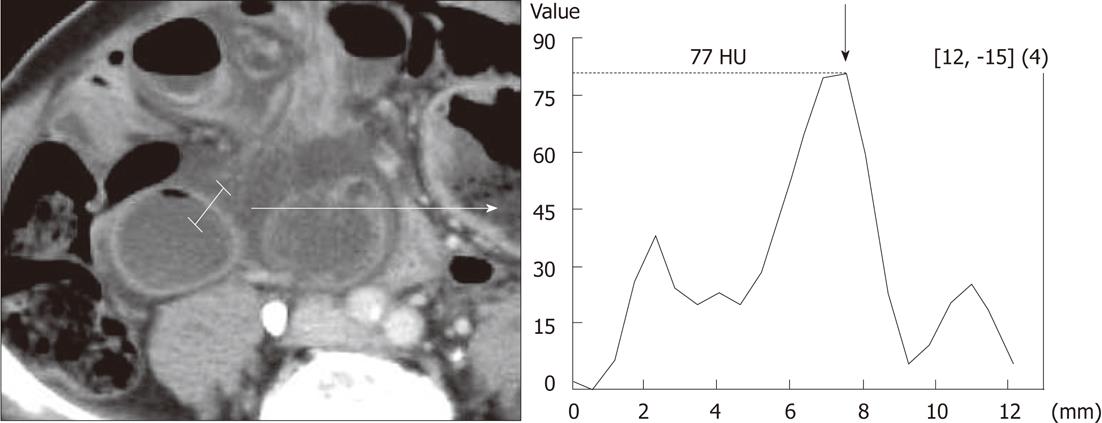

Image analysis method: Sites with no or poor contrast effect or an intestinal tract with a prominent edema were determined based on agreement between two physicians (Ohira G and Tohma T), experienced in abdominal image diagnosis. The CT value of the intestinal tract wall was measured using a MDCT workstation (Advantage Workstation, GE Healthcare, America; Virtual Place Advance, Aze, Tokyo). The measurement method was such that the CT value was continuously measured from the inner side to the outer side of the intestinal tract with poor contrast effect or with high edema and the highest value was set as the CT value of the wall. This method was carried out at any three sites in each scanning phase, and the mean value was calculated (Figure 1). For subjects without poor contrast effect or with no edema, the CT value was measured in the enlarged intestinal tract in a similar manner. Moreover, a circular region of interest was set inside the enlarged intestinal tract in the portal vein phase, the CT value of the fluid inside the enlarged intestinal tract was measured at any three sites, and the mean value was calculated. This method was carried out in a similar manner for cases in which ascites fluid had accumulated, and a mean value was calculated.

Method of determining intestinal tract ischemia: For subjects in whom enterectomy had been performed, ischemia was determined based on the pathological findings. Specifically, necrosis or internal bleeding in the intestinal tract wall was determined as ischemia. For subjects in whom no enterectomy had been performed, the presence of ischemia was determined based on the intestinal tract findings during surgery. Specifically, it was comprehensively determined based on the color of the serosal surface of the bowel or the presence of peristalsis.

A comparative examination was carried out with respect to the CT value of the intestinal tract wall in each scanning phase, the CT value of the solution in the intestinal tract, and the CT value of ascites fluid for a group in whom ischemia was observed (hereafter referred to as Group I) and a group in whom ischemia was not observed (hereafter referred to as Group N) based on the pathological findings or intra-surgical findings.

Moreover, a comparative examination was carried out in Group I subjects for each scanning phase with respect to the average differences in the CT value of the intestinal tract wall where ischemia was suspected and in the intestinal tract wall in non-ischemic areas.

A comparison of the CT value of the intestinal tract wall, the CT value of the solution in the intestine, and the CT value of ascites fluid was analyzed using a Mann-Whitney U test. Differences in the CT value of the intestinal tract wall in each scanning phase in Group I were also compared using a Mann-Whitney U test. When the P value was less than 0.05, it was determined to be statistically significantly different. Analysis was performed using commercially available statistical software (Dr. SPSS II, SPSS for Windows, United States).

There were 15 subjects in Group I and among these, 8 subjects were confirmed based on the pathological findings of an isolated preparation and 7 subjects were determined based on the intra-surgical findings. There were 30 subjects in Group N.

The CT value of the intestinal tract wall was significantly lower in Group I in the arterial phase and portal venous phase. No significant differences were observed in 27 subjects (10 subjects in Group I and 17 subjects in Group N) in whom the equilibrium phase was scanned (Table 1). It was possible to evaluate the CT value of the fluid in the intestinal lumen in 40 subjects (13 subjects in Group I and 27 subjects in Group N), and it was significantly higher in Group I. It was possible to evaluate the CT value of accumulated ascites fluid in 30 subjects (12 subjects in Group I and 18 subjects in Group N) and no significant differences were observed (Table 1).

| Group N (n = 30) | Group I (n = 15) | P value | |

| Arterial phase (n = 45) | 69.6 ± 18.4 | 41.8 ± 11.2 | < 0.001 |

| Portal venous phase (n = 45) | 80.7 ± 17.7 | 60.6 ± 14.6 | 0.001 |

| Late phase (n = 31) | 71.9 ± 10.5 (n = 20) | 64.1 ± 17.5 (n = 11) | 0.113 |

| Ascites (n = 31) | 14.0 ± 4.89 (n = 19) | 17.2 ± 6.48 (n = 12) | 0.287 |

| Fluid in the intestinal lumen (n = 45) | 10.4 ± 5.1 (n = 30) | 18.6 ± 9.5 (n = 15) | 0.003 |

The average differences in the CT values between the ischemic bowel wall and the non-ischemic bowel wall in each subject in Group I were measurable in 14 subjects, excluding one subject in whom ischemia was observed in all intestines in the small intestine axis rotation. Among these, the equilibrium phase was scanned in 10 subjects. The difference in the CT value between the ischemic bowel wall and the non-ischemic bowel wall in the arterial phase, portal venous phase, and equilibrium phase were 33.7 ± 20.1 HU, 12.4 ± 15.0 HU, and 15.0 ± 13.0 HU, respectively. Compared to the other two phases, the difference in the arterial phase was significantly greater.

There are a number of reports claiming that CT tests are useful in the diagnosis of strangulation ileus. Regarding the CT findings of strangulation ileus, poor contrast of the intestinal tract wall[6-10], edema and thickening of the mesentery[6], pneumatosis of the intestinal tract[7], convergence of mesentery or axle-shaped change[9], accumulation of ascites fluids[11], elevation of the CT value of the solution in the intestinal tract [19], etc., have been reported.

Strangulation ileus is associated with ischemia of the intestinal tract and is an emergency surgical indication. It is comparatively easy to diagnose cases clearly having necrosis or cases resulting in necrosis, making it less difficult to determine the surgical indication; however, it may become difficult to determine emergency surgery for cases of non-typical image findings or for cases of poor physical findings. In these cases, enterectomy can be avoided by diagnosing the intestinal tract ischemia at an early stage and performing surgery, making it possible to improve the mortality rate.

In this retrospective study, no significant differences were observed in the CT value in the equilibrium phase for the ischemic bowel wall compared to that of the non-ischemic bowel wall; however, the value was significantly lower in the arterial phase and the portal vein phase. This suggests the possibility that the intestinal tract ischemia at an early stage, which cannot be captured by means of scanning in the equilibrium phase, can be captured by means of scanning in the arterial phase and the portal vein phase. Moreover, when the mean differences in the CT value between the ischemic bowel wall and the non-ischemic bowel wall were compared for cases of ischemia between scanning phases, the difference in the arterial phase was significantly larger than the difference in the portal vein phase and the equilibrium phase. The larger the difference in the CT value, the more contrast is provided on the image, making it possible to visibly capture it; therefore, scanning in the arterial phase was considered most useful in the early diagnosis of the intestinal tract ischemia (Figure 2).

In the study of the CT value for ascites fluid and the solution in the intestinal tract, no significant differences were observed between Group I and Group N for the ascites fluid; however, the value was significantly higher in Group I for the solution in the intestinal tract. This is considered to be indicative of texture change of the liquid contents associated with ischemia and necrosis of the mucous membrane appearing in the initial stage of strangulation ileus. However, the difference in the mean value of the CT value is low, at less than 10 Hounsfield Unit, making it impossible to capture visibly.

The mechanism by which the contrast effect of the arterial phase decreases in the ischemic bowel wall is not clear. Chou et al[20] reported that the hemodynamics of the strangulated and closed-looped intestinal tract wall reach a similar state to venous occlusion of the mesentery. That is, the artery blood flow in the strangulated mesentery is at a higher pressure, causing the venous blood flow to be interrupted first and only the artery blood flow to continuously flow in, thus resulting in an increase in the systematic pressure inside the intestinal tract wall and a decrease in the artery blood flow. According to the scanning of the arterial phase, it is believed to be possible to capture this blood flow change at an early stage, leading to early diagnosis of strangulation.

There are some limitations associated with this study. The scanning timing in the arterial phase is set at 30 s after injection of the contrast agent; however, it has been mentioned that the actual arterial phase varies depending on age and general condition[21-26]. It is believed that it would have been possible to evaluate more accurately the arterial phase scanning if a computer-assisted automatic bolus-tracking technique had been used. Moreover, this is a retrospective study in patients in whom treatment had been completed; therefore, it is necessary to study the diagnosability with respect to strangulation ileus of the arterial phase scanning in prospective clinical studies in the future.

This is a retrospective study using a small number of subjects; however, our findings suggest that CT scanning in the arterial phase may be useful for making an early diagnosis of strangulation ileus.

Strangulation ileus is an intestinal obstruction associated with ischemia of the intestinal tract which, if left untreated, results in intestinal necrosis and could thus become fatal if it leads to perforation followed by peritonitis, and it therefore requires timely treatment.

Computed tomography (CT) is reported to be useful for diagnosing strangulation ileus, but few reports have so far discussed the differences in the diagnostic effectiveness of the scanning phase of CT. In this study, the authors demonstrate the usefulness of the arterial phase of dynamic CT for the early detection of strangulation ileus.

This is the first study to show the usefulness of the arterial phase of dynamic CT by measuring the CT value of the ischemic bowel walls.

By scanning the arterial phase of dynamic CT for ileus patients, it may thus be possible to diagnose strangulation earlier, and thus avoid performing unnecessary bowel resections in some cases.

It is worth publishing except for a few minor corrections

Peer reviewers: Francesco Lassandro, MD, Department of Radiology, Monaldi Hospital, Via Leonardo Bianchi, 80129 Napoli, Italy; Wing P Chan, MD, Chief, Department of Radiology, Taipei Medical University-Wan Fang Hospital, 111 Hsing Long Road, Section 3, Taipei 116, Taiwan, China; Paul V Puthussery, MD, DMRD, DNB, MNAMS, Assistant Professor, Department of Radiodiagnosis, Government Medical College, Thrissur, Kochi 683571, India

S- Editor Cheng JX L- Editor Logan S E- Editor Xiong L

| 1. | Megibow AJ. Bowel obstruction. Evaluation with CT. Radiol Clin North Am. 1994;32:861-870. [PubMed] |

| 2. | Bizer LS, Liebling RW, Delany HM, Gliedman ML. Small bowel obstruction: the role of nonoperative treatment in simple intestinal obstruction and predictive criteria for strangulation obstruction. Surgery. 1981;89:407-413. [PubMed] |

| 3. | Bass KN, Jones B, Bulkley GB. Current management of small-bowel obstruction. Adv Surg. 1997;31:1-34. [PubMed] |

| 4. | Sarr MG, Bulkley GB, Zuidema GD. Preoperative recognition of intestinal strangulation obstruction. Prospective evaluation of diagnostic capability. Am J Surg. 1983;145:176-182. [PubMed] |

| 5. | Silen W, Hein MF, Goldman L. Strangulation obstruction of the small intestine. Arch Surg. 1962;85:121-129. [PubMed] |

| 6. | Macari M, Chandarana H, Balthazar E, Babb J. Intestinal ischemia versus intramural hemorrhage: CT evaluation. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2003;180:177-184. [PubMed] |

| 7. | Wiesner W, Khurana B, Ji H, Ros PR. CT of acute bowel ischemia. Radiology. 2003;226:635-650. [PubMed] |

| 8. | Chou CK, Wu RH, Mak CW, Lin MP. Clinical significance of poor CT enhancement of the thickened small-bowel wall in patients with acute abdominal pain. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2006;186:491-498. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Macari M, Megibow AJ, Balthazar EJ. A pattern approach to the abnormal small bowel: observations at MDCT and CT enterography. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2007;188:1344-1355. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 126] [Cited by in RCA: 109] [Article Influence: 6.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Jancelewicz T, Vu LT, Shawo AE, Yeh B, Gasper WJ, Harris HW. Predicting strangulated small bowel obstruction: an old problem revisited. J Gastrointest Surg. 2009;13:93-99. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 86] [Cited by in RCA: 84] [Article Influence: 5.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Furukawa A, Kanasaki S, Kono N, Wakamiya M, Tanaka T, Takahashi M, Murata K. CT diagnosis of acute mesenteric ischemia from various causes. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2009;192:408-416. [PubMed] |

| 12. | Hayakawa K, Tanikake M, Yoshida S, Yamamoto A, Yamamoto E, Morimoto T. CT findings of small bowel strangulation: the importance of contrast enhancement. Emerg Radiol. 2012;Aug 22 [Epub ahead of print]. [PubMed] |

| 13. | Zielinski MD, Eiken PW, Heller S, Lohse CM, Huebner M, Sarr MG, Bannon MP. Prospective, observational validation of a multivariate small-bowel obstruction model to predict the need for operative intervention. J Am Coll Surg. 2011;212:1068–1076. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 72] [Cited by in RCA: 77] [Article Influence: 5.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Fevang BT, Fevang J, Stangeland L, Soreide O, Svanes K, Viste A. Complications and death after surgical treatment of small bowel obstruction: A 35-year institutional experience. Ann Surg. 2000;231:529-537. [PubMed] |

| 15. | Frager DH, Baer JW. Role of CT in evaluating patients with small-bowel obstruction. Semin Ultrasound CT MR. 1995;16:127-140. [PubMed] |

| 16. | Frager D, Baer JW, Medwid SW, Rothpearl A, Bossart P. Detection of intestinal ischemia in patients with acute small-bowel obstruction due to adhesions or hernia: efficacy of CT. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1996;166:67-71. [PubMed] |

| 17. | Frager D, Medwid SW, Baer JW, Mollinelli B, Friedman M. CT of small-bowel obstruction: value in establishing the diagnosis and determining the degree and cause. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1994;162:37-41. [PubMed] |

| 18. | Zalcman M, Van Gansbeke D, Lalmand B, Braudé P, Closset J, Struyven J. Delayed enhancement of the bowel wall: a new CT sign of small bowel strangulation. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 1996;20:379-381. [PubMed] |

| 19. | Miyaki Y, Yamaguchi A, Isogai M, Harada T, Kaneoka Y, Kamei K, Washizu J, Aikawa K, Kobayashi T. Utility of CT Measurement of Fluid Accumulated in the Expanded Intestinal Lumen in the Diagnosis of Strangulated Small Bowel Obstruction. Jpn J Gastroenterol Surg. 2008;41:464-468. |

| 20. | Chou CK. CT manifestations of bowel ischemia. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2002;178:87-91. [PubMed] |

| 21. | Mehnert F, Pereira PL, Trübenbach J, Kopp AF, Claussen CD. Biphasic spiral CT of the liver: automatic bolus tracking or time delay? Eur Radiol. 2001;11:427-431. [PubMed] |

| 22. | Bae KT. Peak contrast enhancement in CT and MR angiography: when does it occur and why? Pharmacokinetic study in a porcine model. Radiology. 2003;227:809–816. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 177] [Cited by in RCA: 165] [Article Influence: 7.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Silverman PM, Roberts SC, Ducic I, Tefft MC, Olson MC, Cooper C, Zeman RK. Assessment of a technology that permits individualized scan delays on helical hepatic CT: a technique to improve efficiency in use of contrast material. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1996;167:79-84. [PubMed] |

| 24. | Sandstede J, Tschammler A, Beer M, Vogelsang C, Wittenberg G, Hahn D. Optimization of automatic bolus tracking for timing of the arterial phase of helical liver CT. Eur Radiol. 2001;11:1396–1400. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 51] [Cited by in RCA: 53] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Kim T, Murakami T, Hori M, Takamura M, Takahashi S, Okada A, Kawata S, Cruz M, Federle MP, Nakamura H. Small hypervascular hepatocellular carcinoma revealed by double arterial phase CT performed with single breath-hold scanning and automatic bolus tracking. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2002;178:899-904. [PubMed] |

| 26. | Itoh S, Ikeda M, Achiwa M, Satake H, Iwano S, Ishigaki T. Late-arterial and portal-venous phase imaging of the liver with a multislice CT scanner in patients without circulatory disturbances: automatic bolus tracking or empirical scan delay? Eur Radiol. 2004;14:1665–1673. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 39] [Cited by in RCA: 43] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |