Published online Jul 28, 2011. doi: 10.4329/wjr.v3.i7.182

Revised: July 8, 2011

Accepted: July 15, 2011

Published online: July 28, 2011

Visceral artery aneurysms (VAAs) include aneurysms of the splanchnic circulation and those of the renal artery. Their diagnosis is clinically important because of the associated high mortality and potential complications. Splenic, superior mesenteric, gastroduodenal, hepatic and renal arteries are some of the common arteries affected by VAAs. Though surgical resection and anastomosis still remains the treatment of choice in some of the cases, especially cases involving the proximal arteries, increasingly endovascular treatment is being used for more distal vessels. We present a pictorial review of various intra-abdominal VAAs and their endovascular management.

- Citation: Jana M, Gamanagatti S, Mukund A, Paul S, Gupta P, Garg P, Chattopadhyay TK, Sahni P. Endovascular management in abdominal visceral arterial aneurysms: A pictorial essay. World J Radiol 2011; 3(7): 182-187

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1949-8470/full/v3/i7/182.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4329/wjr.v3.i7.182

The entity of visceral artery aneurysms (VAAs) includes aneurysms of the splanchnic circulation and those of the renal artery. Aneurysms of the splanchnic circulation include aneurysms of the celiac trunk, superior mesenteric artery (SMA), inferior mesenteric artery or their branches. Though rare, their diagnosis remains clinically important because of the high mortality and potential complications associated with them[1,2].

Splenic artery aneurysms (SAAs) are the most common, comprising more than half the VAAs, followed in frequency by aneurysms of the hepatic artery (20%), SMA (5%), celiac trunk (4%) and other branches of the celiac and SMA[2]. The inferior mesenteric artery is a rare site for VAAs. Renal artery aneurysms are relatively common but have a natural history which is distinct from that of splanchnic artery aneurysms.

True aneurysms have all the layers of the arterial wall intact, whereas a pseudoaneurysm is defined as a pulsating, encapsulated hematoma communicating with the lumen of the ruptured vessel. Most true VAAs are degenerative. Atherosclerosis, vasculitis, and fibromuscular dysplasia are other causes of true VAAs. Pseudoaneurysms may occur secondary to iatrogenic or non-iatrogenic trauma, tumors, infection (mycotic) and rarely in the setting of atherosclerotic ulcer or primary or secondary vasculitis.

Management can be surgical or endovascular. In general, endovascular repair is preferred for most VAAs. General indications for treatment of VAAs include: a size greater than twice the caliber of the artery; rapidly increasing size; symptomatic aneuryms; aneurysms in women of child-bearing age group due to a high risk of rupture; and mycotic aneurysms.

Metallic coils can be used alone or along with Gelfoam. Gelfoam (pledget or slurry form) can be used as a temporary embolizing agent, whereas coils act as permanent agents. Coils should be used in the appropriate size because use of small size of coil may lead to distal embolization and inadequate occlusion, whereas larger size of coil prevents the coil from achieving its shape.

Cyanoacrylate glue is another, less commonly, used embolizing material in VAAs. Use of glue needs special precautions, which take the form of using non-ionic solutions such as lipiodol for mixing and dextrose for catheter flushing.

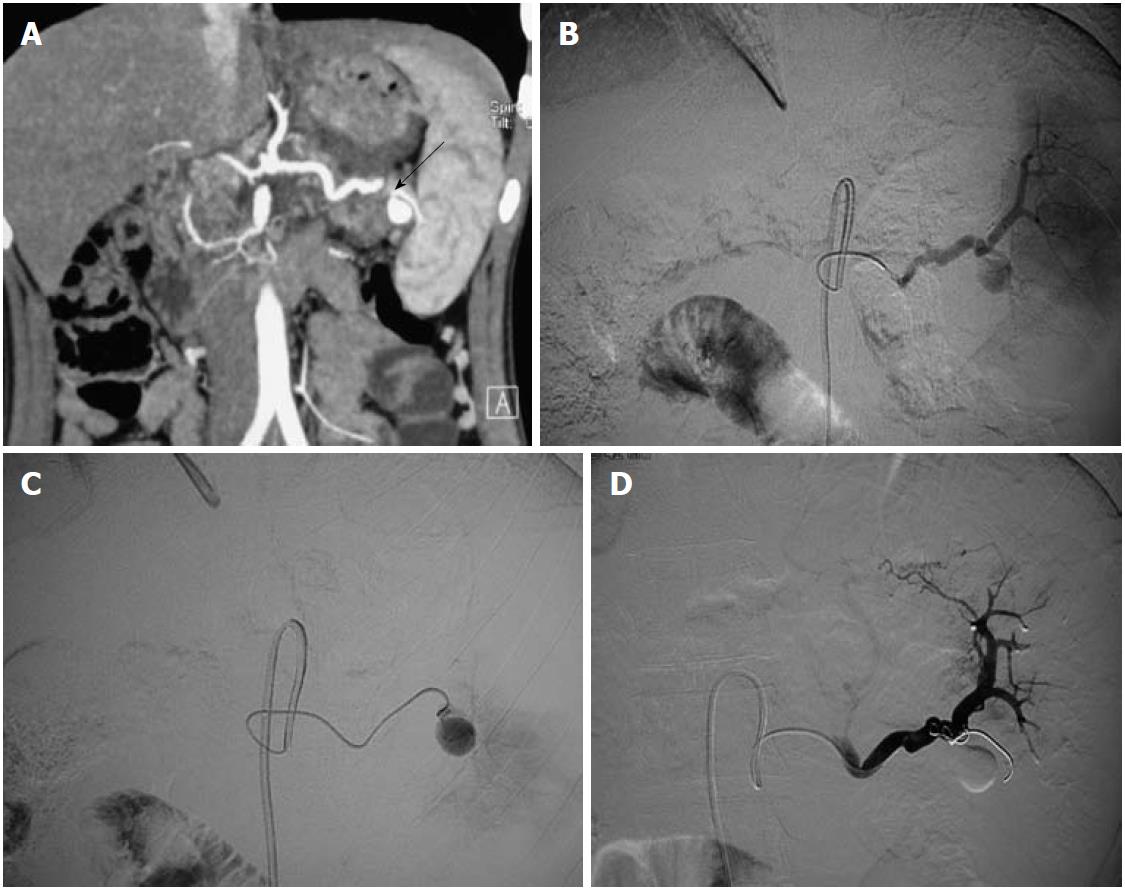

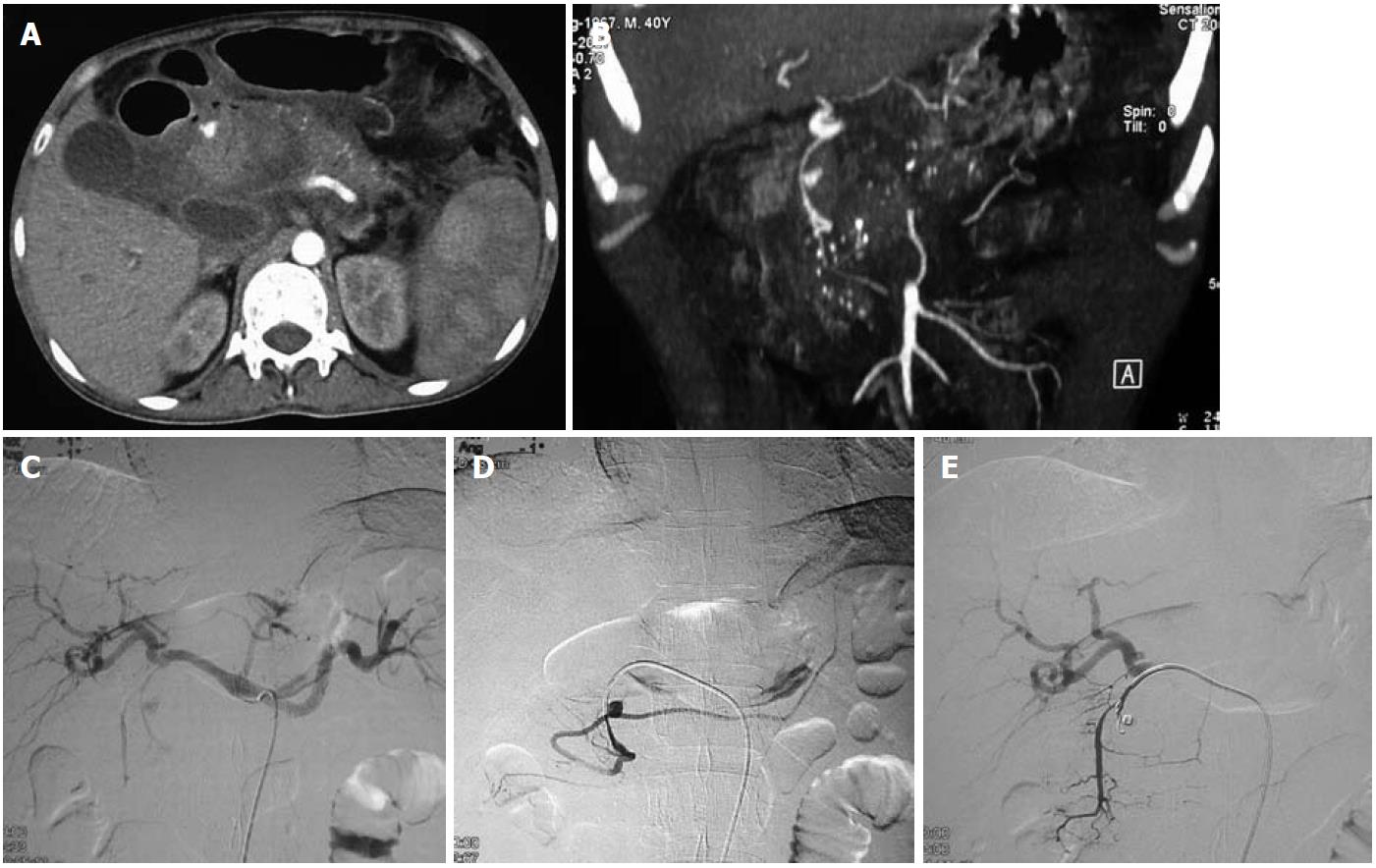

SAAs (Figure 1) account for 60% of all VAAs. Multiparous females are most commonly affected. Etiology is multifactorial but the most common underlying pathogenetic mechanism is the degeneration of the elastic fibres of the media as a result of exposure to estrogen[3]. The most common site is the middle or distal segment of the splenic artery at the point of branching. SAAs are usually small (< 2 cm), and saccular. They are incidentally diagnosed on imaging, carry up to 10% risk of rupture, and should be considered in the differential diagnosis of acute abdominal pain with shock. Multiple aneurysms and aneurysms from the anomalous origin of the splenic artery from the SMA have been reported.

Endovascular treatment using coil embolization is preferred for distal aneurysms, whereas stent grafts are suitable for the proximal location[4].

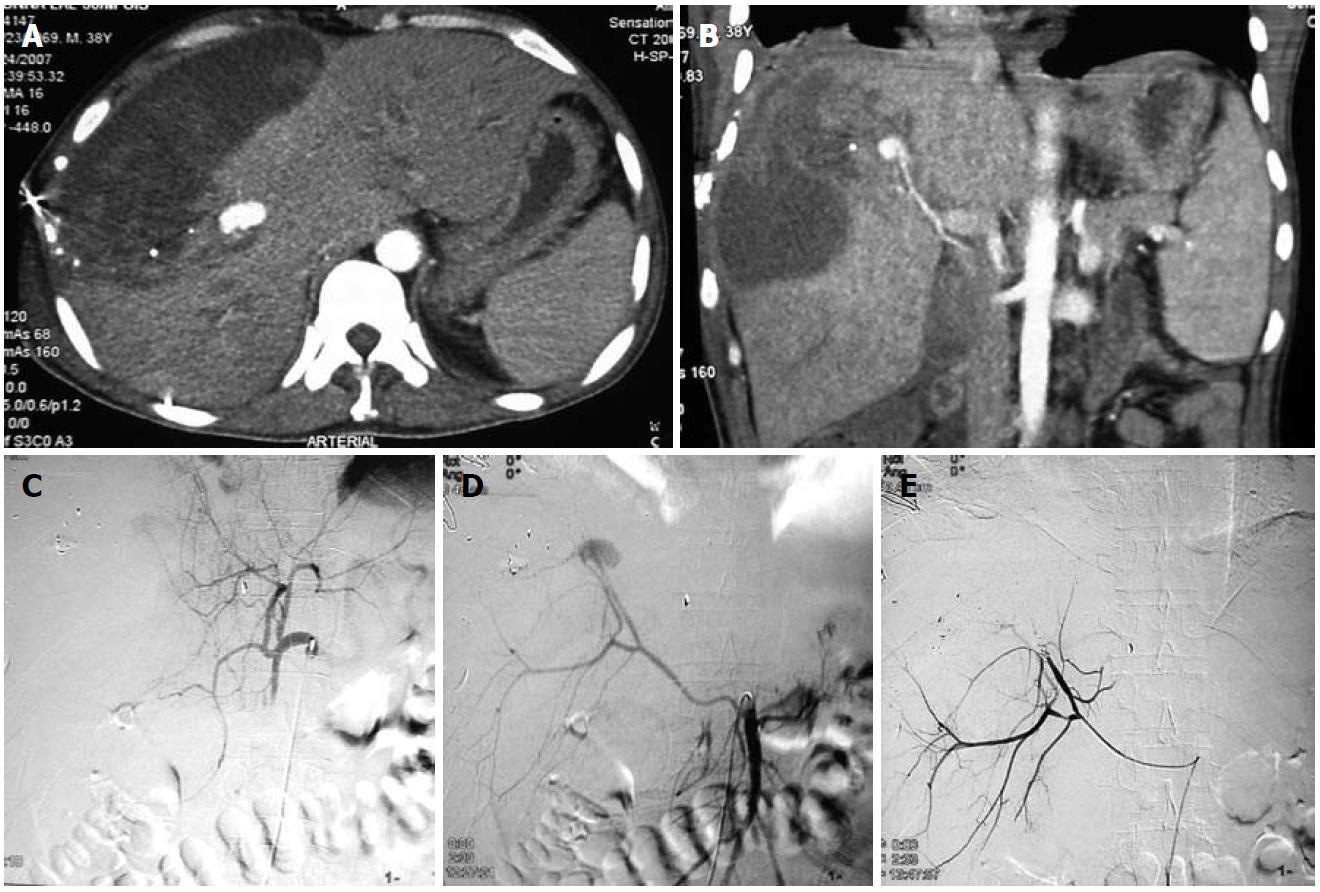

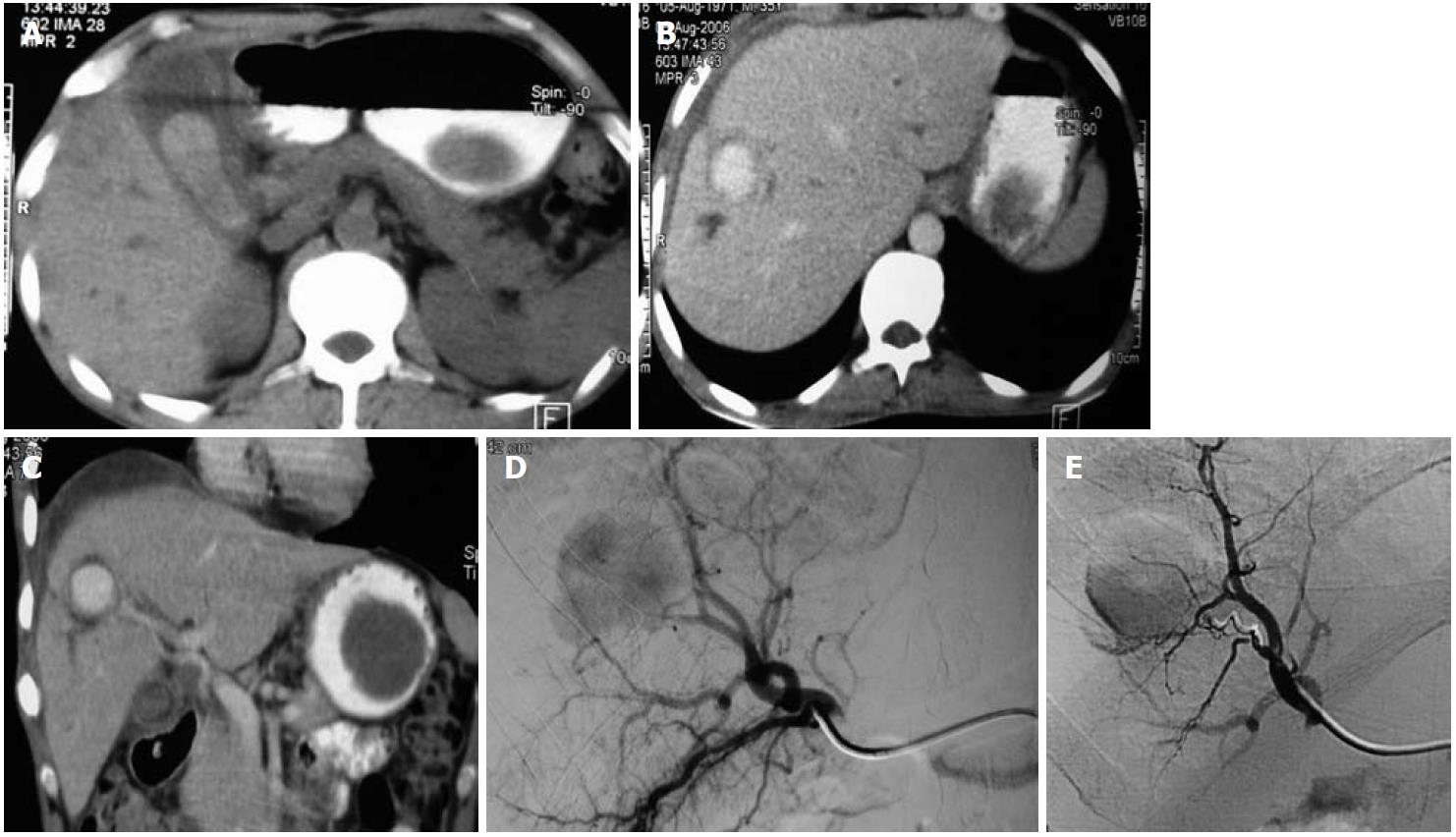

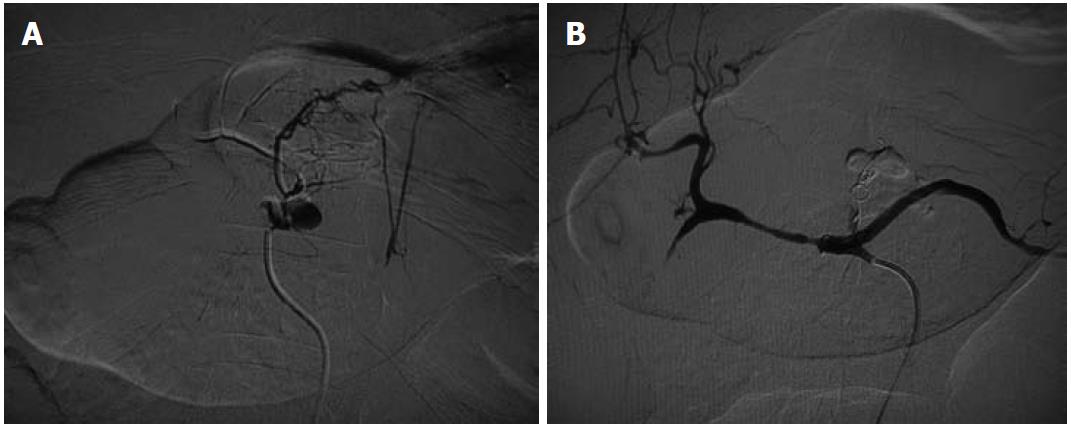

Hepatic artery aneurysms (HAAs) are more common in men. Around half of the HAAs are iatrogenic, associated with interventional biliary procedures, with the rest being related to trauma (Figures 2 and 3), infection, vasculitis and atherosclerosis[3]. Most are asymptomatic, with symptomatic HAAs causing acute epigastric pain, jaundice and hemobilia. The risk of rupture is 20%-40%. The majority of HAAs are solitary, saccular and extrahepatic.

An aneurysm distal to the origin of the gastroduodenal artery (GDAs) should be treated with excision and reconstruction; whereas a lesion proximal to this point can be treated by embolization, because the hepatic perfusion is made up by the gastroduodenal and right gastric arteries. Intrahepatic aneurysms can be treated by embolization[5].

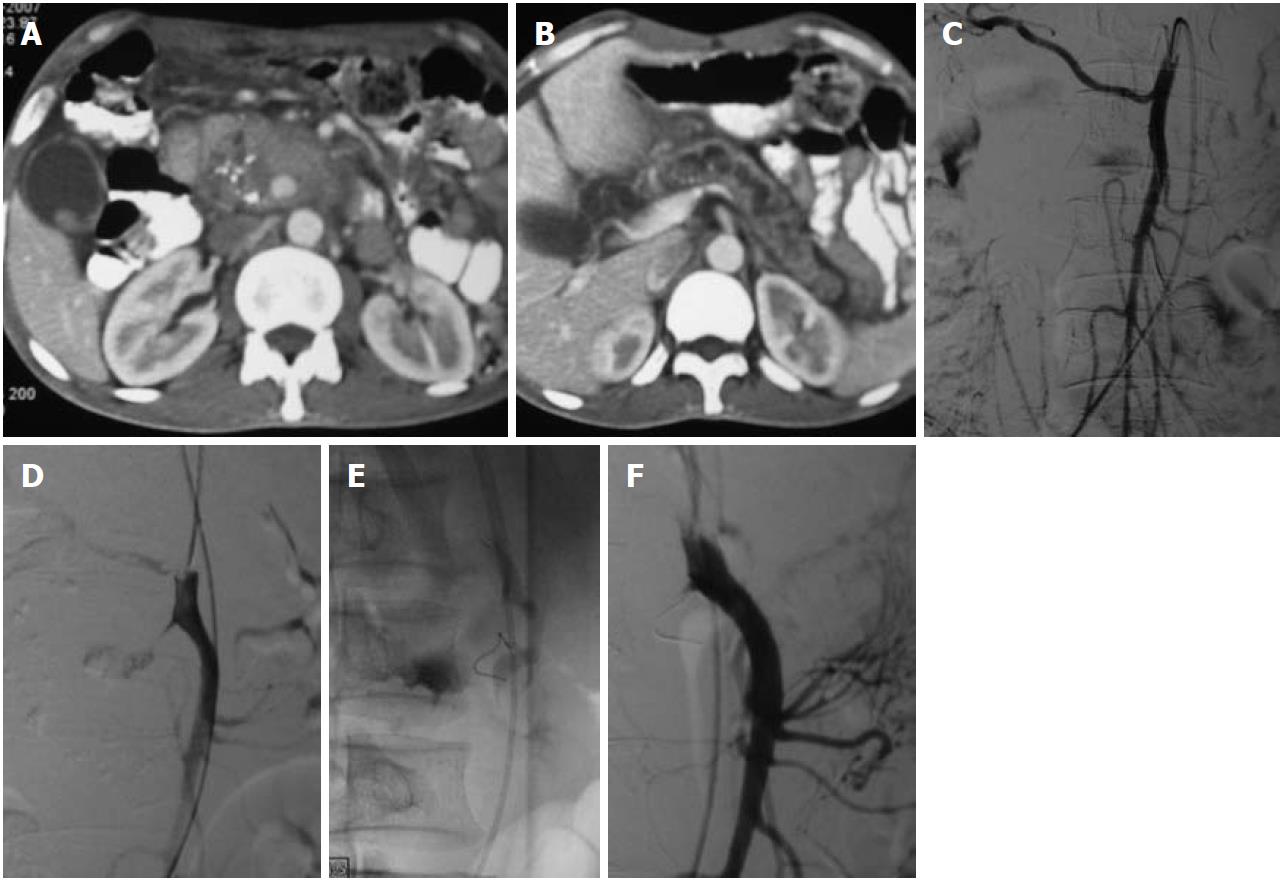

The most common cause of SMA aneurysms is infection secondary to infective endocarditis or in the setting of drug abuse. Unlike other VAAs, SMA aneurysms are symptomatic and are more likely to become thrombosed than to rupture. Usually located in the proximal SMA, they present with mesenteric ischemia[2]. The conventional treatment is surgical, but endovascular treatment (stent, coil) has also been successful[2] (Figure 4).

Celiac artery aneurysms (CAAs) are frequently symptomatic, and have high complication and mortality rates. They are usually fusiform and arise from the distal third of the trunk. A few cases of CAAs arising from anomalous common celiomesenteric trunk have been reported[6]. Association of CAAs with other splanchnic and abdominal aortic aneurysms is relatively common.

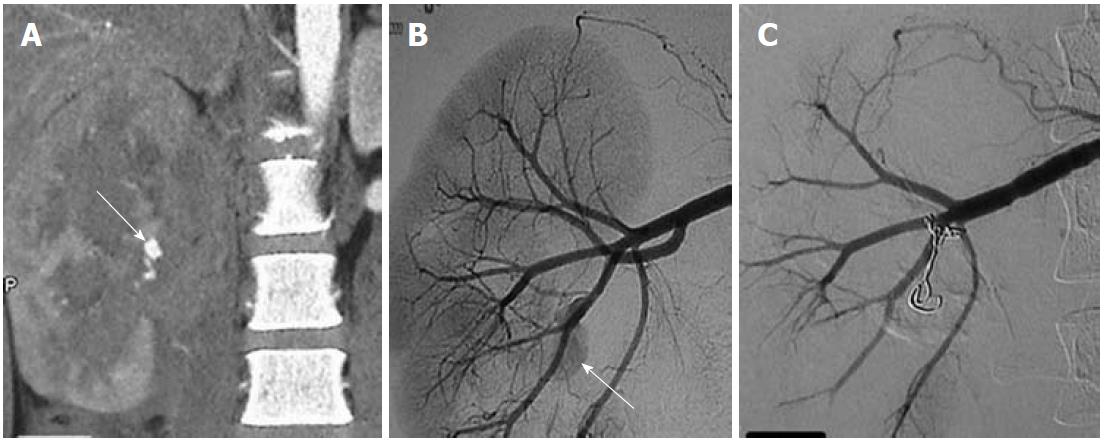

These are frequently related to inflammation in and around the pancreas related to acute or chronic pancreatitis (Figure 5) with erosion of the pseudocysts into the vessels. Unlike other VAAs, most are symptomatic and present as intraperitoneal, retroperitoneal or gastrointestinal hemorrhage. Coil embolization is an accepted form of treatment. When performing embolization in saccular aneurysms of the GDAs, either isolation of the aneurysm neck or both proximal and distal embolization should be performed rather than proximal embolization alone, as the aneurysm may recruit a new vascular supply in a retrograde manner.

Most of these are degenerative in origin and encountered in elderly men (Figure 6). They carry a very high (90%) risk of rupture into the stomach or the peritoneum and relatively high mortality rates.

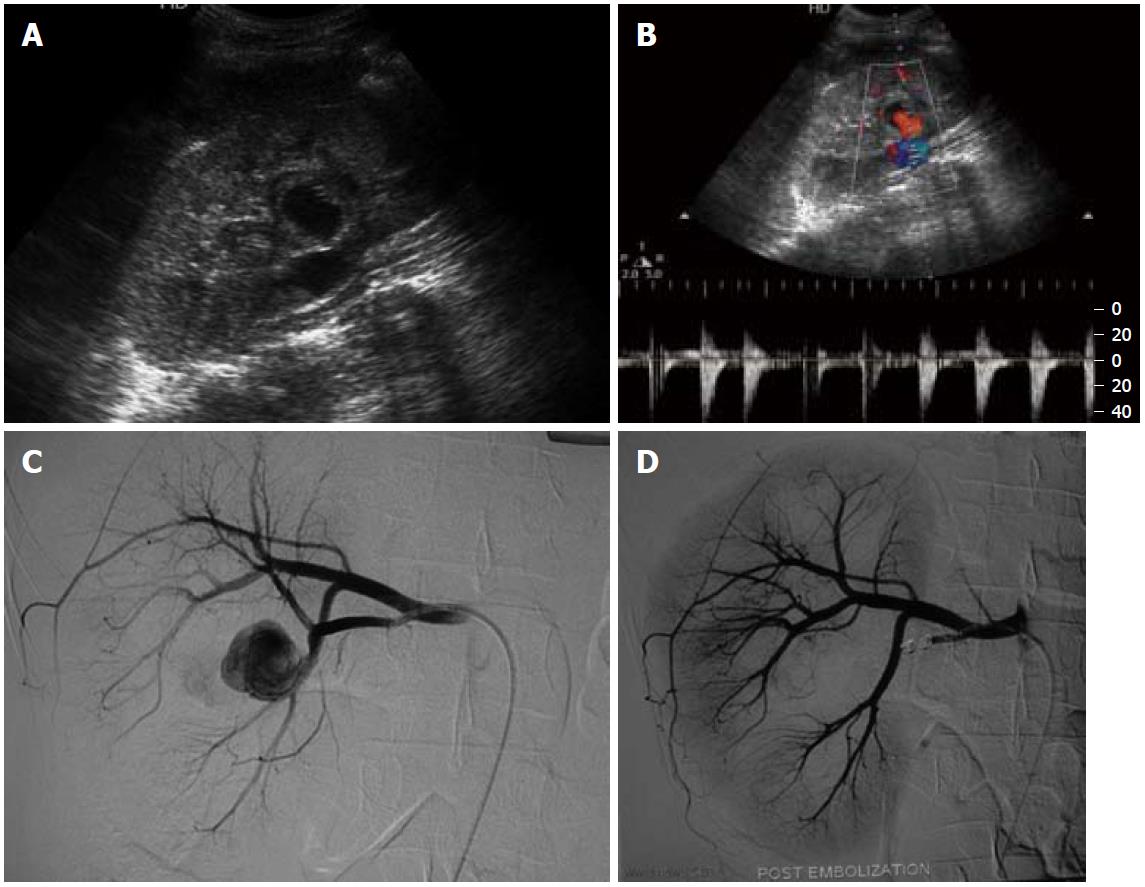

Renal artery aneurysms (RAAs) are distinct from other VAAs, in that they have a low risk of rupture with resultant low mortality rates and frequent association with hypertension, though the cause and effect relationship with hypertension is unclear[7]. RAAs are among the most common VAAs (Figures 7 and 8). They are more common in females, with fibromuscular dysplasia being the most common etiology, and atherosclerosis, vasculitis and trauma being the other common causes. The most common location is outside the renal parenchyma at the primary or secondary bifurcation. They are frequently saccular and calcification is rare.

Peer reviewer: Barbaros E Çil, MD, Associated Professor of Radiology, Department of Radiology,Hacettepe University School of Medicine, S?hhiye 06100, Ankara, Turkey

S- Editor Cheng JX L- Editor Logan S E- Editor Zheng XM

| 1. | Shanley CJ, Shah NL, Messina LM. Common splanchnic artery aneurysms: splenic, hepatic, and celiac. Ann Vasc Surg. 1996;10:315-322. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 208] [Cited by in RCA: 181] [Article Influence: 6.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Liu Q, Lu JP, Wang F, Wang L, Jin AG, Wang J, Tian JM. Visceral artery aneurysms: evaluation using 3D contrast-enhanced MR angiography. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2008;191:826-833. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Hallett JW. Splenic artery aneurysms. Semin Vasc Surg. 1995;8:321-326. [PubMed] |

| 4. | Gabelmann A, Görich J, Merkle EM. Endovascular treatment of visceral artery aneurysms. J Endovasc Ther. 2002;9:38-47. [PubMed] |

| 5. | O'Driscoll D, Olliff SP, Olliff JF. Hepatic artery aneurysm. Br J Radiol. 1999;72:1018-1025. [PubMed] |

| 6. | Detroux M, Anidjar S, Nottin R. Aneurysm of a common celiomesenteric trunk. Ann Vasc Surg. 1998;12:78-82. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Nosher JL, Chung J, Brevetti LS, Graham AM, Siegel RL. Visceral and renal artery aneurysms: a pictorial essay on endovascular therapy. Radiographics. 2006;26:1687-704; quiz 1687. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 124] [Cited by in RCA: 118] [Article Influence: 6.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |