Published online Aug 28, 2010. doi: 10.4329/wjr.v2.i8.334

Revised: May 27, 2010

Accepted: June 4, 2010

Published online: August 28, 2010

Primary lymphoma that involves the esophagus is very rare, with fewer than 30 cases reported in the English-language literature. Non-Hodgkin lymphoma accounts for most of the cases. Esophageal lymphomas have varied radiological appearances, which poses diagnostic difficulty. We report two cases of histopathologically confirmed primary diffuse large B-cell esophageal lymphoma and describe their radiological features, and briefly review the literature.

- Citation: Ghimire P, Wu GY, Zhu L. Primary esophageal lymphoma in immunocompetent patients: Two case reports and literature review. World J Radiol 2010; 2(8): 334-338

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1949-8470/full/v2/i8/334.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4329/wjr.v2.i8.334

The gastrointestinal (GI) tract is the most common extranodal site for involvement by non-Hodgkin lymphoma[1]. Esophageal lymphoma accounts for < 1% of all GI lymphomas, and usually results from metastasis from the cervical or mediastinal lymph nodes or extension of a gastric lymphoma[2]. Primary esophageal lymphoma in immunocompetent patient is very rare[3-5]. Furthermore, imaging findings of esophageal lymphoma are nonspecific, thus posing a diagnostic dilemma[6,7]. We report two histopathologically confirmed cases of diffuse large B-cell non-Hodgkin lymphomas, describe their radiological and endoscopic features, and briefly review the literature.

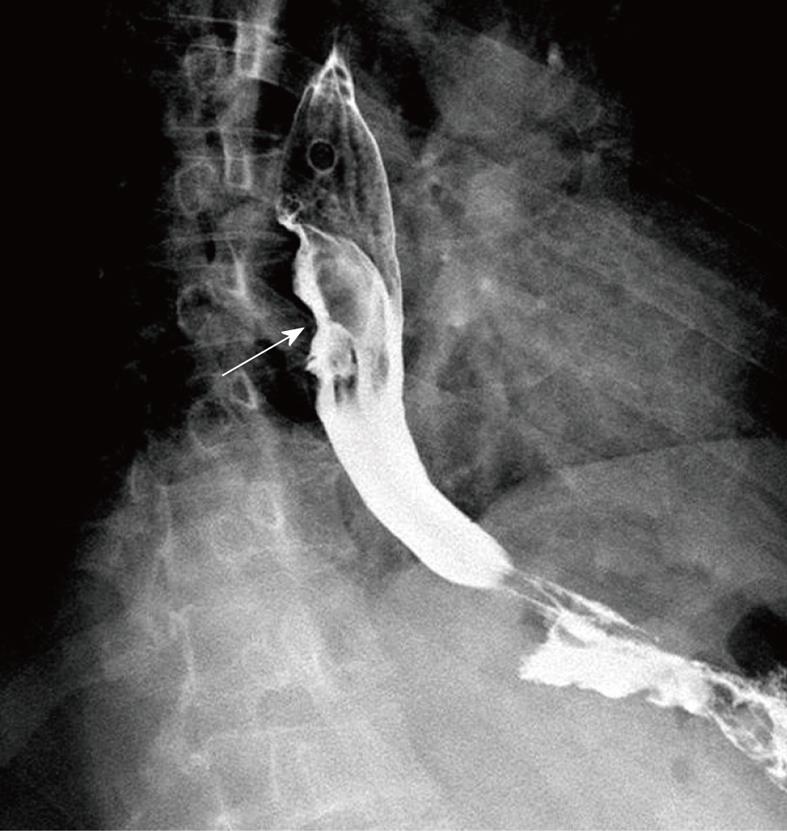

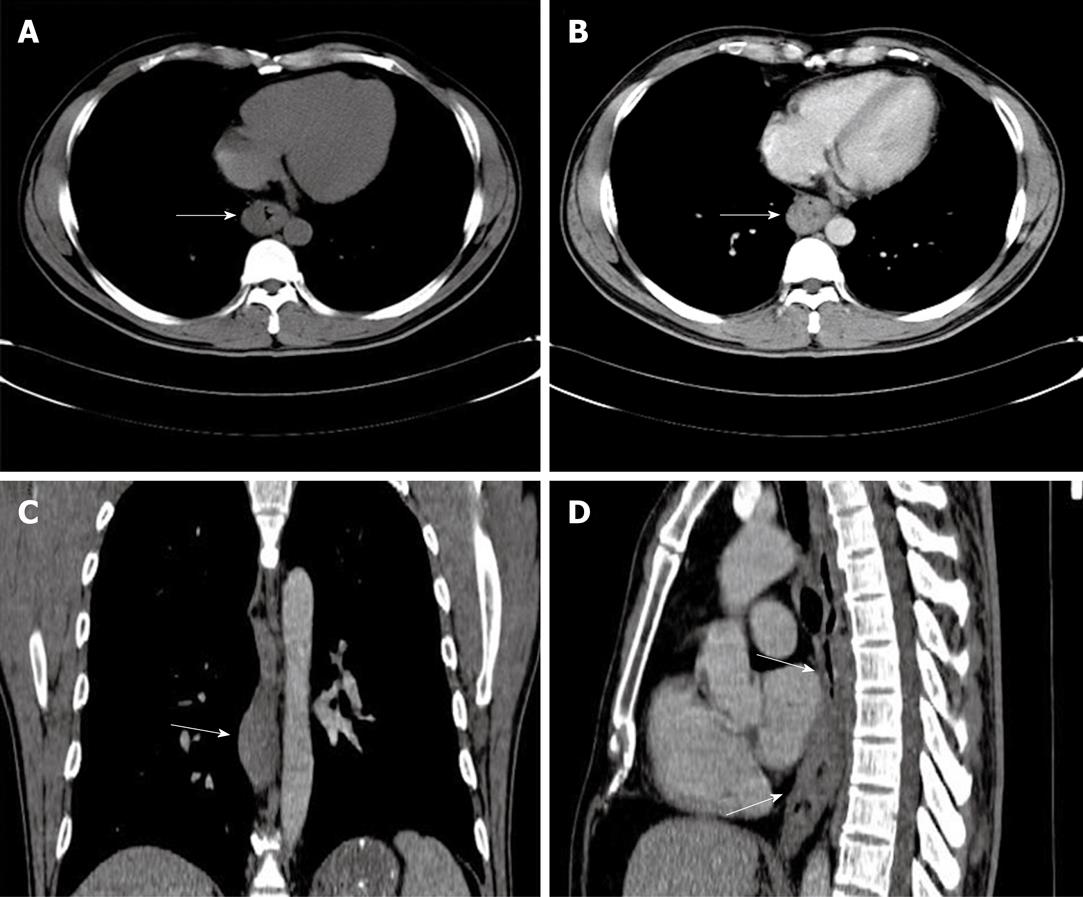

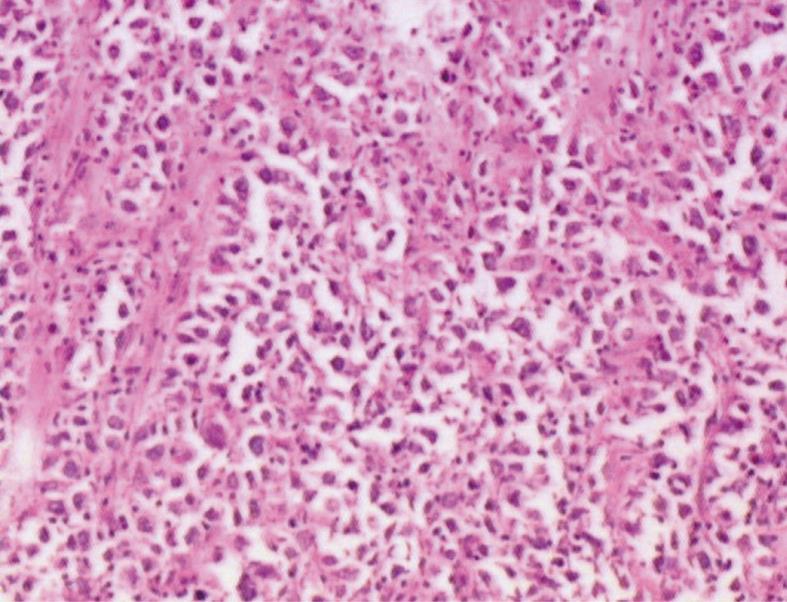

A 41-year-old man came to our hospital in April 2009 for evaluation of progressive dysphagia that was present only with solid food ingestion over the previous 1 mo. He had no other complaint and no evidence of any immunosuppressive disease, and physical examination, laboratory findings, chest radiography, and abdominal ultrasonography were unremarkable. Barium esophagography revealed an irregular wavy outline as a filling defect, with evidence of significant short segment narrowing of the distal esophagus that involved mainly the right side posterolaterally (Figure 1). Esophagogastroduodenoscopy revealed an esophageal ulcer starting at 32 cm of incisor teeth which measured approximately 1.8 cm × 1.4 cm. The remaining esophagus was irregular and erythematous. The stomach and duodenum were normal in appearance. Biopsy specimens were taken from multiple sites of the esophagus, and revealed fibrin necrotic exudates with no evidence of dysplasia or neoplastic cells. Computed tomography (CT) of the thorax demonstrated asymmetric circumferential thickening of the esophageal wall that extended from the level of the carina to the diaphragm, which resulted in narrowing of the esophageal lumen. The gastroesophageal junction appeared normal. The fat plane between the thickened esophageal wall and surrounding structures was well maintained (Figure 2). There was no cervical or mediastinal lymphadenopathy. CT of the abdomen and pelvis was normal. The patient underwent subtotal esophagectomy with gastric pull-up reconstruction, along with radical thoracic and abdominal lymphadenectomy. Histological examination of the biopsy specimen from the mass was suggestive of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (Figure 3). An immunohistochemical study confirmed an LCA-positive B-cell phenotype that stained positively for B-cell markers CD20 and CD79, and negatively for T-cell markers CD3 and CD5. Bone marrow biopsy specimens from the iliac crest were negative for lymphoma cells. In accordance with the Ann Arbor classification system, this was a stage IEA lymphoma of the esophagus. The patient recovered well from surgery. Postoperatively, he was treated with six cycles of immunochemotherapy in the form of R-CHOP (anti-CD20 monoclonal antibody rituximab, with cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine sulfate and prednisolone) followed by irradiation. The patient achieved complete remission. Follow-up investigations ruled out any relapse and he was disease free until this article was written.

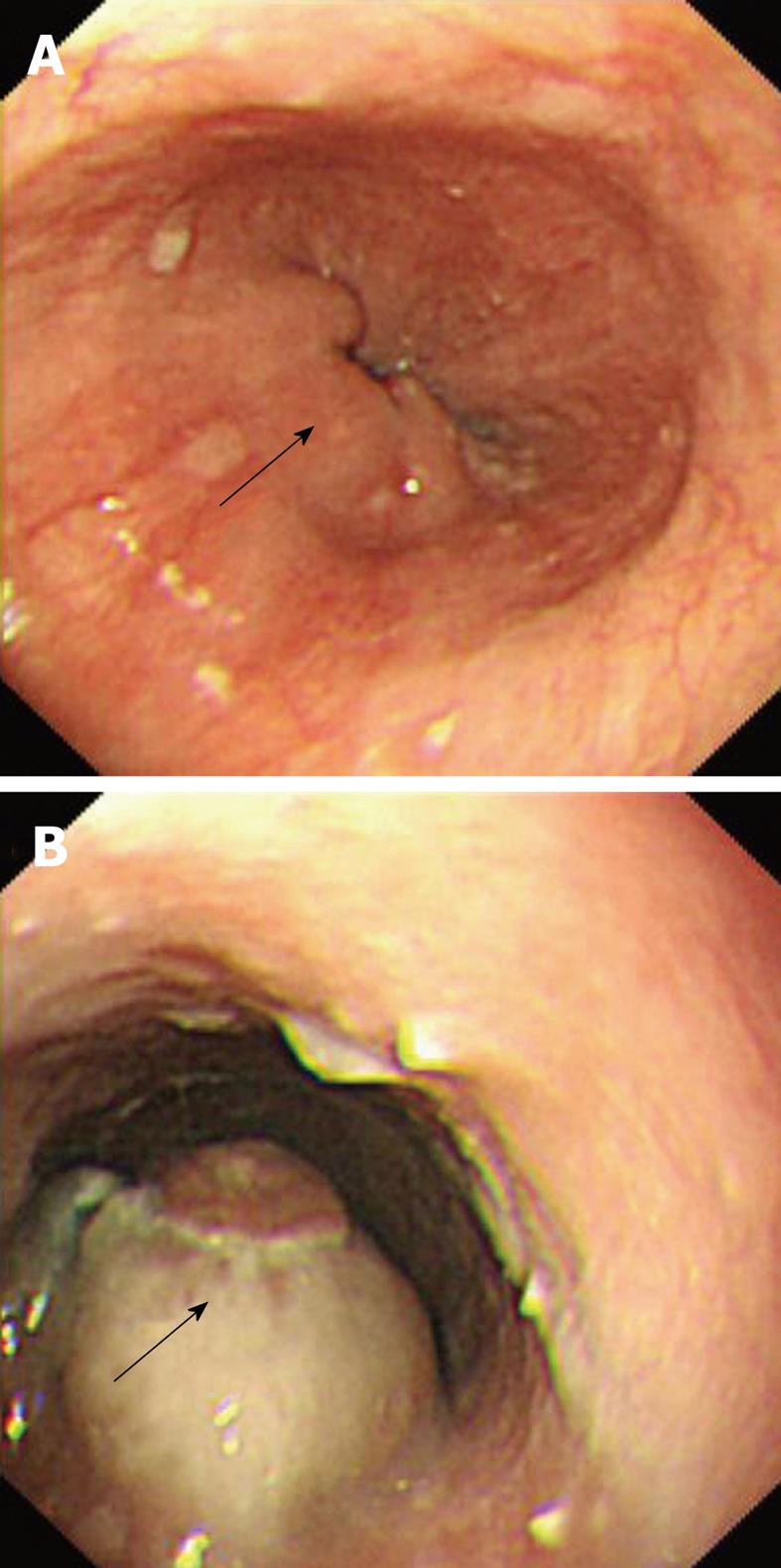

A 77-year-old man was referred from another hospital for further workup and management of his illness. He had complained of dysphagia for solid food with loss of appetite for the past 2 mo. His past medical history was unremarkable except for hypertension, for which he had been taking antihypertensive drugs. His physical examination was not significant and did not reveal any signs that were suggestive of immune suppression. Blood parameters and serum chemistry were all within normal limits. The investigations performed in the other hospital included barium esophagography that showed multiple filling defects in the distal segment of the esophagus. Esophagogastroduodenoscopy showed multiple solid, irregular and firm nodular lesions starting at 27-31 cm from the incisor teeth, and the rest of the esophagus, stomach and duodenum was normal. Endoscopic biopsy specimens from the lesion were inconclusive for a diagnosis. Chest CT demonstrated concentric thickening of the esophageal wall, with slight enlargement of the subcarinal lymph nodes. The remaining thoracic CT and abdominal and pelvic CT were normal. Repeat esophagogastroduodenoscopy performed in our institution also demonstrated similar endoscopic findings (Figure 4). Multiple endoscopic biopsies were required from the lesion before pathological evaluation revealed the diagnosis of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, which was confirmed by immunohistochemistry. A bone marrow biopsy was done from the iliac crest, which did not show any evidence of malignancy. After disclosure of the diagnosis, the patient refused further investigation and declined treatment, and was discharged on request.

The GI tract is the most common extranodal site for non-Hodgkin lymphoma, and accounts for 5%-20% of all cases, whereas some autopsy studies have revealed almost 50% involvement[1]. The stomach is the most common of the GI sites to be involved (48%-50%), followed by small intestine (30%-37%), and ileocecal region (12%-13%). The esophagus is a distinctly rare site to be involved and accounts for < 1% of all GI lymphomas[2]. Esophageal involvement usually results from metastasis from cervical or mediastinal lymph nodes or extension from gastric lymphoma. Primary esophageal lymphoma is an extremely rare occurrence, with fewer than 30 cases reported in the literature, with the majority being diffuse large B-cell type non-Hodgkin lymphomas. The age of presentation of the disease is highly variable. The etiology of the disease is unknown, with the role of Epstein-Barr virus being controversial. It has been noticed that it is most common in immunocompromised patients, with HIV infection as a probable risk factor[3-5]. Radiological and endoscopic findings of esophageal lymphoma are very varied and are nonspecific, which poses diagnostic challenges when differentiating it from other benign and malignant lesions[6,7].

Ann Arbor (AA) staging with Cotswold modification is now universally adopted for Hodgkin’s as well as non-Hodgkin lymphoma. However, this staging has a number of shortcomings that are related to the different pattern of disease presentation in non-Hodgkin lymphoma, its inability to incorporate the grade of the tumor, as well as disease prognosis. Many types of lymphoma, particularly the indolent B-cell non-Hodgkin’ lymphoma have bone marrow involvement in most cases, thus characterizing them as stage IV by AA staging. As bone marrow involvement does not independently confer a worse prognosis, this staging has a limited predictive value, thus warranting further workup[8].

The various radiographic patterns that have been described in the literature for esophageal lymphoma include stricture, ulcerated mass, multiple submucosal nodules, varicoid pattern, achalasia-like pattern, progressive aneurysmal dilatation, and tracheoesophageal fistula formation, with none being diagnostic[9-11]. Endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) has gained clinical acceptance for assessment of lymphoma and preoperative staging, because it can accurately depict the structural abnormalities and depth of invasion of the lesions. EUS appearance however is not pathognomonic, with presentation varying as anechoic, hypoechoic or even as hyperechoic masses[12,13]. CT findings of esophageal lymphoma are nonspecific and not diagnostic, with features such as thickening of the wall mimicking other common tumors, such as esophageal carcinoma. CT, however, is valuable for the evaluation of the extraluminal component of an esophageal mass, its mediastinal extension, any fistula formation, and status of lymph nodes, therefore, it has a role in disease staging, assisting in stratification of various available treatments, evaluating treatment responses, monitoring patient progress, as well as detection of any relapses. Recently, incorporation of positron emission tomography with CT (PET/CT) has emerged as an indispensable tool in the staging and follow-up of patients with extranodal involvement in Hodgkin’s and non-Hodgkin lymphoma, with increased sensitivity and specificity. Diffuse large B-cell non-Hodgkin lymphoma of the esophagus has been shown to manifest as circumferential thickening of the wall, with diffuse increased fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG) uptake. However, intensity of FDG uptake in lymphoma is influenced by various intrinsic tumor factors such as histological features and grade, as well as various extrinsic factors. With proper correlation, FDG PET/CT has also significantly increased the detection of indolent lesions that were undetected by conventional cross-sectional imaging[14].

In our first patient, the radiological findings were nonspecific to lymphoma. The presence of asymmetric circumferential thickening of esophageal wall is also evident in other malignant lesions such as carcinoma or metastases, or even in some benign lesions[6,7]. Preservation of the fat plane despite the size of the lesion and extent of infiltration was supportive of the diagnosis of lymphoma. Endoscopic features of the lesion preferentially suggested a diagnosis of carcinoma rather than lymphoma. Besides, repeated endoscopic biopsies of the lesion also did not yield a definite diagnosis. This posed a diagnostic difficulty that required further investigation. As management of the case depended on accurate diagnosis, further workup was mandatory to rule out the various possibilities. The definite diagnosis of lymphoma was made by histopathology and immunohistochemistry of the surgically removed specimen. Our patient fulfilled all of Dawson’s criteria for making a retrospective clinical diagnosis of primary lymphoma, which include lesions that are localized to the GI tract with or without regional lymphadenopathy, and the absence of: (1) peripheral lymphadenopathy; (2) mediastinal adenopathy; (3) liver or spleen involvement; and (4) normal peripheral blood counts[15].

In the second patient, radiological findings were too inconclusive for the diagnosis of esophageal lymphoma. The finding of a non-ulcerative submucosal mass by esophagogastroduodenoscopy prompted suspicion of lymphoma, although this feature is also nonspecific and can even be seen in carcinoma as well as other benign submucosal lesions such as leiomyoma. Repeated endoscopic biopsies were required for the final pathological diagnosis, thus emphasizing the difficulty in diagnosis of primary esophageal lymphoma. It has been questioned whether the application of Dawson’s criteria for the diagnosis of primary GI lymphoma holds true for the esophagus. Modifications as exclusion of mediastinal lymphadenopathy in the criteria for primary esophageal lymphoma have been suggested[16]. Of particular interest in our second patient was the finding of a mildly enlarged subcarinal lymph node. We believe that Dawson’s criteria is not appropriate for diagnosis of esophageal lymphoma, because the esophagus is mostly a mediastinal structure that has an extensive lymphatic network with rich mucosal and submucosal lymphatics in the wall, which results in wide lymph node basins. Therefore, based on the predominant lesion in the esophagus of the patient with no involvement of liver, spleen, peripheral lymph nodes and with normal blood parameters we did not consider absence of mediastinal lymphadenopathy as a strict criterion of primary esophageal lymphoma.

To conclude, we have presented two cases of primary esophageal lymphoma in immunocompetent patients highlighting the difficulty in the accurate diagnosis radiologically requiring a tissue diagnosis. Even in immunocompetent patients with dysphagia, in whom radiological findings are equivocal, a high index of suspicion for lymphoma should also be borne in mind, because accurate diagnosis is pivotal to prognosis and deciding on treatment. We also briefly reviewed the literature, with an emphasis on the radiological spectrum of disease presentation.

Peer reviewer: Yasunori Minami, MD, PhD, Division of Gastroenterology and Hepatology, Department of Internal Medicine, 377-2, Ohno-higashi, Osaka-sayama 589-8511, Japan

S- Editor Cheng JX L- Editor Kerr C E- Editor Zheng XM

| 1. | Freeman C, Berg JW, Cutler SJ. Occurrence and prognosis of extranodal lymphomas. Cancer. 1972;29:252-260. |

| 2. | Herrmann R, Panahon AM, Barcos MP, Walsh D, Stutzman L. Gastrointestinal involvement in non-Hodgkin's lymphoma. Cancer. 1980;46:215-222. |

| 3. | Weeratunge CN, Bolivar HH, Anstead GM, Lu DH. Primary esophageal lymphoma: a diagnostic challenge in acquired immunodeficiency syndrome--two case reports and review. South Med J. 2004;97:383-387. |

| 4. | Taal BG, Van Heerde P, Somers R. Isolated primary oesophageal involvement by lymphoma: a rare cause of dysphagia: two case histories and a review of other published data. Gut. 1993;34:994-998. |

| 5. | Radin DR. Primary esophageal lymphoma in AIDS. Abdom Imaging. 1993;18:223-224. |

| 6. | Wagner PL, Tam W, Lau PY, Port JL, Paul S, Altorki NK, Lee PC. Primary esophageal large T-cell lymphoma mimicking esophageal carcinoma: a case report and literature review. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2008;135:957-958, 958.e1. |

| 7. | Kaplan KJ. Primary esophageal lymphoma: a diagnostic challenge. South Med J. 2004;97:331-332. |

| 8. | Armitage JO. Staging non-Hodgkin lymphoma. CA Cancer J Clin. 2005;55:368-376. |

| 9. | Carnovale RL, Goldstein HM, Zornoza J, Dodd GD. Radiologic manifestations of esophageal lymphoma. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1977;128:751-754. |

| 10. | Levine MS, Sunshine AG, Reynolds JC, Saul SH. Diffuse nodularity in esophageal lymphoma. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1985;145:1218-1220. |

| 11. | Coppens E, El Nakadi I, Nagy N, Zalcman M. Primary Hodgkin's lymphoma of the esophagus. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2003;180:1335-1337. |

| 12. | Kalogeropoulos IV, Chalazonitis AN, Tsolaki S, Laspas F, Ptohis N, Neofytou I, Rontogianni D. A case of primary isolated non-Hodgkin's lymphoma of the esophagus in an immunocompetent patient. World J Gastroenterol. 2009;15:1901-1903. |

| 13. | Bolondi L, De Giorgio R, Santi V, Paparo GF, Pileri S, Di Febo G, Caletti GC, Poggi S, Corinaldesi R, Barbara L. Primary non-Hodgkin's T-cell lymphoma of the esophagus. A case with peculiar endoscopic ultrasonographic pattern. Dig Dis Sci. 1990;35:1426-1430. |

| 14. | Paes FM, Kalkanis DG, Sideras PA, Serafini AN. FDG PET/CT of extranodal involvement in non-Hodgkin lymphoma and Hodgkin disease. Radiographics. 2010;30:269-291. |

| 15. | Dawson IM, Cornes JS, Morson BC. Primary malignant lymphoid tumours of the intestinal tract. Report of 37 cases with a study of factors influencing prognosis. Br J Surg. 1961;49:80-89. |

| 16. | Chadha KS, Hernandez-Ilizaliturri FJ, Javle M. Primary esophageal lymphoma: case series and review of the literature. Dig Dis Sci. 2006;51:77-83. |