Published online Jul 28, 2010. doi: 10.4329/wjr.v2.i7.257

Revised: June 7, 2010

Accepted: June 14, 2010

Published online: July 28, 2010

Transcatheter arterial embolization as treatment of upper nonvariceal gastrointestinal bleeding is increasingly being used after failed primary endoscopic treatment. The results after embolization have become better and surgery still has a high mortality. Embolization is a safe and effective procedure, but its use is has been limited because of relatively high rates of rebleeding and high mortality, both of which are associated with gastrointestinal bleeding and non-gastrointestinal related mortality causes. Transcatheter arterial embolization is a valuable minimal invasive method in the treatment of early rebleeding and does not involve a high risk of treatment associated complications. A multidisciplinary approach is necessary in the treatment of these patients and should comprise gastroenterologists, interventional radiologists, anaesthesiologists, and surgeons to achieve the best possible results.

- Citation: Andersen PE, Duvnjak S. Endovascular treatment of nonvariceal acute arterial upper gastrointestinal bleeding. World J Radiol 2010; 2(7): 257-261

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1949-8470/full/v2/i7/257.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4329/wjr.v2.i7.257

In spite of important progress in medical treatment of gastroduodenal ulcers, especially with the development of Helicobacter pylori eradication, treatment with H2-receptor-antagonists, and proton pump inhibitor therapy, acute upper gastrointestinal (UGI) nonvariceal arterial bleeding is still a severe clinical problem, often of potentially lethal character demanding fast and active intervention to control. Further, massive arterial bleeding after pancreas and bile duct surgery are also important causes of postoperative mortality[1].

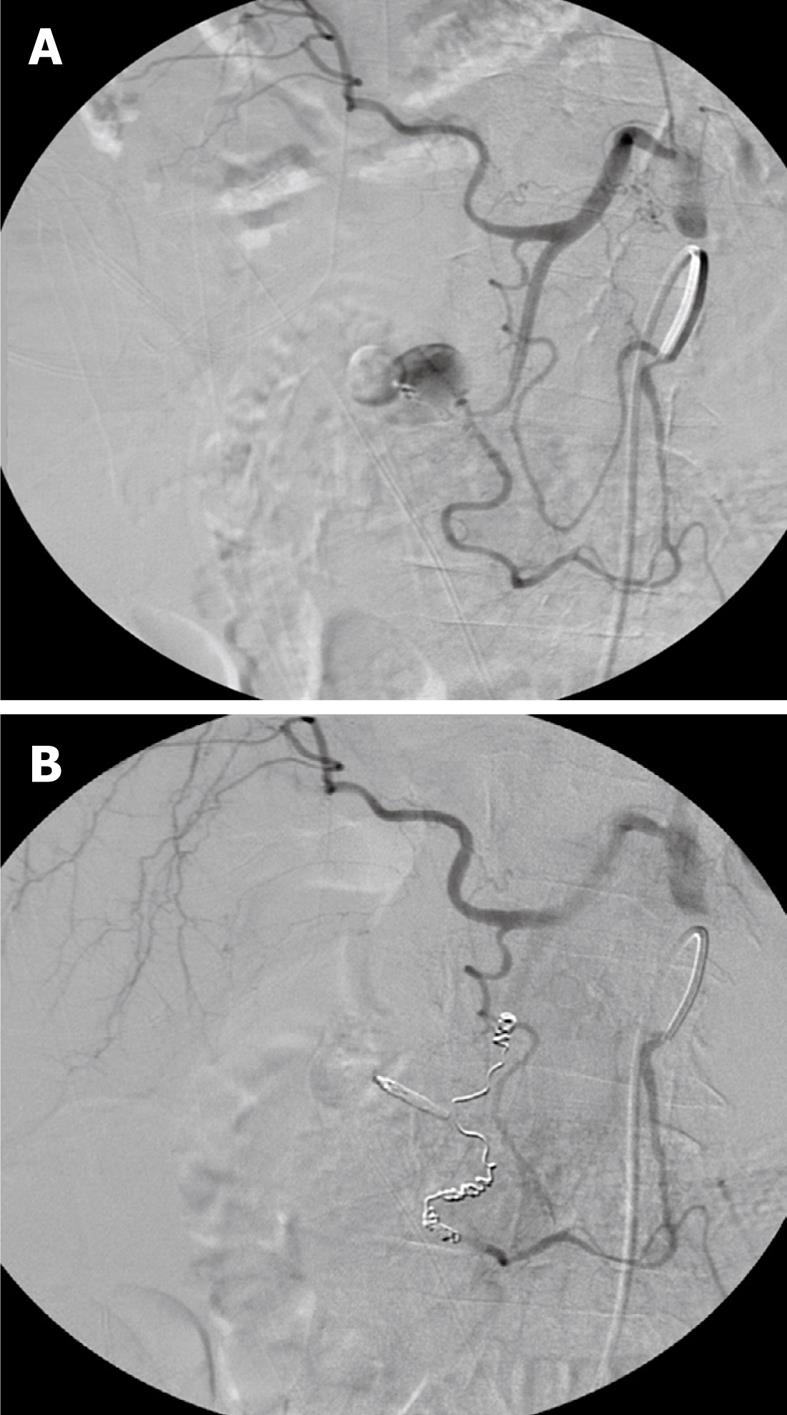

In adults with acute massive UGI bleeding the cause is duodenal ulcer in 30%-40% (Figure 1) and gastric ulcer in 20%-25%. In total, a significant mortality of 5%-15% has been unchanged during the last 30 years often related to co-morbidity[2]. In UGI bleeding endoscopy is the first line examination and treatment[3] and achieves bleeding control in up to about 95% of the patients. After primary treatment failure and recurrence of bleeding, a second endoscopic attempt, surgery or endovascular embolization should be considered[4,5]. Further, aggressive correction of coagulation disorders is very important.

In the cases where primary haemostasis without recurrence after endoscopic treatment has been achieved the mortality is less than 2%. However, in about 15% of cases endoscopy is either not available or unsuccessful [6]. Re-bleeding after primary haemostasis is seen in about 25% of cases and these patients have a mortality of about 10%. In about 5% of UGI bleeding it is not possible to stop the bleeding in the first place and in these cases the mortality is about 30%[4].

Transcatheter arterial embolization is a minimally invasive, fast, effective, and safe treatment of UGI bleeding. It has been increasingly used during recent years as it has good long term results and fewer complications than surgery.

Angiography is indicated in patients with ongoing spontaneously arising or postoperative UGI bleeding which has not been possible to control by endoscopy. Using angiography, localizing the bleeding often will be faster and more precise than surgical exploration. The sensitivity of angiography is dependent of the severity of bleeding, and is highest in haemodynamically instable patients with transfusion requirements and a bleeding of at least 1-2 mL/min before recognising the bleeding can be expected. Further, the sensitivity is dependent on the localization of the bleeding, whether the bleeding is localized or diffuse, if it is intermittent, arterial or venous, the degree of gastric and intestinal content of air, peristaltics, and patient cooperation. The sensitivity is probably no more than 50%-60%[5,7], depending on patient selection. Multislice computed tomography with reconstructions may visualise bleeding down to about 0.3 mL/min in optimal cases. If the bleeding artery cannot be visualized by contrast extravasation on angiography, CO2 angiography can be considered if available or contrast angiography after intraarterial injection of vasodilatatory medicine to provoke bleeding. Provocative angiography is not without risk of severe and difficult-to-control bleeding. If bleeding is not demonstrated, “blind” embolization can be performed on the most probable bleeding artery evaluated from endoscopy and clinical examination. A clip placed by endoscopy in the area of the bleeding may help identify the former bleeding artery if it is not actually bleeding. Further, the artery that has recently bled will often appear spastic. “Blind” embolization has a very low risk of complications but no studies have yet demonstrated the clinical effect on a long term.

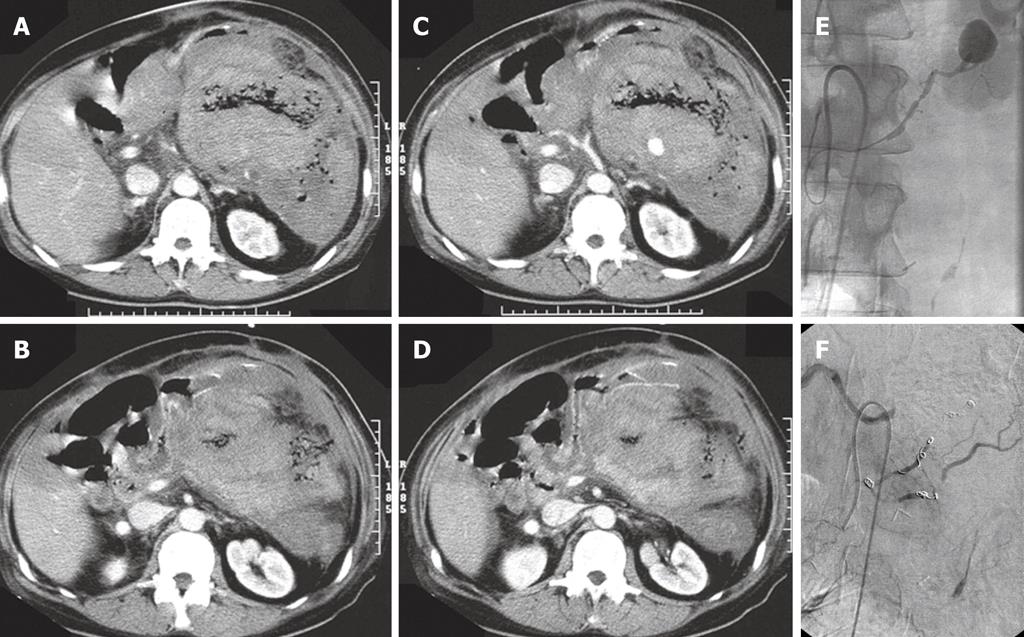

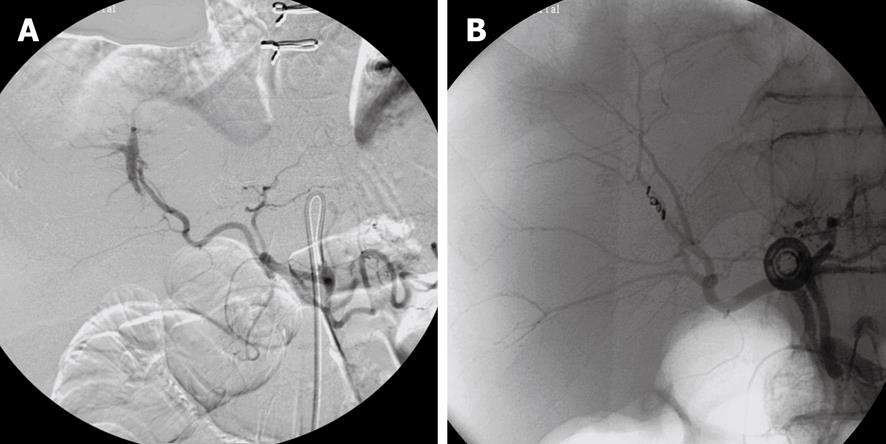

In actually bleeding arteries the localisation of the artery can often be detected very precisely and the culprit vessel catheterized accordingly and embolization performed (Figures 1, 2 and 3). Selective intraarterial local infusion of vasoconstrictive medication as treatment of UGI bleeding has been used since the 1970s but the effect was often temporary and it is no longer in general use for embolization. Not until permanent embolization methods were introduced in 1972, in the beginning with use of blood clots, the method proved of value[8]. After development of better catheterization and embolization materials, better contrast media, and advanced angiographic equipment the possibilities of embolization have increased accordingly during recent years. The results have become better and embolization as treatment has been used increasingly.

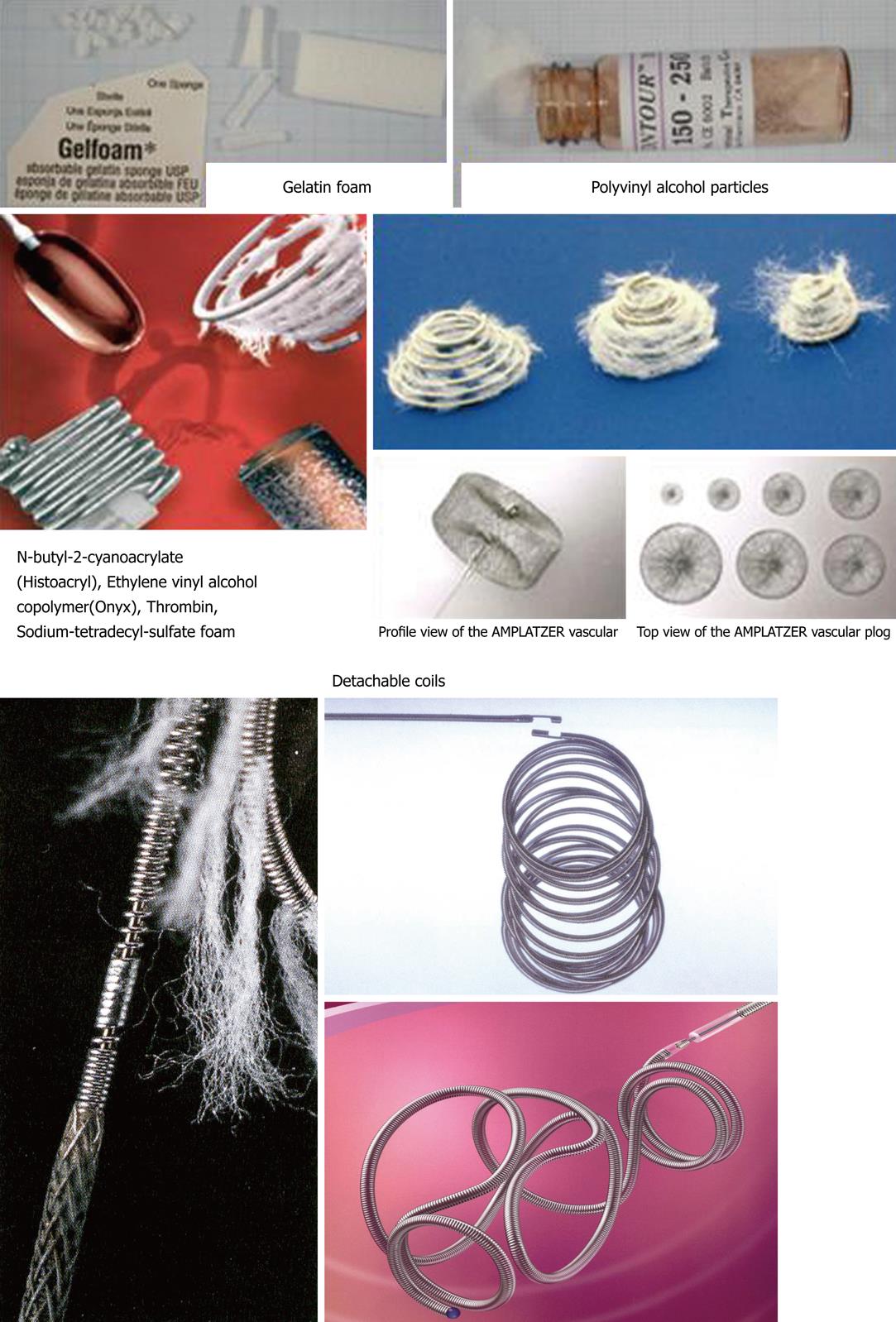

When haemostasis fails after endoscopic treatment there is a mortality of 20%-30% at surgical intervention often related to the basic disease, coagulopathy or complications related to heart, lungs or failure of more organs[9]. An alternative to surgery is endovascular embolization, which especially is indicated in surgical risk patients with competitive diseases[10]. Embolization is a minimal invasive and (super)selective treatment which is performed under local analgesia with catheterization via the femoral artery under X-ray guidance. This procedure has become safer, faster, more precise, and effective as a result of developments in technology[7,11] and is without severe complications. In most cases microcoils (Figures 1-3), gel foam or microparticles are used for embolization delivered through coaxial microcatheters (Figure 4). Microparticles are generally used for embolization of terminal branches, like in tumor vessels or distally in the intestine. They can only in selected cases be used for embolization of gastroduodenal bleeding. Gelfoam and vasopressin are cheap embolization agents but give a temporary embolization and rebleeding can be expected in some cases. Glue is difficult to handle and experience is necessary to avoid complications like sticking the microcatheter to the vessel. Onyx is rather expensive and takes up to 0.5 h or more to prepare which in acute cases might be a problem. In elective cases onyx is an option of value. Micro coils are the most commonly used embolization agents for UGI bleeding and will usually be the first line choice. They are relatively cheap and fast to deliver. They come in any size and many shapes. They give a permanent occlusion. They can be delivered by flushing with saline or by pushing with the coil pusher which also gives a better “packing” and covering of the vessel lumen. Delivery of standard coils is generally safe and precise, but detachable coils allow repositioning or exchange to another coil size or type before final delivery, and thus are even more safe and precise in use. They are to be preferred if the delivery microcatheter is in an unstable position. They are, however, rather expensive. There are no studies comparing the different embolization methods and thus no evidence which is to be recommended. It will most often come down to which method and materials each person is most used to and comfortable with.

Embolization is an effective treatment with good long term results. Technical success can, in experienced hands, be achieved in 90%-98% of cases[6], but about 10% will have rebleeding within 3 d[12]. Primary clinical success with haemostasis in the group of patients with technically successful embolization is about 80%[6] and secondary clinical success after reembolization is achieved in more than 80%[9]. Lethal early rebleeding is seen in 2%-3% of cases. Clinical success without rebleeding after 30 d is achieved in UGI bleeding in 65%-68% of cases. Total mortality after long-term follow-up is about 25%[13].

It is important to know the vascular anatomy and its normal variations[14]. Both distal and proximal to the bleeding part of the vessel (the front- and backdoor) should be closed by embolization. If dual supply to the bleeding area is present, both arterial sources must be embolized. Anastomoses from the superior mesenteric artery are not uncommon, and it is often necessary to embolize both anterior and posterior gastroduodenal artery arcades, right gastroepiploic or superior pancreaticoduodenal arteries.

Patients who have undergone a clinically successful embolization have 13 times higher probability of survival than those who have had a failed procedure. The prognosis is, however, poorer for patients with multiorgan failure independent of the outcome of the embolization. Thus, embolization has a significant positive effect on survival independent of the clinical condition, and aggressive treatment with embolization is recommended in patients with acute non-varicous UGI bleeding[15].

Embolization is a safe procedure in patients with non-varicous UGI bleeding, and the number of complications is very low and most often transient in relation to the treatment (5%)[6,9]. The described complications include access-site complications, dissection of the target vessel, hepatic or splenic infarction, and duodenal stenosis. A few cases of intestinal ischaemia and necroses have also been described after embolization.

There are no available randomized, prospective studies comparing surgery with embolization for treatment of UGI bleeding. A retrospective analysis of the results after embolization and surgical treatment in patients with UGI bleeding where endoscopic therapy had failed in 70 patients (31 embolotherapy and 39 surgery) showed no significant difference regarding length of admission, recurrence of bleeding (about 25%), need of further surgical intervention (about 20%), transfusion before or after treatment, or mortality (about 22%)[16]. Both groups of patients were comparable, although the patients in the group of embolized patients were a little older and also had more cardiac diseases.

Multidisciplinary cooperation between gastroenterologists, interventional radiologists, surgeons, and anaesthesiologists is important in the treatment of UGI bleeding. Logistics are optimal with an interventional radiological team on call any time.

Transcatheter arterial embolization is a safe alternative to surgery for massive UGI bleeding that is refractory to endoscopic treatment. It can be performed with high technical and clinical success rates, and should be considered the salvage treatment of choice in patients, especially those at high surgical risk. In many institutions transcatheter arterial embolization is considered as the first-line intervention for massive UGI bleeding after failed endoscopic treatment[10,17].

Peer reviewers: Roberto Miraglia, MD, Department of Diagnostic and Interventional Radiology, Mediterranean Institute for Transplantation and Advanced Specialized Therapies (IsMeTT), Via Tricomi 1, Palermo, 90100, Italy; Adjunct Associate Professor of Radiology, University of Pittsburgh, PA 15260, United States; Takao Hiraki, MD, Radiology, Okayama University Medical School, 3-5-1 Shikatacho, Okayama 700-0861, Japan; Ender Uysal, MD, Sisli Etfal Training and Research Hospital, Clinic of Radiology, Sisli Etfal Eğitim ve Araştırma Hastanesi Radyoloji Kliniği, Etfal sok. Sisli, Istanbul 34377, Turkey

S- Editor Cheng JX L- Editor O’Neill M E- Editor Zheng XM

| 1. | de Castro SM, Kuhlmann KF, Busch OR, van Delden OM, Laméris JS, van Gulik TM, Obertop H, Gouma DJ. Delayed massive hemorrhage after pancreatic and biliary surgery: embolization or surgery? Ann Surg. 2005;241:85-91. |

| 2. | Rollhauser C, Fleischer DE. Nonvariceal upper gastrointestinal bleeding: an update. Endoscopy. 1997;29:91-105. |

| 3. | Barkun A, Fallone CA, Chiba N, Fishman M, Flook N, Martin J, Rostom A, Taylor A. A Canadian clinical practice algorithm for the management of patients with nonvariceal upper gastrointestinal bleeding. Can J Gastroenterol. 2004;18:605-609. |

| 4. | Blocksom JM, Tokioka S, Sugawa C. Current therapy for nonvariceal upper gastrointestinal bleeding. Surg Endosc. 2004;18:186-192. |

| 5. | Bonacker MJ, Begemann PG, Dieckmann C, Yekebas E, Adam G. [The role of angiography in the diagnosis and therapy of gastrointestinal hemorrhage]. Rofo. 2003;175:524-531. |

| 6. | Loffroy R, Guiu B. Role of transcatheter arterial embolization for massive bleeding from gastroduodenal ulcers. World J Gastroenterol. 2009;15:5889-5897. |

| 7. | Lefkovitz Z, Cappell MS, Lookstein R, Mitty HA, Gerard PS. Radiologic diagnosis and treatment of gastrointestinal hemorrhage and ischemia. Med Clin North Am. 2002;86:1357-1399. |

| 8. | Rösch J, Dotter CT, Brown MJ. Selective arterial embolization. A new method for control of acute gastrointestinal bleeding. Radiology. 1972;102:303-306. |

| 9. | Aina R, Oliva VL, Therasse E, Perreault P, Bui BT, Dufresne MP, Soulez G. Arterial embolotherapy for upper gastrointestinal hemorrhage: outcome assessment. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2001;12:195-200. |

| 10. | Loffroy R, Guiu B, Cercueil JP, Lepage C, Latournerie M, Hillon P, Rat P, Ricolfi F, Krausé D. Refractory bleeding from gastroduodenal ulcers: arterial embolization in high-operative-risk patients. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2008;42:361-367. |

| 11. | Funaki B. Endovascular intervention for the treatment of acute arterial gastrointestinal hemorrhage. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 2002;31:701-713. |

| 12. | Duvnjak S, Andersen PE. The effect of transcatheter arterial embolisation for nonvariceal upper gastrointestinal bleeding. Dan Med Bull. 2010;57:A4138. |

| 13. | Defreyne L, Vanlangenhove P, De Vos M, Pattyn P, Van Maele G, Decruyenaere J, Troisi R, Kunnen M. Embolization as a first approach with endoscopically unmanageable acute nonvariceal gastrointestinal hemorrhage. Radiology. 2001;218:739-748. |

| 14. | Uflacker R. Atlas of vascular anatomy: an angiographic approach. Baltimore: Williams & Wilkins 1997; . |

| 15. | Schenker MP, Duszak R Jr, Soulen MC, Smith KP, Baum RA, Cope C, Freiman DB, Roberts DA, Shlansky-Goldberg RD. Upper gastrointestinal hemorrhage and transcatheter embolotherapy: clinical and technical factors impacting success and survival. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2001;12:1263-1271. |

| 16. | Ripoll C, Bañares R, Beceiro I, Menchén P, Catalina MV, Echenagusia A, Turegano F. Comparison of transcatheter arterial embolization and surgery for treatment of bleeding peptic ulcer after endoscopic treatment failure. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2004;15:447-450. |