BONY STRUCTURES IN THE HEAD AND NECK

Most bony lesions of the skull are benign tumors. They are mainly bone tumors and tumor-like lesions. With the exception of osteomas of the paranasal sinuses and exostosis of the external auditory canal, these lesions occur rarely. Osteomas and exostosis of the external auditory canal are mostly incidental findings with computed tomography (CT). Due to its location close to the tympanic membrane, exostosis can be easily differentiated from osteoma, which is located more laterally. If only magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is performed, a compact osteoma in an air-filled cavity, as well as exostosis, cannot be proven due to the absence of a signal[1].

Fibrous dysplasia with bony lesions can be documented by MRI with low signal intensity in the T2-weighted sequences. Therefore, CT should be performed afterwards. Due to its high uptake of contrast medium, fibrous dysplasia is often falsely diagnosed as a malignant tumor[2].

Chordomas are the most common primary malignant tumors of the skull base[3]. They are mostly located at the clivus[4]. CT shows lobulated, sharply restricted osteolysis. In T2-weighted sequences, they appear with a high intensity and high contrast enhancement[5]. In numerous cases, chordomas can be mistaken for chondrosarcomas, which are cartilage-producing tumors. Chondrosarcomas most commonly appear in the petro-occipital fissure and clivus, and rare cases of chondrosarcoma are found in the temporomandibular joint[6]. Chondrosarcomas show the same T2-weighted images as chondromas. In these cases, biopsy is necessary[7].

Solitary and multiple metastases at the skull base are more common than primary malignant tumors. Thus, CT or a whole body scan with 18-fluoro-2-deoxy-D-glucose (FDG) positron emission tomography (PET) is performed regarding tumor staging, especially in breast cancer[8], renal cell carcinoma, and lung cancer[9].

Traumatic lesions offer a wide range of injuries. Emergency examinations allow a very short time frame to start the treatment before causing permanent damage or death. For that reason, the first choice of examination should be CT, with its short examination time.

The advantage of three-dimensional reconstruction in emergency patients with skull-base fractures using solid and transparent volume-rendering techniques and maximum intensity projection (MIP) has been examined by Ringl et al[10]. They have ascertained that MIP with regard to sensitivity (P = 0.9) visualizes fractures slightly better than high resolution multiplanar reformation (HR-MPR). Due to the relatively low detection rate using HR-MPR alone, it has been recommended to read MIP reconstructions in addition to the obligatory HR-MPRs to improve fracture detection[11].

NERVOUS SYSTEM

The differentiation between benign and malignant tumors is one of the most important challenges. For that reason, it is necessary to evaluate infiltration of bony structures, especially in neurovascular tumors.

Multidetector CT (MDCT), with its soft tissue and bone window setting, is a good option. The application of non-ionic, iodine-based contrast medium enhances the sensitivity of the image of the lesion[12].

MRI is useful for imaging the nervous system. Therefore axial and coronal sequences with an array of 512 or 1024 pixels are performed. The slices should not be thicker than 3 mm. It is important that the MRI images the whole pathology[13].

Basically, axial T2-weighted sequences are performed to get an overview. Afterwards coronal and axial high-resolution T1-weighted sequences are performed before and after contrast application. In order to increase the outline of the lesion, fat-suppressed sequences can be added[14].

Diffusion tensor tractography (DTT) using 3 tesla (3T) MRI is an upcoming innovation. DTT facilitates the imagination of neural fibers with 3T MRI. Akter et al[15] have compared the results of DTT with surgery and have found agreement.

MUCOUS MEMBRANES AND SQUAMOUS EPITHELIUM

Due to its availability MDCT is a frequently used method[16]. The view of the nasopharynx and oropharynx should be parallel to the hard palate, and the view of the hypopharynx and larynx parallel to the vocal cords. The examined area reaches from the skull base to the height of the manubrium of the sternum[17]. Furthermore, the application of non-ionic, iodine-based contrast medium is mandatory in order to differentiate the pathology more clearly. Axial MDCT is performed in a soft tissue window setting (minimal slice thickness 2-3 mm) and in a bone window setting (minimal slice thickness 1-2 mm)[18]. Moreover, sagittal and coronary reconstructions provide a clearer depiction of the pathology. Finally, MDCT provides accurate imaging of the spreading of tumor masses due to higher contrast uptake, as well as infiltration of the muscle or fat tissue[19].

In comparison to MDCT, MRI is the preferable method in soft tissue imaging and provides a good topographic relationship to the anatomical structures. The drawbacks are long examination times (30-40 min) and the necessity for patient compliance.

The most common inflammations in the head and neck are sinusitis and inflammation of the inner ear. Unenhanced CT is the gold standard to examine the sinuses or the inner ear. The advantage of CT is the possibility of three-dimensional reconstructions[20]. To verify chronic sinusitis, CT of the paranasal sinuses should be performed[21]. The images illustrate mucosal swelling, whereas acute sinusitis additionally shows air-fluid level[21].

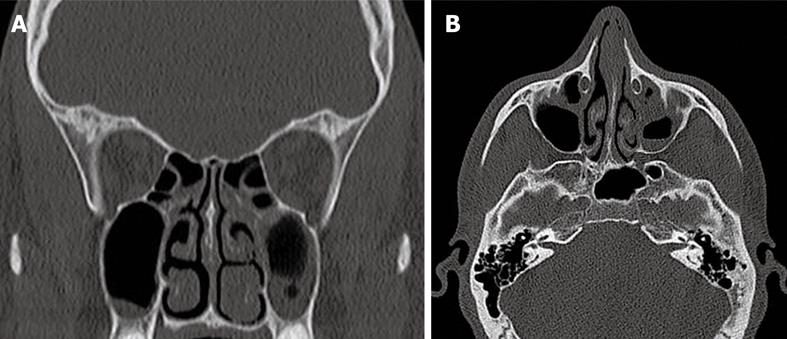

A new upcoming technique in the CT area is Flash CT. It could gain importance in the near future, for example, for imaging the sinuses, because the radiation dose for patients is reduced and the examination time is shortened. However, the patients should be slim in order to obtain proper images (Figure 1).

Figure 1 Chronic sinusitis, especially in the left maxillary sinus.

A: SOMATOM Definition Flash coronal reconstruction; B: SOMATOM Definition Flash computed tomography axial layer.

Examinations of the middle ear are usually performed with spiral CT of the petrous portion of the temporal bone. Features that are revealed by CT are thickening of the tympanic membrane and fluid in the middle ear[22].

In the case of recurrent cholesteatoma, diffusion-weighted MRI shows a positive predictive value; however, CT still remains the gold standard[23]. Plouin-Gaudon et al[24] have concluded that, in cases of doubtful CT, diffusion-weighted MRI can confirm recurrence or avoid second-look surgery.

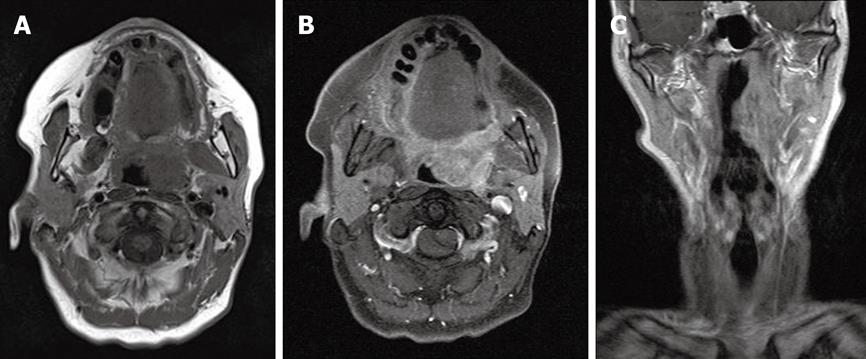

Several sequences should be performed as: (1) axial T2-weighted fat-suppressed sequences; (2) axial T1-weighted spin-echo-sequences before and after contrast application with a slice thickness of 2-3 mm; and (3) coronary and sagittal T1-weighted spin-echo sequences after contrast application with fat suppression in 256 × 256 pixels[18,19] (Figure 2).

Figure 2 Palatine tonsil carcinoma on the left side.

A: MRT T2-weighted axial layer; B: MRT T1-weighted axial layer; C: MRT T1-weighted coronal layer.

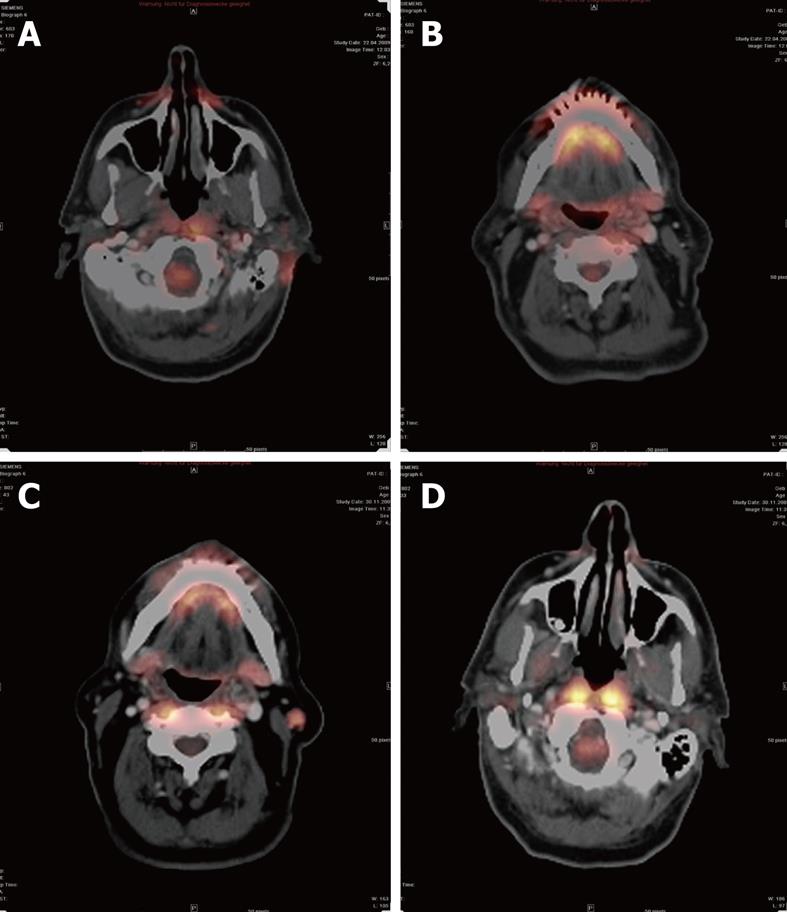

In the case of recurrent tumors, FDG-PET can be performed. This technique has a high sensitivity for detection of recurrent tumors, which depends on FDG uptake[25,26]. The higher metabolism of glucose in malignant cells and inflammatory tissues can be documented. A disadvantage of this method is that inflammatory tissue, for example, after radiotherapy, and malignant tissue have a higher FDG uptake. For that reason, a PET scan should be performed 2-4 mo after therapy, at the earliest[27] (Figure 3).

Figure 3 Positron emission tomography-CT after resection of a melanocytic tumor of uncertain malignant origin.

A: The resection area still showed a higher glucose metabolism than normal healthy tissue at 2 mo after therapy; B: A small lymph node (LN), but no sign of higher metabolism; C: A malignant LN with higher metabolism; D: There was no higher glucose metabolism noticeable at 6 mo after therapy.

GLANDULAR TISSUE

Salivary glands

The most common malignancy of the parotid gland is mucoepidermoid carcinoma[28,29]. In the submandibular gland, pleomorphic adenomas remain the most common benign tumor[30]. The same diagnoses prevail in the sublingual and minor salivary glands, where malignancies outnumber benign tumors[31].

Some would advocate the use of MRI as the best technique to evaluate a neoplasm of the major salivary glands. Implicit in such a decision is that the clinicians are highly confident that the process in the gland is neoplastic and not obstructive or inflammatory. If the mass is considered to be related to sialolithiasis, CT should be recommended first, because MRI is not as reliable in detecting small calculi. If the lesion is suspected to be neoplastic, MRI should be preferred over other modalities, as nearly all parotid lesions are well visualized on T1-weighted MRI because of the hyperintense background of the gland[32]. The T1-weighted image provides an excellent assessment of the tumor margin, its extent, and its pattern of infiltration. This sequence, coupled with fat suppression and contrast-enhanced T1-weighted imaging, which is primarily used to address perineural spread, bone invasion, or meningeal infiltration, is the best means for documenting tumor spread[33,34]. On fat-suppressed images, the bony structures and the skull base are hypointense. Enhancing tissue extending into this hypointense background is indicative of bone invasion. If it is likely to be a nervous infiltration, MRI is usually the method of choice. In cases of meningeal symptoms, MRI is preferred because the leptomeninges are better illustrated with MRI than with CT[35]. T2-weighted MRI has been shown to be a reasonably reliable predictor regarding malignancy or benignity of a salivary gland tumor[36]. In general, however, the most common benign tumor of the salivary glands, pleomorphic adenoma, has very high signal intensity on T2-weighted images[37]. The value of contrast enhancement also applies to CT, as the attenuation of the cyst is not comparable to that of pure fluid. Berg et al[38] have reckoned that CT attenuation of masses, other than for differentiating benign cysts from solid masses, and lipomas from other neoplasms, does not replace histological diagnosis, because most malignant and non-malignant solid masses have similar CT attenuation. Malignancies tend to have irregular infiltration into the glandular parenchyma, which can be detected with MRI and CT, therefore, there are some exceptions that CT has sufficient accuracy to predict the histological diagnosis of a lesion. CT is less precise than MRI for determining the extent of disease, therefore, there is little reason to perform CT rather than MRI for suspected salivary gland masses[39].

Nakamura et al[40] have evaluated various physiological FDG accumulations in the head and neck, and have compared them with tumor FDG accumulation, and have come to the conclusion that tonsil, extraocular muscle, and sublingual glands show a relatively high FDG accumulation, which is sometimes similar to tumor accumulation. The right-to-left ratio of standardized uptake value (SUVmax) is useful in differentiating tumor from physiological accumulation, and the presence of tumor might be highly suspected in cases with a ratio of ≥ 1.5.

Ultrasound is also mentioned in the literature as one of the first choices in imaging the salivary glands[41,42]. The advantage of this examination mode is the combination of fine needle aspiration cytology with its ability to differentiate between benign and malignant lesions[43].

Thyroid gland

Thyroid nodules irrespective of their malignancy or benignity are sometimes found incidentally during other examinations such as thoracic CT. The gold standard in the literature is doubtless ultrasound; mostly due to its availability and low costs[44].

As already mentioned above, ultrasound can be used to guide invasive procedures such as biopsy, and to visualize moving features such as blood vessels, the esophagus, and blood flow. Another advantage is that there is no radiation like in a CT.

In patients, who suffer from hyperthyrosis CT with contrast medium is only possible if the patient has been prepared with sodium perchlorate, because the contrast medium contains iodine, which might result in a thyrotoxic crisis. MRI of the thyroid gland is possible and shows nodular non-homogeneity as well as contrast enhancement, but is rarely performed in daily routine; mostly due to its high costs and long examination times.

Lymphatic tissue

Increased lymph node (LN) size is usually palpated by patients themselves. The gold standard for suspicious LNs is ultrasound. If there are more pathologically increased LNs or a primary tumor is noted, CT is the better choice to detect all increased LNs and follow-up is easier, in comparison with ultrasound, because the latter is highly dependent on the examiner.

Blood vessels

MDCT, dynamic CT angiography (CTA), high-field MRI, four-dimensional MR angiography (MRA) are recent improvements in imaging arteries. These techniques form the basis for planning further investigations[45].

In emergency examination, CTA is a state-of-the-art technique, whereas contrast-enhanced MRA is the technique that is recommended in the literature. In cases of acute stroke, diagnosis has to be made as quickly as possible. Damage detection at 24-48 h after onset of symptoms is not always possible. Therefore, Totaro et al[45] have concluded that diffusion-weighted imaging in the post-acute phase of cerebral ischemia in patients in whom CT did not yield a definite diagnosis could be the solution[10].

MRA, with its improvements in parallel imaging at high-field strength, with resultant high-spatial-resolution data acquisition over large fields of view has become an interesting alternative to the traditional catheter-directed selective angiography[46]. This technique allows preoperative noninvasive identification of stenosis and restenosis and detection of intracranial aneurysms[47].

A further new topic is the role of selective intra-arterial, catheter-directed chemotherapy for head and neck cancer. In these cases, pre-interventional MRA is profitable for imaging tumor-feeding vessels, anatomical structures[48] and the caliber of the vessels[49].

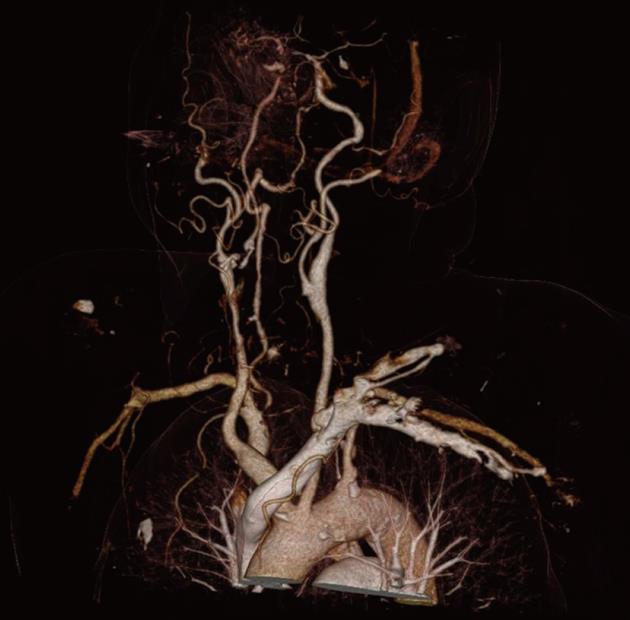

MRA is the best way to avoid a primary surgical operation. Moreover, the anatomical structures, as well as the vascularization, can be illustrated. The vascularization is important in embolizing head and neck tumors before starting the intervention. One of the most promising upcoming innovations is dual-energy CTA (DE-CTA). The possibility of suppressing the bones and providing three-dimensional vascular models for the attending doctor makes DE-CTA of the carotid arteries an attractive alternative to MRA[50]. The bone removal speeds up the imaging analysis, although, due to the slightly limited specificity and segmentation error, each case should be double checked on the original images[51] (Figures 4 and 5). In emergency patients with suspected arterial injury in the head and neck, MDCT angiography should be performed as standard[52].

Figure 4 Flash CT dual-energy bone removal head collection showing the carotid arteries.

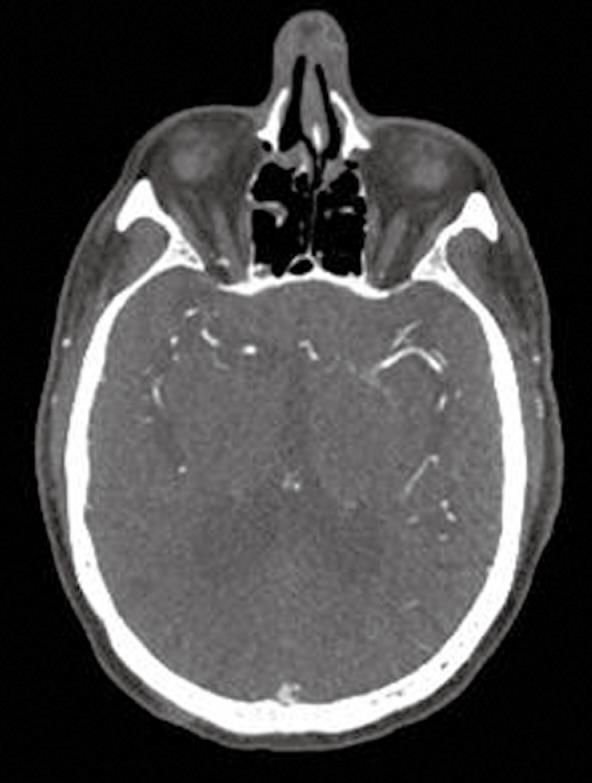

Figure 5 Definition Flash-CT showing the cerebral arteries.

A new upcoming technique is dual-energy CT, with its possibility of bone removal and three-dimensional reconstructions, which provides excellent images. Nevertheless there are disadvantages such as material artifacts of metal and segmentation errors.

CONCLUSION

Currently, various options are available for head and neck imaging. To decide on the best method in each case, the examination method has to be illuminated more precisely, because CT, MRI, PET-CT and ultrasound each have their advantages and disadvantages. It is important to decide which structure in the examined area is affected in order to find the most suitable method. The advantages of CT compared to MRI are its availability, short examination time, and its detailed imaging of bony structures, inflammatory lesions and acute vascular lesions. The disadvantages are the worse soft tissue imaging, although contrast application improves the quality. MRI is the better choice for imaging soft tissue but its disadvantages are long examination times and the necessity for patient compliance. For imaging the nervous system and salivary glands, MRI is more useful than CT unless infiltration of the bone or calcification in the gland is assumed. In such cases, CT should be performed afterwards. PET-CT in diagnosing recurrent tumors utilizes the high glucose uptake of tumors to visualize the tumor. The negative aspect is the high metabolism of inflammatory tissue in comparison to healthy tissue, which can lead to incorrect diagnosis of malignancy. Ultrasound benefits from its availability and low costs, as well as from the short examination time but it is considerably dependent on the examiner. Finally, there are many new upcoming techniques in the CT field, such as dual-energy CT and Flash CT, and in the MRI field, such as MRA, spectroscopy and tractography. Each new technique has its particular advantages. Flash CT could gain importance in the near future because the radiation dose for patients is reduced and the examination time is shortened in comparison to standard CT scanning. Dual-energy CT, with its possibility of bone removal and three-dimensional reconstruction, provides excellent images. Nevertheless there are disadvantages such as material artifacts of metal and segmentation errors. DTT using 3T MRI is one of the most recent techniques in imaging neural fibers. In conclusion, new techniques are increasingly becoming available, and it is important to choose the right examination procedure for each medical question.

Peer reviewers: Patrick K Ha, MD, Assistant Professor, Johns Hopkins Department of Otolaryngology, Johns Hopkins Head and Neck Surgery at GBMC, 1550 Orleans Street, David H Koch Cancer Research Building, Room 5M06, Baltimore, MD 21231, United States; Alexander D Rapidis, MD, DDS, PhD, FACS, Professor, Chairman, Department of Head and Neck/Maxillofacial Surgery, Greek Anticancer Institute, Saint Savvas Hospital, 171 Alexandras Avenue, 115 22 Athens, Greece

S- Editor Cheng JX L- Editor Kerr C E- Editor Zheng XM