INTRODUCTION

Mitral annular calcification (MAC) is a commonly encountered phenomenon, and is one of the most common findings in the heart in autopsy series[1]. A variant of this entity is caseous MAC, in which an ovoid, focal mass is found with internal, caseous fluid-like calcifications and debris[2]. Caseous MAC contains a mixture of calcium, salts, fatty acids, and cholesterol and results in a soft mass in the mitral annulus[3]. Although caseous MAC can be definitively diagnosed by its imaging features and by its classic location, it may present a diagnostic dilemma. Several reports have described the misdiagnosis of caseous MAC as a cardiac neoplasm or as an abscess, resulting in unnecessary surgery[4-6].

Herein, we report 3 patients in whom a diagnosis of caseous MAC was ultimately made. These cases and the associated images demonstrate the characteristic appearance of caseous MAC, and the features of this entity that differentiate it from other cardiac masses which it may mimic.

CASE REPORT

Case 1

A 63-year-old male with a T3N2M0 sigmoid cancer underwent surgical resection and subsequent post-operative chemotherapy. The patient had a series of non-cardiac, non-gated contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CT) scans of his chest, abdomen, and pelvis performed for staging of his sigmoid cancer. During the patient’s third restaging CT scan, an ovoid structure was detected at the aorto-atrial septum (Figure 1). Review of the two prior restaging CT studies in this patient also showed this finding to be present, upon retrospective evaluation. The mass had central, homogeneous hyperattenuation, liquefied calcium, with a shell-like, peripheral, calcified rim. This mass was noted to be present and stable on two subsequent CT scans. A presumptive diagnosis of caseous MAC was made. Because of the characteristic appearance of the mass, further diagnostic studies were not pursued.

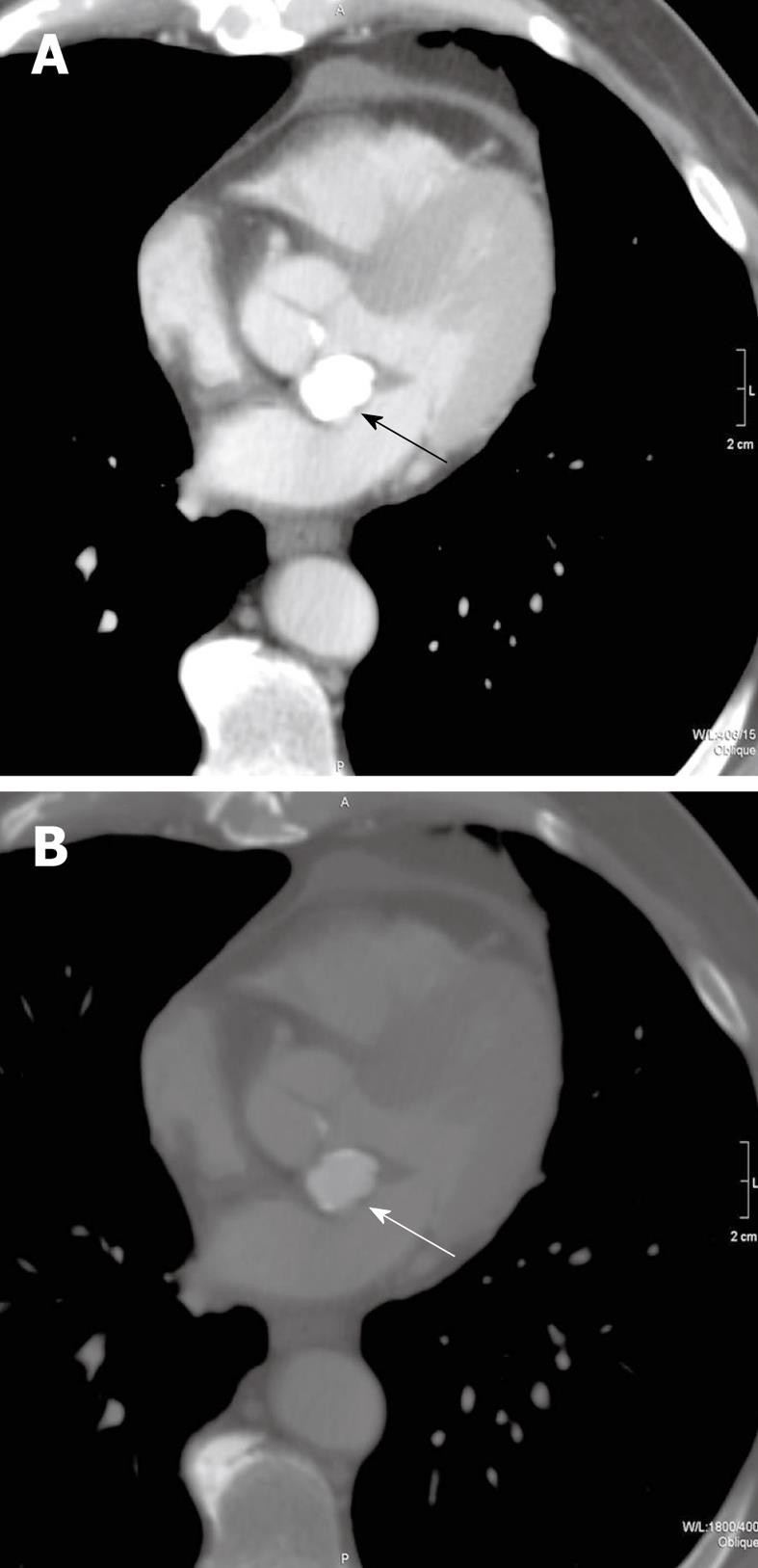

Figure 1 Transverse, non-gated, post-contrast CT images at a level through the heart with mediastinal (A) and bone (B) windows and level settings shown (kVp = 120, mAs = 214, DFOV = 314 mm).

Caseous mitral annular calcifications are noted in the aorto-atrial septum (arrows). On the mediastinal window and level settings, the mass shows homogeneous hyperattenuation which cannot be differentiated from other calcific structures. When the window and level settings are adjusted, there is a rim of peripheral calcification with central, homogeneous hyperattenuation. This mass was stable in comparison to CT scans before and after this study (not shown).

Case 2

This patient was an 84-year-old Hispanic female admitted to the hospital for nausea and vomiting, with a history of Type II diabetes mellitus, dyslipidemia, hypertension, peripheral vascular disease, dementia, asthma, and hypothyroidism. She also had a long-standing history of dyspnea on exertion. On cardiac exam, the patient had an S4 gallop and a grade 4/6 systolic murmur at the left sternal border. The admission chest radiograph showed a 2.5 cm nodule overlying the cardiac silhouette, which was initially incorrectly interpreted as being within the lung (Figure 2). Echocardiogram (Figure 3) showed mild enlargement of the left atrium, and mild concentric hypertrophy of the left ventricle with normal function. The mitral valve annulus on echocardiogram showed an ovoid mass which was peripherally echogenic and centrally less so. The echocardiogram also demonstrated mild mitral regurgitation. To further clarify the nature of the potential lung nodule, the patient had a chest CT scan with contrast (Figure 4). From review of the CT scan and correlation with prior chest radiographs, it was concluded that caseous MAC were present and the likely reason for the radiographically apparent nodule.

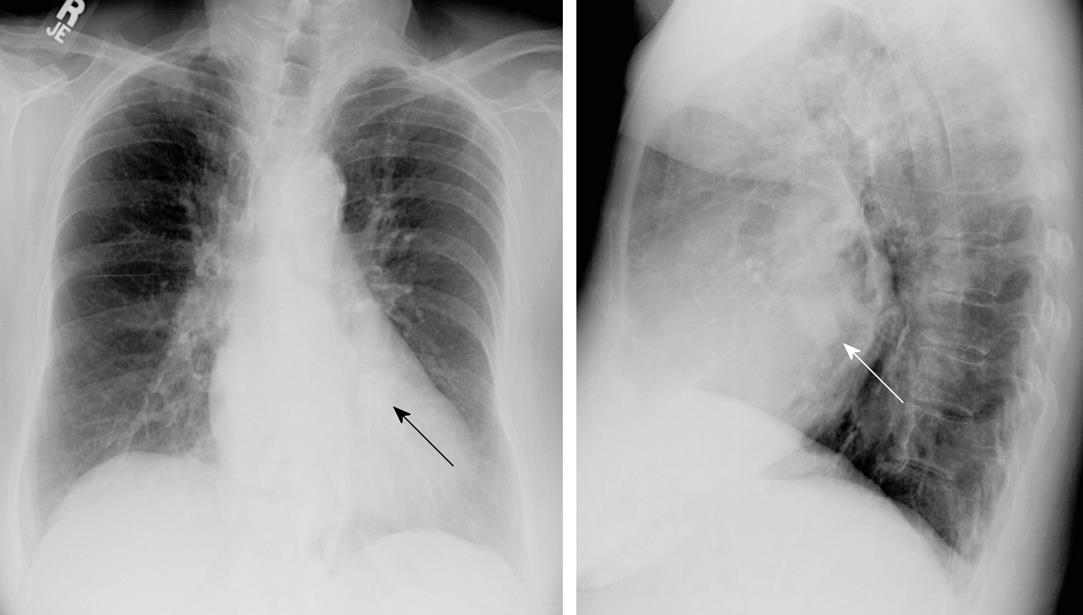

Figure 2 P-A (left) and lateral (right) views of the chest demonstrate an ovoid nodule overlying the cardiac silhouette on both views (arrows).

This was misinterpreted as a possible pulmonary nodule. On plain radiography, its nature is difficult to delineate.

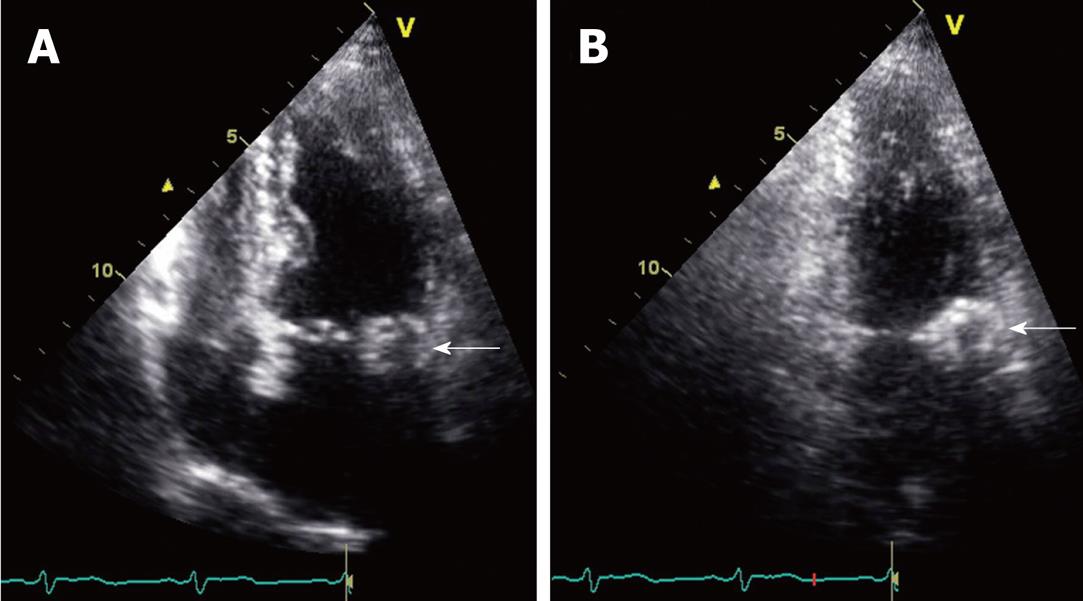

Figure 3 Slightly oblique four-chamber (A) and two-chamber (B) still frame images are obtained from an echocardiogram.

These views demonstrate a mass along the mitral annulus (white arrows). The caseous mitral annular calcifications are seen as an ovoid mass. A difference between the relatively echolucent center and the more echogenic periphery of this structure is perceptible. This is consistent with the centrally liquefied calcium and the peripheral more dense calcium observed on other modalities.

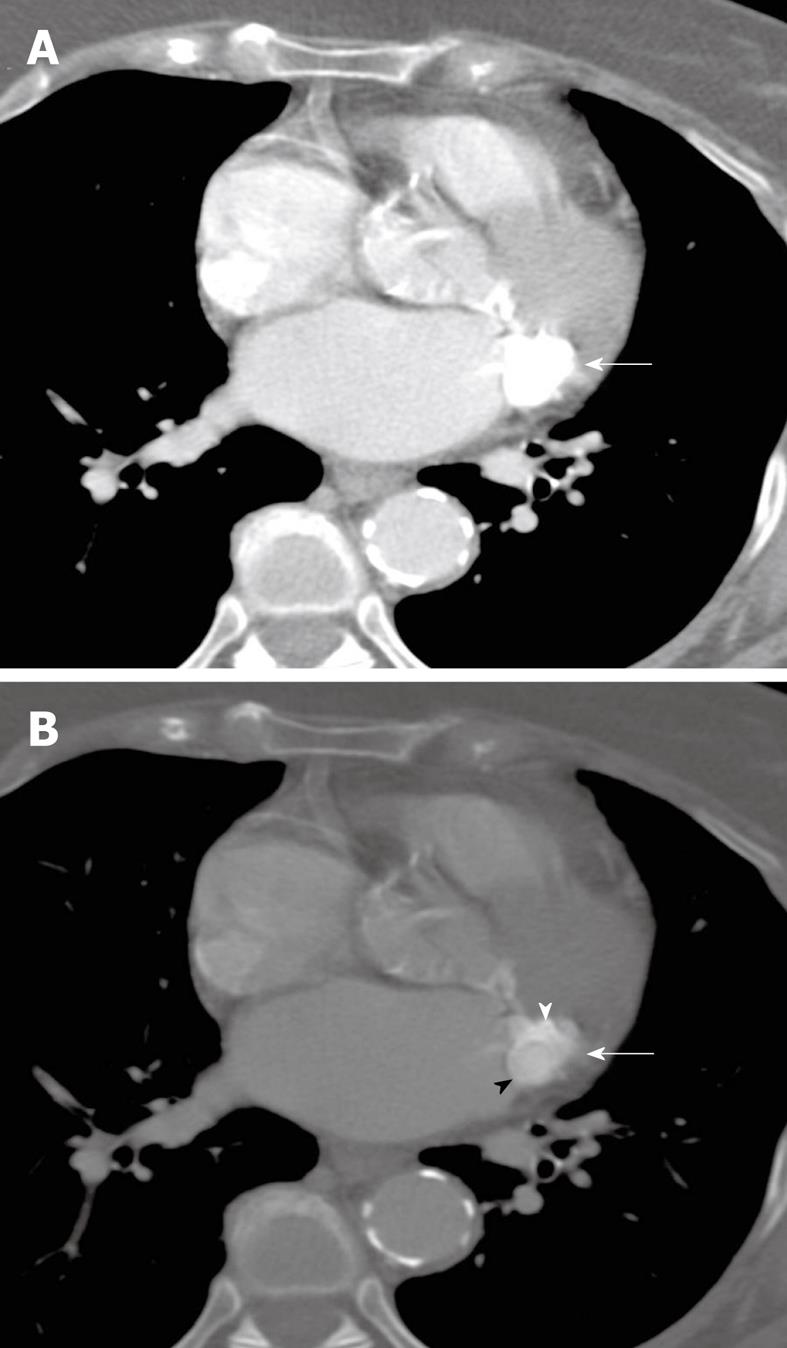

Figure 4 Transverse, non-gated, post-contrast CT images at a level through the heart are shown with mediastinal (A) and bone (B) windows and level settings (kVp = 120, mAs = 220, DFOV = 310 mm).

An ovoid mass of caseous mitral annular calcifications is seen high along the posterior portion of the mitral annular leaflet (white arrows). Although there is motion artifact, there is differing attenuation between the calcific rim of this structure (white arrowhead) and the central homogeneous liquefied calcium, which is slightly less hyperattenuating (black arrowhead). This difference is seen on the bone window image (B), but is not demonstrable on the mediastinal window/level settings (A). Based on correlation with the scout view (not shown), this was felt to be the cause of the nodule seen on plain radiography (Figure 3).

Case 3

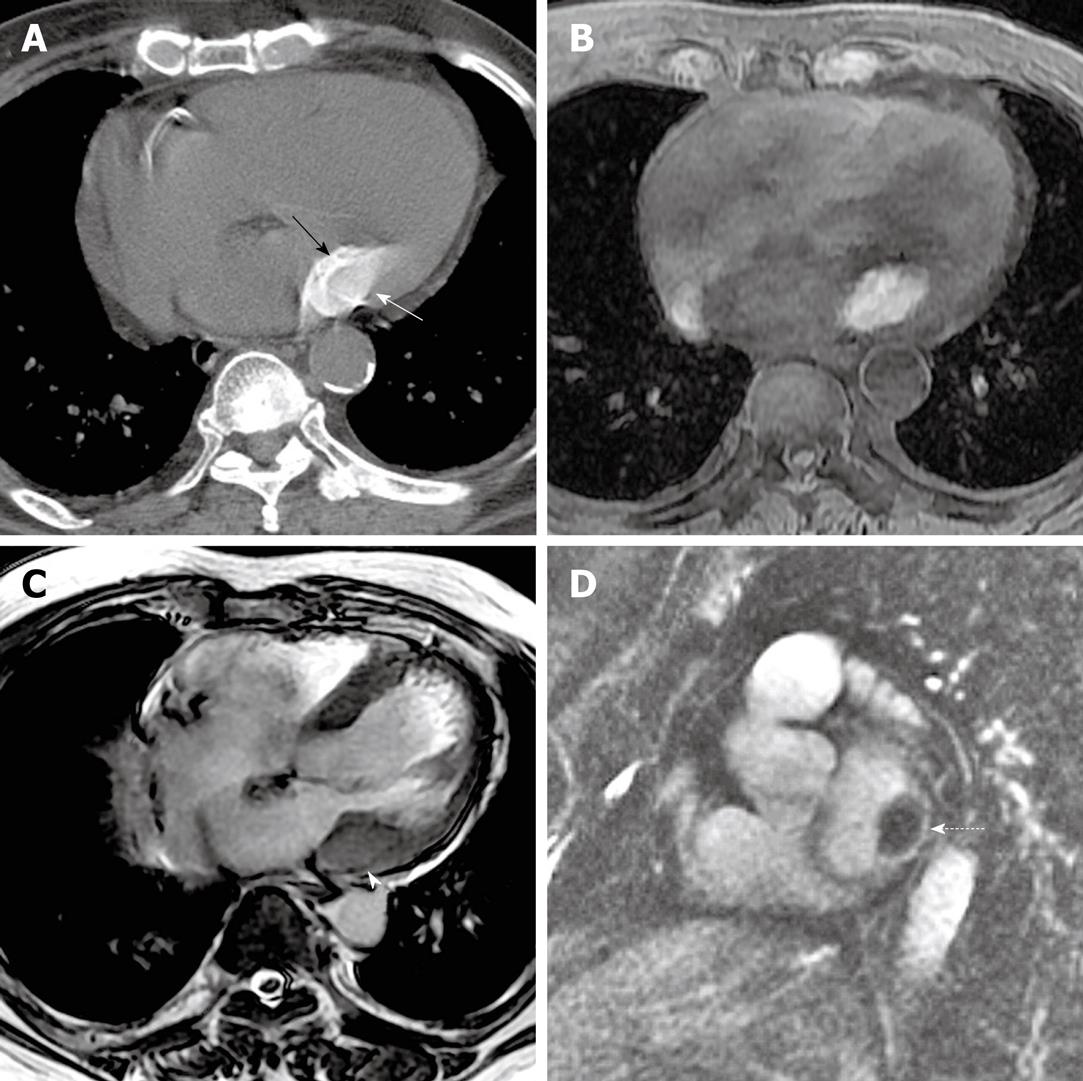

An 82-year-old male presented with mild, progressive dyspnea on exertion. A chest radiograph performed at an outside institution was unavailable, but was unremarkable by report. An echocardiogram, also performed at an outside institution, by report demonstrated a hypoechoic mass along the posterior annulus with some echogenic components, which was felt to represent a possible myxoma with calcifications. Cardiac magnetic resonance imaging (CMR) was performed. Cine balanced steady state free precession sequences demonstrated focal prominence of the posterolateral wall of the left ventricle. Further sequences demonstrated an ovoid mass with low signal on T2, but bright signal on T1 (Figure 5). Closer inspection revealed a subtle rim of dark signal on SSFP sequences, likely representing shell-like, peripheral calcifications. Caseous MAC were included among differential considerations. A CT scan of the chest was subsequently performed without contrast and demonstrated the typical appearance of caseous MAC (Figure 5).

Figure 5 A non-contrast CT image (kVp = 120, mAs = 214, DFOV = 322 mm) (A) performed after the cardiac MRI demonstrates again, a homogeneously hyperattenuating structure in the posterolateral mitral annulus (white arrow) with a shell of calcification (black arrow).

This corresponded with a T1 hyperintense structure in the region of the mitral annulus (B) (TR = 5.28, TE = 2.55, FA = 12). On a screen capture from a cine balanced steady state free precession sequence, the mass shows low T2 signal (C) (TR = 3.19, TE = 1.15, FA = 40), although the shell of calcification around the mass is slightly lower in T2 intensity than the central portion of the mass (white arrowhead). A short axis, delayed enhancement, inversion recovery image (D) (TR = 4.39, TE = 1.26, FA = 13) shows central low signal intensity as well, although there is some peripheral delayed enhancement around the mass (dashed arrow).

DISCUSSION

Calcification of the mitral annulus is usually considered an idiopathic, degenerative condition of the mitral annulus, occurring most commonly in older, female patients[7]. This condition is characterized by the development of coarse calcifications along the mitral annulus, and is seldom associated with other signs of mitral valve disease[8]. Rarely, MAC have also been described in patients with Marfan’s Syndrome[9], and in Barlow’s Disease, a disease of MAC and severe mitral valve prolapse[10].

Several studies have demonstrated that although commonly seen in asymptomatic patients, MAC may be a risk factor for more significant cardiovascular pathology. For example, MAC have been associated with conduction abnormalities[8], including atrial fibrillation[11], and with other cardiovascular diseases including coronary artery disease[12], and stroke risk[13]. In one study, the presence of MAC was associated with a two-fold increase in the risk of stroke, even in the absence of other risk factors[14]. This risk and other risks associated with MAC remain somewhat controversial, however[15].

MAC should be differentiated from calcifications within the mitral valve itself, which are usually related to significant mitral valve pathology and dysfunction, and are commonly seen in rheumatic heart disease. Valvular calcifications only extend to the annulus in end-stage or in severe rheumatic disease[16]. Unlike valvular calcifications, annular calcifications are more common and are more seldom associated with significant mitral valvular dysfunction, although when severe, MAC may in some cases be associated with mitral regurgitation[2,17,18]. To our knowledge, no studies have been conducted thus far to ascertain the clinical significance of caseous MAC specifically or differentiate the implications of caseous from non-caseous MAC.

Although MAC are encountered commonly, especially in the imaging of older patients, the liquefaction of MAC is an uncommon entity, and has been reported to occur in only approximately 0.6% of patients with MAC[2]. Caseous MAC are also rarely reported in the literature. The largest series to date of patients with caseous MAC includes 18 patients[19]. However, a large autopsy series reported an incidence of 2.7% of caseous MAC, suggesting that this entity may be under-recognized[1].

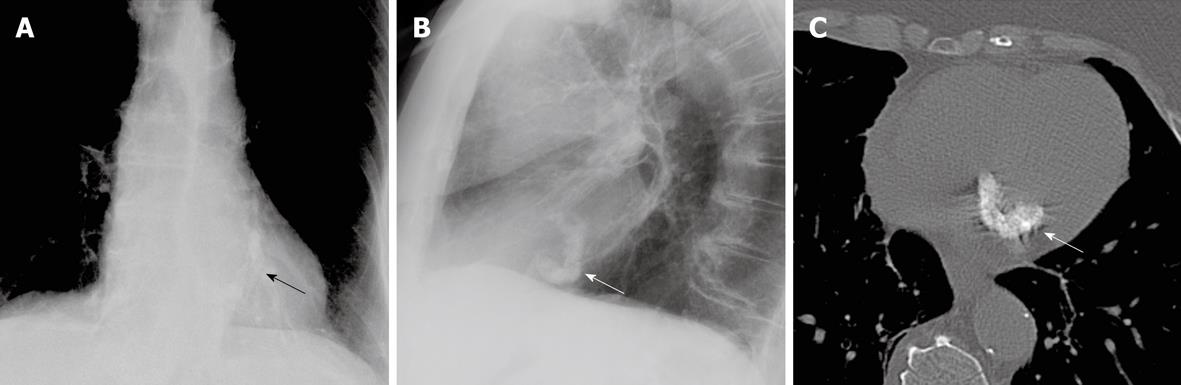

The distinction between MAC and caseous MAC can be made by the different imaging features of these entities. When these calcifications liquefy and become caseous, they have a more ovoid, mass-like appearance than non-caseous MAC. Whereas MAC seldom mimic a mass, caseous MAC are more focal, may be tumefactive, and should be included in differential diagnostic considerations of an intracardiac mass[20]. This entity is however, easily differentiated from other cardiac masses by the baseline, precontrast hyperattenuation on CT, without enhancement. As we report, the MRI characteristics are consistent with that of proteinaceous fluid. Identification of the shell of calcium, and classic localization in the mitral annulus are other classic features of this process. MAC typically have a coarse nature and form a C-shape around the mitral valve (Figure 6). These are most prominent along the posterolateral aspect of the mitral annulus. In contradistinction, caseous MAC have a more homogeneous attenuation, and are slightly less hyperattenuating than the non-liquefied state of calcium. This subtle difference in attenuation is usually masked on typical window and level settings employed for mediastinal settings. The caseous nature of MAC is however, better recognized on “bone windows”. This is elucidated in the first two patients presented. There is usually a shell of peripheral calcifications around the central homogeneous hyperattenuation, which was visible in all three of the cases presented in this study. Grossly, the caseous material found in this entity is described as toothpaste-like material[21].

Figure 6 In a different patient, not described herein, the more characteristic appearance of mitral annular calcifications is demonstrated (arrows).

These are seen on the P-A view (A), with window and level settings adjusted to better visualize the mitral annular calcifications. The typical C-shape of the mitral annular calcifications is also demonstrated on the lateral view (B) and on a non-contrast CT image through the level of the heart (C) (kVp = 120, mAs = 212, DFOV = 310 mm). Note the difference between the chunky, coarse, C-shaped calcifications seen in this patient and the ovoid, mass-like calcifications with liquefied calcium that we describe.

On MRI, calcium is generally low in signal on all sequences. However, the calcium salts and proteinaceous fluid in caseous MAC can generate high signal on T1 non-contrast sequences, which was seen on the CMR of the third patient we presented (Figure 5). Precontrast T1 weighted sequences are helpful in demonstrating the distinction between MAC which have low signal on T1, and caseous MAC which demonstrate high signal on T1. Liquefied calcium is low in T2 signal intensity. The T2 gated sequences in our patient showed decreased signal. Low signal was also seen on the cine SSFP sequences. In our patient, the calcified shell seen also demonstrated lower signal intensity than the rest of the mass of caseous MAC on cine SSFP. Delayed contrast enhancement has been reported along the periphery of caseous MAC[22]. This feature was noted in the third case presentation discussed above (Figure 5D).

The authors postulate that caseous MAC might be more common than usually recognized. This is supported by the presentations of the patients we have described. In the case of the first patient, the abnormality was present on two previous CT scans of the chest. In the second patient, the presence of caseous MAC initially was a diagnostic dilemma, but was recognized when the study was compared with a prior chest radiograph. These cases show that caseous MAC are not a commonly recognized entity.

Caseous MAC may mimic cardiac masses, but have a characteristic appearance which allows differentiation from more commonly encountered, non-caseous MAC. Although the presence of caseous MAC may pose a diagnostic dilemma, familiarity with the entity enables accurate diagnosis.