Published online Sep 28, 2024. doi: 10.4329/wjr.v16.i9.453

Revised: August 22, 2024

Accepted: August 26, 2024

Published online: September 28, 2024

Processing time: 163 Days and 6.4 Hours

Extralobar pulmonary sequestration (ELS) with torsion is extremely rare, con

Four children presented to our department with abdominal pain. All underwent chest computed tomography, which revealed an intrathoracic soft tissue mass with pleural effusion. All four children underwent thoracoscopic resection of the identified pulmonary sequestration, and the vascular pedicle was clipped and excised. None of the patients experienced any postoperative complications.

Clinicians should consider the possibility of ELS with torsion in children presen

Core Tip: Extralobar pulmonary sequestration (ELS) with torsion is relatively rare, and typically occurs in the left hemithorax. It generally presents in children; however, there is a high probability of misdiagnosis or missed diagnosis because of its atypical symptoms. As such, clinicians need to be more aware of the possibility of torsion of an ELS.

- Citation: Jiang MY, Wang YX, Lu ZW, Zheng YJ. Extralobar pulmonary sequestration in children with abdominal pain: Four case reports. World J Radiol 2024; 16(9): 453-459

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1949-8470/full/v16/i9/453.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4329/wjr.v16.i9.453

Pulmonary sequestration (PS) is a rare congenital lung malformation, which can be classified as either intralobar PS, or extralobar PS (ELS), based on the presence or absence of visceral pleura covering the lung parenchyma. Currently, the pathogenesis and etiology of PS remain unclear, while the clinical manifestations of ELS lack specificity. Asymptomatic children can be identified incidentally; however, some are not identified until they suddenly develop non-specific symptoms such as cough, sputum production, fever, hemoptysis, chest pain, chest tightness, shortness of breath, fatigue, and abdominal pain. Thus, missed and misdiagnosis of ELS with torsion are common because of its atypical symptoms.

Herein, we report four pediatric cases of abdominal pain caused by ELS torsion. All patients underwent thoracoscopic resection of the PS, following which postoperative pathological examination confirmed ELS with hemorrhagic infarction.

Case 1: A 3-year-old boy admitted to our hospital with abdominal pain for 7 days and fever for 5 days.

Case 2: A 7-year-old boy admitted to our hospital with abdominal pain and vomiting for 2 days.

Case 3: A 6-year-old girl admitted to our hospital with abdominal and chest pain for 10 days.

Case 4: A 10-year-old girl admitted to our hospital with abdominal pain for 4 days, and chest pain and fever for 3 days.

Case 1: The patient had a history of presentation to another hospital with abdominal pain and fever. Computed tomography (CT) of the abdomen revealed no intra-abdominal abnormalities; however, left-sided pleural effusion was observed. Subsequently, chest CT revealed a left-sided hyperdense opacity with pleural effusion, after which the patient was transferred to our hospital.

Case 2: The patient presented to our hospital with abdominal pain and vomiting.

Case 3: The patient had a history of presentation to another hospital with abdominal and chest pain. CT of the abdomen and chest revealed a mass with pleural effusion in the right chest, after which the patient transferred to our hospital.

Case 4: The patient presented to our hospital with abdominal and chest pain and fever.

All of the patients were previously healthy, and had no history of recurrent respiratory tract infection. All had been vaccinated with the tuberculosis (TB) vaccine, and denied any history of exposure to TB. Further, none had any history of eating contaminated or raw food.

Case 1: The patient's grandfather had nasopharyngeal cancer.

Cases 2-4: These patients had no remarkable personal or family history.

Case 1: The patient had decreased breathing sounds and voice tremors at the left lung base.

Cases 2-4: Physical examination was unremarkable.

Case 1: Laboratory examinations at admission revealed no abnormalities in blood cell count, blood biochemistry, or coagulation function. Tumor marker levels [carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) and alpha-fetoprotein (AFP)] were unremarkable, while cytological analysis of the pleural fluid yielded negative results for malignancy, and pleural fluid culture showed no growth of infectious organisms.

Case 2: Routine blood analysis revealed an elevated leukocyte count of 18.62 × 109/L, with 87.5% neutrophils and 5.0% lymphocytes; eosinophils were within the normal range. Tumor marker levels [CEA, AFP, neuron-specific-enolase (NSE), human chorionic gonadotropin (HCG), and urinary vanillylmandelic acid (VMA)] were unremarkable. No abnormalities were identified in other parameters related to blood biochemistry or coagulation.

Case 3: Tumor marker levels (CEA, AFP, NSE, HCG, and urinary VMA) were unremarkable. No abnormalities were identified in other laboratory tests results upon admission.

Case 4: Routine blood analysis revealed 82.4% neutrophils and 9.3% lymphocytes; the leukocyte count was 14.23 × 109/L; eosinophils were within the normal range. Tumor marker levels (CEA, AFP, NSE and HCG) were unremarkable. No abnormalities were identified in other laboratory tests upon admission.

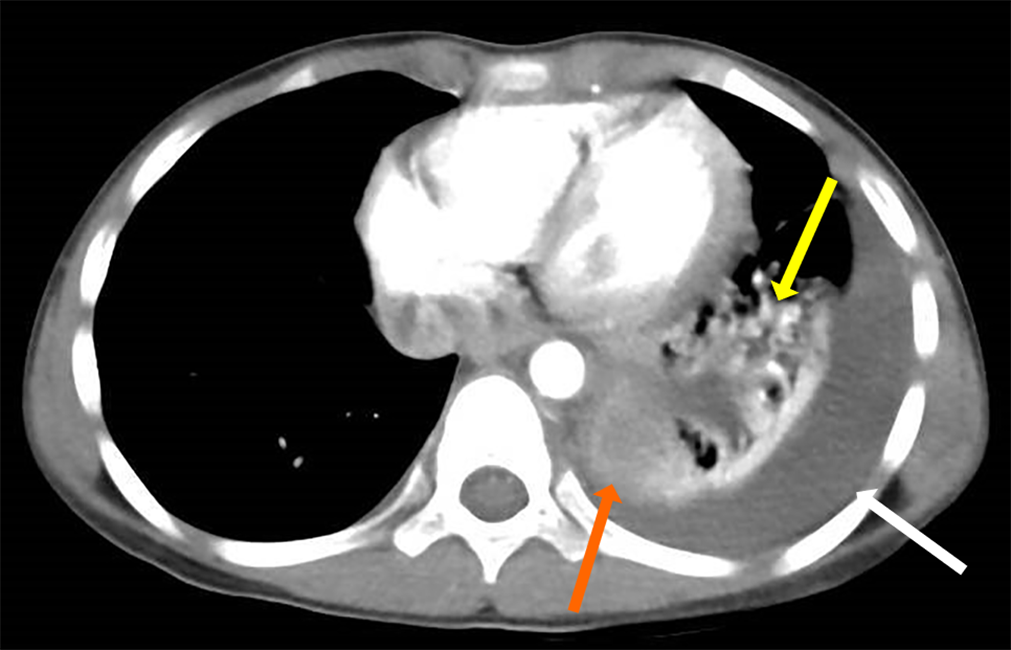

Chest CT revealed an intrathoracic soft tissue mass shadow with pleural effusion in all cases (Figure 1). Abdominal imaging showed no signs indicative of masses in the abdominal cavity.

Based on the postoperative pathological examination findings, the final diagnosis of ELS with torsion was confirmed in all four cases.

All patients underwent planned thoracoscopic resection of PS. Grayish-brown or purplish-dark masses with congestion and necrosis were observed during surgery, accompanied by bloody pleural effusion. The feeding arteries were identified and clipped.

None of the children experienced any intra- or postoperative complications; their symptoms were relieved after surgery, and they have reported no discomfort since discharge.

ELS is characterized by the presence of non-functional lung tissue encased in its own visceral pleura, with little or no communication with the tracheobronchial tree. The supply artery normally originates from the thoracic or abdominal aorta, while the venous drainage primarily reaches the inferior vena cava, azygos vein, or hemiazygos vein. ELS is commonly associated with other congenital abnormalities, of which congenital diaphragmatic hernia is the most common[1,2]. This is inconsistent with the 13 cases reported in the English literature (Table 1). None of the 17 reported patients, including our four, had other congenital malformations; indeed, all were previously healthy and did not undergo routine examination. As a result, ELS was not detected until symptom onset. Most congenital anomalies in children are diagnosed and surgically treated in the neonatal period. One study characterized the epidemiology of PS in a Chinese population, extracted from a nationwide database from 2010 to 2019. The authors found that 90.25% of children with PS were identified by prenatal ultrasound. Although the majority of the PS cases could be diagnosed prenatally, a few mild, asymptomatic cases of PS or complex syndrome may be missed, particularly in rural areas, which may be related to the diagnostic capacity of the examiners, location of the mass, socioeconomic status, and prenatal health care services[3].

| No. | Ref. | Published year | Age (year) | Sex | Main symptoms | Location | Pleural effusion | Imaging findings |

| 1 | Shih et al[4] | 1990 | 8 | F | Abdominal pain | Left abdomen | - | Contrast-enhanced abdominal CT revealed a thin-walled mass in the left retroperitoneum |

| 2 | Mammen et al[5] | 1994 | 8 | F | Abdominal and chest pain | Right | + | Chest radiographs revealed a right-side pleural effusion with collapse and consolidation of the right middle and lower lobes |

| 3 | Yokota et al[6] | 2019 | 15 | M | Abdominal pain and coughing | Right | - | Contrast-enhanced chest CT revealed a soft tissue density mass adjacent to the vertebral body at the posterior mediastinum |

| 4 | Lima et al[7] | 2010 | 11 | F | Abdominal pain | Left | + | Chest CT revealed a paraspinal mass in the inferior portion of the left chest |

| 5 | Walcutt et al[8] | 2021 | 13 | M | Abdominal and vomiting | Left | + | Contrast-enhanced chest CT revealed a hyperdense polygonal mass in the inferior medial left pleural space |

| 6 | Kirkendall et al[10] | 2013 | 13 | M | Abdominal and chest pain | Left | + | Chest CT revealed a paraspinal soft tissue mass in the inferior portion of the left chest |

| 7 | Chen et al[11] | 2011 | 13 | M | Abdominal pain and vomiting | Left | + | Chest CT revealed a well-defined posterior mediastinal soft tissue mass |

| 8 | Shah et al[13] | 2010 | 11 | F | Abdominal and chest pain | Left | + | Contrast-enhanced Chest CT revealed an ovoid soft-tissue density shadow |

| 9 | Uchida et al[14] | 2010 | 4 | M | Abdominal pain | Left | + | Contrast-enhanced Chest CT revealed an oval-shaped mass in the posteromedial left lower chest |

| 10 | Son et al[15] | 2020 | 13 | F | Abdominal and chest pain | Left | + | Chest CT revealed amass-like lesion in left hemithorax |

| 11 | Choe and Goo[17] | 2015 | 10 | M | Abdominal pain and fever | Left | + | Chest CT revealed well-defined hypodense soft tissue lesion in the left pleural space |

| 12 | Zucker et al[18] | 2013 | 6 | M | Abdominal pain and chest pain | Left | + | Contrast-enhanced chest CT revealed an oval-shaped mass in the left lower chest |

| 13 | Gawlitza et al[19] | 2014 | 11 | M | Abdominal and vomiting | Left | + | Contrast-enhanced chest CT revealed a mass with intermediate density in the left chest |

In the present study, we searched the PubMed, CNKI, Wanfang, and VIP databases from their inception to October 2021 for literature on ELS in children with abdominal pain as the primary manifestation. This search identified 13 cases of ELS with torsion previously reported in the literature (Table 1). The patients’ ages ranged from 4 to 15 years, and all were previously healthy. All patients presented with abdominal pain, while other symptoms include chest pain, vomiting, and fever. Except for the identification of a mass that was found in the left lower abdomen of one child[4] and massive consolidation accompanied by pleural effusion on chest radiography in another child[5], chest CTs of the other 11 children revealed a low-density soft tissue mass shadow in a triangular, oval, or round shape, and the ratio of the left and right parts of the lesion was 11:2. Only 2 of the 13 patients did not show pleural effusion[4,6]. Only 1 patient was diagnosed with two left ELS, of which one had torsion[7]. All children underwent surgical treatment. Based on postoperative pathological examination findings, a final diagnosis of ELS with torsion was confirmed in all cases. All patients were cured after surgery, with favorable outcomes and no deaths.

The ELS usually attaches to the mediastinal side of the pleural cavity only through the vascular pedicle and lower pulmonary ligament, while torsion of the ELS can easily occur during vigorous exercise, resulting in infarction, hemorrhage, and necrosis[6,8]. In addition, pleural effusion, which is usually bloody, can be attributed to the blockage of the draining venous and lymphatic vessels by torsion of the vascular pedicle. ELS is a rare congenital malformation characterized by acute onset and rapid progression. In adulthood, ELS most commonly presents as chest pain or discomfort[9]. In contrast, the most common clinical symptom in children is abdominal pain, which may be accompanied by vomiting and fever; thus, the initial evaluation generally focuses on abdominal diseases, such as acute abdomen[5,6,10] and neurogenic tumors[4,11]. Among the previously reported cases, one patient was preoperatively diagnosed with neuroblastoma with negative chest radiography findings and elevated urinary VMA, which is suggestive of tumors of neural crest origin[4].

The four children with ELS with torsion hospitalized in our institution all had abdominal pain as the first or primary symptom, while accompanying symptoms included fever, chest pain, and vomiting. Further, in all patients, chest CT revealed an intrathoracic soft tissue mass shadow between the lower lobe of the lung and the diaphragm, combined with pleural effusion. The preoperative differential diagnoses of ELS include tumor, diaphragmatic herniation, and unusual infections such as TB infection, parasitic infection, and unclear disease. We progressively excluded these differential diagnoses based on the following findings: (1) All patients had received the TB vaccine, and denied a history of exposure to TB; (2) None of the patients had any history of eating contaminated or raw food; and (3) Tumor marker levels (CEA, AFP, NSE, HCG, and urinary VMA) were unremarkable, while routine blood analysis revealed normal levels of eosinophils.

As mentioned, abdominal pain is one of the common symptoms of ELS in children. Abdominal pain in children has many potential causes, which can be broadly categorized into intra-abdominal disease, extra-abdominal, and systemic disease; further, thoracic diseases such as pneumonia, pleurisy, pulmonary infarction, and pericarditis can cause abdominal referred pain. The pathogenesis of abdominal pain is divided into visceral abdominal pain[12], somatic abdominal pain, and referred pain. The ELS is usually located between the lower lobe of the lung and the diaphragm. In all 17 reported cases, including our own, imaging evaluation revealed a soft tissue lesion located between the diaphragm and lower lobe. In our 4 cases, the mass was densely adherent to the chest wall and diaphragm at operation. However, at present, literature reports on ELS in children with abdominal pain as the main manifestation are rare, and most of those that have been published are retrospective case reports. The mechanism of abdominal pain is not clear and requires further exploration. The causes of abdominal pain caused by ELS with torsion could be: (1) Pneumonia or pleurisy caused by the torsion of ELS causes referred pain; (2) ELS is generally located between the diaphragm and the lower lobe, and abdominal pain could be attributed to irritation to the diaphragm caused by torsion of the ELS; (3) ELS can be found infra- diaphragmatically, representing an extremely rare type of PS. In such cases, peritonitis or peritoneal effusion caused by the torsion of this kind of ELS causes abdominal pain.

Currently, chest imaging examination is the key method for establishing a correct diagnosis of ELS when a feeding artery arising from the systemic circulation into the isolated lung tissue is identified. Chest imaging tests should be performed as early as possible to exclude ELS with torsion when school-age children present with abdominal pain, while chest imaging should range from the lower thorax to the level of the pulmonary veins[13], with the entire chest ideally being examined. Routine chest radiography or chest CT without contrast-enhanced imaging may reveal a mass shadow in the lung; however, it has a high rate of misdiagnosis. Particularly in the early stage of the disease, it may be missed or misdiagnosed as atelectasis[10,14]. Son et al[15] indicated that an image might be misdiagnosed as a tumorous or infectious condition, if an inflammatory reaction occurs. Contrast-enhanced CT with 3D reconstruction is more effective at diagnosing ELS, as it provides more information about the mass, such as the degree of enhancement of the mass and the vascular shadow of the lesion, which makes it easier to distinguish pulmonary cystic lesions, consolidation, atelectasis, and mass shadow. However, torsion of the vessels can hinder the visibility of the blood supply, while contrast-enhanced CT may not identify an abnormal blood supply. Ou et al[16] Previously reported the clinical characteristics of 48 cases (including 30 confirmed and 18 suspected cases) of PS in children. Among them, only 16 were confirmed by imaging preoperatively, including four cases by chest CT-enhanced scanning, nine cases by enhanced CT combined with three-dimensional reconstruction, and three cases by digital subtraction angiography; the misdiagnosis rate was 36.7%, and the missed diagnosis rate was 10%. Torsion of the ELS prevents the blood supply from being filled with contrast medium, resulting in unrecognizable blood supply vessels and atypical imaging findings. This leads to difficulty in diagnosing ELS with torsion. As such, it is also difficult to identify the abnormal supply artery of the ELS with torsion using contrast-enhanced CT combined with three-dimensional reconstruction, which requires radiologists to pay close attention to it to avoid missing diagnoses. Of the 13 reported cases, a feeding artery was identified on MRI in only one case[17]. Shah et al[13], Zucker et al[18] and Gawlitza et al[19] all indicated that torsion of the PS could be considered, even if the classic findings of a vascular pedicle were not identified on imaging examinations.

Most cases of ELS are diagnosed antenatally, and are treated aggressively with surgery, even if asymptomatic. However, some pediatric ELS are not identified during prenatal examination; such patients are usually in good health, and may only be admitted to the hospital because of pulmonary infarction and hemorrhage caused by torsion of the blood vessel pedicle. These patients also require immediate surgery. Currently, thoracoscopic surgery is an important treatment for ELS associated with torsion, less intraoperative bleeding, and better recovery and prognosis[20].

ELS with torsion usually presents in children and adolescents, and is associated with a high risk of missed or misdiagnosis because of its atypical symptoms. Clinicians should consider the possibility of ELS with torsion in previously healthy school-aged children with chief complaints of abdominal pain, sometimes accompanied by chest pain, vomiting, and fever. Chest imaging should also be performed as early as possible, particularly in cases with remarkable findings on physical examination of the lungs suggestive of ELS with torsion. A high index of suspicion for ELS with torsion should be maintained when contrast-enhanced chest CT reveals a soft tissue mass shadow with no or mild enhancement, accompanied by bloody pleural effusion, unclear blood supply arteries, and other characteristic changes. As such, thoracoscopic ELS resection should be performed immediately.

We would like to thank the patient’s family members for providing detailed treatment information.

| 1. | Chakraborty RK, Modi P, Sharma S. Pulmonary Sequestration. 2023 Jul 24. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2024 Jan-. [PubMed] |

| 2. | Yildirim G, Güngördük K, Aslan H, Ceylan Y. Prenatal diagnosis of an extralobar pulmonary sequestration. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2008;278:181-186. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Gao Y, Xu W, Li W, Chen Z, Li Q, Liu Z, Liu H, Dai L. Epidemiology and prevalence of pulmonary sequestration in Chinese population, 2010-2019. BMC Pulm Med. 2023;23:8. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Shih SL, Lin JC, Chen BF, Chen CC, Chang KL, Liang DC. Extralobar pulmonary sequestration of the left retroperitoneum. Australas Radiol. 1990;34:356-357. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Mammen A, Myers NA, Beasley SW. Torsion and infarction of an extralobar pulmonary sequestration. Pediatr Surg Int. 1994;9:399-400. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 6. | Yokota R, Sakamoto K, Urakawa H, Takeshita M, Yoshimitsu K. Torsion of right lung sequestration mimicking a posterior mediastinal mass presenting as acute abdomen: Usefulness of MR imaging. Radiol Case Rep. 2019;14:551-554. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Lima M, Randi B, Gargano T, Tani G, Pession A, Gregori G. Extralobar pulmonary sequestration presenting with torsion and associated hydrothorax. Eur J Pediatr Surg. 2010;20:208-210. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Walcutt J, Abdessalam S, Timmons Z, Winningham P, Beavers A. A rare case of torsion and infarction of an extralobar pulmonary sequestration with MR, CT, and surgical correlation. Radiol Case Rep. 2021;16:3931-3936. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Yang L, Yang G. Extralobar pulmonary sequestration with a complication of torsion: A case report and literature review. Medicine (Baltimore). 2020;99:e21104. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Kirkendall ES, Guiot AB. Torsed pulmonary sequestration presenting with gastrointestinal manifestations. Clin Pediatr (Phila). 2013;52:981-984. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Chen W, Wagner L, Boyd T, Nagarajan R, Dasgupta R. Extralobar pulmonary sequestration presenting with torsion: a case report and review of literature. J Pediatr Surg. 2011;46:2025-2028. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Ehrhardt JD, Weber C, Carey FJ, Lopez-Ojeda W. Anatomy, Thorax, Greater Splanchnic Nerves. 2024 Jan 31. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2024 Jan-. [PubMed] |

| 13. | Shah R, Carver TW, Rivard DC. Torsed pulmonary sequestration presenting as a painful chest mass. Pediatr Radiol. 2010;40:1434-1435. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Uchida DA, Moore KR, Wood KE, Pysher TJ, Downey EC. Infarction of an extralobar pulmonary sequestration in a young child: diagnosis and excision by video-assisted thoracoscopy. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A. 2010;20:399-401. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Son SA, Do YW, Kim YE, Lee SM, Lee DH. Infarction of torsed extralobar pulmonary sequestration in adolescence. Gen Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2020;68:77-80. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Ou J, Lei X, Fu Z, Huang Y, Liu E, Luo Z, Peng D. Pulmonary sequestration in children: a clinical analysis of 48 cases. Int J Clin Exp Med. 2014;7:1355-1365. [PubMed] |

| 17. | Choe J, Goo HW. Extralobar pulmonary sequestration with hemorrhagic infarction in a child: preoperative imaging diagnosis and pathological correlation. Korean J Radiol. 2015;16:662-667. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Zucker EJ, Tracy DA, Chwals WJ, Solky AC, Lee EY. Paediatric torsed extralobar sequestration containing calcification: Imaging findings with pathological correlation. Clin Radiol. 2013;68:94-97. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Gawlitza M, Hirsch W, Weißer M, Ritter L, Metzger RP. Torsion of extralobar lung sequestration - lack of contrast medium enhancement could facilitate MRI-based diagnosis. Klin Padiatr. 2014;226:38-39. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Iga N, Nishi H, Miyoshi S. Video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery for bilateral intralobar pulmonary sequestration. Int J Surg Case Rep. 2018;53:333-336. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |