Published online Aug 28, 2024. doi: 10.4329/wjr.v16.i8.356

Revised: June 20, 2024

Accepted: July 18, 2024

Published online: August 28, 2024

Processing time: 141 Days and 3.1 Hours

Orificial tuberculosis is a rare type of tuberculosis, which is easy to be misdiagnosed, and can cause great damage to the perianal skin and mucosa. Early diagnosis can avoid further erosion of the perianal muscle tissue by tuberculosis bacteria.

Here, we report a case of disseminated tuberculosis in a 62-year-old male patient with a perianal tuberculous ulcer and active pulmonary tuberculosis, intestinal tuberculosis and orificial tuberculosis. This is an extremely rare case of cutaneous tuberculosis of the anus, which was misdiagnosed for nearly a year. The patient received conventional treatment in other medical institutions, but specific treatment was delayed. Ultimately, proper diagnosis and treatment with standard anti-tuberculosis drugs for one year led to complete cure.

For skin ulcers that do not heal with repeated conventional treatments, consider ulcers caused by rare bacteria, such as Mycobacterium tuberculosis.

Core Tip: The occurrence of perianal ulcer is generally considered bacterial or fungal infection. If long-term treatment is ineffective, rare infection types such as tuberculosis infection should be considered. Early diagnosis can avoid the erosion of perianal skin, mucous membranes and muscles. We report a case of disseminated tuberculosis in a 62-year-old male patient with a perianal tuberculous ulcer and active pulmonary, intestinal and orificial tuberculosis. A computed tomography scan revealed active tuberculosis, whereas a colonoscopy showed lesions in the ileum, suggestive of intestinal tuberculosis. The pathology report was consistent with granulomatous inflammation, and the histological analysis of the ulcer and perianal granulation tissue revealed granulomatous lesions of unknown nature. The T-spot test was positive. The patient was treated and cured with standard anti-tuberculosis drugs, whose regimen we describe in this case study.

- Citation: Yuan B, Ma CQ. Perianal tuberculous ulcer with active pulmonary, intestinal and orificial tuberculosis: A case report. World J Radiol 2024; 16(8): 356-361

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1949-8470/full/v16/i8/356.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4329/wjr.v16.i8.356

Tuberculosis, a chronic infectious disease, is mainly transmitted through the respiratory tract. It is one of the oldest diseases in human history, and it can be said that tuberculosis has been around since the existence of humans. Tuberculosis is also the world’s leading cause of death. In 2022, it was estimated that there were 10.6 million cases worldwide (88% of adults, 55% of men, 33% of women and 12% of children), the tuberculosis incidence rate is estimated to have increased by 3.9% between 2020 and 2022, from 128 in 2020 to 133 in 2022[1]. This may be due to increased tuberculosis transmission associated with the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic. Globally in 2022, tuberculosis caused an estimated 1.30 million deaths[1]. Despite being preventable and usually curable, tuberculosis remained the world’s second leading cause of death from a single infectious agent in 2022, after coronavirus disease 2019, and caused almost twice as many deaths as human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)/acquired immunodeficiency syndrome[1].

The lungs are the main organ to receive a tuberculosis bacillus infection, and this includes the trachea, bronchus and pleura, but it can also occur in other organs such as the lymph nodes (excluding the intrathoracic lymph nodes), bone, arthrosis, urogenital system, digestive system, central nervous system and skin. This type of tuberculosis is known as extrapulmonary tuberculosis. Here, we report a case of disseminated tuberculosis in a 62-year-old male patient with a perianal tuberculous ulcer and active pulmonary, intestinal and orificial tuberculosis.

A 62-year-old man with unbearable pain due to a perianal ulcer, accompanied by seepage, was admitted to our hospital in October 2016.

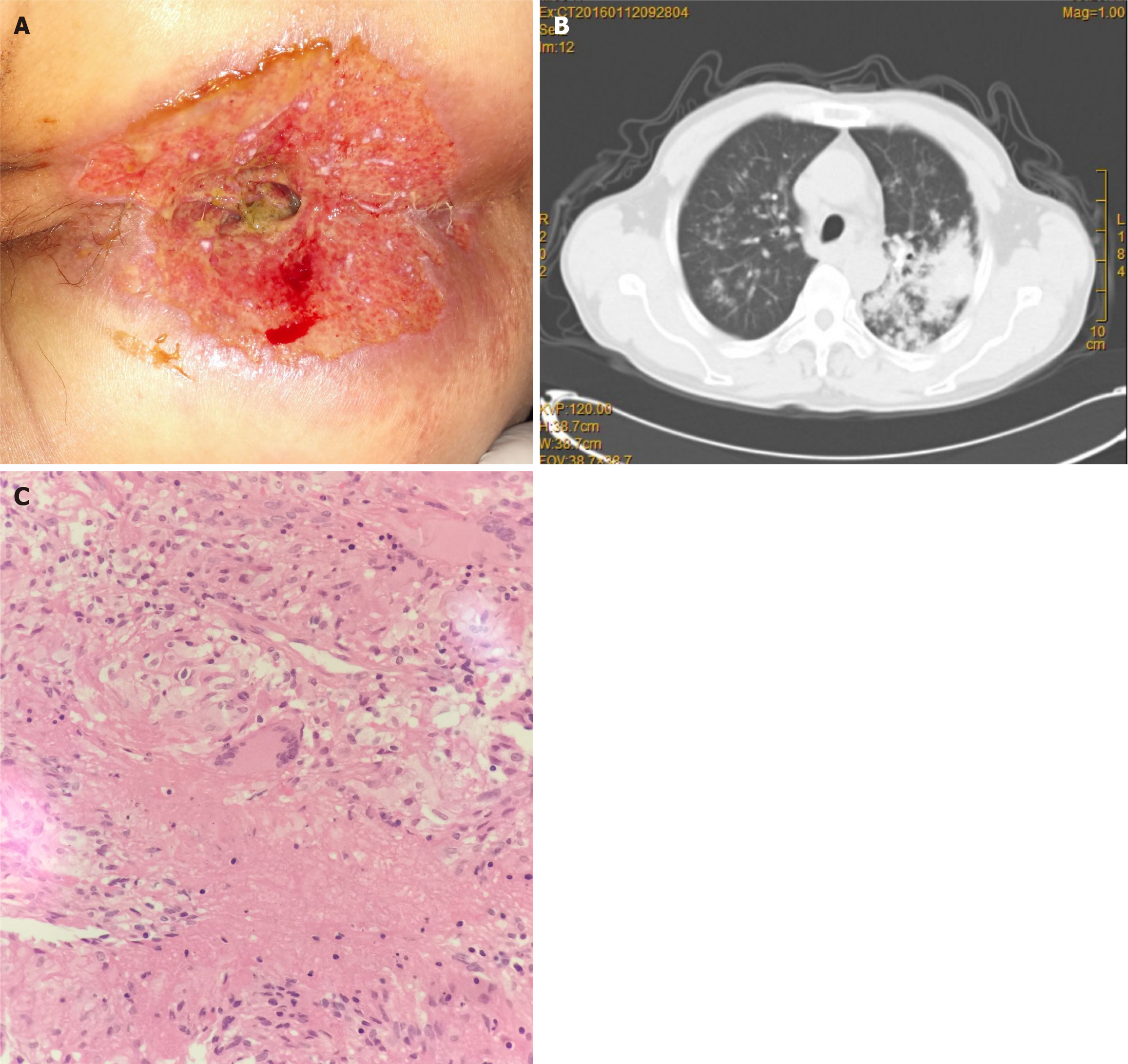

A perianal ulcer with an approximate diameter of 10 cm (Figure 1A), accompanied by pain, appeared 10 months ago. The patient previously visited another well-known hospital, where he was diagnosed with perianal eczema, which was cleansed with a bactericidal agent and dressed with a bandage. Although the symptoms improved, the ulcer failed to completely heal. Subsequently, the pain returned, and the ulcer gradually increased in size. In the 10 days prior to being admitted to our hospital, there was bleeding accompanied by hemorrhagic exudation.

The patient’s history of past illness included tuberculosis (cured 40 years ago with standard treatment) and chronic viral hepatitis B.

There was no patient and familial history of other diseases such as HIV, hypertension and diabetes. There was no patient history of smoking and exposure to toxic agents, as well as no history of surgery, trauma, blood transfusion, and food and drug allergies.

The patient presented with a temperature of 36.5 °C, a pulse of 87 beats per minute, and a blood pressure of 122/78 mmHg. There was occasional coughing with sputum production; however, there was no hemoptysis, night sweats, abdominal pain, diarrhea and emaciation. The patient’s stool was thin and deformed in shape, accompanied by a small amount of bright blood. The physical examination indicated an erosion of the perianal skin, with an approximate surface area of 12 cm × 10 cm, and exudation, with a small amount of pale skin remaining at the proximal anus. The residual tissue was characterized by an erosion, with obvious purulent secretions on the surface. A digital rectal examination indicated an ulcerative cavity approximately 2 cm deep in the middle of the posterior anus. The mucous membrane around the ulcer was granulomatous hyperplasia, like crater-like, and several uneven induration hyperplasia tissues were touched inside the anus. The pain was intense, and the muscle surrounding the anus was stiff and inflamed. Many pyogenic hemorrhagic secretions were noted upon withdrawal of a fingertip.

The proportion of monocytes was 13.4%, and the number of monocytes was 1.07 × 106. The level of hypersensitive C-reactive protein was 31.20 mg/L, and the erythrocyte sedimentation rate was 57 mm/H. T cells tested positive for tuberculosis infection. The liver and kidney function, tumor indices and other blood test results were normal. The sputum was twice as positive for acid-fast bacilli. Sputum culture was performed without pathogenic bacterial growth. Perianal secretions were cultured three times, and the resulting strains were Escherichia coli, Enterococcus faecium, and Enterococcus faecium. No tuberculosis bacilli were found.

A computed tomography (CT) scan showed diffuse lesions with partial calcification in both lungs, suggestive of active tuberculosis (Figure 1B). The wall of the distal ileum was thickened suggesting a malignant tumour. A gastroscopy revealed bile reflux gastritis, whereas a colonoscopy revealed ileocecal proliferative and ulcerative lesions, suggestive of intestinal tuberculosis. Routine sputum culture revealed no growth of pathogenic bacteria while acid fast staining was positive for acid-fast bacilli.

The colonoscopy pathology report was consistent with granulomatous inflammation, and histological analysis of the ulcer and perianal granulation tissue revealed granulomatous lesions. Granulomatous lesions appeared as tuberous nodules with caseous necrosis in the center of the nodules, and the surrounding necrotic tissue consisted of epithelioid cells and scattered Langerhans giant cells. The lateral surface of the nodules consisted of lymphocytes and a small number of fibroblasts with reactive hyperplasia (Figure 1C). Multiple neutrophilic granulocytes and a few low-grade dysplastic squamous epithelial cells were found during the cytological examination of the exfoliating wound, and no malignant cells were found.

Combined with the patient’s medical history, the final diagnosis was perianal tuberculous ulcer with active pulmonary, intestinal and orificial tuberculosis.

Subsequently, he was referred to a designated tuberculosis medical institution for further diagnosis and treatment in a specialist hospital of infectious diseases. According to the recommendations of Chinese guidelines for anti-tuberculosis treatment, he was given a 2HRZSE/4-6hRE regimen: (1) Intensive period: Isoniazid, rifampicin, pyrazinamide, streptomycin and ethambutol, once a day for 2 months; and (2) Consolidation period: Isoniazid, rifampicin and ethambutol once daily for 4 months.

After treatment, the ulcer significantly improved, and no new skin lesions were found. The consolidation treatment regimen continued for another 6 months, and the duration of the entire course of treatment was 1 year. The lesions of perianal skin tuberculosis, pulmonary tuberculosis and intestinal tuberculosis all healed. No abnormalities were found during follow-up until December 2023.

This is an initial case of perianal skin ulcer, which was admitted for diagnosis and treatment due to aggravation of perianal pain. My specialty is also a well-known local anorectal specialty, with an annual outpatient treatment volume of about 16000 people. Our team has never seen such disease in nearly 10 years. There was also some misdiagnosis in the clinic, due to the suspicion of eczema-like cancer, a series of tumor screening was performed, and the final diagnosis was perianal tuberculosis.

In China, tuberculosis has been effectively controlled by its prevalent characteristics of high morbidity and high mortality. In 2022, the number of tuberculosis infections in China accounts for about 7.1% of the world, with a total of 748000 tuberculosis cases and an incidence rate of 52/100000[1]. In China, the incidence of tuberculosis in males over 15 years old is 67%, that in females is 31%, and that in children aged 0-14 years old is 2%[1]. According to a 2010 epidemiological survey, the tuberculosis prevalence rate was higher in men than in women, and it gradually increased with advancing age[2]. Furthermore, tuberculosis is more likely to attack individuals with poor immune systems, such as those with HIV[3] and diabetes, as well as those receiving long-term treatments with glucocorticoids and the elderly.

Here, we report a case of an elderly patient with a history of perianal tuberculous ulcer with pulmonary, intestinal and orificial tuberculosis. Due to endogenous factors, pulmonary tuberculosis in patients leads to the occurrence of intestinal tuberculosis and orificial tuberculosis via autoinfection. The recessed ulcer at the mucosal junction of the perianal skin gradually spreads to the surrounding skin, leading to tuberculous ulcers of the perianal skin. Before hospitalization, the patient had repeatedly visited dermatological and anorectal departments, where he was diagnosed with perianal eczema or perianal fungal infection. Upon admission to our hospital, we initially considered a perianal skin infection (and did not exclude the possibility of perianal eczema-like cancer). We performed a comprehensive pulmonary CT scan, an abdominal CT scan, a colonoscopy, a wound biopsy, a secretion culture, a sputum culture and other related examinations. After the suspicion of tuberculosis and intestinal tuberculosis, the T-spot tuberculosis test was performed[4]. A diagnosis of perianal tuberculous ulcer with active pulmonary, intestinal and orificial tuberculosis was confirmed after collectively examining the medical history, clinical manifestations and examination results.

Cutaneous tuberculosis is defined as skin damage caused by the direct entry of the tuberculosis foci of the tuberculosis bacillus, followed by invasion of the lymphatic system. Cutaneous tuberculosis is a rare disease, accounting for 1%-1.5% of all types of extrapulmonary tuberculosis[5]. Orificial tuberculosis, also known as skin mucosa ulcerative tuberculosis, is a rare type of tuberculosis that occurs on the skin and mucosa, most commonly in the mouth and anus. Orificial tuberculosis is an endogenous infection caused by self-inoculation, i.e., the tuberculosis bacillus is inoculated into the adjacent skin and mucosa through natural orifices. A major risk factor for the development of orificial tuberculosis is low immunity, and it often occurs in patients with active tuberculosis, genital tuberculosis, urinary tuberculosis or intestinal tuberculosis. Furthermore, associated nodules or ulcers are difficult to treat and heal.

Anal tuberculosis is reported to be either absent or exceedingly rare[6]. They may present as pilonidal sinus or anal ulceration, anal fissure, anal strictures, and rectal submucosal tumor which are few other atypical presentations of the disease[7]. Presently, the main manifestations of anal tuberculosis are perianal abscesses and anal fistulas, which occur in 80%-91% of cases, followed by complex lesions, which occur in 62%-100% of cases[7,8]. The clinical features are non-healing wounds or postoperative recurrence. However, there are only very few reported case of a perianal tuberculous ulcer, and the misdiagnosis rate is very high. In addition, tuberculous ulcer lesions of the anus are often accompanied by other bacterial infections. Although non-tuberculous bacteria are often detected in the secretions of such lesions, an effort should be made to screen such lesions for Mycobacterium tuberculosis using various modalities like acid- fast staining, culture and molecular methods.

To conclude, perianal tuberculosis is seldom diagnosed based on the clinical picture. In the presence of large, painful perianal ulcers not healing on conventional treatment it is necessary to do routine screening for tuberculosis to consider the possibility of tuberculous ulcers, for early diagnosis and timely institution of anti-tuberculosis treatment.

We appreciate all participants associated with this study.

| 1. | World Health Organization. Global tuberculosis report 2023. [cited 25 January 2024]. Available from: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240083851. |

| 2. | Gao L, Bai L, Liu J, Lu W, Wang X, Li X, Du J, Chen X, Zhang H, Xin H, Sui H, Li H, Su H, He J, Pan S, Peng H, Xu Z, Catanzaro A, Evans TG, Zhang Z, Ma Y, Li M, Feng B, Li Z, Guan L, Shen F, Wang Z, Zhu T, Yang S, Si H, Wang Y, Tan Y, Chen T, Chen C, Xia Y, Cheng S, Xu W, Jin Q; LATENTTB-NSTM study team. Annual risk of tuberculosis infection in rural China: a population-based prospective study. Eur Respir J. 2016;48:168-178. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Havlir DV, Barnes PF. Tuberculosis in patients with human immunodeficiency virus infection. N Engl J Med. 1999;340:367-373. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 305] [Cited by in RCA: 265] [Article Influence: 10.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Leung CC, Yam WC, Ho PL, Yew WW, Chan CK, Law WS, Lee SN, Chang KC, Tai LB, Tam CM. T-Spot.TB outperforms tuberculin skin test in predicting development of active tuberculosis among household contacts. Respirology. 2015;20:496-503. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | van Zyl L, du Plessis J, Viljoen J. Cutaneous tuberculosis overview and current treatment regimens. Tuberculosis (Edinb). 2015;95:629-638. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 112] [Cited by in RCA: 127] [Article Influence: 11.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Candela F, Serrano P, Arriero JM, Teruel A, Reyes D, Calpena R. Perianal disease of tuberculous origin: report of a case and review of the literature. Dis Colon Rectum. 1999;42:110-112. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 37] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Gupta PJ. Ano-perianal tuberculosis--solving a clinical dilemma. Afr Health Sci. 2005;5:345-347. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Nadal SR, Manzione CR. Diagnósticoe tratamento da tuberculoseanoperianal. Rev Assoc Med Bras. 2002;48. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |