Published online Nov 28, 2024. doi: 10.4329/wjr.v16.i11.683

Revised: September 26, 2024

Accepted: October 25, 2024

Published online: November 28, 2024

Processing time: 149 Days and 17.6 Hours

Small bowel bezoar obstruction (SBBO) is a rare clinical condition characterized by hard fecal masses in the small intestine, causing intestinal obstruction. It occurs more frequently in the elderly and bedridden patients, but can also affect those with specific gastrointestinal dysfunctions. Diagnosing SBBO is challenging due to its clinical presentation, which mimics other intestinal obstructions. While surgical intervention is the typical treatment for SBBO, advancements in endo

We report a case of small bowel obstruction induced by a phytobezoar. A 49-year-old male with a history of type 2 diabetes and long-term persimmon consumption presented to the hospital with symptoms of vomiting, abdominal distension, and constipation. Computed tomography revealed a small bowel obstruction with foreign bodies. Double balloon enteroscopy identified a phytobezoar blocking the intestinal lumen. The bezoar was successfully fragmented using a snare, and the fragments were treated with 100 mL of paraffin oil to facilitate their passage. This case report aims to enhance the understanding of this rare condition by detailing the clinical presentation, diagnostic process, and treatment outcomes of a patient with SBBO. Special attention is given to the application and effectiveness of non-surgical treatment methods, along with strategies to optimize patient manage

Double balloon enteroscopy combined with sequential laxative therapy is an effective approach for the treatment of a breakable phytobezoar.

Core Tip: This case shows the successful treatment of a small intestinal phytobezoar using double balloon enteroscopy combined with sequential catharsis. Paraffin oil effectively prevents secondary obstruction caused by the accumulation of fragments in the intestine. Sequential catharsis may aid in the expulsion of the bezoar and help prevent recurrence. It is essential for the physician to ensure that the bezoar is completely expelled, as this represents the optimal end point of the treatment.

- Citation: Lu BY, Zeng ZY, Zhang DJ. Successful treatment of small bowel phytobezoar using double balloon enterolithotripsy combined with sequential catharsis: A case report. World J Radiol 2024; 16(11): 683-688

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1949-8470/full/v16/i11/683.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4329/wjr.v16.i11.683

Small bowel phytobezoar is a rare clinical condition characterized by the formation of indigestible food residue masses within the small intestine, leading to intestinal obstruction. This condition is more commonly observed in elderly individuals and patients who are bedridden for extended periods, but can also affect other patients with specific gastrointestinal dysfunctions. Due to its clinical presentation, which often mimic other types of intestinal obstructions, diagnosing small bowel phytobezoar can be challenging.

Although a small bowel phytobezoar is relatively rare in clinical practice, it can result in severe complications such as intestinal perforation, necrosis, and septic shock, necessitating prompt recognition and appropriate treatment by physicians. However, the incidence, risk factors, and optimal treatment strategies for small bowel phytobezoar remain poorly understood due to the lack of extensive epidemiological studies.

Current literature primarily suggests surgical intervention for the treatment of bezoar-induce small bowel obstruction, but with advancements in endoscopic techniques, non-surgical approaches such as endoscopic lithotripsy are increa

The purpose of this case report is to enhance the understanding of this rare condition by detailing the clinical presentation, diagnostic process, and treatment outcomes of a patient with a small bowel phytobezoar. We focus on the application and effectiveness of non-surgical treatment methods and discuss how to optimize patient management strategies. The patient has agreed to the publication of the case report and has signed the informed consent form.

The patient was vomiting, with abdominal distension and constipation for 1 week.

A 49-year-old man presented to our hospital complaining of vomiting, abdominal distension, and constipation. The patient suffered from type 2 diabetes and reported several years of persimmon ingestion, but no surgical history was mentioned. An abdominal computed tomography (CT) scan performed at another hospital revealed a small bowel obstruction with foreign bodies in the small intestine behind the navel, which were considered to be food residues.

The patient suffered from type 2 diabetes, for which he takes metformin. No surgical history, serious injuries, or infections were mentioned.

Personal history: The patient was a 49-year-old male. He had completed university and worked as a civil servant for over 20 years. He reported several years of persimmon ingestion. He neither smokes nor drinks alcohol. There is no history of illicit drug use. The patient denies any known allergies.

Family history: There is no known family history of cancer or genetic disorders. His siblings are all in good health with no significant medical conditions.

The abdominal examination revealed abdominal distension and mild tenderness, but no rebound tenderness or rigidity.

Initial laboratory tests showed a white blood cell count of 14.61 × 109/L and C-reactive protein levels of 107.55 mg/L. There were no obvious abnormalities detected in biochemistry profile, urinalysis, stool analysis, or serology.

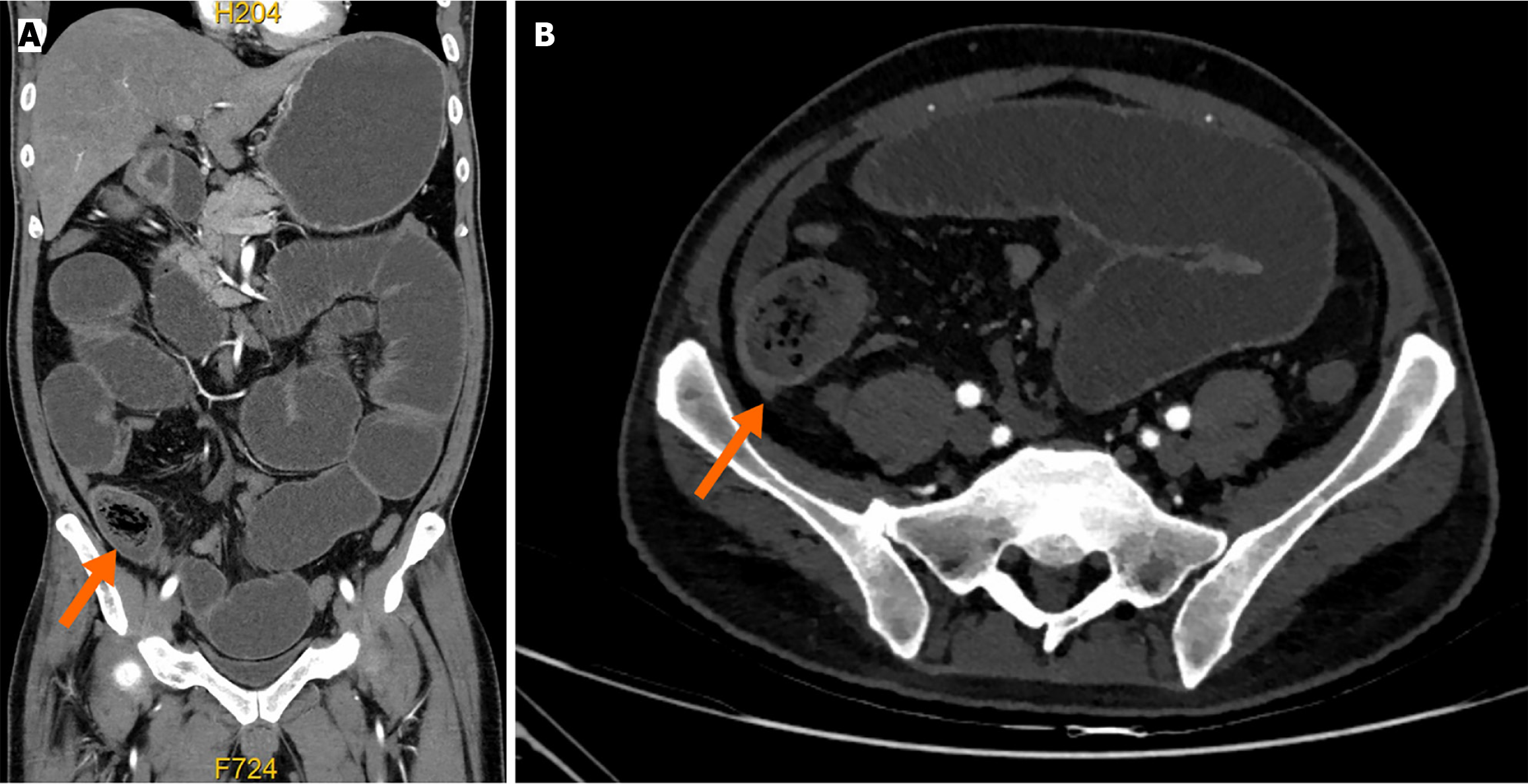

The abdominal contrast-enhanced CT showed dilatation of the stomach, duodenum, jejunum, and part of the ileum, with significant fluid, as well as a mass of 5 cm in diameter (Figure 1). The patient was admitted to the hospital and 2 days later, a long intestinal tube was inserted endoscopically, followed by gastrointestinal decompression and nutritional support treatment. One week later, a full gastrointestinal contrast was conducted, which showed signs of partial small bowel obstruction and slow gastric emptying (Figure 2).

The final diagnosis was bezoar-induced small bowel obstruction and type 2 diabetes mellitus.

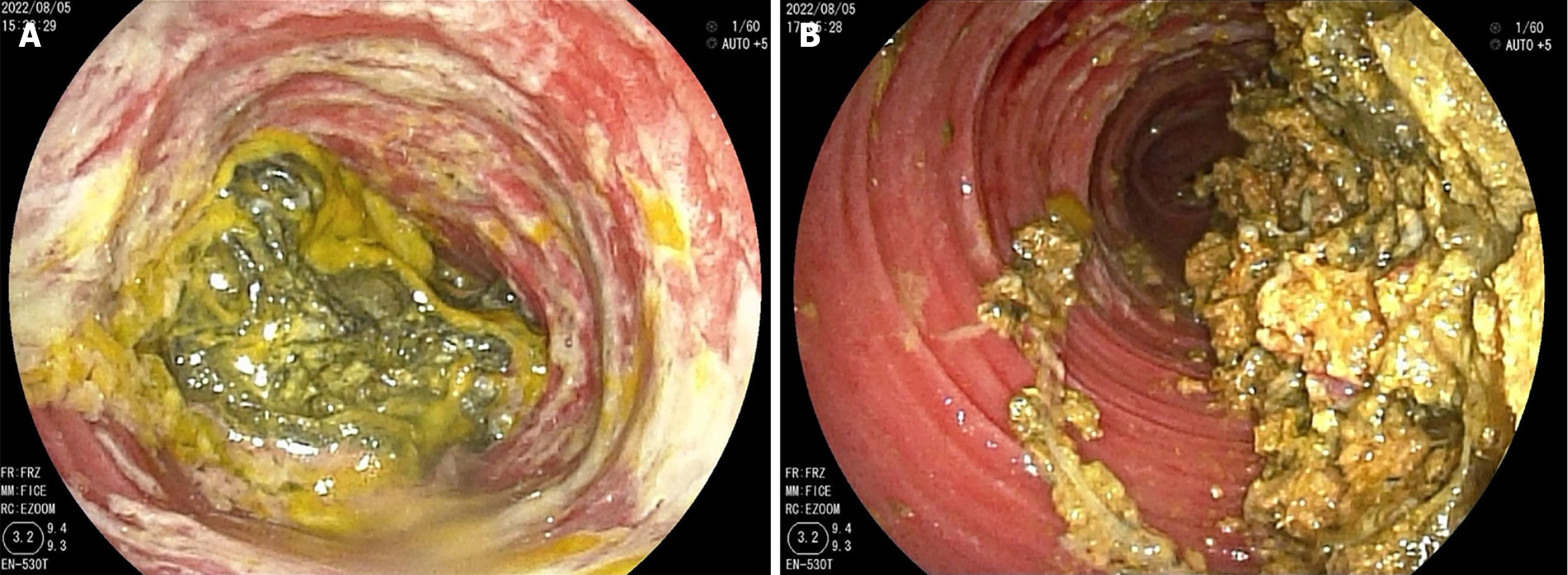

Although the patient’s clinical symptoms and intestinal dilatation improved, the diagnosis remained uncertain. Double balloon enteroscopy revealed multiple erosions of the intestinal mucosal in the jejunum. At 320 cm from the pylorus, a yellow-green, soft, medium-sized mass was observed blocking the intestinal lumen (Figure 3A). Lithotripsy was performed using a snare. The bezoar was smashed into small pieces. Given the fibrous nature of the pieces, our conclusion was that the foreign body was a phytobezoar. Then, paraffin oil (approximately 100 mL) was injected into the area where the foreign body fragments had accumulated (Figure 3B). The patient took laxatives and paraffin oil orally every day for the subsequent 3 days after the treatment to improve peristaltic movements of the gastrointestinal tract.

The patient excreted the broken phytobezoar in batches during the following 3 days, with no further phytobezoar excretion on the 4th day. An abdominal CT scan was performed on the 4th day and no intestinal obstruction was present.

Small intestinal bezoar obstruction is a rare disease, accounting for 0.4%-4% of mechanical intestinal obstructions[1]. The early manifestations of the disease are not typical and are easy to misdiagnose. The correct diagnosis usually depends on imaging and endoscopic techniques.

The pathogenesis of bezoars in the small intestine remains unclear. It has been reported that bezoars can form from indigestible food residue. Fruit kernels, peels, fibers, and especially persimmons are related to the formation of phytobezoars[2]. In this case, the patient consumed 5-10 persimmons daily during in-season periods for a long time, and no other predisposing food was identified during the retrospective review. Thus, persimmons might be the reason for the formation of the small intestinal bezoar.

Apart from special dietary factors, gastrointestinal bezoars are often caused by an inducement factor in most patients, such as abdominal surgery or gastrointestinal dysfunction. This patient, for example, had gastroparesis due to diabetes, which affects gastric emptying and can lead to prolonged food retention in the digestive tract, thereby increasing the risk of intestinal obstruction. Patients with diabetes need to pay special attention to their dietary habits. High-fiber foods may help control blood sugar, but can also increase the risk of forming phytobezoars.

There is no doubt that CT is valuable for determining the presence, absence, level, and cause of small bowel obstruc

Double balloon enteroscopy is another safe and useful tool in the diagnosis of small bowel obstruction. In terms of treatment, surgery or laparoscopy interventions are common options[6,7]. Few cases are available in which endoscopy was used for the treatment of small bowel obstruction caused by a phytobezoar. However, patients with diabetes are at an increased risk of infection and delayed wound healing post-surgery, which can influence both surgical decisions and recovery outcomes. Endoscopic fragmentation or removal may be a more appropriate option for treating phytobezoars in diabetes patients. We reviewed previous case reports of similar attempts to treat phytobezoars via endoscopic therapy, among which two cases reported diabetes. In one case, endoscopic treatment was unsuccessful[7]. In another case, the phytobezoar was successfully fragmented, but bowel obstruction recurred, requiring surgery[8]. Endoscopic lithotripsy alone has a certain risk of short-term recurrence, which may be related to diabetes, slowed intestinal peristalsis, and the failure to promptly resolve the bezoar. The patient in this case also has diabetes. Paraffin oil (100 mL) was injected through enteroscopy after endoscopic lithotripsy. A small amount of magnesium sulfate and paraffin oil was admini

The follow up of 2 weeks was performed, and the symptoms did not recur. Sequential catharsis after successful lithotripsy may help expel the bezoar and avoid recurrence. The doctor should be sure that the bezoar is completely expelled from the body, as this represents the appropriate end point of the treatment.

Double balloon enteroscopy combined with sequential laxative therapy is an effective method to treat breakable phytobezoars.

| 1. | Dikicier E, Altintoprak F, Ozkan OV, Yagmurkaya O, Uzunoglu MY. Intestinal obstruction due to phytobezoars: An update. World J Clin Cases. 2015;3:721-726. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 48] [Cited by in RCA: 59] [Article Influence: 5.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Iwamuro M, Okada H, Matsueda K, Inaba T, Kusumoto C, Imagawa A, Yamamoto K. Review of the diagnosis and management of gastrointestinal bezoars. World J Gastrointest Endosc. 2015;7:336-345. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 214] [Cited by in RCA: 199] [Article Influence: 19.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (5)] |

| 3. | Gonzalez-Cordero PL, Vara-Brenes D, Molina-Infante J. An Unusual Cause of Small Bowel Obstruction. Gastroenterology. 2016;150:324-325. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Kim JH, Ha HK, Sohn MJ, Kim AY, Kim TK, Kim PN, Lee MG, Myung SJ, Yang SK, Jung HY, Kim JH. CT findings of phytobezoar associated with small bowel obstruction. Eur Radiol. 2003;13:299-304. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 44] [Cited by in RCA: 54] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Delabrousse E, Lubrano J, Sailley N, Aubry S, Mantion GA, Kastler BA. Small-bowel bezoar versus small-bowel feces: CT evaluation. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2008;191:1465-1468. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Sarofim M, Joseph C, Tsang CLN, Lim CSH, Jaber M. Bezoar due to laxatives: a rare cause of acute small bowel obstruction. ANZ J Surg. 2020;90:1776-1777. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Osada T, Shibuya T, Kodani T, Beppu K, Sakamoto N, Nagahara A, Ohkusa T, Ogihara T, Watanabe S. Obstructing small bowel bezoars due to an agar diet: diagnosis using double balloon enteroscopy. Intern Med. 2008;47:617-620. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Chang CW, Chang CW, Wang HY, Chen MJ, Lin SC, Chang WH, Lee JJ. Intermittent small-bowel obstruction due to a mobile bezoar diagnosed with single-balloon enteroscopy. Endoscopy. 2011;43 Suppl 2 UCTN:E297. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |