Published online Apr 28, 2022. doi: 10.4329/wjr.v14.i4.82

Peer-review started: October 24, 2021

First decision: December 10, 2021

Revised: December 15, 2021

Accepted: March 25, 2022

Article in press: March 25, 2022

Published online: April 28, 2022

Processing time: 182 Days and 21.3 Hours

Sarcopenia is the loss of skeletal muscle mass (SMM) and is a sign of cancer cachexia. Patients with advanced renal cell carcinoma (RCC) may show cachexia.

To evaluate the amount of SMM in male clear cell RCC (ccRCC) patients with and without collateral vessels.

In this study, we included a total of 124 male Caucasian patients divided into two groups: ccRCCa group without collateral vessels (n = 54) and ccRCCp group with collateral vessels (n = 70). Total abdominal muscle area (TAMA) was measured in both groups using a computed tomography imaging-based approach. TAMA measures were also corrected for age in order to rule out age-related effects.

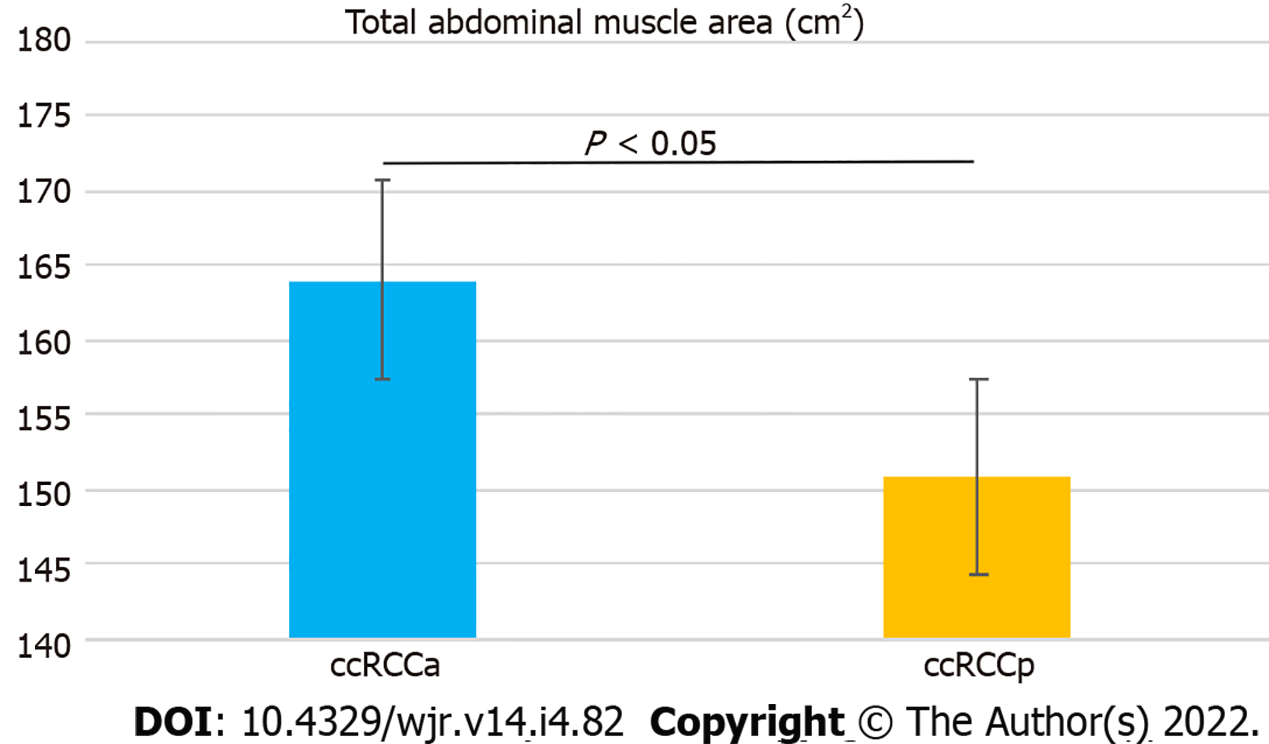

There was a statistically significant difference between the two groups in terms of TAMA (P < 0.05) driven by a reduction in patients with peritumoral collateral vessels. The result was confirmed by repeating the analysis with values corrected for age (P < 0.05), indicating no age effect on our findings.

This study showed a decreased TAMA in ccRCC patients with peritumoral collateral vessels. The presence of peritumoral collateral vessels adjacent to ccRCC might be a fine diagnostic clue to sarcopenia.

Core Tip: Clear cell renal cell carcinoma (ccRCC) can be detected with or without peritumoral collateral vessels. These vessels have been defined as enlarged capsular veins, stimulated by tumor-related effects. The presence of peritumoral collateral vessels around ccRCC is a poorly investigated phenomenon, with unclear clinical meaning. Here, we reported a novel association between peritumoral collateral vessels and loss of skeletal muscle in patients with ccRCC. The effect was not influenced by age, supporting the concept that peritumoral collateral vessels adjacent to ccRCC should drive clinicians’ attention towards cancer cachexia.

- Citation: Greco F, Beomonte Zobel B, Mallio CA. Decreased cross-sectional muscle area in male patients with clear cell renal cell carcinoma and peritumoral collateral vessels. World J Radiol 2022; 14(4): 82-90

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1949-8470/full/v14/i4/82.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4329/wjr.v14.i4.82

Cancer cachexia is the reduction of adipose tissue and skeletal muscle (SM) which cannot be fully compensated with nutrition, resulting in progressive functional impairment[1]. This condition is due to energy disbalance during growth of the neoplasm[2]. Advanced neoplastic diseases can lead to loss of up to 85% of adipose and SM tissues[3]. Cancer cachexia and weight loss influence prognosis and response to therapy[4,5]. Renal cell carcinoma (RCC) patients with an advanced and metastatic disease are susceptible to cachexia. RCC patients have a relatively high prevalence of sarcopenia, the term for loss of SM mass (SMM)[4,6]. For example, sarcopenia was detected in up to 47% of patients with localised RCC and 29%-68% of patients with metastatic RCC[7-9]. Sarcopenic RCC patients have a worse overall survival than RCC patients without sarcopenia[10].

SM is not only part of the locomotor system but also produces and releases cytokines and myokines through the contraction of muscle fibres and thus has endocrine activity[11]. By releasing myokines into the circulation, SM can communicate with other organs such as adipose tissue, bone, the liver, and the brain, underlining the importance of this organ for regulating endocrine balance and decreasing risk of various diseases[12].

Body mass index (BMI) is an indicator used for obesity classification but does not convey information about body composition nor does it provide details about the quantity and distribution of different tissues such as SM and abdominal adipose tissue compartments. For this, computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) are gold standard methods for quantitative assessment and non-invasive tissue characterisation[13-19].

Peritumoural collateral vessels in RCC result from enlargement of capsular renal veins[19]. Gonadal vein recruitment can be present, especially in RCCs located at the lower renal pole[19]. Conversely, lesions located at the upper renal pole have different drainage routes including the adrenal and lower phrenic veins[19]. A study performed on 58 RCC patients reported 28 patients with peritumoural collateral vessels, of which 18 presented with gonadal vein recruitment[19]. Peritumoural collateral vessels with gonadal vein outflow were detected only in RCCs greater than 5 cm in diameter[19].

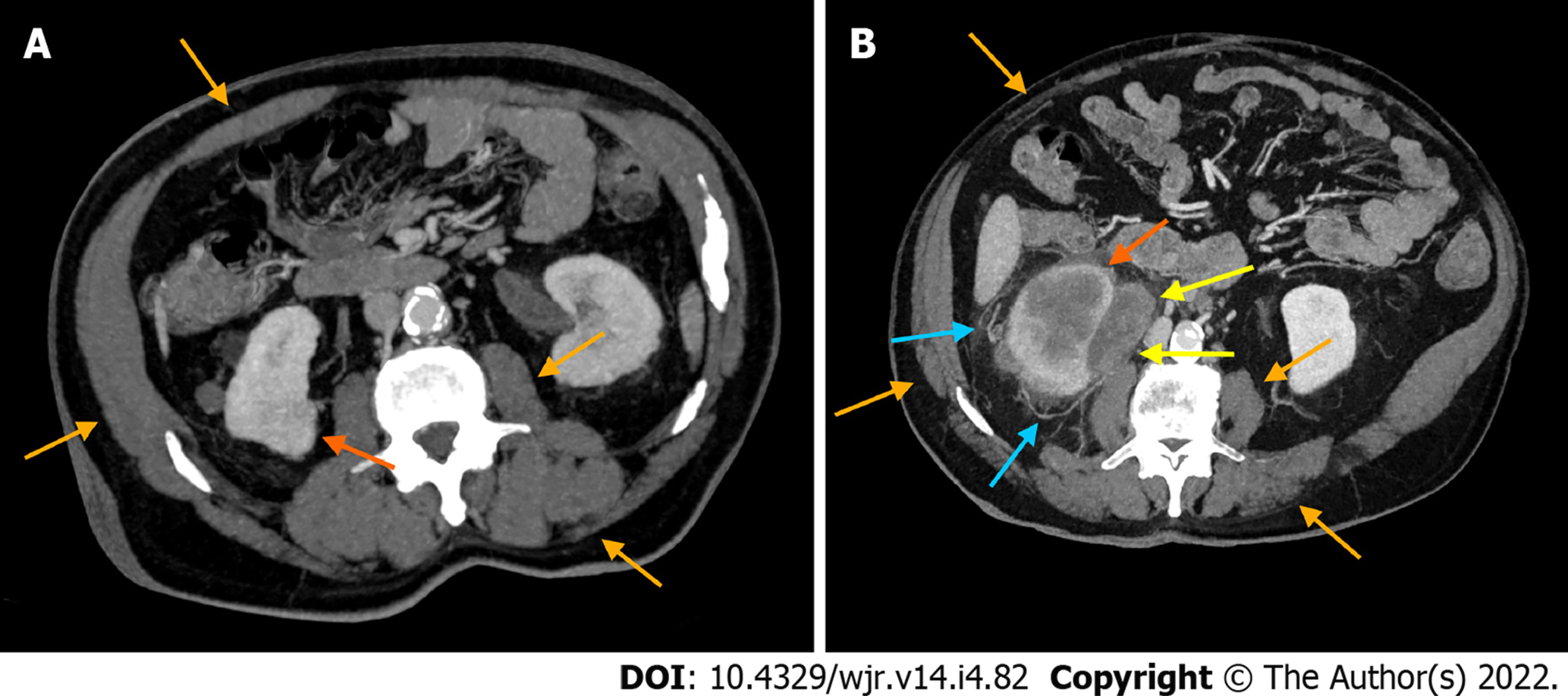

It is reasonable to speculate that increased blood demand due to tumour hypercellularity and neovascularisation, in possible association with main renal vein thrombosis, are factors contributing to the development of peritumoural collateral vessels in RCC patients. Hypercellularity could influence changes in cellular architecture leading to alternative routes of venous outflow that can become macroscopically evident as peritumoural collateral vessels with CT and MRI imaging (Figure 1). The presence of collateral vessels adjacent to RCC is considered a sign of locally advanced disease (i.e., pT stage > T3a)[20]. However, these vessels can also be present in early stages of RCC.

The direct comparison of SMM in clear cell RCC (ccRCC) patients with and without peritumoural collateral vessels has not been performed to date. Evaluating the relationship between peritumoural collateral vessels in ccRCC patients and reductions of SMM would be of clinical interest for prognostic implications. We hypothesised that ccRCC patients would have a decreased cross-sectional total abdominal muscle area (TAMA) and peritumoural collateral vessels as a metabolic systemic consequence of locally advanced disease. To address this question, we evaluated SMM in male ccRCC patients with and without peritumoural collateral vessels using a CT imaging-based approach.

This observational retrospective study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. CT images and data from ccRCC patients with and without peritumoural collateral vessels were downloaded from the Cancer Imaging Archive (TCIA)[21-23]. This data collection received approval from our Institutional Review Board. The subsequent analysis contained publicly available and anonymised data which did not require further review due to previous protections implemented by TCIA. All enrolled subjects signed a written informed consent agreement.

A total of 267 patients with a histologically proven diagnosis of ccRCC were evaluated and selected by examining medical histories and CT images. The exclusion criteria for this study were: Female patients, patients with non-Caucasian ethnicity, patients who had undergone MRI examination only, patients who had undergone chest CT only, heminephrectomised and nephrectomised patients, patients with previous renal ablation, cirrhotic patients with collateral vessels, and patients with a congenital solitary kidney. The selected ccRCC patients were divided into two groups: Absence and presence of collateral vessels (ccRCCa and ccRCCp, respectively).

All ccRCC patients underwent CT examination. Horos v.4.0.0 RC2 software was used for acquisition of TAMA measurements with a semi-automatic function that allowed identification of SM tissue attenuation values (i.e., range 10-40 Hounsfield units)[16]. TAMA (cm2) was defined as the sum of the areas of the abdominal muscles visible on an axial image located 3 cm above the lower margin of L3[16]. This area was measured by selecting a region of interest (ROI) on the following muscles: The rectus abdominis, transversus abdominis, external oblique, quadratus lumborum, iliocostalis lumborum, longissimus thoracis, spinalis thoracis, and psoas major[13]. All ROIs were independently drawn by two radiologists (F.G., 5 years of experience; C.A.M., 9 years of experience) who were blinded to the clinical data. The mean of the two measurements was utilised as the value for each subject.

Data distribution normality was assessed by the Shapiro-Wilk test. Comparison of TAMA between the ccRCCa and ccRCCp groups was performed using the Student’s t-test. To rule out age-related effects, TAMA values were corrected by dividing individual values of TAMA by the age of each subject. Sub-analyses for TAMA assessment were performed by Student’s t-tests between ccRCC patients with low (I/II) or high (III/IV) Fuhrman grade and between patients that were alive or deceased at the time of data collection. To evaluate the reliability of measurements by the two radiologists, the intraclass correlation coefficient for the TAMA measurements was calculated using Cronbach’s alpha (also known as coefficient alpha). Finally, Kaplan-Meier curves were included to assess survival of the ccRCCa and ccRCCp groups. The threshold of statistical significance was established at P < 0.05.

A total of 124 male Caucasian ccRCC patients were selected according to the exclusion criteria. The two groups were composed as follows: ccRCCa (n = 54; mean age: 57, range: 26-83) and ccRCCp (n = 70; mean age: 59.8, range: 34-84). The staging of ccRCCa group patients were as follows: 1 T1N0M0, 8 T1aN0M0, 21 T1aNxM0, 6 T1bN0M0, 7 T1bNxM0, 1 T1bNxM1, 3 T2N0M0, 1 T2NxM0, 2 T3aN0M0, 2 T3aN0M1, 1 T3bN0M0, and 1 T3bNxM0. The staging of ccRCCp group patients were as follows: 10 T1aNxM0, 1 T1aNxM0, 1 T1aN1M0, 2 T1bN0M0, 8 T1bNxM0, 5 T2N0M0, 1 T2N0M1, 4 T2NxM0, 2 T2aNxM0, 1 T2bN0M0, 9 T3aN0M0, 1 T3aN0M1, 5 T3aNxM0, 1 T3aN0M1, 8 T3aNxM1, 1 T3aN1M1, 3 T3bN0M0, 4 T3bNxM0, 1 T3bNxM1, 1 T4NxM0, and 1 T4N1M1.

Only three (2.41%) of 124 patients had renal vein thrombosis and these three were included in the ccRCCp group (4.28% of ccRCCp patients). No patients had segmental renal vein thrombosis. All patients of the ccRCCp group (n = 70; 100%) showed an exophytic growth pattern. In addition, 31.42% of ccRCCp patients had T1 stage (n = 22), 18.57% T2 (n = 13), 47.14% T3 (n = 33), and 2.85% T4 (n = 2). A total of 28 patients had a history of previous malignancy and 11 patients received a neoadjuvant treatment.

No significant difference was detected in the ages of the two groups (P = 0.21). A statistically significant difference between the ccRCCa and ccRCCp groups was obtained for TAMA (P < 0.05). These results are summarised in Table 1 and represented in Figure 2. Examples of CT cases showing the observed effect are shown in Figure 3. Statistically significant differences between the ccRCCa and ccRCCp groups were confirmed after TAMA values were corrected for age (P < 0.05) (Table 1).

| TAMA (cm2) | TAMA_C (cm2) | |

| ccRCCa group (mean, range, and SD) | 164.02 (91, 233.5 ± 31.86) | 3.08 (1.29, 5.83 ± 1.06) |

| ccRCCp group (mean, range, and standard deviation) | 150.91 (76.3, 218.3 ± 30.34) | 2.67 (1, 4.67 ± 0.91) |

| P | 0.02 | 0.02 |

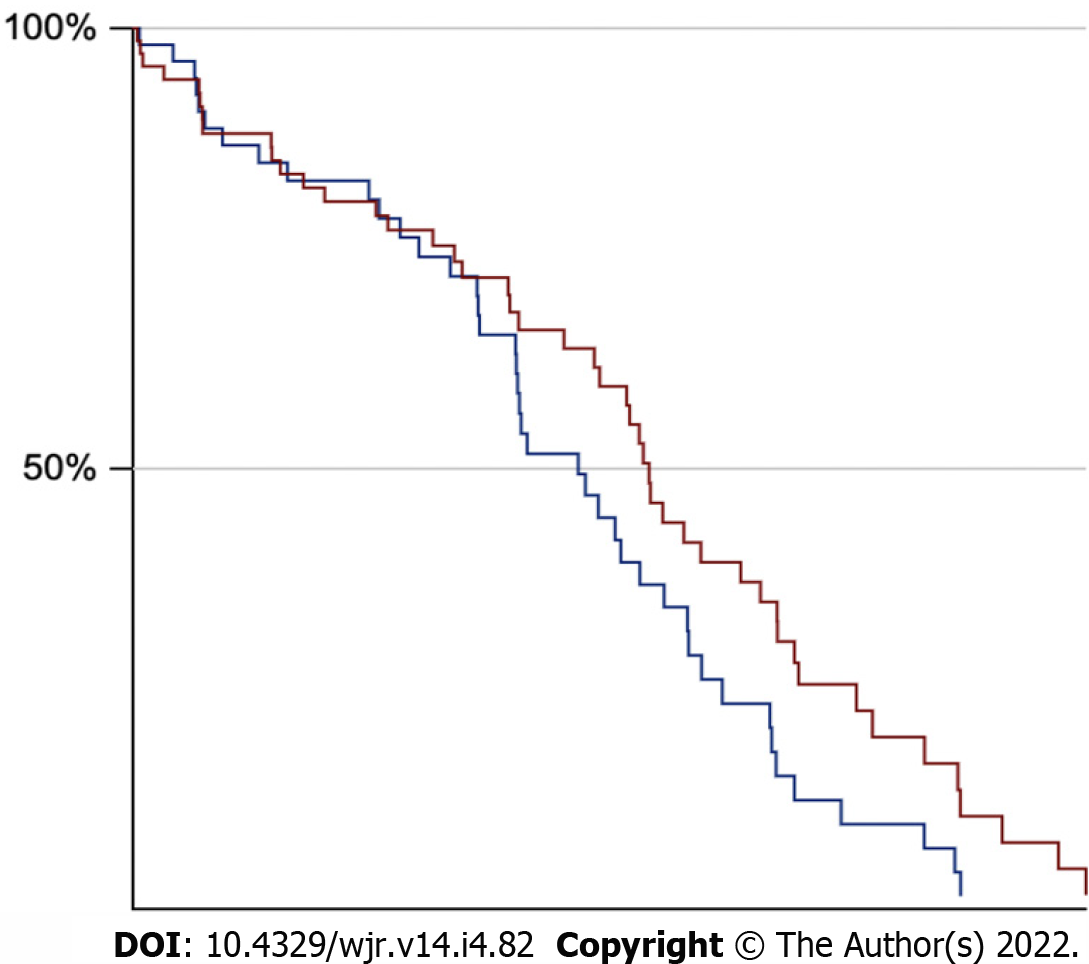

No statistically significant differences (P = 0.66) were found between ccRCC patients with low (n = 44; 1 grade I and 43 grade II) and high (n = 80; 61 grade III and 19 grade IV) Fuhrman grades. These results are summarised in Table 2. Patients who were deceased (n = 33) at the time of data collection demonstrated a statistically significant reduction (P < 0.001) of TAMA in comparison to those that were still alive (n = 90) (Table 3). Cronbach’s alpha of the two tracers was 0.913, indicating excellent reliability. No significant differences in survival between the two groups (available data for 54 of 54 ccRCCa patients and 69 of 70 ccRCCp patients) were found based on the Kaplan-Meier method (log-rank test: Z = 1.88, P = 0.06) (Figure 4).

| TAMA (cm2) | |

| ccRCC patients with low fuhrman grade (I/II) (mean, range, and standard deviation) | 158.27 (83.2-233.5), 35.41 |

| ccRCC patients with high Fuhrman grade (III/IV) (mean, range, and standard deviation) | 155.71 (76.3-219.2), 29.44 |

| P | 0.66 |

| TAMA (cm2) | |

| Alive ccRCC patients | 162.02 |

| (mean, range, and standard deviation) | 91, 233.5 ± 28.42 |

| Dead ccRCC patients | 150.91 |

| (mean, range, and standard deviation) | 76.3, 219.2 ± 34.84 |

| P | 0.0008 |

This study showed a significant decrease of SMM in the ccRCCp patient group compared to the ccRCCa group. Although SMM is expected to decrease with age, we did not find a significant difference between the ccRCCa and ccRCCp groups in terms of age. This finding was supported by analysis of age-corrected TAMA values. Since differences in SMM can segregate according to gender and ethnicity, only male Caucasian patients were included in the present study to eliminate these potentially confounding factors[24,25].

It has been hypothesised that contraction of myofibres can affect metabolism by triggering the release of humoral/exercise factors from SM which signal for an increase in glucose demand from distant organs[26]. The concept of humoral factors has been progressively developed since cytokine interleukin 6 (IL-6) was found to increase in response to physical exercise causing both autocrine and endocrine effects[27,28].

The cytokines and other peptides produced, expressed, and secreted by SM are called myokines. This term, suggested by Pederson et al[29], derives from the Greek words for "muscle" and "motion" and refers to such molecules that exert an endocrine effect on the human body. The physiological consequences of autocrine and paracrine action of myokines includes regulation of muscle growth and lipid metabolism. For example, the myokines produced during exercise, including IL-6, IL-7, IL-15, irisin, and leukaemia inhibitory factor, determine muscle growth by stimulating protein synthesis and hypertrophy. Conversely, myostatin, a member of the transforming growth factor β (TGF-β) superfamily, causes muscle atrophy[30,31]. Activin A, another member of TGF-β superfamily, reproduces the same action of myostatin on SM[30]. Increased blood levels of activin A is known to reduce muscle strength and has been positively correlated with cachexia in cancer patients[32].

Factors that can distort tumour extension such as peritumoural inflammation or the presence of a secondary pseudocapsule can reduce the effectiveness of CT in distinguishing T1 and T2 stages from T3a[19,33]. Incorrect staging, in fact, was detected in 27 of 94 tumours in a study of RCC patients using cross-sectional imaging[19]. Peritumoural collateral vessels in RCC patients showed a specificity of 94% and positive predictive value of 88% in staging of locally advance disease by cross-sectional CT imaging[19].

In our study, 100% of the patients from the ccRCCp group exhibited an exophytic growth pattern. This novel finding suggests a link between peritumour collateral vessels and the RCC growth pattern. Body composition imaging has gained an important role in the assessment of oncological risk, pathogenesis, and development of RCC[14-17]. CT imaging features of the tumour can also provide indications about the patient's body composition. In the present study, the peritumoural collateral vessels adjacent to the ccRCC was associated with a reduction of SMM, a possible sign of sarcopenia. Most likely, in ccRCCp patients, locally advanced disease determines muscle trophism loss as compared to ccRCCa patients. The progressive SMM reduction assessed by CT could be considered a sign of sarcopenia, and therefore of cancer cachexia, with potential prognostic implication for patients. Indeed, deceased ccRCC patients demonstrated a statistically significant reduction of TAMA relative to live patients, suggesting a link between sarcopenia and survival in our sample. However, Kaplan-Maier curves showed a difference just above the statistical threshold between the ccRCCa and ccRCCp patient groups.

The results of this study are supported by recent evidence showing a significant reduction of subcutaneous adipose tissue in ccRCC patients with peritumoural collateral vessels[17]. The limitations of this study include the retrospective study design which did not allow us to assess detailed clinical and anamnestic data including occupation, BMI, hormone blood levels, disease-free survival, timing of CT imaging, performing status, therapies, and CT follow-up after treatment. For instance, testosterone deficiency is known to be associated with an increase in proinflammatory cytokines. Inclusion of hormonal data, such as testosterone levels, could help better understand the cytokine cascade that is associated with pathogenesis and changes in body composition[34,35]. Similarly, CT follow-up after treatment (e.g., surgery or chemotherapy/targeted immunotherapy) would have been helpful to understand changes in the sarcopenia index and the relationship with peritumoural collateral vessels after treatment. The vendor, model, and acquisition parameters (such as slice thickness) of the CT imaging used in this study were also unavailable. Images from the open-source TCIA were often acquired heterogeneously at multiple centres as part of clinical routine. A larger sample size would have strengthened our multivariate assessment of whether collateral vessels are an independent predictor of sarcopenia as well as the potential impact of other variables such as staging[36-38].

Further studies are needed to evaluate sarcopenia index changes after treatment to add robustness to the role of peritumoural collateral vessels as a prognostic biomarker for ccRCC patients. Such studies should consider abdominal circumference and patients’ occupation, which is a factor that can influence SMM (for example, people who are engaged in heavy physical labour would be expected to have significantly more muscle mass compared to office workers)[39]. Finally, SMM content of other subtypes of kidney cancer (e.g., chromophobe and papillary) or other categories of cancer patients should be evaluated to assess the impact of SMM trophism on a patient's health status and prognosis.

This study showed a reduction of SMM in ccRCC patients with peritumoural collateral vessels. The presence of peritumoural collateral vessels adjacent to ccRCC is a good candidate biomarker for sarcopenia and therefore of cancer cachexia.

Sarcopenia is the loss of skeletal muscle mass (SMM) and is part of cancer cachexia in which there is a decrease of adipose tissue and SM. Peritumoral collateral vessels adjacent to renal cell carcinoma (RCC) are indicative of locally advanced disease.

Metabolic systemic consequence related to a locally advanced disease might be linked to a decrease of SSM in clear cell RCC (ccRCC) patients with peritumoral collateral vessels, possibly providing clinically relevant information.

The aim of this study was to evaluate the amount of SMM in male ccRCC patients with and without peritumoral collateral vessels, in order to understand a possible relationship between sarcopenia and collateral vessels.

In this study, we included a total of 124 male Caucasian patients divided into two groups: ccRCCa (n = 54) and ccRCCp (n = 70) groups, respectively, without and with collateral vessels. Computed tomography imaging-based approach was used for total abdominal muscle area (TAMA) mea

There was a statistically significant difference between the two groups for TAMA (P < 0.05).

This study showed a reduction of TAMA in male ccRCC patients with peritumoral collateral vessels.

Further studies, on larger sample size and with longitudinal data, will shed light on collateral vessels adjacent to RCC as a possible biomarker of cachexia and sarcopenia.

Provenance and peer review: Invited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Radiology, nuclear medicine and medical imaging

Country/Territory of origin: Italy

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C, C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): E

P-Reviewer: Iida H, Japan; Lin X, China; Sato H, Japan S-Editor: Ma YJ L-Editor: Wang TQ P-Editor: Ma YJ

| 1. | Tisdale MJ. Mechanisms of cancer cachexia. Physiol Rev. 2009;89:381-410. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 789] [Cited by in RCA: 830] [Article Influence: 51.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Daas SI, Rizeq BR, Nasrallah GK. Adipose tissue dysfunction in cancer cachexia. J Cell Physiol. 2018;234:13-22. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 104] [Cited by in RCA: 101] [Article Influence: 14.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Murphy RA, Wilke MS, Perrine M, Pawlowicz M, Mourtzakis M, Lieffers JR, Maneshgar M, Bruera E, Clandinin MT, Baracos VE, Mazurak VC. Loss of adipose tissue and plasma phospholipids: relationship to survival in advanced cancer patients. Clin Nutr. 2010;29:482-487. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 94] [Cited by in RCA: 112] [Article Influence: 7.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Semeniuk-Wojtaś A, Lubas A, Stec R, Syryło T, Niemczyk S, Szczylik C. Neutrophil-to-lymphocyte Ratio, Platelet-to-lymphocyte Ratio, and C-reactive Protein as New and Simple Prognostic Factors in Patients With Metastatic Renal Cell Cancer Treated With Tyrosine Kinase Inhibitors: A Systemic Review and Meta-analysis. Clin Genitourin Cancer. 2018;16:e685-e693. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 42] [Cited by in RCA: 64] [Article Influence: 9.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Blum D, Stene GB, Solheim TS, Fayers P, Hjermstad MJ, Baracos VE, Fearon K, Strasser F, Kaasa S; Euro-Impact. Validation of the Consensus-Definition for Cancer Cachexia and evaluation of a classification model--a study based on data from an international multicentre project (EPCRC-CSA). Ann Oncol. 2014;25:1635-1642. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 158] [Cited by in RCA: 187] [Article Influence: 17.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Martin L, Birdsell L, Macdonald N, Reiman T, Clandinin MT, McCargar LJ, Murphy R, Ghosh S, Sawyer MB, Baracos VE. Cancer cachexia in the age of obesity: skeletal muscle depletion is a powerful prognostic factor, independent of body mass index. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31:1539-1547. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1436] [Cited by in RCA: 1512] [Article Influence: 126.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Psutka SP, Boorjian SA, Moynagh MR, Schmit GD, Costello BA, Thompson RH, Stewart-Merrill SB, Lohse CM, Cheville JC, Leibovich BC, Tollefson MK. Decreased Skeletal Muscle Mass is Associated with an Increased Risk of Mortality after Radical Nephrectomy for Localized Renal Cell Cancer. J Urol. 2016;195:270-276. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 75] [Cited by in RCA: 100] [Article Influence: 11.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Sharma P, Zargar-Shoshtari K, Caracciolo JT, Fishman M, Poch MA, Pow-Sang J, Sexton WJ, Spiess PE. Sarcopenia as a predictor of overall survival after cytoreductive nephrectomy for metastatic renal cell carcinoma. Urol Oncol. 2015;33:339.e17-339.e23. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 63] [Cited by in RCA: 92] [Article Influence: 9.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Fukushima H, Nakanishi Y, Kataoka M, Tobisu K, Koga F. Prognostic Significance of Sarcopenia in Patients with Metastatic Renal Cell Carcinoma. J Urol. 2016;195:26-32. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 72] [Cited by in RCA: 91] [Article Influence: 10.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Hu X, Liao DW, Yang ZQ, Yang WX, Xiong SC, Li X. Sarcopenia predicts prognosis of patients with renal cell carcinoma: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int Braz J Urol. 2020;46:705-715. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 5.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Pedersen BK. Muscle as a secretory organ. Compr Physiol. 2013;3:1337-1362. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 275] [Cited by in RCA: 345] [Article Influence: 28.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Pedersen L, Hojman P. Muscle-to-organ cross talk mediated by myokines. Adipocyte. 2012;1:164-167. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 81] [Cited by in RCA: 95] [Article Influence: 7.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Prado CM, Heymsfield SB. Lean tissue imaging: a new era for nutritional assessment and intervention. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr. 2014;38:940-953. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 336] [Cited by in RCA: 412] [Article Influence: 37.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Greco F, Mallio CA, Grippo R, Messina L, Vallese S, Rabitti C, Quarta LG, Grasso RF, Beomonte Zobel B. Increased visceral adipose tissue in male patients with non-clear cell renal cell carcinoma. Radiol Med. 2020;125:538-543. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 4.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Greco F, Quarta LG, Grasso RF, Beomonte Zobel B, Mallio CA. Increased visceral adipose tissue in clear cell renal cell carcinoma with and without peritumoral collateral vessels. Br J Radiol. 2020;93:20200334. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 4.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Greco F, Mallio CA. Relationship between visceral adipose tissue and genetic mutations (VHL and KDM5C) in clear cell renal cell carcinoma. Radiol Med. 2021;126:645-651. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 6.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Greco F, Quarta LG, Carnevale A, Giganti M, Grasso RF, Beomonte Zobel B, Mallio CA. Subcutaneous Adipose Tissue Reduction in Patients with Clear Cell Renal Cell Carcinoma and Peritumoral Collateral Vessels: A Retrospective Observational Study. Appl Sci. 2021;11:6076. |

| 18. | Greco F, Faiella E, Santucci D, Mallio CA, Nezzo M, Quattrocchi CC, Beomonte Zobel B, Grasso RF. Imaging of Renal Medullary Carcinoma. J Kidney Cancer VHL. 2017 4:1-7. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Murphy BL, Gaa J, Papanicolaou N, Lee MJ. Gonadal vein recruitment in renal cell carcinoma: incidence, pathogenesis and clinical significance. Clin Radiol. 1996;51:797-800. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Bradley AJ, MacDonald L, Whiteside S, Johnson RJ, Ramani VA. Accuracy of preoperative CT T staging of renal cell carcinoma: which features predict advanced stage? Clin Radiol. 2015;70:822-829. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | NIH National Cancer Institute. Available from: https://cancergenome.nih.gov/. |

| 22. | Akin O, Elnajjar P, Heller M, Jarosz R, Erickson B, Kirk S, Lineham M, Gautam R, Vikram R, Garcia KM, Roche C, Bonaccio E, Filippini J. Radiology Data from The Cancer Genome Atlas Kidney Renal Clear Cell Carcinoma [TCGA-KIRC] collection. The Cancer Imaging Archive 2016. |

| 23. | Clark K, Vendt B, Smith K, Freymann J, Kirby J, Koppel P, Moore S, Phillips S, Maffitt D, Pringle M, Tarbox L, Prior F. The Cancer Imaging Archive (TCIA): maintaining and operating a public information repository. J Digit Imaging. 2013;26:1045-1057. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2828] [Cited by in RCA: 2157] [Article Influence: 179.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Janssen I, Heymsfield SB, Wang ZM, Ross R. Skeletal muscle mass and distribution in 468 men and women aged 18-88 yr. J Appl Physiol (1985). 2000;89:81-88. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1672] [Cited by in RCA: 1918] [Article Influence: 76.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Silva AM, Shen W, Heo M, Gallagher D, Wang Z, Sardinha LB, Heymsfield SB. Ethnicity-related skeletal muscle differences across the lifespan. Am J Hum Biol. 2010;22:76-82. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 217] [Cited by in RCA: 191] [Article Influence: 12.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Goldstein MS. Humoral nature of the hypoglycemic factor of muscular work. Diabetes. 1961;10:232-234. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 67] [Cited by in RCA: 66] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Ostrowski K, Rohde T, Zacho M, Asp S, Pedersen BK. Evidence that interleukin-6 is produced in human skeletal muscle during prolonged running. J Physiol. 1998;508 ( Pt 3):949-953. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 456] [Cited by in RCA: 475] [Article Influence: 17.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Steensberg A, van Hall G, Osada T, Sacchetti M, Saltin B, Klarlund Pedersen B. Production of interleukin-6 in contracting human skeletal muscles can account for the exercise-induced increase in plasma interleukin-6. J Physiol. 2000;529:237-242. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 645] [Cited by in RCA: 722] [Article Influence: 28.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Pedersen BK, Steensberg A, Fischer C, Keller C, Keller P, Plomgaard P, Febbraio M, Saltin B. Searching for the exercise factor: is IL-6 a candidate? J Muscle Res Cell Motil. 2003;24:113-119. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 322] [Cited by in RCA: 368] [Article Influence: 16.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Deshmukh AS, Cox J, Jensen LJ, Meissner F, Mann M. Secretome Analysis of Lipid-Induced Insulin Resistance in Skeletal Muscle Cells by a Combined Experimental and Bioinformatics Workflow. J Proteome Res. 2015;14:4885-4895. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 51] [Cited by in RCA: 57] [Article Influence: 5.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Grube L, Dellen R, Kruse F, Schwender H, Stühler K, Poschmann G. Mining the Secretome of C2C12 Muscle Cells: Data Dependent Experimental Approach To Analyze Protein Secretion Using Label-Free Quantification and Peptide Based Analysis. J Proteome Res. 2018;17:879-890. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 40] [Cited by in RCA: 56] [Article Influence: 8.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Loumaye A, de Barsy M, Nachit M, Lause P, Frateur L, van Maanen A, Trefois P, Gruson D, Thissen JP. Role of Activin A and myostatin in human cancer cachexia. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2015;100:2030-2038. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 133] [Cited by in RCA: 162] [Article Influence: 16.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Frank I, Blute ML, Cheville JC, Lohse CM, Weaver AL, Zincke H. An outcome prediction model for patients with clear cell renal cell carcinoma treated with radical nephrectomy based on tumor stage, size, grade and necrosis: the SSIGN score. J Urol. 2002;168:2395-2400. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 284] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Ficarra V, Galfano A, Mancini M, Martignoni G, Artibani W. TNM staging system for renal-cell carcinoma: current status and future perspectives. Lancet Oncol. 2007;8:554-558. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 68] [Cited by in RCA: 79] [Article Influence: 4.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Mohamad NV, Wong SK, Wan Hasan WN, Jolly JJ, Nur-Farhana MF, Ima-Nirwana S, Chin KY. The relationship between circulating testosterone and inflammatory cytokines in men. Aging Male. 2019;22:129-140. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 132] [Cited by in RCA: 202] [Article Influence: 33.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Gu W, Wu J, Liu X, Zhang H, Shi G, Zhu Y, Ye D. Early skeletal muscle loss during target therapy is a prognostic biomarker in metastatic renal cell carcinoma patients. Sci Rep. 2017;7:7587. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Choi Y, Oh DY, Kim TY, Lee KH, Han SW, Im SA, Bang YJ. Skeletal Muscle Depletion Predicts the Prognosis of Patients with Advanced Pancreatic Cancer Undergoing Palliative Chemotherapy, Independent of Body Mass Index. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0139749. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 198] [Cited by in RCA: 195] [Article Influence: 19.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | Sato H, Goto T, Hayashi A, Kawabata H, Okada T, Takauji S, Sasajima J, Enomoto K, Fujiya M, Oyama K, Ono Y, Sugitani A, Mizukami Y, Okumura T. Prognostic significance of skeletal muscle decrease in unresectable pancreatic cancer: Survival analysis using the Weibull exponential distribution model. Pancreatology. 2021;21:892-902. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | Fang H, Berg E, Cheng X, Shen W. How to best assess abdominal obesity. Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care. 2018;21:360-365. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 96] [Cited by in RCA: 175] [Article Influence: 25.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |