Published online Sep 26, 2017. doi: 10.4330/wjc.v9.i9.737

Peer-review started: January 16, 2017

First decision: April 27, 2017

Revised: July 6, 2017

Accepted: July 21, 2017

Article in press: July 24, 2017

Published online: September 26, 2017

Processing time: 255 Days and 9.7 Hours

Patients with a Brugada type 1 electrocardiogram (ECG) pattern may suffer sudden cardiac death (SCD). Recognized risk factors are spontaneous type 1 ECG and syncope of presumed arrhythmic origin. Familial sudden cardiac death (f-SCD) is not a recognized independent risk factor. Finally, positive electrophysiologic study (+EPS) has a controversial prognostic value. Current ESC guidelines recommend implantable cardioverter defibrillator (ICD) implantation in patients with a Brugada type 1 ECG pattern if they have suffered a previous resuscitated cardiac arrest (class I recommendation) or if they have syncope of presumed cardiac origin (class IIa recommendation). In clinical practice, however, many other patients undergo ICD implantation despite the suggestions of the guidelines. In a 2014 cumulative analysis of the largest available studies (including over 2000 patients), we found that 1/3 of patients received an ICD in primary prevention. Interestingly, 55% of these latter were asymptomatic, while 80% had a + EPS. This means that over 30% of subjects with a Brugada type 1 ECG pattern were considered at high risk of SCD mainly on the basis of EPS, to which a class IIb indication for ICD is assigned by the current ESC guidelines. Follow-up data confirm that in clinical practice single, and often frail, risk factors overestimate the real risk in subjects with the Brugada type 1 ECG pattern. We can argue that, in clinical practice, many cardiology centers adopt an aggressive treatment in subjects with a Brugada type 1 ECG pattern who are not at high risk. As a result, many healthy persons may be treated in order to save a few patients with a true Brugada Syndrome. Better risk stratification is needed. A multi-parametric approach that considers the contemporary presence of multiple risk factors is a promising one.

Core tip: On the basis of frail risk factors, many cardiology centers adopt an aggressive treatment in subjects with a Brugada type 1 electrocardiogram pattern who are not at high risk. As a result, many healthy persons may be treated in order to save a few patients with a true Brugada Syndrome. Better risk stratification is needed, for example the adoption of a multiparametric approach.

- Citation: Delise P, Allocca G, Sitta N. Brugada type 1 electrocardiogram: Should we treat the electrocardiogram or the patient? World J Cardiol 2017; 9(9): 737-741

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1949-8462/full/v9/i9/737.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4330/wjc.v9.i9.737

Brugada syndrome was first described by the Brugada brothers in 1992[1] as a distinct heritable clinical entity characterized by malignant arrhythmias in patients without organic heart disease and by a peculiar electrocardiogram (ECG) pattern consisting of coved-type ST elevation ≥ 2 mm in one or more leads from V1 to V3 (Brugada type 1 ECG pattern).

During the last 25 years, both in scientific papers and in current practice, the terms “Brugada type 1 ECG pattern” and “Brugada Syndrome” have frequently been used synonymously. Even the recent ESC guidelines on the prevention of sudden cardiac death (SCD)[2] equate the Brugada type 1 ECG pattern with Brugada Syndrome, basing the diagnosis of Brugada syndrome only on ECG criteria. This is, to say the least, curious, as the definition of any syndrome includes symptoms and various clinical and instrumental signs.

This semantic error has the deleterious consequence that any subject with a Brugada type 1 ECG pattern is considered to be at risk of SCD, both in the presence and in the absence of symptomatic or asymptomatic arrhythmias.

In medicine, similar mistakes have been made many times in the past when an ECG sign has been equated to a disease. For example, more than 60 years ago, negative T waves were defined by the Mexican School[3] as “ischemia”, and this ECG anomaly was identified with coronary artery disease. This error was corrected only after many years, when it was demonstrated that negative T waves were not always a manifestation of myocardial ischemia; rather, they may be a nonspecific finding or may be due to various heart diseases (hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy, pulmonary embolism, etc.).

Likewise, a so-called Brugada type 1 ECG pattern, in addition to indicating a Brugada syndrome, may be a nonspecific, benign finding or the consequence of a right ventricular cardiomyopathy[4], pulmonary embolism, etc. (Brugada phenocopies)[5].

It follows that “Brugada type 1 ECG pattern” and “Brugada syndrome” should not be used as synonyms, even though, in the presence of a Brugada type 1 ECG, a Brugada syndrome in its asymptomatic phase may be suspected.

Current ESC guidelines[2] recommend implantable cardioverter defibrillator (ICD) implantation in patients with a Brugada type 1 ECG pattern if they have suffered a previous resuscitated cardiac arrest (class I recommendation) or if they have syncope of presumed cardiac origin (class IIa recommendation). In clinical practice, however, many other patients undergo ICD implantation despite the suggestions of the guidelines.

In 2014, Delise et al[6] performed a cumulative analysis of the largest available studies[7-16], which included a total of 2176 patients with a Brugada type 1 ECG pattern who had no history of cardiac arrest. In this study, we found that 1/3 of patients received an ICD in primary prevention.

In addition, our cumulative data[6] (Table 1) show that, frequently in clinical practice, indications for ICD implantation not only do not completely follow current guidelines, but also do not fully consider the weight of the various potential risk factors. Indeed, recognized risk factors are spontaneous type 1 ECG and syncope of presumed arrhythmic origin. In contrast, a drug-induced type 1 ECG pattern and the absence of symptoms identify a low risk[12-21]. Familial SCD is not a recognized independent risk factor[16,17,20]. Finally, +EPS has a controversial prognostic value[11,12,17,19,20].

| Studies | n. pts | Spont. type 1 ECG | Drug-I type 1 ECG | Fam. SCD | Syncope | Asympt. | +EPS/EPS performed |

| Sacher et al[8] | 202 | 61% (124) | 49% (78) | 42% (85) | 35% (70) | 65% (132) | 82% (153/187) |

| Kamakura et al[9] | 70 | 66% (44) | 34% (26) | 23% (16) | 46% (32) | 54% (38) | 87% (58/67) |

| Sarkozy et al[10] | 47 | 62% (29) | 38% (18) | 55% (26) | 55% (26) | 45% (21) | 83% (38/46) |

| Delise et al[11] | 110 | 74% (82) | 26% (28) | 38% (42) | 58% (64) | 42% | 85% (90/106) |

| Priori et al[12] | 137 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | 72% (98/137) |

| Total | 566 | 65% (279/429) | 35% (150/429) | 39% (169/429) | 45% (192/429) | 65% (237/429) | 80% (437/543) |

Interestingly, in our cumulative analysis[6], of 566 patients who received an ICD in primary prevention, only 45% were symptomatic for syncope. In addition 65% had a spontaneous Brugada type 1 ECG pattern, while 35% had a drug-induced Brugada type 1 ECG. In contrast, 80% had a positive EPS (Table 1). In other words, ICD indication was mainly guided by EPS, to which a class IIb indication for ICD is assigned by the current ESC guidelines[2].

Further data come from a recent paper by Conte et al[17], of the Group of Pedro Brugada, who published their 20-year single-center experience of ICD implantation in patients with Brugada ECG pattern/syndrome. In this population, 151 patients received an ICD in primary prevention, 30% of whom were asymptomatic. In these 30 asymptomatic patients, the indication for ICD was mainly guided by a family history of Brugada syndrome (59%), f-SCD (59%) and +EPS (61%). Of note, the vast majority (76%) had a drug-induced type 1 ECG.

The main reason why many cardiologists do not follow guidelines and overestimate the risk of subjects with a Brugada type 1 ECG pattern stems from the frail scientific basis of currently used risk factors. Indeed, all prospective studies (ours included) which have evaluated risk factors have been based on population registries[6]. Furthermore, all these studies have evaluated a combined end-point constituted by fast ventricular arrhythmias (FVA) recorded by ICD, and by SCD in subjects without ICD[6]. However, ICD-recorded FVA are only a surrogate of SCD[22,23], as FVA are frequently self-terminating and do not necessarily lead to SCD. It follows that, in all these studies, any single risk factor probably overestimates the real risk of SCD.

In addition, all recognized and possible risk factors (spontaneous type 1 ECG, syncope, familial SD, +EPS), when tested singly against recorded FVA in patients with ICD, show an unsatisfactory performance: Variable sensitivity (ranging from 39% to 86%), low specificity (21%-61%) and low positive predictive value (ranging from 9% to 15%)[6].

As all prospective studies have evaluated a combined end-point constituted by fast ventricular arrhythmias (FVA) recorded by ICD, and sudden death (SD) in subjects without ICD[6], it is impossible to say what the outcome of patients would be if they did not undergo ICD implantation. Indeed, no randomized studies have been performed that are able to establish the real risk of SCD and the ability of ICD to prevent it.

Despite these limitations, most prospective studies have shown that, in general, the risk of arrhythmias is low in asymptomatic patients, in those with drug-induced type 1 ECG and in those with negative EPS[6-17]. For example, in the study by Conte et al[17], asymptomatic patients with ICD in primary prevention had an incidence of appropriate shocks of only 0.16 per year.

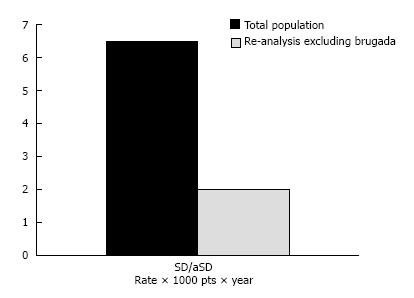

No prospective study has focused on the risk of SCD in patients without ICD. However, in our cumulative analysis[6], we also analyzed 1366 patients without ICD separately. These patients were generally asymptomatic (84%) and did not have familial SCD (82%); about half (54%) had a spontaneous and about half (46%) a drug-induced type 1 ECG. EPS was positive in only 22%. In other words, most of them were correctly classified as being at low risk according to the guidelines. In these patients, SCD occurred in 6.5 per 1000 patients per year.

In a subsequent re-analysis of this population[24], we excluded the 2003 paper by Brugada, because his population had a much higher risk than those of the remaining authors (high prevalence of familial SD, multiple risk factors, three-fold higher incidence of SCD). In this re-analysis, the incidence of SCD fell to 2 per 1000 patients per year (Figure 1). We can argue that patients classified as being at low risk according to the guidelines generally have a benign outcome.

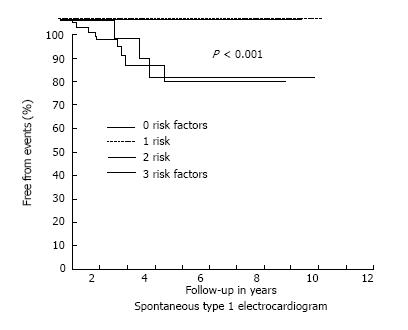

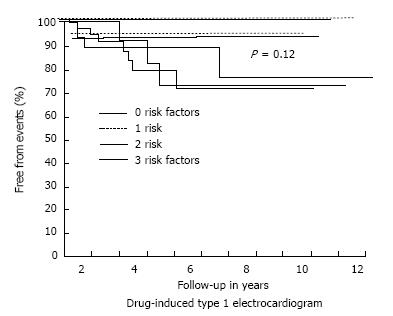

In 2011, our group[11] suggested that selecting patients on the basis of the presence of single or multiple risk factors could better stratify the risk of events. Specifically, on considering f-SCD, syncope and +EPS as risk factors, we found that, during follow-up, no events occurred in patients with either 0 or 1 risk factor, while events occurred only in patients with 2 or 3 risk factors. This was observed whether the patients had a spontaneous or a drug-induced Brugada type 1 ECG (Figures 2 and 3). Similar results were reported by Okamura et al[25] in 2015.

Recently, Sieira et al[26], from Pedro Brugada’s group, proposed a score model to predict the risk of events in patients with Brugada Syndrome. The model includes several risk factors: Spontaneous type 1 ECG (1 point), early f-SCD (1 point), +EPS (2 points), syncope (2 points), sinus node dysfunction (3 points) and previous aborted SCD (4 points). Interestingly, in line with our data, a significantly increased risk was observed in subjects with more than 2 points.

In current clinical practice, many cardiology centers adopt an aggressive treatment in subjects with a Brugada type 1 ECG pattern who are not at high risk. Thus, these subjects undergo ICD implantation or experimental therapies such as ablation of the right ventricular outflow tract[27,28]. As a result, many healthy persons may be treated in order to save a few patients with a true Brugada Syndrome. The consequences of such a policy are deleterious in terms of the psychological impact on the subjects treated, the procedural risks involved and the costs accruing to the community.

The solution to this problem is not easy. However, it is reasonable to restrict indications only to high-risk patients, as indicated by the guidelines. Moreover, in addition to the indications provided in the guidelines, ICD implantation might be reasonable in subjects with multiple risk factors[11,25,26]. Finally, in controversial cases and/or in cases at low risk, it is a good rule to discuss indications, contraindications and complications with patients and their families, so that they are aware that there is still a risk, even though it is small.

In the future, only new scientific data will help us to better identify the risk of SCD in subjects with a Brugada type 1 ECG pattern, a possibly misleading ECG sign.

Manuscript source: Invited manuscript

Specialty type: Cardiac and cardiovascular systems

Country of origin: Italy

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B, B

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P- Reviewer: Iacoviello M, Letsas K S- Editor: Kong JX L- Editor: A E- Editor: Lu YJ

| 1. | Brugada P, Brugada J. Right bundle branch block, persistent ST-segment elevation and sudden cardiac death: a distinct clinical and electrocardiographic syndrome. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1992;20:1391-1396. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2298] [Cited by in RCA: 2126] [Article Influence: 64.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Priori SG, Blomström-Lundqvist C, Mazzanti A, Blom N, Borggrefe M, Camm J, Elliott PM, Fitzsimons D, Hatala R, Hindricks G. 2015 ESC Guidelines for the management of patients with ventricular arrhythmias and the prevention of sudden cardiac death: The Task Force for the Management of Patients with Ventricular Arrhythmias and the Prevention of Sudden Cardiac Death of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Endorsed by: Association for European Paediatric and Congenital Cardiology (AEPC). Eur Heart J. 2015;36:2793-2867. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2447] [Cited by in RCA: 2647] [Article Influence: 264.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Cabrera E, Sodi Pallares D. El gradient venrtriculr y la componente anormal en el diagnostico de los infartos del miocardio. Arch Inst Cardiol Mex. 1943;7:356. |

| 4. | Martini B, Nava A, Thiene G, Buja GF, Canciani B, Scognamiglio R, Daliento L, Dalla Volta S. Ventricular fibrillation without apparent heart disease: description of six cases. Am Heart J. 1989;118:1203-1209. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 249] [Cited by in RCA: 226] [Article Influence: 6.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Anselm DD, Evans JM, Baranchuk A. Brugada phenocopy: A new electrocardiogram phenomenon. World J Cardiol. 2014;6:81-86. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 59] [Cited by in RCA: 60] [Article Influence: 5.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 6. | Delise P, Allocca G, Sitta N, DiStefano P. Event rates and risk factors in patients with Brugada syndrome and no prior cardiac arrest: a cumulative analysis of the largest available studies distinguishing ICD-recorded fast ventricular arrhythmias and sudden death. Heart Rhythm. 2014;11:252-258. [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 7. | Brugada J, Brugada R, Brugada P. Determinants of sudden cardiac death in individuals with the electrocardiographic pattern of Brugada syndrome and no previous cardiac arrest. Circulation. 2003;108:3092-3096. [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 8. | Sacher F, Probst V, Iesaka Y, Jacon P, Laborderie J, Mizon-Gérard F, Mabo P, Reuter S, Lamaison D, Takahashi Y. Outcome after implantation of a cardioverter-defibrillator in patients with Brugada syndrome: a multicenter study. Circulation. 2006;114:2317-2324. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 237] [Cited by in RCA: 213] [Article Influence: 11.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Kamakura S, Ohe T, Nakazawa K, Aizawa Y, Shimizu A, Horie M, Ogawa S, Okumura K, Tsuchihashi K, Sugi K. Long-term prognosis of probands with Brugada-pattern ST-elevation in leads V1-V3. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol. 2009;2:495-503. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 225] [Cited by in RCA: 205] [Article Influence: 12.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Sarkozy A, Sorgente A, Boussy T, Casado R, Paparella G, Capulzini L, Chierchia GB, Yazaki Y, De Asmundis C, Coomans D. The value of a family history of sudden death in patients with diagnostic type I Brugada ECG pattern. Eur Heart J. 2011;32:2153-2160. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 70] [Cited by in RCA: 66] [Article Influence: 4.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Delise P, Allocca G, Marras E, Giustetto C, Gaita F, Sciarra L, Calo L, Proclemer A, Marziali M, Rebellato L. Risk stratification in individuals with the Brugada type 1 ECG pattern without previous cardiac arrest: usefulness of a combined clinical and electrophysiologic approach. Eur Heart J. 2011;32:169-176. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 151] [Cited by in RCA: 168] [Article Influence: 11.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Priori SG, Gasparini M, Napolitano C, Della Bella P, Ottonelli AG, Sassone B, Giordano U, Pappone C, Mascioli G, Rossetti G. Risk stratification in Brugada syndrome: results of the PRELUDE (PRogrammed ELectrical stimUlation preDictive valuE) registry. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2012;59:37-45. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 412] [Cited by in RCA: 444] [Article Influence: 34.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Eckardt L, Probst V, Smits JP, Bahr ES, Wolpert C, Schimpf R, Wichter T, Boisseau P, Heinecke A, Breithardt G. Long-term prognosis of individuals with right precordial ST-segment-elevation Brugada syndrome. Circulation. 2005;111:257-263. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 317] [Cited by in RCA: 283] [Article Influence: 14.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Takagi M, Yokoyama Y, Aonuma K, Aihara N, Hiraoka M; Japan Idiopathic Ventricular Fibrillation Study (J-IVFS) Investigators. Clinical characteristics and risk stratification in symptomatic and asymptomatic patients with brugada syndrome: multicenter study in Japan. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2007;18:1244-1251. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 103] [Cited by in RCA: 103] [Article Influence: 5.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Giustetto C, Drago S, Demarchi PG, Dalmasso P, Bianchi F, Masi AS, Carvalho P, Occhetta E, Rossetti G, Riccardi R, Bertona R, Gaita F; Italian Association of Arrhythmology and Cardiostimulation (AIAC)-Piedmont Section. Risk stratification of the patients with Brugada type electrocardiogram: a community-based prospective study. Europace. 2009;11:507-513. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 87] [Cited by in RCA: 87] [Article Influence: 5.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Probst V, Veltmann C, Eckardt L, Meregalli PG, Gaita F, Tan HL, Babuty D, Sacher F, Giustetto C, Schulze-Bahr E. Long-term prognosis of patients diagnosed with Brugada syndrome: Results from the FINGER Brugada Syndrome Registry. Circulation. 2010;121:635-643. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 595] [Cited by in RCA: 613] [Article Influence: 40.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Conte G, Sieira J, Ciconte G, de Asmundis C, Chierchia GB, Baltogiannis G, Di Giovanni G, La Meir M, Wellens F, Czapla J. Implantable cardioverter-defibrillator therapy in Brugada syndrome: a 20-year single-center experience. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2015;65:879-888. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 134] [Cited by in RCA: 152] [Article Influence: 15.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Antzelevitch C, Brugada P, Borggrefe M, Brugada J, Brugada R, Corrado D, Gussak I, LeMarec H, Nademanee K, Perez Riera AR. Brugada syndrome: report of the second consensus conference: endorsed by the Heart Rhythm Society and the European Heart Rhythm Association. Circulation. 2005;111:659-670. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1288] [Cited by in RCA: 1189] [Article Influence: 59.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Brugada P, Brugada R, Mont L, Rivero M, Geelen P, Brugada J. Natural history of Brugada syndrome: the prognostic value of programmed electrical stimulation of the heart. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2003;14:455-457. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 144] [Cited by in RCA: 133] [Article Influence: 6.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Sroubek J, Probst V, Mazzanti A, Delise P, Hevia JC, Ohkubo K, Zorzi A, Champagne J, Kostopoulou A, Yin X. Programmed Ventricular Stimulation for Risk Stratification in the Brugada Syndrome: A Pooled Analysis. Circulation. 2016;133:622-630. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 209] [Cited by in RCA: 187] [Article Influence: 20.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Mizusawa Y, Wilde AA. Brugada syndrome. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol. 2012;5:606-616. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 200] [Cited by in RCA: 207] [Article Influence: 15.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Ellenbogen KA, Levine JH, Berger RD, Daubert JP, Winters SL, Greenstein E, Shalaby A, Schaechter A, Subacius H, Kadish A; Defibrillators in Non-Ischemic Cardiomyopathy Treatment Evaluation (DEFINITE) Investigators. Are implantable cardioverter defibrillator shocks a surrogate for sudden cardiac death in patients with nonischemic cardiomyopathy? Circulation. 2006;113:776-782. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 251] [Cited by in RCA: 246] [Article Influence: 12.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Sacher F, Probst V, Maury P, Babuty D, Mansourati J, Komatsu Y, Marquie C, Rosa A, Diallo A, Cassagneau R. Outcome after implantation of a cardioverter-defibrillator in patients with Brugada syndrome: a multicenter study-part 2. Circulation. 2013;128:1739-1747. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 175] [Cited by in RCA: 176] [Article Influence: 14.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Delise P, Allocca G, Sitta N. Risk of sudden death in subjects with Brugada type 1 electrocardiographic pattern and no previous cardiac arrest: is it high enough to justify an extensive use of prophylactic ICD? J Cardiovasc Med (Hagerstown). 2016;17:408-410. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Okamura H, Kamakura T, Morita H, Tokioka K, Nakajima I, Wada M, Ishibashi K, Miyamoto K, Noda T, Aiba T. Risk stratification in patients with Brugada syndrome without previous cardiac arrest – prognostic value of combined risk factors. Circ J. 2015;79:310-317. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 49] [Cited by in RCA: 53] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Sieira J, Conte G, Ciconte G, Chierchia GB, Casado-Arroyo R, Baltogiannis G, Di Giovanni G, Saitoh Y, Juliá J, Mugnai G. A score model to predict risk of events in patients with Brugada Syndrome. Eur Heart J. 2017;38:1756-1763. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Nademanee K, Veerakul G, Chandanamattha P, Chaothawee L, Ariyachaipanich A, Jirasirirojanakorn K, Likittanasombat K, Bhuripanyo K, Ngarmukos T. Prevention of ventricular fibrillation episodes in Brugada syndrome by catheter ablation over the anterior right ventricular outflow tract epicardium. Circulation. 2011;123:1270-1279. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Brugada J, Pappone C, Berruezo A, Vicedomini G, Manguso F, Ciconte G, Giannelli L, Santinelli V. Brugada Syndrome Phenotype Elimination by Epicardial Substrate Ablation. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol. 2015;8:1373-1381. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 205] [Cited by in RCA: 176] [Article Influence: 17.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |