Peer-review started: May 9, 2016

First decision: June 13, 2016

Revised: July 23, 2016

Accepted: September 21, 2016

Article in press: September 22, 2016

Published online: January 26, 2017

Processing time: 257 Days and 15.2 Hours

In patients with history of coronary artery disease angina pectoris is usually attributed to the progression of atherosclerotic lesions. However, in patients with previous coronary artery bypass graft operation (CABG) using internal mammary artery grafts, great vessel disease should also be considered. Herein we present two patients with history of CABG whose symptoms were suspicious for coronary ischemia. During cardiac catheterization reverse blood flow was observed from the left artery disease to the left internal mammary artery (LIMA) graft in both cases. After angioplasty and stent implantation of the left subclavian artery antegrade flow was restored in the LIMA grafts and both patients had complete resolution of symptoms.

Core tip: Both coronary and peripheral artery diseases are comorbidities with increasing morbidity and mortality. In patients with history of coronary artery disease and previous coronary revascularization, angina pectoris is usually attributed to the progression of atherosclerotic lesions. However, in patients who previously underwent coronary artery bypass graft operation (CABG) using internal mammary artery grafts, subclavian artery disease should also be considered. Herein we present 2 patients who previously underwent CABG with symptoms of myocardial ischemia due to subclavian artery stenosis.

- Citation: Heid J, Vogel B, Kristen A, Kloos W, Kohler B, Katus HA, Korosoglou G. Interventional treatment of the left subclavian in 2 patients with coronary steal syndrome. World J Cardiol 2017; 9(1): 65-70

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1949-8462/full/v9/i1/65.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4330/wjc.v9.i1.65

Coronary and peripheral artery disease (CAD and PAD) are both comorbidities which exhibit a high prevalence and increasing morbidity and mortality in the western world[1]. Especially PAD is estimated to affect over 200 million people worldwide, and around 30% of primary care individuals over 70 years old[2,3]. Patients with symptomatic PAD exhibit a life expectancy of 80% at 5 years of follow-up, whereas 20% of such patients experience non-fatal cardiovascular complications[4,5]. Interestingly, PAD patients have significantly less chance of receiving appropriate risk factor modification (e.g., statin therapy) and antithrombotic treatment compared to patients with CAD[1]. In addition, the prevalence of unrecognised PAD is extremely high (68%) in patients referred for coronary angiography for suspected CAD, especially in individuals with low socioeconomic status[6].

In patients with history of CAD and previous coronary revascularization, angina pectoris is usually attributed to the progression of atherosclerotic lesions. However, in patients who previously underwent coronary artery bypass graft operation (CABG) using internal mammary artery grafts, great vessel disease, for example of the subclavian artery, should also be considered. In this regard, the coronary subclavian steal syndrome is a rare complication after CABG when the left internal mammary artery (LIMA) graft is used. This disease is characterized by retrograde flow from the LIMA graft to the distal post-stenotic part of the subclavian artery during muscle work and increased oxygen and blood demand of the arm in order to maintain adequate perfusion of the left hand. As a result, patients with such a condition may develop typical symptoms of myocardial ischemia despite patency of the grafted vessels.

Herein we present a mini series of two patients (Patient A, Patient B) with suspected progress of the known multi-vessel CAD. Both patients had history of previous CABG including a LIMA graft to the left artery disease (LAD). Baseline characteristics of our patients are provided in Table 1.

| Patient A | Patient B | |

| Sex | Male | Male |

| Age (yr) | 75 | 78 |

| Cardiovascular risk factors | Arterial hypertension Hyperlipidemia Obesity | Arterial hypertension Hyperlipidemia Previous smoker |

| CAD | Known 3-vessel-disease | Known 2-vessel disease |

| CABG | 14 yr ago LIMA graft to the LAD Venous grafts to the right coronary (RCA) and the LCX | 9 yr ago LIMA graft to the LAD Venous graft to the first marginal branch |

| Left ventricular function | Mildly impaired | Mildly impaired |

| PAD history | Previous recanalization of left (2009) and right (2010) superficial femoral artery | Surgical endatherectomy of the left internal carotid artery 2013 High grade lesions in the left vertebral artery and left subclavian artery (accidental finding in a computed tomography performed one year earlier) |

| Initial symptoms | Typical angina symptoms (CCS III) | Presyncope and atypical angina |

| Baseline medication | Aspirin ß-blocker Angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitor Statin | Aspirin ß-blocker Angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitor Statin Calcium antagonist Diuretics |

Patient A was referred to our department for an elective coronary angiography due to typical angina symptoms (CCS class III) during exertion since 4 wk. He had a history of multi vessel disease with prior CABG 14 years ago.

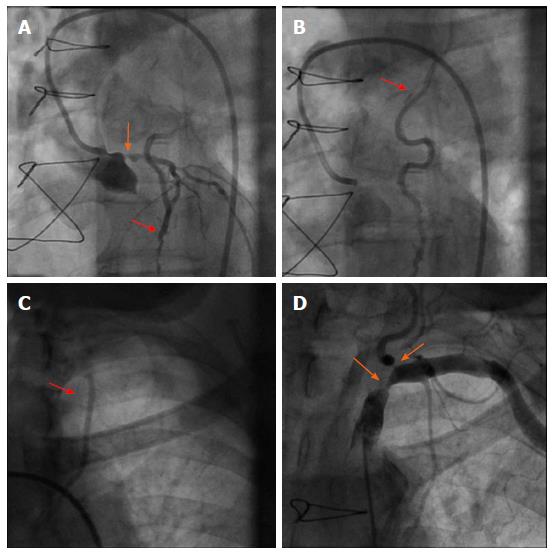

The initial coronary angiography revealed a 75% ostial stenosis of the left main coronary artery. Despite the presence of significant left main stenosis, reverse blood flow was observed from the LAD to the LIMA graft. Thus, contrast opacification could be followed up to the insertion of the graft at the subclavian artery (Figure 1). Both the 2 vein grafts to the left circumflex and the right coronary artery were patent. In addition, angiography of the subclavian artery revealed high grade lesions in the subclavian and the origin of the left vertebral artery (Figure 1). Hereby, con-current retrograde flow from the LAD was observed during contrast agent injection.

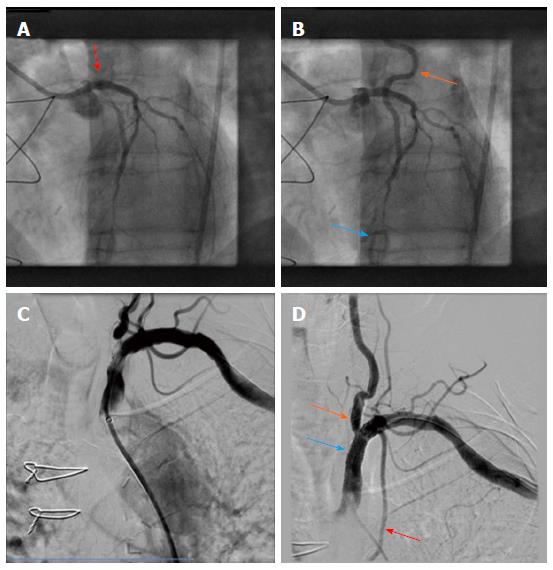

Due to typical angina and significant left main disease, PCI of left main artery and stent placement (Promus Element 4.0 mm × 20 mm, Boston Scientific) was performed in patient A with a good angiographic result (Figure 2). However, retrograde flow from the LAD to the LIMA graft remained after percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI), and sparse flow was seen in the distal LAD despite successful left main PCI (orange and blue arrows in Figure 2, respectively). After 4 wk the patient was scheduled for PCI of his left subclavian artery due to suspected LIMA steal syndrome. Interestingly, at that time he reported on persistence of CCS class III anginal symptoms. Angioplasty could be performed successfully, followed by bifurcation stent implantation of the stenotic subclavian and vertebral arteries (balloon expandable Visi-Pro 8.0 mm × 27 mm, Covidien for the subclavian and Taxus Element 4.5 mm × 12 mm, Boston Scientific for the vertebral artery) and final kissing balloon inflation. Subsequently, a good angiographic result was observed with restored antegrade flow indicated in the LIMA graft (Figure 2).

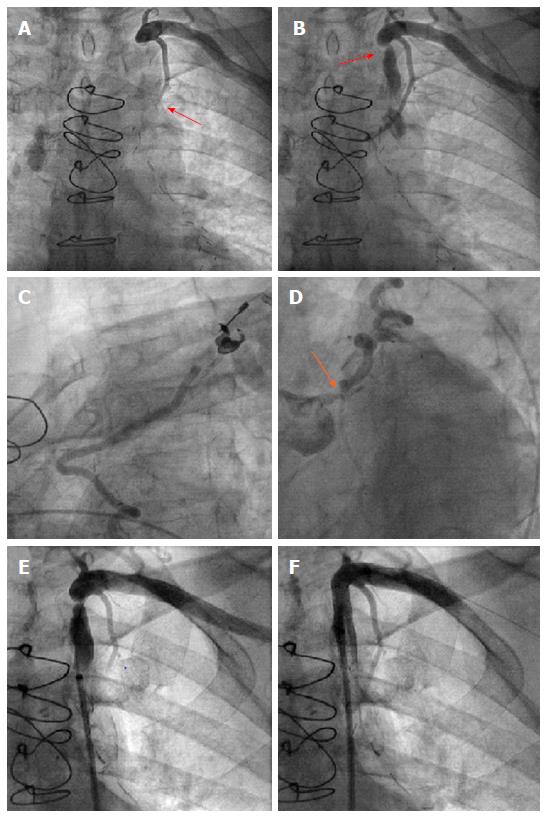

For patient B, the initial cause for admission to our hospital was a presyncopal episode and atypical angina. Cardiac catheterization was performed due to the high risk profile of the patient, including known multi-vessel disease and CABG 9 years ago. After selection of a left radial access for coronary angiography and wire insertion into the subclavian artery, we proceeded with selective contrast injection into the LIMA graft to the LAD. Surprisingly, contrast opacification was not possible despite selective contrast injection into the presumably patent vessel (Figure 3). Subsequently, angiography of the left subclavian artery was performed, confirming high grade stenosis of the left subclavian artery (Figure 3), which was already accidentally diagnosed one year earlier during a computed tomography scan. Consistently an interarm blood pressure difference of 20 mmHg (left < right) could be measured with this patient. The subclavian stenosis was located proximally to the origin of the LIMA graft, thus possibly causing a coronary steal syndrome. Coronary angiography confirmed this diagnosis demonstrating retrograde flow from the LAD up to the insertion of the LIMA graft into the subclavian artery (Figure 3) despite the presence of significant left main disease (Figure 3). On the following day, stress echocardiography was performed, demonstrating an inducible hypokinesia in the anterior LV-wall by arm exertion (“hand grip method”), compatible with inducible ischemia in the LAD territory. Subsequently, balloon angioplasty and stent placement of the left subclavian artery was performed using an Armada 6.0 mm × 20 mm balloon and an 8.0 mm × 27 mm VisiPro-Stent with good angiographic result (Figure 3). Importantly, antegrade flow could be reestablished in the subclavian artery after interventional treatment (Figure 3).

Both patients were discharged the day after the procedure. During clinical follow-up patient A showed complete resolution auf his angina symptoms, whereas repeated stress echocardiography showed no signs of inducible ischemia in patient B.

Subclavian artery stenosis is a relatively frequent disease, which is more commonly described in patients with diabetes mellitus and was shown to be predictive of poor cardiovascular outcomes[7]. Known PAD accompanied by a interarm blood pressure difference greater than 10% has been suggested as a specific, but unfortunately less sensitive indicator for a subclavian stenosis[8]. The presence of subclavian artery stenosis in patients with previous CABG, who have received a LIMA graft can lead to angina symptoms independent of atherosclerosis progression in native coronary arteries and bypass grafts. Although several cases of subclavian artery causing a so-called LIMA steal syndrome have been reported in the literature, this syndrome is still considered as relatively uncommon in patients after myocardial revascularization. However, in light of the greater number of LIMA grafts currently used and their long life expectancy its incidence may be higher than expected. In a retrospective study including 226 patients scheduled for CABG, 6 (3%) patients had significant left subclavian artery stenosis, which was successfully treated by angioplasty and stent placement in all cases before bypass surgery[9]. In our case the presence of subclavian artery stenosis was not investigated prior to CABG in our 2 cases. However, due to the long time duration between CABG and angina symptoms of the patient (A: 14 years, B: 9 years) it is more likely that subclavian stenosis developed after CABG. Thus, pre-CABG angiography would probably not have been helpful in our cases.

In the past years, significant technical developments have occurred with endovascular therapy, which offer several distinct advantages over open surgical revascularization techniques in selected lesions[10]. Although no head-to-head trials comparing interventional vs surgical treatment of the proximal subclavian artery stenosis are present so far, the effectiveness of percutaneous revascularization seems to be at least equivalent to surgery and that PCI and stent placement may be associated with fewer procedure-related serious complications[11]. In our patients subclavian (in both patients) and vertrebral artery stenosis (in patient B) could be successfully treated by balloon angioplasty and stent placement. This caused restoration of the antegrade flow into the LIMA graft, resulting in resolution of anginal symptoms with patient A and restoration of the inducible wall motion abnormality by echocardiography in patient B. In patient A treatment of the subclavian artery stenosis may have been enough to restore antegrade perfusion of the LAD territory via the anatomically patent LIMA graft, without requiring PCI of the left main. However, PCI of the left main had already been performed in the initial session during diagnostic coronary angiography. Due to the fact that symptoms remained, we decided to perform stenting of the subclavian artery stenosis in a second session.

In patients with previous myocardial revascularization apart from CAD, great vessel disease resulting to coronary steal syndromes needs to be considered as a rare but important alternative diagnosis. In such cases, interventional treatment by angioplasty and stent placement may lead to complete resolution of symptoms and possible prevention of ischemic complications.

A 75- and 78-year-old male patient, both with known coronary artery disease, peripheral artery disease and prior coronary artery bypass graft who presented with symptoms of myocardial ischemia.

Peripheral artery disease with subclavian artery stenosis causing coronary steal syndrome.

Progression of coronary artery disease.

All labs were within normal limits.

Peripheral artery disease was diagnosed in both patients by digital subtraction angiography.

Coronary steal syndrome due to subclavian artery disease.

Percutaneous balloon angioplasty and stent placement in the left subclavian artery.

Coronary steal syndrome is a pathologic entity, which has been previously reported quite rarely so far in the current literature. This disease can sometimes be confused with coronary artery disease due to typical symptoms of myocardial ischemia in such patients.

Coronary steal syndrome is a relatively rare condition, where subclavian artery stenosis causes myocardial ischemia due to reduced blood flow to the left internal mammary artery coronary graft after coronary artery bypass graft operation.

In patients with previous myocardial revascularization apart from coronary artery disease, great vessel disease resulting to coronary steal syndromes needs to be considered as a rare but important alternative diagnosis.

The authors present 2 rare case reports of coronary subclavian steal syndrome after coronary artery bypass graft. The authors have demonstrated that interventional treatment may lead to complete resolution of symptoms and possible prevention of ischemic complications. This manuscript is nicely structured and well written.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Cardiac and cardiovascular systems

Country of origin: Germany

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): A

Grade B (Very good): B, B

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P- Reviewer: Peteiro J, Sabate M, Ueda H S- Editor: Qiu S L- Editor: A E- Editor: Wu HL

| 1. | Gallino A, Aboyans V, Diehm C, Cosentino F, Stricker H, Falk E, Schouten O, Lekakis J, Amann-Vesti B, Siclari F. Non-coronary atherosclerosis. Eur Heart J. 2014;35:1112-1119. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 91] [Cited by in RCA: 120] [Article Influence: 10.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Fowkes FG, Rudan D, Rudan I, Aboyans V, Denenberg JO, McDermott MM, Norman PE, Sampson UK, Williams LJ, Mensah GA. Comparison of global estimates of prevalence and risk factors for peripheral artery disease in 2000 and 2010: a systematic review and analysis. Lancet. 2013;382:1329-1340. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2122] [Cited by in RCA: 2439] [Article Influence: 203.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Hirsch AT, Criqui MH, Treat-Jacobson D, Regensteiner JG, Creager MA, Olin JW, Krook SH, Hunninghake DB, Comerota AJ, Walsh ME. Peripheral arterial disease detection, awareness, and treatment in primary care. JAMA. 2001;286:1317-1324. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1957] [Cited by in RCA: 1858] [Article Influence: 77.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Norgren L, Hiatt WR, Dormandy JA, Nehler MR, Harris KA, Fowkes FG. Inter-Society Consensus for the Management of Peripheral Arterial Disease (TASC II). J Vasc Surg. 2007;45 Suppl S:S5-67. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4051] [Cited by in RCA: 4110] [Article Influence: 228.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Rothwell PM, Coull AJ, Silver LE, Fairhead JF, Giles MF, Lovelock CE, Redgrave JN, Bull LM, Welch SJ, Cuthbertson FC. Population-based study of event-rate, incidence, case fatality, and mortality for all acute vascular events in all arterial territories (Oxford Vascular Study). Lancet. 2005;366:1773-1783. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 745] [Cited by in RCA: 668] [Article Influence: 33.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Chang P, Nead KT, Olin JW, Cooke JP, Leeper NJ. Clinical and socioeconomic factors associated with unrecognized peripheral artery disease. Vasc Med. 2014;19:289-296. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Aboyans V, Criqui MH, McDermott MM, Allison MA, Denenberg JO, Shadman R, Fronek A. The vital prognosis of subclavian stenosis. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2007;49:1540-1545. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 94] [Cited by in RCA: 99] [Article Influence: 5.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Osborn LA, Vernon SM, Reynolds B, Timm TC, Allen K. Screening for subclavian artery stenosis in patients who are candidates for coronary bypass surgery. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2002;56:162-165. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 69] [Cited by in RCA: 65] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Prasad A, Prasad A, Varghese I, Roesle M, Banerjee S, Brilakis ES. Prevalence and treatment of proximal left subclavian artery stenosis in patients referred for coronary artery bypass surgery. Int J Cardiol. 2009;133:109-111. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | White CJ, Gray WA. Endovascular therapies for peripheral arterial disease: an evidence-based review. Circulation. 2007;116:2203-2215. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 108] [Cited by in RCA: 92] [Article Influence: 5.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Eisenhauer AC. Subclavian and Innominate Revascularization: Surgical Therapy Versus Catheter-Based Intervention. Curr Interv Cardiol Rep. 2000;2:101-110. [PubMed] |