Published online Aug 26, 2016. doi: 10.4330/wjc.v8.i8.456

Peer-review started: April 6, 2016

First decision: May 17, 2016

Revised: June 7, 2016

Accepted: July 11, 2016

Article in press: July 13, 2016

Published online: August 26, 2016

Processing time: 142 Days and 7.7 Hours

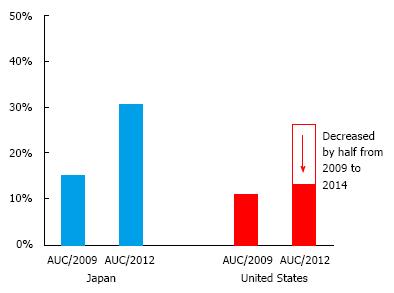

The aim of this review was to summarize the concept of appropriate use criteria (AUC) regarding percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) and document AUC use and impact on clinical practice in Japan, in comparison with its application in the United States. AUC were originally developed to subjectively evaluate the indications and performance of various diagnostic and therapeutic modalities, including revascularization techniques. Over the years, application of AUC has significantly impacted patient selection for PCI in the United States, particularly in non-acute settings. After the broad implementation of AUC in 2009, the rate of inappropriate PCI decreased by half by 2014. The effect was further accentuated by incorporation of financial incentives (e.g., restriction of reimbursement for inappropriate procedures). On the other hand, when the United States-derived AUC were applied to Japanese patients undergoing elective PCI from 2008 to 2013, about one-third were classified as inappropriate, largely due to the perception gap between American and Japanese experts. For example, PCI for low-risk non-left atrial ascending artery lesion was more likely to be classified as appropriate by Japanese standards, and anatomical imaging with coronary computed tomography angiography was used relatively frequently in Japan, but no scenario within the current AUC includes this modality. To extrapolate the current AUC to Japan or any other region outside of the United States, these local discrepancies must be taken into consideration, and scenarios should be revised to reflect contemporary practice. Understanding the concept of AUC as well as its perception gap between different counties will result in the broader implementation of AUC, and lead to the quality improvement of patients’ care in the field of coronary intervention.

Core tip: The concept of appropriate use criteria (AUC) regarding percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) has significantly impacted patient selection for PCI in the United States, particularly in non-acute settings. In Japan, when the United States-derived AUC were applied to Japanese patients, about one-third of elective cases were classified as inappropriate. This is largely due to the perception gap between American and Japanese experts. To extrapolate the current AUC to Japan or any other regions outside of the United States, these local discrepancies must be taken into consideration, and scenarios should be revised to reflect contemporary practice.

- Citation: Inohara T, Kohsaka S, Ueda I, Yagi T, Numasawa Y, Suzuki M, Maekawa Y, Fukuda K. Application of appropriate use criteria for percutaneous coronary intervention in Japan. World J Cardiol 2016; 8(8): 456-463

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1949-8462/full/v8/i8/456.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4330/wjc.v8.i8.456

To improve the quality of care, such as indications for and performance of various procedures, appropriate use criteria (AUC) have been developed. The concept of AUC has been widely accepted to aid in quantifying and improving the quality of care, and AUC have become available in various diagnostic and therapeutic modalities[1-3]. In the field of coronary intervention, the potential overutilization of percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) has come under harsh criticism, particularly after the initial report of the Clinical Outcomes Utilizing Revascularization and Aggressive Drug Evaluation (COURAGE) trial[4]. In this setting, AUC for coronary revascularization were developed in 2009 and revised in 2012 in the United States[5,6].

In this review, we aimed to provide an overview of the concept of AUC for coronary revascularization and its impact on the selection of patients undergoing PCI in the United States. Furthermore, we sought to clarify the appropriate ratings of PCI indications in Japan based on the current United States-derived AUC. Finally, we discuss issues that remain to be resolved when extrapolating the current AUC to Japanese clinical practice and propose the future direction of this concept in Japanese cardiovascular society. This minireview will aid in the broader implementation of the concept of AUC in various countries outside of the United States, and will lead to improve the quality of care, especially patients’ selection, in PCI.

PCI providing emergent or urgent recanalization of acute thrombi has played a crucial role in treating patients with acute coronary syndrome (ACS). The so-called “open artery hypothesis” proposes that early reperfusion through infarcted coronary arteries leads to better clinical outcomes than nonreperfusion. Reopening an occluded coronary artery would minimize myocardial injury, preserves cardiac function, and may ultimately improve overall survival.

From the same scientific rationale for improving patient longevity, preventing future acute coronary syndrome, and relieving anginal symptoms, PCI was also widely implemented in table ischemic heart disease (SIHD) patients for a fairly short time period. However, in the past decade, increasing scientific evidence has highlighted the unclear benefit of PCI on SIHD, and expectations for PCI have been tempered[7]. This issue was further underscored by the publication of the COURAGE trial[8], a multicenter study that recruited most of its patients from the Veterans Administration Hospital Network and failed to demonstrate clear benefits of PCI for hard endpoints (mortality and/or myocardial infarction) in comparison with optimized medical therapy alone in patients with SIHD. Concern towards overuse of PCI has emerged, and the above neutral results for PCI in the non-acute setting provoked a debate in the reconsideration of the indications for elective PCI.

Under these circumstances, 6 professional societies in the United States [American College of Cardiology Foundation (ACCF)/Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions (SCAI)/Society of Thoracic Surgeons (STS)/American Association for Thoracic Surgery (AATS)/American Heart Association (AHA)/American Society of Nuclear Cardiology (ASNC)] have presented their own “appropriate use” provisions in order to solve this problem. The original criteria were developed in 2009, and the revised version was published in 2012[5,6].

The process of evaluating appropriateness was based on the RAND approach, which blends scientific evidence, guidelines, and practical experience by engaging a technical panel in a modified Delphi exercise. In brief, nationally recognized experts were recruited, and the panel included interventional cardiologists, cardiovascular surgeons, and general cardiologists. Over 200 clinical scenarios were prepared. Initially, the members independently rated the appropriateness of performing PCI in these clinical scenarios using a 9-point scale, with 1 point regarded as being the most inappropriate and 9 points as being the most appropriate, based on different combinations of the following items: (1) Anatomical information [left main trunk (LMT), 3-vessel disease (VD), 1- or 2-VD with/without proximal left anterior descending artery (LAD) involvement]; (2) Evaluation of the presence and severity of preoperative ischemia (treadmill, exercise myocardial scintigraphy, and stress echocardiography); (3) Presence and severity of symptoms [asymptomatic, Canadian Cardiovascular Society (CCS) scale 1-4]; and (4) Presence of optimal medical therapy. An example would be as follows.

Asymptomatic patient with diabetes; after screening electrocardiography performed at an annual health check-up revealed abnormalities, coronary computed tomography angiography (CCTA) findings indicated severe stenosis in the mid-right coronary artery; myocardial scintigraphy revealed mild ischemia in the relevant area, which was consistent with the finding of CCTA; drugs administered: Aspirin (100 mg), rosuvastatin (2.5 mg).

When this scenario is evaluated using the 4 evaluation points for AUC, the patient would be classified as having “asymptomatic single-vessel disease without proximal LAD involvement and mild ischemia, and no optimal medical therapy”. According to the AUC, each evaluation committee member determines the appropriateness of PCI based on such a simplified scenario. The panel then met for a face-to-face discussion, and the panel members independently re-provided their final scores for each indication. Each panel member had equal weight in producing the final result. The median score was documented for each scenario. Based on the median score for each indication (range, 1-9), they were categorized as “appropriate” (median, 7-9), “uncertain” (4-6), or “inappropriate” (1-3).

A set of AUC was initially proposed to review clinical decisions made by medical teams in each facility. In addition, after its publication and initial phase of implementation, attempts have been made to assess the appropriateness of the indications for PCI in actual clinical practice by applying these AUC to large-scale registry data[9,10]. The results of the analysis of PCI appropriateness in the United States revealed that in acute settings, the procedure was generally adapted appropriately. By contrast, in non-acute settings, 11.6% of PCIs were deemed to be inappropriate (by 2009 AUC), and when using the revised 2012 AUC, as many as 26.2% of PCIs were evaluated as inappropriate, indicating the overuse of PCI for SIHD (Figure 1).

At the same time, the following changes were observed from 2009 to 2014[10], which were thought to popularize the concept of AUC: (1) The rates of patients with serious symptoms (CCS 3 or 4), patients with severe ischemia, and patients receiving optimal medical therapy increased; (2) The annual trend revealed that the rate of inappropriate PCI decreased from 26.2% to 13.3% (Figure 1), and the ratio of elective PCI patients decreased 30% overall; and (3) The variance of appropriateness among facilities also improved.

In the United States, on the basis of a study by Hachamovitch et al[11] demonstrating that PCI-related prognostic improvement could only be obtained in cases with > 10% ischemic area, pre-procedural evaluation of the extent of ischemia is deemed almost essential. Furthermore, reflecting the COURAGE trial, clinical guidelines also emphasize the use of optimal medical therapy prior to revascularization. From such evidence, PCI in cases of 1- or 2-VD without proximal LAD involvement and optimal medical therapy is not accepted regardless of patient symptoms. Additionally, coronary artery bypass graft (CABG) is considered to be a more appropriate therapeutic strategy than PCI for multivessel CAD, based on the findings of the Synergy between PCI with Taxus and Cardiac Surgery (SYNTAX) trial[12] and the Future Revascularization Evaluation in Patients with Diabetes Mellitus: Optimal Management of Multivessel Disease (FREEDOM) trial[13].

Consequently, according to the CathPCI registry (National Cardiovascular Data Registry), there was a significant 33.8% reduction in the volume of non-acute PCI procedures from 2010 (89704) to 2014 (59375)[10]. Similarly, analysis of the Clinical Outcomes Assessment Program also demonstrated a 43% decline in the number of PCIs for elective indications (from 3818 in 2010 to 2193 in 2013)[14].

The number of PCI procedures has continued to increase in Japan. More than 250000 procedures in > 800 hospitals were performed in 2014, which is estimated to be > 14 times greater than the number of CABG procedures. The proportion of elective procedure accounts for < 40% of all PCI in the United States, and as many as three-fourths of PCIs are performed in non-acute settings in Japan[15,16].

To document the rate of appropriate vs. inappropriate PCI in Japanese practice, we applied US AUC scenario ratings to patients registered in the Japan Cardiovascular Database - Keio interhospital Cardiovascular Studies (JCD-KiCS). JCD-KiCS is an ongoing prospective multicenter registry built to collect clinical background and outcome data on consecutive PCI patients in 15 centers affiliated with Keio University Hospital (11258 patients registered from 2008 to 2013)[17-22].

Similar to the results in the United States, PCI was generally performed appropriately in acute settings. However, in non-acute settings, 15% of PCI cases were classified as inappropriate under the 2009 AUC, and 30.7% of PCI cases were categorized as inappropriate under the revised 2012 AUC. As mentioned earlier, when the 2009 AUC was applied, the rate of inappropriate PCI in the United States was 11%, and when the revised 2012 AUC was used, the rate ranged from 13% to 26%; based on these findings, the rate of inappropriate PCI in Japan is high (Figure 1).

This higher rate of inappropriate PCIs in Japan compared with the United States is mostly driven by differences in the therapeutic strategy toward patients with low-risk ischemia. In contrast to the United States practice, where indications for PCI are strictly limited to cases with > 10% ischemia, PCI for low-risk patients is considered acceptable in Japan. The Japanese Stable Angina Pectoris (JSAP) trial evaluated the effectiveness of PCI for such stable low-risk CAD patients compared with medical therapy in Japan, and the results were strikingly different from those of the COURAGE trial. In the JSAP trial, the long-term benefit of PCI compared to conservative management was observed[23]. The JSAP trial enrolled 384 patients with low-risk CAD consisting of 1- or 2-VD from 78 institutions in Japan. This trial was conducted in a randomized fashion, and patients were randomly allocated to a medical therapy only group or PCI plus medical therapy group. The primary end point was the composite of all-cause death, ACS admission, cerebrovascular accidents, and emergency hospitalization. During the 3.3-year follow-up, the incidence of the primary composite end point was significantly lower in the PCI plus medical therapy group compared to the initial medical therapy-only group, which demonstrated the effectiveness of PCI for stable CAD patients at low-risk for cardiovascular events.

However, the JSAP trial had several concerns. First, the benefit of PCI was only recognized in the composite end point and disappeared for all-cause death. This discrepancy could obscure the prognostic impact of PCI for this low-risk population. Furthermore, in this trial, the medical therapy was not optimal in either group. The prescription rates of statin and beta-blocker were 45.2% and 51.6%, respectively, even in the medical therapy group. From the insight of the COURAGE trial[8], implementation of the optimal medical therapy was an equivalent therapeutic option for the management of low-risk CAD patients, and the findings of the JSAP trial should be cautiously interpreted.

We have also previously evaluated the appropriateness of PCI, based on both the United States and Japanese AUC, and compared the ratings[18]. Japanese AUC was developed in the line with the United States AUC; however, several issues have merged since the establishment of J-AUC. J-AUC was published in 2007, and this was before the publication of COURAGE trial. Therefore, the importance of optimal medical therapy was not highlighted in the clinical practice guidelines then. Furthermore, the J-AUC panel was weighted more toward coronary interventionists (7, in comparison to 2 cardiac surgeons). Thorough revision is needed for the application of J-AUC, but it reflected consensus toward the indication of PCI in Japan to some extent. Naturally, the rate of inappropriate PCI under J-AUC in JCD-KiCS was substantially lower (5.2%) than that using the US AUC (15%); the rating discrepancies between the US- and J-AUC were largely due to difference in the interpretation of revascularization in asymptomatic, low- or intermediate-risk patients without proximal LAD involvement. This discrepancy may be related to multiple factors including cultural differences and the unique Japanese healthcare system. It also underscores the need for revision of AUC according to their associated culture and healthcare system.

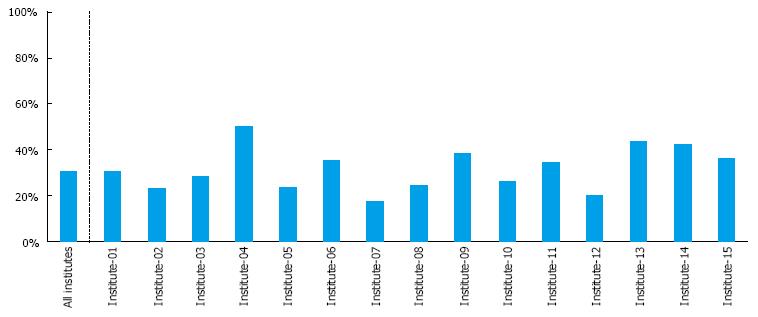

Lastly, the variability of the appropriate ratings among institutes is also an issue that remains to be resolved. When the current United States AUC was applied to our registered dataset (JCD-KiCS registry), the rate of inappropriate PCI varied across institutes, ranging from 17.5% to 50% (Figure 2). This finding suggests uneven care in the field of coronary intervention in Japan, which should be resolved to improve the quality of care. Hospital-level variation in the proportion of PCIs classified as inappropriate was also found in the United States. However, since the launch of the AUC in 2009, it has substantially improved[10]. The concept of AUC has tremendous potential to improve patient selection for PCI, and is expected to gain wider acceptance in Japanese clinical practice.

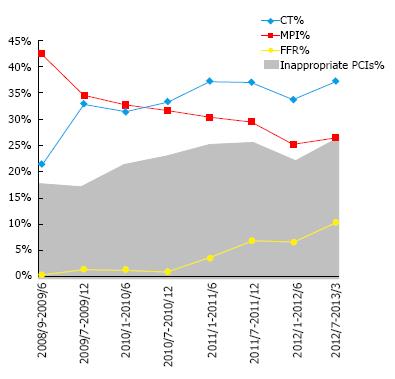

Can the current United States-derived AUC be directly applied to daily clinical practice in Japan? There are several problems concerning this issue. First, the modalities for evaluating CAD differ between the United States and Japan. In the United States, stress testing, including treadmill, myocardial scintigraphy, and stress echocardiography, is generally used to assess ischemia. However, in recent years, CCTA has become widespread in Japan, and fractional flow reserve (FFR) is often used to assess ischemia. Since appropriateness criteria assign high value to functional information, reflecting a strong tilt toward physiological assessment of ischemia in the United States, CCTA, which only provides anatomical information, is not recognized as one of the prior non-invasive tests under these criteria. We previously indicated that due to the popularity of CCTA and FFR, Japanese PCI cannot be adequately evaluated under the current AUC developed in the United States (Figure 3)[17], and an editorial published from the American perspective entitled “lessons learned from Japan” also mentions this problem[24].

Second, as quoted previously, the therapeutic strategy toward patients with low-risk ischemia differs greatly between the United States and Japan. Clearly, further studies involving the Japanese population are needed to close the perception gap for PCI indications that lack sufficient scientific underpinning.

Finally, there is room for improvement in the current AUC proposed in the United States. For example, clinical scenarios involving PCI for chronic total occlusion (CTO) are limited to “chronic total occlusion of 1 major epicardial coronary artery, without other coronary stenosis”; therefore other types of CTO-PCI cannot be accurately evaluated[5,6,19]. In addition, although the use of FFR is limited to cases with moderate stenosis, it should be widely accepted in evaluating various lesions. Based on the results of the FFR vs angiography for multi-vessel evaluation II (FAME2) study[25], the prevalence of FFR-guided PCI substantially increased[17,26]. Because FFR enables the evaluation of the significance of CAD in the cardiac catheterization laboratory, pre-procedural tests might have been omitted in some patients; therefore, patients evaluated only by FFR are likely to be classified as having inappropriate PCI, unless such cases are properly assigned to FFR-related scenarios. However, in the current AUC, ischemic evaluation by FFR is accepted only for 1- or 2-vessel CAD with borderline stenosis of “50% to 60%”, and the use of FFR in coronary artery stenosis greater than 60% was not adjudicated[5,6].

Previously, we discussed such issues concerning the current AUC with United States investigators in the form of correspondence to the paper by Inohara et al[27] and Brandley et al[14,28]. We mainly insisted on the validity of performing CCTA as a pre-procedural evaluation. However, although they agreed that AUC comprise a living document and require frequent revision to incorporate evolving evidence, they disagreed with our opinion, since pre-procedural evaluation using CCTA was performed in only 0.5% of all PCIs registered in their dataset. When considering such perception gaps, it is impractical to extrapolate the current AUC advocated in the United States to daily clinical practice in Japan. In order to popularize the concept of appropriate ratings in Japan, further effort is needed to refine and correct the disconnection between the current AUC and Japanese clinical practice.

Although the revision of the current AUC in accordance with the daily clinical practice in Japan will require some effort, the effects that the concept of AUC brings are expected to be extremely large. As previously discussed, the application of AUC in the United States led to a reduction in the number of elective PCI by half.

A recent study by Chinese investigators demonstrated that the medical records of many patients undergoing PCI lacked documentation of important process measures needed to assess quality of care[29]. AUC can serve as a foundation to guide future efforts on quality improvement in the use of PCI in such cases. Variation in quality of care across hospitals has also been noted in European countries. In a hospital-level international comparison of patients with acute myocardial infarction admitted to hospitals in Sweden and the United Kingdom, inter-hospital variation in the use of primary PCI, antiplatelet treatment, and statin at discharge were important in explaining variation in 30-d mortality[30]. The results of this study suggest that more consistent adherence to new treatment guidelines across all hospitals would deliver improved outcomes, and standardizing the appropriateness of the revascularization procedures could aid in facilitating this adherence.

In Japan, the Japanese Association of Cardiovascular Intervention and Therapeutics (CVIT) has developed a nationwide registry designed to collect clinical variables and outcome data on PCI patients (J-PCI), which is also linked to medical specialty boards. Therefore, it is feasible that the construction of a feedback system via such a registry will lead to the popularization and practical use of AUC in daily clinical practice in Japan. However, issues concerning the balance between the professionalism and autonomy of physicians are deeply involved, making it difficult to reach a conclusion regarding the role of physician discretion in the decision to perform PCI. Looking at various past examples in Japan, the Japanese public appears to have developed a negative attitude toward organizations, including specialized professional groups that have failed to perform self-auditing. For this reason, we believe that some sort of restriction toward the indication of PCIs such as AUC will be implemented in the near future.

The concept of AUC has shown great value as a quality measure and led to improved patient selection for PCI in the United States. Although several issues remain to be resolved in order to extrapolate the current AUC to Japanese clinical practice, this concept should be introduced to improve the quality of care in Japan and other countries.

The authors appreciate the contributions of all the investigators and clinical coordinators involved in the JCD-KiCS registry.

Manuscript source: Invited manuscript

Specialty type: Cardiac and cardiovascular systems

Country of origin: Japan

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): A

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P- Reviewer: Celik T, Xiao DL S- Editor: Ji FF L- Editor: A E- Editor: Lu YJ

| 1. | Brindis RG, Douglas PS, Hendel RC, Peterson ED, Wolk MJ, Allen JM, Patel MR, Raskin IE, Hendel RC, Bateman TM. ACCF/ASNC appropriateness criteria for single-photon emission computed tomography myocardial perfusion imaging (SPECT MPI): a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation Quality Strategic Directions Committee Appropriateness Criteria Working Group and the American Society of Nuclear Cardiology endorsed by the American Heart Association. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2005;46:1587-1605. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 266] [Cited by in RCA: 235] [Article Influence: 12.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Hendel RC, Patel MR, Kramer CM, Poon M, Hendel RC, Carr JC, Gerstad NA, Gillam LD, Hodgson JM, Kim RJ. ACCF/ACR/SCCT/SCMR/ASNC/NASCI/SCAI/SIR 2006 appropriateness criteria for cardiac computed tomography and cardiac magnetic resonance imaging: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation Quality Strategic Directions Committee Appropriateness Criteria Working Group, American College of Radiology, Society of Cardiovascular Computed Tomography, Society for Cardiovascular Magnetic Resonance, American Society of Nuclear Cardiology, North American Society for Cardiac Imaging, Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions, and Society of Interventional Radiology. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2006;48:1475-1497. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1092] [Cited by in RCA: 948] [Article Influence: 49.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Douglas PS, Khandheria B, Stainback RF, Weissman NJ, Brindis RG, Patel MR, Khandheria B, Alpert JS, Fitzgerald D, Heidenreich P. ACCF/ASE/ACEP/ASNC/SCAI/SCCT/SCMR 2007 appropriateness criteria for transthoracic and transesophageal echocardiography: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation Quality Strategic Directions Committee Appropriateness Criteria Working Group, American Society of Echocardiography, American College of Emergency Physicians, American Society of Nuclear Cardiology, Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions, Society of Cardiovascular Computed Tomography, and the Society for Cardiovascular Magnetic Resonance endorsed by the American College of Chest Physicians and the Society of Critical Care Medicine. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2007;50:187-204. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 258] [Cited by in RCA: 227] [Article Influence: 12.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Borden WB, Redberg RF, Mushlin AI, Dai D, Kaltenbach LA, Spertus JA. Patterns and intensity of medical therapy in patients undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention. JAMA. 2011;305:1882-1889. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 127] [Cited by in RCA: 117] [Article Influence: 8.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Patel MR, Dehmer GJ, Hirshfeld JW, Smith PK, Spertus JA. ACCF/SCAI/STS/AATS/AHA/ASNC 2009 Appropriateness Criteria for Coronary Revascularization: a report by the American College of Cardiology Foundation Appropriateness Criteria Task Force, Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions, Society of Thoracic Surgeons, American Association for Thoracic Surgery, American Heart Association, and the American Society of Nuclear Cardiology Endorsed by the American Society of Echocardiography, the Heart Failure Society of America, and the Society of Cardiovascular Computed Tomography. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009;53:530-553. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 399] [Cited by in RCA: 419] [Article Influence: 26.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Patel MR, Dehmer GJ, Hirshfeld JW, Smith PK, Spertus JA. ACCF/SCAI/STS/AATS/AHA/ASNC/HFSA/SCCT 2012 Appropriate use criteria for coronary revascularization focused update: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation Appropriate Use Criteria Task Force, Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions, Society of Thoracic Surgeons, American Association for Thoracic Surgery, American Heart Association, American Society of Nuclear Cardiology, and the Society of Cardiovascular Computed Tomography. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2012;59:857-881. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 355] [Cited by in RCA: 392] [Article Influence: 30.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Bangalore S, Maron DJ, Hochman JS. Evidence-Based Management of Stable Ischemic Heart Disease: Challenges and Confusion. JAMA. 2015;314:1917-1918. [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 8. | Boden WE, O’Rourke RA, Teo KK, Hartigan PM, Maron DJ, Kostuk WJ, Knudtson M, Dada M, Casperson P, Harris CL. Optimal medical therapy with or without PCI for stable coronary disease. N Engl J Med. 2007;356:1503-1516. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3259] [Cited by in RCA: 3208] [Article Influence: 178.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Chan PS, Patel MR, Klein LW, Krone RJ, Dehmer GJ, Kennedy K, Nallamothu BK, Weaver WD, Masoudi FA, Rumsfeld JS. Appropriateness of percutaneous coronary intervention. JAMA. 2011;306:53-61. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 133] [Cited by in RCA: 142] [Article Influence: 10.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Desai NR, Bradley SM, Parzynski CS, Nallamothu BK, Chan PS, Spertus JA, Patel MR, Ader J, Soufer A, Krumholz HM. Appropriate Use Criteria for Coronary Revascularization and Trends in Utilization, Patient Selection, and Appropriateness of Percutaneous Coronary Intervention. JAMA. 2015;314:2045-2053. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 198] [Cited by in RCA: 189] [Article Influence: 18.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Hachamovitch R, Hayes SW, Friedman JD, Cohen I, Berman DS. Comparison of the short-term survival benefit associated with revascularization compared with medical therapy in patients with no prior coronary artery disease undergoing stress myocardial perfusion single photon emission computed tomography. Circulation. 2003;107:2900-2907. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1163] [Cited by in RCA: 1113] [Article Influence: 50.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Serruys PW, Morice MC, Kappetein AP, Colombo A, Holmes DR, Mack MJ, Ståhle E, Feldman TE, van den Brand M, Bass EJ. Percutaneous coronary intervention versus coronary-artery bypass grafting for severe coronary artery disease. N Engl J Med. 2009;360:961-972. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2982] [Cited by in RCA: 2993] [Article Influence: 187.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Farkouh ME, Domanski M, Sleeper LA, Siami FS, Dangas G, Mack M, Yang M, Cohen DJ, Rosenberg Y, Solomon SD. Strategies for multivessel revascularization in patients with diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2012;367:2375-2384. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1325] [Cited by in RCA: 1344] [Article Influence: 103.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Bradley SM, Bohn CM, Malenka DJ, Graham MM, Bryson CL, McCabe JM, Curtis JP, Lambert-Kerzner A, Maynard C. Temporal Trends in Percutaneous Coronary Intervention Appropriateness: Insights From the Clinical Outcomes Assessment Program. Circulation. 2015;132:20-26. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 50] [Cited by in RCA: 57] [Article Influence: 5.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | The Japanese Circulation Society. Jcs national survey on management of cardiovascular diseases: Annual report. Available from: http://www.j-circ.or.jp/jittai_chosa/jittai_chosa2014web.pdf. |

| 16. | Dehmer GJ, Weaver D, Roe MT, Milford-Beland S, Fitzgerald S, Hermann A, Messenger J, Moussa I, Garratt K, Rumsfeld J. A contemporary view of diagnostic cardiac catheterization and percutaneous coronary intervention in the United States: a report from the CathPCI Registry of the National Cardiovascular Data Registry, 2010 through June 2011. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2012;60:2017-2031. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 222] [Cited by in RCA: 228] [Article Influence: 17.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Inohara T, Kohsaka S, Miyata H, Ueda I, Ishikawa S, Ohki T, Nishi Y, Hayashida K, Maekawa Y, Kawamura A. Appropriateness ratings of percutaneous coronary intervention in Japan and its association with the trend of noninvasive testing. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2014;7:1000-1009. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 37] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Inohara T, Kohsaka S, Miyata H, Ueda I, Noma S, Suzuki M, Negishi K, Endo A, Nishi Y, Hayashida K. Appropriateness of coronary interventions in Japan by the US and Japanese standards. Am Heart J. 2014;168:854-861.e11. [PubMed] |

| 19. | Inohara T, Kohsaka S, Miyata H, Ueda I, Hayashida K, Maekawa Y, Kawamura A, Numasawa Y, Suzuki M, Noma S. Real-World Use and Appropriateness of Coronary Interventions for Chronic Total Occlusion (from a Japanese Multicenter Registry). Am J Cardiol. 2015;116:858-864. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Inohara T, Kohsaka S, Abe T, Miyata H, Numasawa Y, Ueda I, Nishi Y, Naito K, Shibata M, Hayashida K. Development and validation of a pre-percutaneous coronary intervention risk model of contrast-induced acute kidney injury with an integer scoring system. Am J Cardiol. 2015;115:1636-1642. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Inohara T, Miyata H, Ueda I, Maekawa Y, Fukuda K, Kohsaka S. Use of Intra-aortic Balloon Pump in a Japanese Multicenter Percutaneous Coronary Intervention Registry. JAMA Intern Med. 2015;175:1980-1982. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Kohsaka S, Miyata H, Ueda I, Masoudi FA, Peterson ED, Maekawa Y, Kawamura A, Fukuda K, Roe MT, Rumsfeld JS. An international comparison of patients undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention: A collaborative study of the National Cardiovascular Data Registry (NCDR) and Japan Cardiovascular Database-Keio interhospital Cardiovascular Studies (JCD-KiCS). Am Heart J. 2015;170:1077-1085. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 49] [Cited by in RCA: 65] [Article Influence: 6.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Nishigaki K, Yamazaki T, Kitabatake A, Yamaguchi T, Kanmatsuse K, Kodama I, Takekoshi N, Tomoike H, Hori M, Matsuzaki M. Percutaneous coronary intervention plus medical therapy reduces the incidence of acute coronary syndrome more effectively than initial medical therapy only among patients with low-risk coronary artery disease a randomized, comparative, multicenter study. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2008;1:469-479. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 70] [Cited by in RCA: 70] [Article Influence: 4.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Hung OY, Samady H, Anderson HV. Appropriate use criteria: lessons from Japan. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2014;7:1010-1013. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | De Bruyne B, Pijls NH, Kalesan B, Barbato E, Tonino PA, Piroth Z, Jagic N, Möbius-Winkler S, Rioufol G, Witt N. Fractional flow reserve-guided PCI versus medical therapy in stable coronary disease. N Engl J Med. 2012;367:991-1001. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1837] [Cited by in RCA: 1992] [Article Influence: 153.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Pothineni NV, Shah NS, Rochlani Y, Nairooz R, Raina S, Leesar MA, Uretsky BF, Hakeem A. U.S. Trends in Inpatient Utilization of Fractional Flow Reserve and Percutaneous Coronary Intervention. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2016;67:732-733. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 43] [Cited by in RCA: 51] [Article Influence: 5.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Inohara T, Kohsaka S, Fukuda K. Letter by Inohara et al Regarding Article, “Temporal Trends in Percutaneous Coronary Intervention Appropriateness: Insights From the Clinical Outcomes Assessment Program”. Circulation. 2016;133:e423. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Bradley SM, Bohn CM, Malenka DJ, Graham MM, Bryson CL, McCabe JM, Curtis JP, Lambert-Kerzner A, Maynard C. Response to Letter Regarding Article, “Temporal Trends in Percutaneous Coronary Intervention Appropriateness: Insights From the Clinical Outcomes Assessment Program”. Circulation. 2016;133:e424. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Zheng X, Curtis JP, Hu S, Wang Y, Yang Y, Masoudi FA, Spertus JA, Li X, Li J, Dharmarajan K. Coronary Catheterization and Percutaneous Coronary Intervention in China: 10-Year Results From the China PEACE-Retrospective CathPCI Study. JAMA Intern Med. 2016;176:512-521. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 57] [Cited by in RCA: 71] [Article Influence: 7.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Chung SC, Sundström J, Gale CP, James S, Deanfield J, Wallentin L, Timmis A, Jernberg T, Hemingway H. Comparison of hospital variation in acute myocardial infarction care and outcome between Sweden and United Kingdom: population based cohort study using nationwide clinical registries. BMJ. 2015;351:h3913. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 85] [Cited by in RCA: 85] [Article Influence: 8.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |