Published online Jun 26, 2016. doi: 10.4330/wjc.v8.i6.379

Peer-review started: January 14, 2016

First decision: February 29, 2016

Revised: March 22, 2016

Accepted: May 7, 2016

Article in press: May 9, 2016

Published online: June 26, 2016

Processing time: 163 Days and 0.4 Hours

Extracorporeal life support (ECLS) has recently been reported to have a survival benefit in patients with cardiac arrest. It is now used widely as a lifesaving modality. Here, we describe a case of sudden cardiac arrest (SCA) in a young athlete with an anomalous origin of the right coronary artery from the left coronary sinus. Resuscitation was successful using ECLS before curative bypass surgery. We highlight the efficacy of ECLS for a patient with SCA caused by a rare, unexpected aetiology. In conclusion, ECLS was a lifesaving modality for SCA due to an anomalous coronary artery in this young patient.

Core tip: We describe the case of an adolescent with out-of-hospital cardiac arrest during intense physical activity; this patient had an anomalous origin of the right coronary artery from the left coronary sinus. He was resuscitated successfully using extracorporeal life support (ECLS). This case highlights the utility of ECLS for a young patient with refractory sudden cardiac arrest due to this rare, unexpected aetiology.

- Citation: Park JW, Lee JH, Kim KS, Bang DW, Hyon MS, Lee MH, Park BW. Successful extracorporeal life support in sudden cardiac arrest due to coronary anomaly. World J Cardiol 2016; 8(6): 379-382

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1949-8462/full/v8/i6/379.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4330/wjc.v8.i6.379

Coronary artery anomalies are rare, but they may be fatal and can cause sudden cardiac arrest (SCA). In such cases, the most common cause of cardiac arrest is functional stenosis of the anomalous artery between the pulsatile great vessels, especially in young athletes during or after intense physical activity[1].

It was recently reported that extracorporeal life support (ECLS) confers a survival benefit in patients with prolonged cardiac arrest when conventional cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) fails[2]. We herein describe the case of an adolescent with out-of-hospital cardiac arrest during intense physical activity; this patient had an anomalous origin of the right coronary artery (RCA) from the left coronary sinus confirmed by cardiac computed tomography (CT) and coronary angiography. He was resuscitated successfully using ECLS. This case highlights the utility of ECLS for a young patient with refractory SCA due to this rare, unexpected aetiology.

A 17-year-old male patient was brought to the emergency room (ER) for urgent treatment of SCA that had occurred while playing basketball. His medical history was non-contributory. There was no family history of sudden cardiac death, collagen vascular disease, or congenital heart disease. In the ambulance, defibrillation was performed four times for ventricular fibrillation, and CPR was continued for about 25 min before arrival at the ER.

On arrival, the patient was in a coma, and his vital signs could not be checked. CPR was continued for an additional 30 min in the ER. However, this was not successful, and refractory cardiac arrest with ventricular fibrillation continued. To restore the systemic circulation and adequate organ perfusion, ECLS was planned with a veno-arterial approach using the femoral artery and vein. After starting ECLS, the ventricular fibrillation subsided spontaneously without further cardiac arrest. The vital signs stabilised (blood pressure via a left radial artery line, 112/54 mmHg; pulse rate, 94/min; respiratory rate, 16/min; body temperature, 33 °C). The low body temperature was due to hypothermia therapy.

An initial electrocardiogram after ECLS implementation showed atrial fibrillation with ST depression in leads II, III, and aVF, indicating myocardial ischaemia. Echocardiography showed severe left ventricle (LV) systolic dysfunction (ejection fraction, 30%) with global hypokinesia, a dilated LV (LV diastolic dimension, 54 mm), and mild pulmonary hypertension (estimated pulmonary artery pressure, 32 mmHg; inferior vena cava size, 14.7 mm). On laboratory testing, the levels of troponin T (0.291 ng/mL; normal, < 0.1 ng/mL) and creatine kinase-MB (8.74 ng/mL; normal, < 6 ng/mL) were elevated, and blood gas analysis showed metabolic acidosis. A chest X-ray showed interstitial pulmonary oedema. One hour after starting ECLS, the oxygen pressure (PaO2) via the left radial artery was 81.7 mmHg, and the oxygen saturation (SaO2) was 91.8%. Forty-eight hours later, his vital signs remained stable and he was alert with no neurological deficit. The pulmonary oedema resolved.

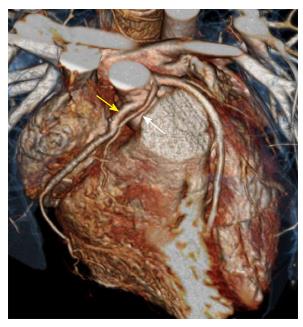

The electrocardiogram showed normal sinus rhythm. Follow-up echocardiography 24 h later showed improved LV function (ejection fraction, 42%) without LV ballooning (LV diastolic dimension, 47 mm) or pulmonary hypertension (estimated pulmonary artery pressure, 26 mmHg). The mean central venous pressure via the left subclavian vein was 6 mmHg, and the pulse pressure via the left radial artery was maintained during ECLS. On the second day, ECLS was removed successfully with normalised LV function (ejection fraction, 63%). Cardiac CT and coronary angiography were performed to evaluate the aetiology of the SCA. CT and coronary angiography showed that the RCA originated from the left coronary sinus and ran between the aorta and pulmonary trunk, causing severe functional stenosis of the proximal segment of the RCA (Figure 1). Nine days after SCA, neo-ostium formation of the RCA with a saphenous vein graft was conducted without complications (Figure 2), and the patient was discharged on day 33. One and a half years later, he was well with no neurological deficits or complications.

An estimated 350000 deaths occur annually due to SCA in the United States. Despite advances in emergency care, only 3% to 10% of patients with SCA survive after successful resuscitation[3]. However, new techniques such as ECLS and hypothermia therapy have improved the outcome of SCA. ECLS can serve as bridging therapy for the recovery of cardiac and respiratory function, replacing heart function while minimising myocardial work and improving organ perfusion. ECLS has a survival rate 36% higher than that expected from traditional CPR[4]. Because our patient had SCA with refractory ventricular fibrillation despite optimal resuscitation, ECLS was initiated as soon as possible to allow for the recovery of cardiac function.

SCA is uncommon in people with no history of cardiac problems. In the young, congenital coronary anomalies remain an important cause of SCA, especially during or after extreme exercise. Therefore, we must evaluate the possibility of coronary artery anomalies systemically in all such cases[5]. There are no advance warnings of impending SCA in 55% to 93% of patients with coronary anomalies[6].

SCA due to an anomalous coronary artery is presumed to occur with the collapse of the anomalous coronary artery along its route between the great vessels with pulmonary hypertension occurring after extreme exercise. Collapse of the coronary artery results acute myocardial ischaemia over a wide territory, which causes SCA. With ECLS, the right ventricle load is decreased and pulmonary hypertension is improved, which obviates the requirement for catecholamines and improves the perfusion of other organs[7]. However, ECLS has some disadvantages. First, severe cardiac dysfunction, excessive ECLS support, or inadequate preload can increase the afterload and induce pulmonary trunk expansion, which leads to functional stenosis of the anomalous coronary artery[8]. In our case, although the pulmonary arterial pressure was not monitored by Swan–Ganz catheterisation, the central venous pressure and maximum pressure of tricuspid regurgitation by echocardiography were not elevated during ECLS, which reflects improved pulmonary arterial hypertension. Maintained pulsatility via the left radial artery and improved LV systolic function without LV ballooning might exclude inadequate LV decompression by ECLS. Second, ECLS may result in a zone of deoxygenated blood in the aortic root and hypoxic blood perfusion in the coronary arteries[9]. In our case, the oxygen saturation via the left radial artery was maintained at > 90%, which excluded coronary hypoperfusion after ECLS.

To our knowledge, this is the first report of successful resuscitation by immediate implantation of ECLS in a young patient with SCA due to a coronary anomaly. ECLS can be considered a lifesaving modality for SCA due to anomalous coronary arteries in the young.

ECLS is a viable alternative to CPR and should be considered early and instituted rapidly in cases of SCA in institutions where it is available. Congenital coronary anomalies remain an important cause of SCA in the young and should be evaluated systematically in all such cases.

A 17-year-old man with no significant medical history presented with a sudden cardiac arrest (SCA) which was occurred by coronary anomaly: Right coronary artery (RCA) from left coronary sinus.

When the patient was arrived, his pulse was asystole, with coma mental status.

Because of the patient was young adult, we have to be differential diagnosis include coronary artery anomalies of wrong sinus origin, hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, myocarditis, arrhythmia include Brugada syndrome, and ion channelopathies.

Cardiac marker include troponin T and creatine kinase-MB were elevated, and blood gas analysis showed metabolic acidosis.

Coronary computed tomography and coronary angiography shows coronary anomaly; RCA from left coronary sinus running between aorta and pulmonary trunk causing functional stenosis of proximal segment.

Extracorporeal life supporting (ECLS) was applied to maintain the patient’s cardiac function, after that neo-ostium formation of the RCA with a saphenous vein graft was conducted.

SCA due to an anomalous coronary artery is uncommon in people with no history of cardiac problems, and survivor rate is poor. ECLS can serve as bridging therapy for the recovery of cardiac and respiratory function, replacing heart function while minimising myocardial work and improving organ perfusion.

ECLS is a viable alternative to cardiopulmonary resuscitation and should be considered early and instituted rapidly in cases of SCA in institutions where it is available. Congenital coronary anomalies remain an important cause of SCA in the young and should be evaluated systematically in all such cases.

The authors reported the case of a patient with anomalous origin of RCA, successful saved from cardiac arrest. There are other cases in literature, that described the use of ECLS as support in cardiac arrest and this case further attest the utility of this support. We congratulate the authors for this well described case.

P- Reviewer: Bonanno C, Sung K S- Editor: Kong JX L- Editor: A E- Editor: Jiao XK

| 1. | Frescura C, Basso C, Thiene G, Corrado D, Pennelli T, Angelini A, Daliento L. Anomalous origin of coronary arteries and risk of sudden death: a study based on an autopsy population of congenital heart disease. Hum Pathol. 1998;29:689-695. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 368] [Cited by in RCA: 351] [Article Influence: 13.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Ishaq M, Pessotto R. Might rapid implementation of cardiopulmonary bypass in patients who are failing to recover after a cardiac arrest potentially save lives? Interact Cardiovasc Thorac Surg. 2013;17:725-730. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Haïssaguerre M, Derval N, Sacher F, Jesel L, Deisenhofer I, de Roy L, Pasquié JL, Nogami A, Babuty D, Yli-Mayry S. Sudden cardiac arrest associated with early repolarization. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:2016-2023. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1100] [Cited by in RCA: 986] [Article Influence: 58.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Younger JG, Schreiner RJ, Swaniker F, Hirschl RB, Chapman RA, Bartlett RH. Extracorporeal resuscitation of cardiac arrest. Acad Emerg Med. 1999;6:700-707. [PubMed] |

| 5. | Hillis LD, Cohn PF. Nonatherosclerotic coronary artery disease. Diagnosis and therapy of coronary artery disease. Springer. 1985;495-505. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 6. | Angelini P, Velasco JA, Flamm S. Coronary anomalies: incidence, pathophysiology, and clinical relevance. Circulation. 2002;105:2449-2454. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 602] [Cited by in RCA: 579] [Article Influence: 25.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 7. | Hoeper MM, Granton J. Intensive care unit management of patients with severe pulmonary hypertension and right heart failure. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2011;184:1114-1124. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 191] [Cited by in RCA: 190] [Article Influence: 14.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Chung M, Shiloh AL, Carlese A. Monitoring of the adult patient on venoarterial extracorporeal membrane oxygenation. ScientificWorldJournal. 2014;2014:393258. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 53] [Cited by in RCA: 74] [Article Influence: 6.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Sidebotham D, McGeorge A, McGuinness S, Edwards M, Willcox T, Beca J. Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation for treating severe cardiac and respiratory failure in adults: part 2-technical considerations. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth. 2010;24:164-172. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 119] [Cited by in RCA: 115] [Article Influence: 7.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |