Published online Feb 26, 2016. doi: 10.4330/wjc.v8.i2.220

Peer-review started: July 4, 2015

First decision: Septermber 17, 2015

Revised: October 4, 2015

Accepted: November 23, 2015

Article in press: November 25, 2015

Published online: February 26, 2016

Processing time: 237 Days and 11.3 Hours

AIM: To determine the impact of red blood cell distribution width on outcome in anemic patients undergoing transcatheter aortic valve implantation (TAVI).

METHODS: In a retrospective single center cohort study we determined the impact of baseline red cell distribution width (RDW) and anemia on outcome in 376 patients with aortic stenosis undergoing TAVI. All patients were discussed in the institutional heart team and declined for surgical aortic valve replacement due to high operative risk. Collected data included patient characteristics, imaging findings, periprocedural in hospital data, laboratory results and follow up data. Blood samples for hematology and biochemistry analysis were taken from every patient before and at fixed intervals up to 72 h after TAVI including blood count and creatinine. Descriptive statistics were used for patient’s characteristics. Kaplan-Meier survival curves were used for time to event outcomes. A recursive partitioning regression and classification was used to investigate the association between potential risk factors and outcome variables.

RESULTS: Mean age in our study population was 81 ± 6.1 years. Anemia was prevalent in 63.6% (n = 239) of our patients. Age and creatinine were identified as risk factors for anemia. In our study population, anemia per se did influence 30-d mortality but did not predict longterm mortality. In contrast, a RDW > 14% showed to be highly predictable for a reduced short- and longterm survival in patients with aortic valve disease after TAVI procedure.

CONCLUSION: Age and kidney function determine the degree of anemia. The anisocytosis of red blood cells in anemic patients supplements prognostic information in addition to that derived from the WHO-based definition of anemia.

Core tip: This is a retrospective study to evaluate the impact of prevalent anemia and the importance of red cell distribution width (RDW) on the outcome in patients undergoing transcatheter aortic valve replacement. Anemia was prevalent 63.6% of the patients and did influence 30-d mortality but did not predict longterm mortality. In contrast, a RDW > 14% showed to be highly predictable for a reduced short- and long-term survival in patients with aortic valve disease after transcatheter aortic valve implantation procedure. Age and creatinine were identified as risk factors for anemia.

- Citation: Hellhammer K, Zeus T, Verde PE, Veulemanns V, Kahlstadt L, Wolff G, Erkens R, Westenfeld R, Navarese EP, Merx MW, Rassaf T, Kelm M. Red cell distribution width in anemic patients undergoing transcatheter aortic valve implantation. World J Cardiol 2016; 8(2): 220-230

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1949-8462/full/v8/i2/220.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4330/wjc.v8.i2.220

Anemia is common in elderly patients with cardiovascular disease. An association of increased mortality with decreasing levels of hemoglobin has been shown in patients with coronary artery disease (CAD), acute myocardial infarction, cardiac heart failure (CHF) and structural heart disease[1-4]. Anemia also affects outcome after percutaneous coronary artery intervention (PCI), coronary artery bypass graft (CABG), and transcatheter aortic valve replacement (TAVI)[5-7]. In patients with aortic valve disease anemia often occurs in combination with occult bleeding within the gastro-intestinal tract.

According to the WHO, anemia is defined by a level of hemoglobin < 13 g/dL in men and < 12 g/dL in women[8]. Studies correcting anemia by either erythropoiesis stimulating agents (ESA) or by transfusion of packed red blood cells (RBC) yielded conflicting results[9]. ESA failed to improve outcome in acute myocardial infarction[10], chronic kidney disease[11], and heart failure[12]. RBC transfusions to patients undergoing primary PCI[13,14], CABG[15], and TAVI[7], respectively, may be even harmful and were associated with increased mortality. The storage lesion and subsequent scavenging of nitric oxide (NO) through occult hemolysis after transfusion may at least in part account for these detrimental effects[15-17]. These data raise the question whether or not the mere determination of the hemoglobin levels is appropriate for risk stratification and guidance of anemia treatment in mostly elderly patients at high cardiovascular risk.

Red blood cell distribution width (RDW) is a quantitative measure of anisocytosis, the variability in size of circulating RBC. It is routinely measured in automated hematology analyzers and is reported together with hemoglobin, RBC number, and hematocrit as a component of complete blood count. RDW is typically elevated in conditions of ineffective RBC production, e.g., iron or vitamin B12 deficiency, increased RBC destruction such as in hemolysis, after blood transfusion or during severe inflammation. Conceivably, RDW may represent an integrative measure of multiple pathologic processes in the elderly patient with structural heart disease, explaining its strong association with clinical short and long term outcomes[18-24]. Relevant comorbidities affecting RDW in those patients may include renal dysfunction, inflammatory stress, and nutritional deficiencies. Thus, the measurement of RDW as compared to hemoglobin may add or provide even superior information to stratification of those high risk patients with advanced aortic valve stenosis undergoing TAVI procedures.

Recent studies indicate that the detrimental effects of anemia is not only mediated by the absolute hemoglobin levels, but also by the quality of the endogenous and the substituted RBCs. Different subtypes of anemia affect the outcome after stenting in stable coronary artery disease distinctly[25]. Red cell distribution width (RDW) has emerged as a novel marker not only of the size of erythrocytes, but also as an index of quality and function of RBC[19,26]. RDW is a powerful and independent predictor of mortality in cardiac heart failure[18,20,21]. The role of RDW in anemic patients undergoing TAVI is not clear. We therefore investigated whether RDW may have the potential to act as a novel prognostic parameter for risk stratification in addition to anemia, as defined by WHO criteria.

The study population consisted of 376 patients with severe symptomatic aortic stenosis who underwent TAVI with either the Medtronic CoreValve system (Medtronic Inc, Minneapolis, MN) or the Edwards SAPIEN Valve (Edwards Lifesciences, Irvine, CA) from August 2009 to August 2013 at the Heart Center Duesseldorf. All patients were discussed in the institutional heart team and declined for surgical aortic valve replacement due to high operative risk. All patients gave their written informed consent for TAVI and the use of clinical, procedural and follow up data for research. Study procedures were in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and the institutional Ethics Committee of the Heinrich-Heine University approved the study protocol. The study is registered at clinical trials (NCT01805739).

Collected data included patient characteristics, imaging findings, periprocedural in hospital data, laboratory results and follow up data. Blood samples for hematology and biochemistry analysis were taken from every patient before and at fixed intervals up to 72 h after TAVI including blood count and creatinine. As reported by the World Health Organisation (WHO) baseline anemia was defined as a hemoglobin (Hb) level of < 13 g/dL for men and < 12 g/dL for women. Preoperative serum creatinine values were used to calculate the baseline serum creatinine clearance using the Cockcroft and Gault equation[27]. Chronic kidney disease (CKD) was defined as a calculated serum clearance < 60 mL/min[28]. Clinical endpoints were reported according to The Valve Academic Research Consortium (VARC) consensus statement[29]. Follow up data for mortality were collected by contacting the attending physician and the civil registries. Technical appendix, statistical code, and dataset are available from the corresponding author. Participants gave informed consent for data sharing.

TAVI procedures were performed according to current guidelines[30]. A single antibiotic shot was given shortly before TAVI procedure. All patients were referred to intensive care after the procedure. For antiplatelet therapy, patients received a combination therapy of aspirin 100 mg/d and clopidogrel 75 mg/d for three months after TAVI followed by permanent aspirin mono therapy. Patients on oral anticoagulation received clopidogrel 75 mg/d and oral anticoagulation for three months followed by oral anticoagulation.

The statistical methods of this study were reviewed by Pablo E Verde from the Coordination Center for Clinical Trials Düsseldorf. Descriptive statistics are based on frequency tables for categorical data, means and standard deviations for continuous variables and Kaplan-Meier survival curves for time to event outcomes. Association between continues variables are analyzed with Person’s correlation coefficient and displayed graphically with scatter plots.

A recursive partitioning regression and classification was used to investigate the association between potential risk factors and outcome variables. This approach is based on the method describe by Horhorn et al[31]. This technique combines an algorithm for recursive partitioning together with a well defined theory of permutation tests. Multiple test procedures are applied to determine whether a significant association between any of the covariables and the response variable can be stated. The resulting partitioning regression analysis is graphically displayed as a classification tree. The partitioning nodes are displayed by an optimal cut-off point for continues covariables and with a classification split for categorical covariables. Each node-split is assessed with a P-value calculated by a permutation test. In addition, regression analysis for binary outcomes was performed using the classical logistic regression and for time to event outcomes the proportional hazard Cox’s regression. In each case we report results for all covariables included in the model and with covariables selected by using a step-wise variable selection based on taking the minimum value of AIC (Akaike Information Criteria). As graphical outputs for regression analysis a forest plot is used, in this figure the odds ratio and the 95% confidence interval is displayed for each variable in the model. Data analysis was performed using the statistical software R version 3.1.0[32], SPSS Statistics 22 (IBM®) and GraphPad (Prism®).

Anemia was prevalent in 63.6% (n = 239) of our study population (Table 1). Groups with and without anemia did not differ except for chronic kidney disease (P = 0.001), history of myocardial infarction (P = 0.029), and the need for dialysis due to end-stage chronic kidney disease (P = 0.009).

| Entire cohort (n = 376) | Anemia (n = 239) | No anemia (n = 137) | P-value | |

| Age, years ± SD | 81 ± 6.1 | 82 ± 6.2 | 81 ± 5.9 | 0.101 |

| Male | 167 (44.4) | 112 (46.9) | 55 (40.1) | 0.207 |

| Weight, kg ± SD | 74 ± 14.4 | 73 ± 14.2 | 75 ± 15.0 | 0.351 |

| Height, cm ± SD | 168 ± 8.8 | 168 ± 8.7 | 168 ± 9.1 | 0.685 |

| NYHA III and IV | 288 (76.6) | 187 (78.6) | 101 (73.7) | 0.284 |

| CAD | 263 (69.9) | 170 (71.1) | 93 (67.9) | 0.209 |

| Previous myocardial infarction | 39 (10.4) | 31 (13.0) | 8 (5.8) | 0.029 |

| Previous percutaneous intervention | 168 (44.7) | 113 (47.3) | 55 (40.1) | 0.181 |

| Previous CABG | 89 (23.7) | 55 (23.1) | 34 (24.8) | 0.708 |

| Previous valve | 8 (2.1) | 5 (2.1) | 3 (2.2) | 0.954 |

| Previous stroke | 34 (9.0) | 23 (9.6) | 11 (8.0) | 0.604 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 93 (24.7) | 59 (24.7) | 34 (28.4) | 0.977 |

| Hypertension | 355 (94.4) | 224 (93.7) | 131 (95.6) | 0.441 |

| Peripheral vascular disease | 115 (30.6) | 75 (31.4) | 40 (29.2) | 0.658 |

| Cerebroarterial vascular disease | 81 (21.5) | 56 (23.4) | 25 (18.2) | 0.239 |

| COPD | 72 (19.1) | 46 (19.2) | 26 (19.0) | 0.949 |

| Atrial fibrillation | 87 (23.1) | 52 (21.8) | 35 (25.5) | 0.414 |

| Permanent pacemaker | 64 (17.0) | 43 (18.1) | 21 (15.3) | 0.497 |

| Chronic kidney disease | 203 (54.0) | 144 (60.3) | 59 (43.1) | 0.001 |

| Dialysis | 21 (5.6) | 19 (7.9) | 2 (1.5) | 0.009 |

| Aortic valve area, cm²± SD | 0.73 ± 0.2 | 0.71 ± 0.19 | 0.75 ± 0.22 | 0.094 |

| Mitral regurgitation ≥ grade II | 114 (30.3) | 73 (32.2) | 41 (31.5) | 0.904 |

| LVEF < 30% | 20 (5.3) | 16 (6.7) | 4 (2.9) | 0.253 |

| LVEF 30%-44% | 68 (18.1) | 47 (19.7) | 21 (15.3) | 0.292 |

| LVEF 45%-55% | 49 (13.0) | 29 (12.1) | 20 (14.6) | 0.493 |

| LVEF > 55% | 239 (63.6) | 147 (61.5) | 92 (67.2) | 0.273 |

| Logistic EuroSCORE, % ± SD | 19.7 ± 12.9 | 20.5 ± 13.1 | 18.4 ± 12.5 | 0.133 |

| Baseline hemoglobin, g/dL ± SD | 11.9 ± 1.7 | 11.0 ± 1.1 | 13.6 ± 1.1 | < 0.001 |

| Baseline RDW, % ± SD | 15.0 ± 1.8 | 15.4 ± 1.8 | 14.4 ± 1.6 | < 0.001 |

| Baseline serum creatinine, mg/dL ± SD | 1.3 ± 1.1 | 1.5 ± 1.2 | 1.0 ± 0.5 | < 0.001 |

| Baseline GFR, mL/min ± SD | 58.7 ± 23.7 | 54.5 ± 23.6 | 65.9 ± 22.2 | < 0.001 |

| Baseline CRP, mg/dL ± SD | 1.2 ± 1.8 | 1.4 ± 2.0 | 0.8 ± 1.1 | < 0.001 |

| TF access | 270 (71.8) | 172 (72.0) | 98 (71.5) | 0.742 |

| TA access | 105 (27.9) | 66 (27.6) | 39 (28.5) | 0.862 |

| TS access | 1 (0.3) | 1 (0.4) | 0 (0.0) | 0.637 |

Serum levels for baseline serum creatinine (anemia: 1.5 mg/dL ± 1.2 mg/dL vs no anemia: 1.0 mg/dL ± 0.5 mg/dL; P < 0.001) and C-reactive Protein (anemia: 1.4 mg/dL ± 2.0 mg/dL vs no anemia: 0.8 mg/dL ± 1.1 mg/dL; P < 0.001) were higher in patients with anemia whereas baseline creatinine clearance was lower in anemic patients (54.5 mL/min ± 23.6 mL/min vs 65.9 mL/min ± 22.2 mL/min; P < 0.001). As a marker for the variability in size of the circulating erythrocytes the RDW was higher in patients with anemia (15.4% ± 1.8% vs 14.4% ± 1.6%; P < 0.001).

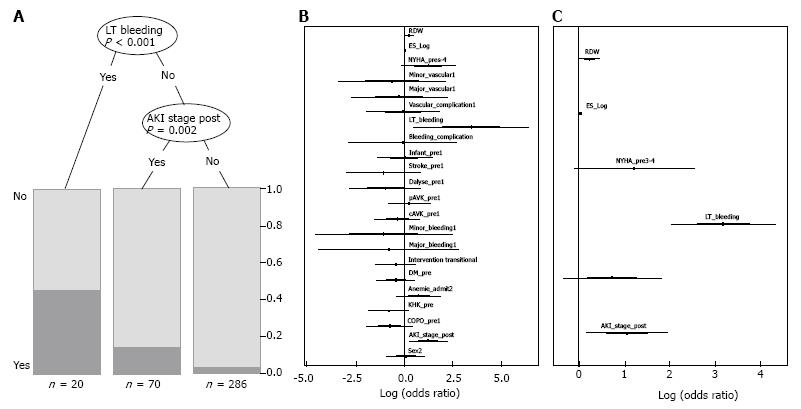

Clinical outcome was reported according to VARC criteria[29]. The findings are summarized in Table 2. There was no difference with regard to vascular or bleeding complications in between both groups. Overall incidence of acute kidney injury (AKI) after TAVI was higher in patients with anemia (25.1% vs 10.9%; P = 0.001). Further clinical endpoints as stroke (anemia: 2.9% vs no anemia: 2.2%; P = 0.668), myocardial infarction (anemia: 0.4% vs no anemia: 0.0%; P = 0.448), endocarditis (anemia: 0.0% vs no anemia: 0.0%) and need for permanent pacemaker after TAVI (anemia: 21.3% vs no anemia: 19.0%; P = 0.585) did not differ between the groups. The incidence of a septical event was higher in patients with anemia (8.4% vs 2.2%; P = 0.016). Overall 30-d mortality was 7.2% (n = 27). In patients with anemia 30-d mortality was 9.2% (n = 22) whereas 3.6% (n = 5) of the patients without anemia died within 30 d (P = 0.045). The partitioning regression analysis, displayed as a classification tree, showed that life-threatening bleeding (P < 0.001) after TAVI and occurrence of AKI (P = 0.002) were statistically relevant risk factors for 30-d mortality (Figure 1A). Stepwise multiple logistic regression analysis with all covariables and the best selected covariables (Figure 1B and C) confirmed these findings and showed that RDW was a statistically significant risk factor as well (P = 0.044).

| Entire cohort (n = 376) | Anemia (n = 239) | No anemia (n = 137) | P-value | |

| Vascular complications | ||||

| Any vascular complications | 34 (9.0) | 24 (10.0) | 10 (7.3) | 0.372 |

| Minor vascular complications | 20 (5.3) | 14 (5.9) | 6 (4.4) | 0.639 |

| Major vascular complications | 4 (1.1) | 3 (1.3) | 1 (0.7) | 0.633 |

| Bleeding complications | ||||

| Any bleeding complications | 45 (12.0) | 27 (11.3) | 18 (13.1) | 0.596 |

| Life-threatening bleeding | 20 (5.3) | 12 (5.0) | 8 (5.8) | 0.732 |

| Minor bleeding | 21 (5.6) | 12 (5.0) | 9 (6.6) | 0.529 |

| Major bleeding | 4 (1.1) | 3 (1.3) | 1 (0.7) | 0.633 |

| Percutaneous closure device failure | 10 (2.7) | 7 (2.9) | 3 (2.2) | 0.668 |

| Acute kidney injury | 75 (31.4) | 60 (25.1) | 15 (10.9) | 0.001 |

| Acute kidney injury stage I | 44 (11.7) | 33 (13.8) | 11 (8.0) | 0.093 |

| Acute kidney injury stage II | 1 (0.3) | 1 (0.4) | 0 (0.0) | 0.636 |

| Acute kidney injury stage III | 30 (8.0) | 26 (10.9) | 4 (2.9) | 0.007 |

| Need for dialysis | 22 (5.9) | 18 (7.5) | 4 (2.9) | 0.069 |

| Myocardial infaction | 1 (0.3) | 1 (0.4) | 0 (0.0) | 0.448 |

| Stroke | 10 (2.7) | 7 (2.9) | 3 (2.2) | 0.668 |

| Conversion to open surgery | 8 (2.1) | 6 (2.5) | 2 (1.5) | 0.497 |

| Sepsis | 23 (6.1) | 20 (8.4) | 3 (2.2) | 0.016 |

| Endocarditis | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Need for pacemaker | 77 (20.5) | 51 (21.3) | 26 (19.0) | 0.585 |

| Length of stay > 14 d | 235 (62.5) | 152 (63.6) | 83 (60.6) | 0.561 |

| 30-d mortality | 27 (7.2) | 22 (9.2) | 5 (3.6) | 0.045 |

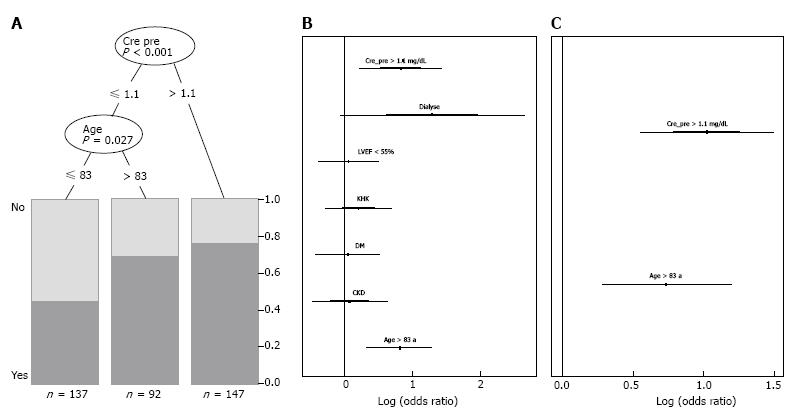

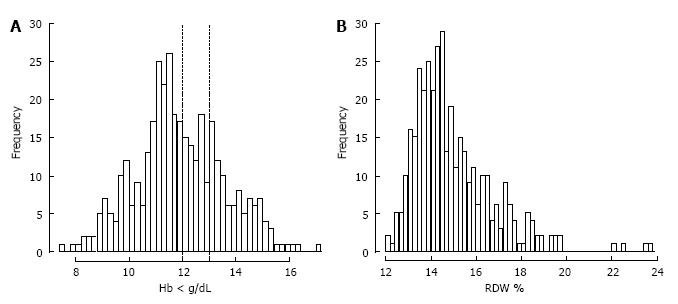

The partitioning regression analysis using anemia as outcome parameter showed that a creatinine level > 1.1 mg/dL (P < 0.001) and age > 83 years (P = 0.027) were statistically relevant risk factors for anemia (Figure 2A). Stepwise multiple logistic regression analysis with all covariables and the best selected covariables confirmed these findings (Figure 2B and C). Mean Hb concentration in our study population was 11.9 g/dL ± 1.7 g/dL. In Figure 3A the distribution of Hb levels in our study population and marking lines for cut-off points defining anemia based on the WHO definition is shown. The distribution of RDW as a marker for the variability and function of circulating erythrocytes is shown in Figure 3B.

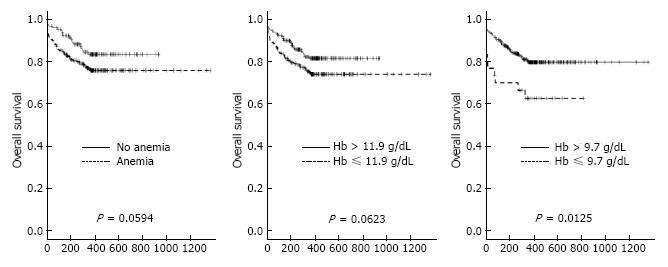

One-year follow up was completed in 100% (n = 376) of patients. The Kaplan-Meier survival curves for one-year mortality in patients with and without anemia are shown in Figure 4A. As the mean Hb concentration in our study population was 11.9 g/dL, the 1-year survival of patients grouped according to their Hb below or above this value is shown in Figure 4B. To find the best hemoglobin cut-off point to predict One-year mortality we performed a partitioning regression analysis which found a hemoglobin of 9.7 g/dL to be the optimal cut-off point (P = 0.012). The Kaplan-Meier survival curves of patients grouped according to their hemoglobin level above or below this cut-off point is shown in Figure 4C.

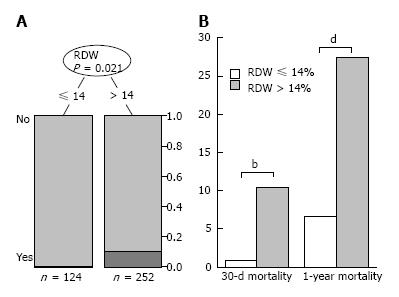

As already described, RDW was found to be a risk factor for 30-d mortality in our study population. The partitioning regression analysis using 30-d mortality as an outcome parameter showed a RDW cut-off point of 14% to predict 30-d mortality with the highest sensitivity and specificity (Figure 5A). In patients with RDW > 14% 30-d mortality and one-year mortality was significantly higher than in patients with a RDW < 14% (Figure 5B).

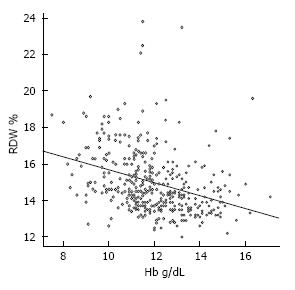

To assess the association between hemoglobin and RDW we performed a correlation analysis (Figure 6) which revealed a significant negative correlation between hemoglobin and RDW (-0.36; 95%CI: -0.45, -0.27; P < 0.001) reflecting that an increasing severity of anemia is associated with an increased heterogeneity of red blood cell size.

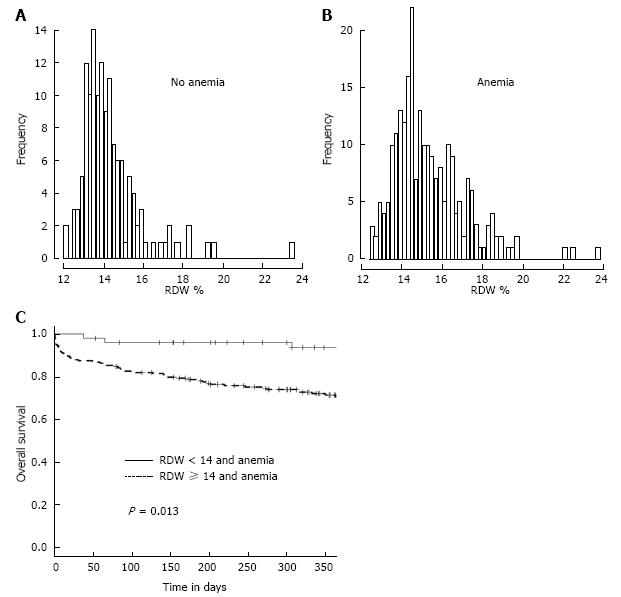

RDW has been shown to be elevated in conditions of ineffective RBC production[19]. In our study population, anemic patients presented with a higher RDW than patients without anemia (P < 0.001). The distribution of RDW levels in patients with and without anemia is shown in Figure 7A and B. The Kaplan-Meier survival curves of anemic patients grouped according to the presence of a RDW below or above 14% are shown in Figure 7C (P = 0.013).

The major findings of the present study are: (1) two thirds of TAVI patients are anemic according to the WHO definition; (2) age and level of creatinine determine independently the incidence of anemia in this population; (3) anemia affects incidence of TAVI related kidney injury and 30 d mortality according to VARC criteria for short term outcome; (4) a lower threshold of Hb (9.7 mg/dL) predicts 1 year mortality more precisely than the classical WHO definition of anemia in this patient cohort in our study; (5) absolute levels of hemoglobin are related only loosely to size, distribution and presumably function of red blood cells; and (6) a red blood cell distribution width of > 14% is highly predictable for a reduced rate of survival in patients with aortic valve disease one year after TAVI procedure, particularly in those patients with already preexisting anemia. These findings raise the question whether or not the RDW should be integrated in the risk stratification in elderly anemic patients undergoing TAVI procedure.

In elderly patients with aortic valve disease the age and the kidney function are the major predictors on the prevalence of anemia, which is similar to reports in patients with CAD and CHF[1,3]. Kidney function deteriorates with increasing age and the number of circulating RBC is critically dependent on the axis of renal stimulation of bone marrow synthesis of erythrocytes. According to the definition of the WHO, anemia was common in elderly patients with aortic valve stenosis and the mean value of hemoglobin level in the entire cohort was only 11.9 g/dL. Both the threshold levels suggested by the WHO and the mean value of Hb failed to precisely discriminate those patients at increased or reduced mortality rate in our study cohort. Only a level of < 9.7 g/dL hemoglobin identified patients with a reduced survival at one year after TAVI. This finding is in line with previous reports on an increased mortality one year after TAVI with decreasing levels of hemoglobin[7]. These data imply that categorizing patients as anemic or non-anemic according to the WHO criteria might be helpful to stratify patients undergoing TAVI for their periprocedural risk and short term survival, whereas long term mortality and overall risk is better achieved with a threshold of < 10 g/dL of hemoglobin.

The major task of erythrocytes is to deliver oxygen required to meet metabolic demands to tissues. Apart from the hemoglobin-dependent transport of oxygen, RBC serve many other functions. Number and distribution of RBC in the circulation are determined by their membrane and erythrocrine function[33-35]. Alterations of the redox status and the conformation of membrane regulate their shape, their distribution, passage through the microcirculation and their removal from the circulation by the reticulo-endothelial. RBC release ATP, NO, nitrite, prostanoids, chemo kinins and sulfide[36]. More recently we and others have shown that RBCs modulate their deformability, vascular tone, infarct size and thrombus formation at the endothelium through NOS/sGC signaling[37-40]. The RBC deformability and the rapid shape change are of paramount importance for the passage through the microcirculation and effective tissue perfusion. An increased RDW is associated with an impairment of RBC deformability[19]. These data may raise concerns with the view that sole measurements of hemoglobin levels reflect appropriately consequences of anemia and their impact on outcome in cardiovascular diseases and interventions.

The distribution and width of RBC as a novel marker for adverse outcome in CHF has been described in the cohort of the CHARM trial only recently[20]. Among 36 routine laboratory values including hematocrit and hemoglobin, higher RDW showed the greatest association with morbidity and mortality. Given the association of hemoglobin with adverse outcome in CHF and CAD we evaluated the relationship of RDW and level of hemoglobin (Figure 6). We observed a moderate negative correlation as was also reported for CHF[20]. In all final multivariate models RDW was a significant predictor of short term outcome after TAVI.

Age and kidney function determine the degree of anemia. The anios cytosis of red blood cells in anemic patients is emerging as an important parameter to assess short and long term mortality in patients undergoing TAVI. These findings demonstrate that RDW supplements prognostic information in addition to that derived from the WHO-based definition of anemia.

Our results have to be confirmed in larger cohorts with a longer follow up period to establish RDW as an independent and powerful prognostic marker in elderly patients with structural heart disease. In our retrospective single center cohort study we did not systematically substitute anemia with packed red blood cells and left this decision at the discretion of the interventionalists and the colleagues supervising the patients after the TAVI procedure on the ICU and the regular ward. However, we did focus on the Hb levels and RDW at the time of admittance prior to the TAVI procedure and the percentage of patients that received transfusion within the hospital was comparable in the anemic and the non-anemic group. Therefore, we believe that this did not affect outcome differences with respect to RDW (prior to TAVI) between both groups. Further, we did not investigate the treatment of anemic patients and patients with chronic kidney disease which may have been an interesting aspect.

In addition mechanistic studies focusing on RBC signaling cascades that might be altered in these elderly patients appear highly mandatory to identify potential novel therapeutic targets to improve RBC function and to determine how treatment of anemia should be guided and monitored in this elderly population with aortic valve disease.

Anemia is common in elderly patients with cardiovascular disease. An association of increased mortality with decreasing levels of hemoglobin has been shown in patients with coronary artery disease, acute myocardial infarction, cardiac heart failure and structural heart disease. Red blood cell (RBC) distribution width (RDW) is a quantitative measure of anisocytosis, the variability in size of circulating RBC. It may represent an integrative measure of multiple pathologic processes in the elderly patient with structural heart disease, explaining its strong association with clinical short and long term outcomes. Recent studies indicate that the detrimental effects of anemia are not only mediated by the absolute hemoglobin levels, but also by the quality of the endogenous and the substituted RBCs. The role of RDW in anemic patients undergoing TAVI is not clear. The authors therefore investigated whether RDW may have the potential to act as a novel prognostic parameter for risk stratification in addition to anemia, as defined by WHO criteria.

Red cell distribution width has been shown to be a novel marker not only of the size of erythrocytes, but also as an index of quality and function of RBC. It has been shown to be a powerful and independent predictor of mortality in cardiac heart failure. The results of this study contributes to evaluate the impact of prevalent anemia on outcome and to clarify the prognostic value of RDW in anemic TAVI patients.

In this study, anemia was prevalent 63.6% of the patients and did influence 30-d mortality but did not predict longterm mortality. In contrast, a RDW > 14% showed to be highly predictable for a reduced short- and long-term survival in patients with aortic valve disease after TAVI procedure. Age and creatinine were identified as risk factors for anemia.

This study suggests that RDW is a useful additional parameter which gives prognostic information concerning the outcome of anemic patients undergoing transcatheter aortic valve implantation.

Red cell distribution width (RDW): RDW is a quantitative measure of anisocytosis, the variability in size of circulating RBC. It has been shown to be a novel marker not only of the size of erythrocytes, but also as an index of quality and function of RBC.

The paper is well structured, the presentation is clear and the discussion is in accordance with the results presented. The paper brings some novelty in the field.

P- Reviewer: Feher G, Ivanovski P, Medeiros M, Prasetyo AA S- Editor: Ji FF L- Editor: A E- Editor: Lu YJ

| 1. | Anker SD, Voors A, Okonko D, Clark AL, James MK, von Haehling S, Kjekshus J, Ponikowski P, Dickstein K. Prevalence, incidence, and prognostic value of anaemia in patients after an acute myocardial infarction: data from the OPTIMAAL trial. Eur Heart J. 2009;30:1331-1339. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 60] [Cited by in RCA: 79] [Article Influence: 4.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Salisbury AC, Alexander KP, Reid KJ, Masoudi FA, Rathore SS, Wang TY, Bach RG, Marso SP, Spertus JA, Kosiborod M. Incidence, correlates, and outcomes of acute, hospital-acquired anemia in patients with acute myocardial infarction. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2010;3:337-346. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 68] [Cited by in RCA: 85] [Article Influence: 5.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Anand IS. Anemia and chronic heart failure implications and treatment options. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2008;52:501-511. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 206] [Cited by in RCA: 224] [Article Influence: 13.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Sabatine MS, Morrow DA, Giugliano RP, Burton PB, Murphy SA, McCabe CH, Gibson CM, Braunwald E. Association of hemoglobin levels with clinical outcomes in acute coronary syndromes. Circulation. 2005;111:2042-2049. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 459] [Cited by in RCA: 509] [Article Influence: 25.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Kulier A, Levin J, Moser R, Rumpold-Seitlinger G, Tudor IC, Snyder-Ramos SA, Moehnle P, Mangano DT. Impact of preoperative anemia on outcome in patients undergoing coronary artery bypass graft surgery. Circulation. 2007;116:471-479. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 327] [Cited by in RCA: 341] [Article Influence: 18.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Bassand JP, Afzal R, Eikelboom J, Wallentin L, Peters R, Budaj A, Fox KA, Joyner CD, Chrolavicius S, Granger CB. Relationship between baseline haemoglobin and major bleeding complications in acute coronary syndromes. Eur Heart J. 2010;31:50-58. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 57] [Cited by in RCA: 69] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Nuis RJ, Sinning JM, Rodés-Cabau J, Gotzmann M, van Garsse L, Kefer J, Bosmans J, Yong G, Dager AE, Revilla-Orodea A. Prevalence, factors associated with, and prognostic effects of preoperative anemia on short- and long-term mortality in patients undergoing transcatheter aortic valve implantation. Circ Cardiovasc Interv. 2013;6:625-634. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 63] [Cited by in RCA: 76] [Article Influence: 6.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Nutritional anaemias. Report of a WHO scientific group. World Health Organ Tech Rep Ser. 1968;405:5-37. [PubMed] |

| 9. | Cladellas M, Farré N, Comín-Colet J, Gómez M, Meroño O, Bosch MA, Vila J, Molera R, Segovia A, Bruguera J. Effects of preoperative intravenous erythropoietin plus iron on outcome in anemic patients after cardiac valve replacement. Am J Cardiol. 2012;110:1021-1026. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 72] [Cited by in RCA: 81] [Article Influence: 6.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Najjar SS, Rao SV, Melloni C, Raman SV, Povsic TJ, Melton L, Barsness GW, Prather K, Heitner JF, Kilaru R. Intravenous erythropoietin in patients with ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction: REVEAL: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2011;305:1863-1872. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 181] [Cited by in RCA: 176] [Article Influence: 12.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Macdougall IC, Provenzano R, Sharma A, Spinowitz BS, Schmidt RJ, Pergola PE, Zabaneh RI, Tong-Starksen S, Mayo MR, Tang H. Peginesatide for anemia in patients with chronic kidney disease not receiving dialysis. N Engl J Med. 2013;368:320-332. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 82] [Cited by in RCA: 84] [Article Influence: 7.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Swedberg K, Young JB, Anand IS, Cheng S, Desai AS, Diaz R, Maggioni AP, McMurray JJ, O’Connor C, Pfeffer MA. Treatment of anemia with darbepoetin alfa in systolic heart failure. N Engl J Med. 2013;368:1210-1219. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 376] [Cited by in RCA: 465] [Article Influence: 38.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Nikolsky E, Mehran R, Sadeghi HM, Grines CL, Cox DA, Garcia E, Tcheng JE, Griffin JJ, Guagliumi G, Stuckey T. Prognostic impact of blood transfusion after primary angioplasty for acute myocardial infarction: analysis from the CADILLAC (Controlled Abciximab and Device Investigation to Lower Late Angioplasty Complications) Trial. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2009;2:624-632. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 57] [Cited by in RCA: 59] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Shishehbor MH, Madhwal S, Rajagopal V, Hsu A, Kelly P, Gurm HS, Kapadia SR, Lauer MS, Topol EJ. Impact of blood transfusion on short- and long-term mortality in patients with ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2009;2:46-53. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 52] [Cited by in RCA: 54] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Koch CG, Li L, Sessler DI, Figueroa P, Hoeltge GA, Mihaljevic T, Blackstone EH. Duration of red-cell storage and complications after cardiac surgery. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:1229-1239. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1020] [Cited by in RCA: 996] [Article Influence: 58.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Donadee C, Raat NJ, Kanias T, Tejero J, Lee JS, Kelley EE, Zhao X, Liu C, Reynolds H, Azarov I. Nitric oxide scavenging by red blood cell microparticles and cell-free hemoglobin as a mechanism for the red cell storage lesion. Circulation. 2011;124:465-476. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 470] [Cited by in RCA: 472] [Article Influence: 33.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Doyle BJ, Rihal CS, Gastineau DA, Holmes DR. Bleeding, blood transfusion, and increased mortality after percutaneous coronary intervention: implications for contemporary practice. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009;53:2019-2027. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 309] [Cited by in RCA: 313] [Article Influence: 19.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Rainer C, Kawanishi DT, Chandraratna PA, Bauersachs RM, Reid CL, Rahimtoola SH, Meiselman HJ. Changes in blood rheology in patients with stable angina pectoris as a result of coronary artery disease. Circulation. 1987;76:15-20. [PubMed] |

| 19. | Patel KV, Mohanty JG, Kanapuru B, Hesdorffer C, Ershler WB, Rifkind JM. Association of the red cell distribution width with red blood cell deformability. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2013;765:211-216. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 113] [Cited by in RCA: 153] [Article Influence: 12.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Felker GM, Allen LA, Pocock SJ, Shaw LK, McMurray JJ, Pfeffer MA, Swedberg K, Wang D, Yusuf S, Michelson EL. Red cell distribution width as a novel prognostic marker in heart failure: data from the CHARM Program and the Duke Databank. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2007;50:40-47. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 587] [Cited by in RCA: 696] [Article Influence: 38.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Aung N, Ling HZ, Cheng AS, Aggarwal S, Flint J, Mendonca M, Rashid M, Kang S, Weissert S, Coats CJ. Expansion of the red cell distribution width and evolving iron deficiency as predictors of poor outcome in chronic heart failure. Int J Cardiol. 2013;168:1997-2002. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 53] [Cited by in RCA: 64] [Article Influence: 5.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Magri CJ, Chieffo A, Durante A, Latib A, Montorfano M, Maisano F, Cioni M, Agricola E, Covello RD, Gerli C. Impact of mean platelet volume on combined safety endpoint and vascular and bleeding complications following percutaneous transfemoral transcatheter aortic valve implantation. Biomed Res Int. 2013;2013:645265. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Aung N, Dworakowski R, Byrne J, Alcock E, Deshpande R, Rajagopal K, Brickham B, Monaghan MJ, Okonko DO, Wendler O. Progressive rise in red cell distribution width is associated with poor outcome after transcatheter aortic valve implantation. Heart. 2013;99:1261-1266. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Magri CJ, Chieffo A, Latib A, Montorfano M, Maisano F, Cioni M, Agricola E, Covello RD, Gerli C, Franco A. Red blood cell distribution width predicts one-year mortality following transcatheter aortic valve implantation. Int J Cardiol. 2014;172:456-457. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Shishehbor MH, Filby SJ, Chhatriwalla AK, Christofferson RD, Jain A, Kapadia SR, Lincoff AM, Bhatt DL, Ellis SG. Impact of drug-eluting versus bare-metal stents on mortality in patients with anemia. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2009;2:329-336. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Lippi G, Salvagno GL, Guidi GC. Red blood cell distribution width is significantly associated with aging and gender. Clin Chem Lab Med. 2014;52:e197-e199. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Cockcroft DW, Gault MH. Prediction of creatinine clearance from serum creatinine. Nephron. 1976;16:31-41. [PubMed] |

| 28. | Levey AS, Eckardt KU, Tsukamoto Y, Levin A, Coresh J, Rossert J, De Zeeuw D, Hostetter TH, Lameire N, Eknoyan G. Definition and classification of chronic kidney disease: a position statement from Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO). Kidney Int. 2005;67:2089-2100. [PubMed] |

| 29. | Kappetein AP, Head SJ, Généreux P, Piazza N, van Mieghem NM, Blackstone EH, Brott TG, Cohen DJ, Cutlip DE, van Es GA. Updated standardized endpoint definitions for transcatheter aortic valve implantation: the Valve Academic Research Consortium-2 consensus document. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2013;145:6-23. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 644] [Cited by in RCA: 733] [Article Influence: 56.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Vahanian A, Alfieri O, Andreotti F, Antunes MJ, Baron-Esquivias G, Baumgartner H, Borger MA, Carrel TP, De Bonis M, Evangelista A. [Guidelines on the management of valvular heart disease (version 2012). The Joint Task Force on the Management of Valvular Heart Disease of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) and the European Association for Cardio-Thoracic Surgery (EACTS)]. G Ital Cardiol (Rome). 2013;14:167-214. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Hothorn T, Hornik K, Zeileis A. Unbiased Recursive Partitioning: A Conditional Inference Framework. J Comput Graph Stat. 2006;15:651-674. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2216] [Cited by in RCA: 1568] [Article Influence: 82.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Shavit L, Hitti S, Silberman S, Tauber R, Merin O, Lifschitz M, Slotki I, Bitran D, Fink D. Preoperative hemoglobin and outcomes in patients with CKD undergoing cardiac surgery. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2014;9:1536-1544. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Sprague RS, Bowles EA, Achilleus D, Ellsworth ML. Erythrocytes as controllers of perfusion distribution in the microvasculature of skeletal muscle. Acta Physiol (Oxf). 2011;202:285-292. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 46] [Cited by in RCA: 44] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Mohandas N, Gallagher PG. Red cell membrane: past, present, and future. Blood. 2008;112:3939-3948. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 654] [Cited by in RCA: 669] [Article Influence: 39.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Lutz HU, Bogdanova A. Mechanisms tagging senescent red blood cells for clearance in healthy humans. Front Physiol. 2013;4:387. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 106] [Cited by in RCA: 148] [Article Influence: 12.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Cortese-Krott MM, Kelm M. Endothelial nitric oxide synthase in red blood cells: key to a new erythrocrine function? Redox Biol. 2014;2:251-258. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 111] [Cited by in RCA: 140] [Article Influence: 12.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Wood KC, Cortese-Krott MM, Kovacic JC, Noguchi A, Liu VB, Wang X, Raghavachari N, Boehm M, Kato GJ, Kelm M. Circulating blood endothelial nitric oxide synthase contributes to the regulation of systemic blood pressure and nitrite homeostasis. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2013;33:1861-1871. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 99] [Cited by in RCA: 101] [Article Influence: 8.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | Cortese-Krott MM, Rodriguez-Mateos A, Sansone R, Kuhnle GG, Thasian-Sivarajah S, Krenz T, Horn P, Krisp C, Wolters D, Heiß C. Human red blood cells at work: identification and visualization of erythrocytic eNOS activity in health and disease. Blood. 2012;120:4229-4237. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 121] [Cited by in RCA: 150] [Article Influence: 11.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | Merx MW, Gorressen S, van de Sandt AM, Cortese-Krott MM, Ohlig J, Stern M, Rassaf T, Gödecke A, Gladwin MT, Kelm M. Depletion of circulating blood NOS3 increases severity of myocardial infarction and left ventricular dysfunction. Basic Res Cardiol. 2014;109:398. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 46] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 40. | Yang J, Gonon AT, Sjöquist PO, Lundberg JO, Pernow J. Arginase regulates red blood cell nitric oxide synthase and export of cardioprotective nitric oxide bioactivity. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2013;110:15049-15054. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 119] [Cited by in RCA: 125] [Article Influence: 10.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |