Published online Nov 26, 2016. doi: 10.4330/wjc.v8.i11.676

Peer-review started: June 17, 2016

First decision: July 27, 2016

Revised: August 16, 2016

Accepted: September 7, 2016

Article in press: September 8, 2016

Published online: November 26, 2016

Processing time: 162 Days and 22.5 Hours

To study survival in isolated coronary artery bypass graft (CABG) patients and to evaluate the impact of preoperative chronic opium consumption on long-term outcome.

Cohort of 566 isolated CABG patients as Tehran Heart Center cardiac output measurement was conducted. Daily evaluation until discharge as well as 4- and 12-mo and 6.5-year follow-up information for survival status were fulfilled for all patients. Long-term 6.5-year overall and opium-stratified survival, adjusted survival curves based on opium consumption as well as possible predictors of all-cause mortality using multiple cox regression were determined by statistical analysis.

Six point five-year overall survival was 91.8%; 86.6% in opium consumers and 92.7% in non-opium consumers (P = 0.035). Patients with positive history of opium consumption significantly tended to have lower ejection fraction (EF), higher creatinine level and higher prevalence of myocardial infarction. Multiple predictors of all-cause mortality included age, body mass index, EF, diabetes mellitus and cerebrovascular accident. The hazard ratio (HR) of 2.09 for the risk of mortality in opium addicted patients with a borderline P value (P = 0.052) was calculated in this model. Further adjustment with stratification based on smoking and opium addiction reduced the HR to 1.20 (P = 0.355).

Simultaneous impact of smoking as a confounding variable in most of the patients prevents from definitive judgment on the role of opium as an independent contributing factor in worse long-term survival of CABG patients in addition to advanced age, low EF, diabetes mellitus and cerebrovascular accident. Meanwhile, our findings do not confirm any cardio protective role for opium to improve outcome in coronary patients with the history of smoking. Further studies are needed to clarify pure effect of opium and warrant the aforementioned findings.

Core tip: A significant percentage of coronary artery disease patients undergo cardiac surgery so defining outcome predictors is essential for risk calculation and is necessary for estimation of resource utilization and provision of services. Employing global knowledge on this issue is not justified without adjustment for regional specifications and needs. This study aimed at clarifying the role of opium addiction in predicting long-term mortality of coronary artery bypass graft surgery in addition to advanced age, low ejection fraction, diabetes mellitus and cerebrovascular accident.

- Citation: Najafi M, Jahangiry L, Mortazavi SH, Jalali A, Karimi A, Bozorgi A. Outcomes and long-term survival of coronary artery surgery: The controversial role of opium as risk marker. World J Cardiol 2016; 8(11): 676-683

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1949-8462/full/v8/i11/676.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4330/wjc.v8.i11.676

Growing number of patients undergoing coronary artery bypass graft (CABG) surgery all over the world[1], justifies studying on possible predicting factors of clinical outcomes such as short and long-term survival. There are published reports of some predictive factors responsible for short-term mortality such as advanced age, previous history of cardiac surgery and myocardial infarction, non-cardiac comorbidities, New York Heart Association functional class (FC) III or IV and serum creatinine (Cr) level[2,3]. Also some additional factors have been suggested for intermediate-term mortality including left ventricular ejection fraction (EF) and history of percutaneous coronary stenting[2,4]. Similarly, long-term survival could be influenced by diabetes mellitus[5], hypoalbuminemia[6], female gender, smoking, cardiogenic shock[7] and severe preoperative renal dysfunction[3,8].

Coronary artery disease (CAD) has a high prevalence in Iranian population, affecting 22.2% of men and 37.5% of women[9]. In addition, opium is the major abused substance in Iran[10] and the prevalence of opium addiction is believed to be higher in CAD patients undergoing revascularization[11]. The predictive role of opium in short-term outcomes of patients undergoing CABG is controversial. Some investigations have suggested cardiac protective role for opium during ischemic events[12,13]. In a propensity-matched study, Sadeghian et al[14] found no association between opium dependence and post CABG in-hospital complications. On the other hand, in Safaii et al[15]’s study, six months post-CABG readmission was significantly more frequent in opium users. However, there are few evidences to clarify the definite relationship between chronic opium abuse and long-term survival in cardiac surgery patients.

So not only there is limited knowledge regarding the adverse impact of opium consumption on long-term survival of CABG patients, but also the available studies on short-term outcomes have shown controversial results. Therefore in this study we aimed to assess the impact of chronic opium consumption on long-term survival of patients who underwent isolated CABG in a cardiac tertiary center.

In the present cohort study (Tehran Heart Center Cardiac Output Measurement)[16], 566 consecutive CAD patients who underwent isolated CABG during six months (April 2006-September 2006) at THC, a high-volume specialized heart tertiary care center, were identified and after signing the informed consent were entered the study. Exclusion criteria were concomitant replacement or repair of heart valve, ventricular aneurism resection or any surgeries other than CABG.

Patients’ demographic characteristics including age, gender, weight, waist circumference, body mass index (BMI) as well as their initial laboratory measurements were recorded in previously defined data sheets and were completed from THC surgery database[17] in case of missing information. Family and drug history, associated comorbidities, habitual habits, FC and left ventricular EF were also among documented variables. Regular daily consumption of opium along with fulfilling DSM-IV-TR criteria for opium dependence was considered for opium addiction[11,18].

EuroSCORE was also calculated for all study population and were categorized as low risk (0-2), medium risk (3-5), high risk (6-8) and very high risk (≥ 9) based on what has been previously reported in literature[19,20].

CABG Patients were followed at 4 and 12 mo following the operation through the organized regular visits at CABG follow-up clinic or by telephone interviews. Meanwhile, any outpatient or inpatient services thereafter are recorded precisely in patients’ electronic medical file at our institution by the initial unique code. But for the specific purpose of our study in evaluation of long-term survival, we contacted patients by telephone to attend at hospital to be followed 7 years after the cardiac surgery. The precise date of patients’ attendance was recorded.

In these long-term follow-up sessions, all patients were investigated for survival status. FC and EF along with further laboratory assessments were also assessed. For non-responders, mortality tracking as well as the exact time and to somehow the etiology of death was noted through telephone interviews with patients’ relatives or by checking up the online registration of deaths. For surviving non-responders, the last attendance at THC for receiving any services was considered as the last time of follow-up. The latter group was defined as incomplete follow-up.

Continuous variables were presented as mean and standard deviation (SD) or median with 25th and 75th percentiles, and were compared between two groups of opium usage using independent samples t or Mann-Whitney U test. Categorical variables were expressed as frequency and percentage and were compared between aforementioned groups applying χ2 or Fisher’s exact test. Survival probabilities were estimated using Kaplan-Meier method and their 95%CI were calculated through log-transformed method. The univariate effect of variables on long-term mortality was evaluated using Cox proportional hazards (PH) regression. All variables with P values less than 0.2 in the univariate analysis were candidate to enter the multivariable model. A backward stepwise Cox PH model, with removal and entry probabilities as 0.1 and 0.05 respectively, was applied to find the multiple predictors of long-term mortality. The PH assumption was checked through the χ2 test of the correlation coefficient between transformed survival time and scaled Schoenfeld residuals. Those variables which simultaneously associated with opium usage and long-term mortality with P values less than 0.2 were detected as potential confounders. The effect of opium on long-term mortality adjusted for potential confounders was assessed using Cox PH model. All effects on long-term mortality were reported through hazards ratio (HR) with 95%CI. Softwares IBM SPSS statistics for windows version 22 (Armonk, NY: IBM Corp.) and STATA (StataCorp. 2013. Stata Statistical Software: Release 13. College Station, TX: StataCorp LP.) were used to conduct the analyses.

Based on findings, among 566 patients, 53 (9.4%) deaths occurred during the 6.5 years of follow-up among which 40.9% was cardiac and 59.1% was of non-cardiac cause. Median follow-up time for all of the study population was 78.7 mo (95%CI: 78.5-78.9). Median (25th-75th interquartile range) follow-up time of 235 patients with incomplete follow-up was 74.6 (25th-75th: 73.5-75.7) mo.

Patients’ demographics characteristics and risk factors: Table 1 demonstrates patients’ baseline demographic and clinical characteristics by survival status. According to univariate analysis, age, blood urea nitrogen and high-density lipoprotein levels were significantly lower and EF, albumin and triglyceride levels were significantly higher among survivors. Moreover, opium consumption, diabetes mellitus, cerebrovascular accident and peripheral vascular disease were significantly more frequent among the expired cases.

| Alive (n = 513) | Dead (n = 53) | Hazard ratio (95%CI) | P value | |

| Age (yr) | 58.5 ± 8.81 | 64.6 ± 8.27 | 1.08 (1.044-1.117) | < 0.001 |

| Gender (male) | 382 (74.5) | 43 (81.1) | 1.425 (0.716-2.837) | 0.313 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 27.4 ± 4.04 | 26.5 ± 4.39 | 0.947 (0.881-1.019) | 0.146 |

| Waist circumference (cm) | 101.3 ± 1.46 | 100.2 ± 2.95 | 0.962 (0.85-1.09) | 0.543 |

| FC | 0.141 | |||

| I | 177 (34.6) | 21 (39.6) | ||

| II | 263 (51.5) | 20 (37.7) | 0.701 (0.379-1.295) | 0.256 |

| III | 71 (13.9) | 12 (22.6) | 1.433 (0.702-2.924) | 0.323 |

| EF (%) | 49.1 ± 10.07 | 42.2 ± 11.07 | 0.94 (0.915-0.965) | < 0.001 |

| FH | 251 (49.1) | 18 (34) | 0.5 (0.282-0.887) | 0.018 |

| Smoking | 183 (35.8) | 20 (37.7) | 0.954 (0.542-1.678) | 0.870 |

| Alcohol | 66 (13.7) | 5 (9.8) | 0.523 (0.201-1.363) | 0.185 |

| Opium | 69 (13.5) | 13 (24.5) | 1.939 (1.032-3.644) | 0.040 |

| DM | 204 (39.9) | 28 (52.8) | 1.789 (1.033-3.097) | 0.038 |

| HLP | 366 (71.6) | 32 (60.4) | 0.58 (0.334-1.008) | 0.053 |

| HTN | 253 (49.5) | 26 (49.1) | 1.033 (0.602-1.774) | 0.906 |

| CVA | 16 (3.1) | 6 (11.3) | 4.146 (1.761-9.76) | 0.001 |

| PVD | 136 (26.6) | 22 (41.5) | 2.166 (1.246-3.766) | 0.006 |

| MI | 254 (49.9) | 32 (61.5) | 1.61 (0.92-2.816) | 0.095 |

| Alb (g/dL) | 4.6 ± 0.32 | 4.5 ± 0.39 | 0.351 (0.16-0.77) | 0.009 |

| FBS | 96 (87-117) | 98 (84-124) | 1.004 (0.997-1.011) | 0.266 |

| BUN | 38 (31-46) | 40 (33-52) | 1.035 (1.016-1.054) | < 0.001 |

| Cr | 1.2 ± 0.27 | 1.3 ± 0.26 | 2.009 (0.832-4.856) | 0.121 |

| Mg | 1.9 ± 0.34 | 1.9 ± 0.39 | 1.15 (0.421-3.143) | 0.785 |

| HCT | 42.3 ± 5.92 | 42.8 ± 3.82 | 1.013 (0.979-1.047) | 0.462 |

| TG | 165 (115-210) | 126 (97-173) | 0.994 (0.990-0.999) | 0.010 |

| Chol | 160 ± 44.86 | 166.3 ± 48.06 | 1.003 (0.997-1.008) | 0.347 |

| LP | 23 (12-45) | 28 (15-54) | 1.006 (0.997-1.016) | 0.191 |

| CRP | 5.75 (4.9-7) | 6.35 (4.82-8.57) | 1.001 (0.99-1.013) | 0.814 |

| LDL | 82 (59-105) | 86 (68-114) | 1.003 (0.997-1.009) | 0.280 |

| HDL | 40.3 ± 8.5 | 42.8 ± 9.37 | 1.031 (1-1.062) | 0.049 |

| No. of diseased vessel | 0.473 | |||

| 1 | 19 (3.7) | 2 (3.8) | ||

| 2 | 99 (19.4) | 7 (13.2) | 0.616 (0.127-2.976) | 0.547 |

| 3 | 393 (76.9) | 44 (83) | 1.013 (0.245-4.191) | 0.985 |

| No. of grafts | 3.7 ± 0.94 | 3.9 ± 1.02 | 1.234 (0.922-1.650) | 0.158 |

| Euro score | 0.017 | |||

| Low (0-2) | 301 (58.9) | 20 (37.7) | ||

| Moderate (3-5) | 171 (33.5) | 25 (47.2) | 2.089 (1.160-3.762) | 0.014 |

| High (6-8) | 32 (6.3) | 6 (11.3) | 2.851 (1.143-7.110) | 0.025 |

| Very high (≥ 9) | 7 (1.4) | 2 (3.8) | 4.479 (1.044-19.220) | 0.044 |

The frequency of moderate, high and very high risk EuroSCORE was significantly higher in non-survivors as compared to survivors. However, the number of diseased vessels and performed bypass grafts was similar between the both groups.

Table 2 shows patients’ baseline demographic and clinical characteristics generally and based on opium consumption. Mean ± SD age of patients was 59.08 ± 8.9 years and 75.1% were men. History of opium consumption was present in 14.5%. Forty-one percent had diabetes mellitus and 3.9% had history of cerebrovascular accident. Body mass index and EF mean ± SD was 27.3 ± 4.08 kg/m2 and 48.5% ± 10.3%, respectively. Functional class III was documented in 14.7% of patients. Opium users were significantly more often men, younger, smoker and also alcohol consumer.

| All patients (n = 566) | Opium + (n = 82) | Opium - (n = 484) | P value | |

| Age (yr) | 59.08 ± 8.9 | 55.9 ± 8.3 | 59.6 ± 8.9 | < 0.001 |

| Gender (male) | 425 (75.1) | 80 (97.6) | 345 (71.3) | < 0.001 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 27.3 ± 4.08 | 25.7 ± 3.6 | 27.6 ± 4.08 | < 0.001 |

| Waist circumference (cm) | 101.3 ± 11.3 | 100.3 ± 9.3 | 101.5 ± 11.6 | 0.514 |

| FC | 0.531 | |||

| I | 198 (35) | 33 (40.2) | 165 (34.2) | |

| II | 283 (50) | 39 (47.6) | 244 (50.6) | |

| III | 83 (14.7) | 10 (12.2) | 73 (15.1) | |

| EF (%) | 48.5 ± 10.3 | 44.9 ± 9.4 | 49.1 ± 10.3 | 0.001 |

| FH | 269 (47.5) | 44 (53.7) | 225 (46.7) | 0.242 |

| Smoking | 203 (35.9) | 67 (81.7) | 136 (28.2) | < 0.001 |

| Alcohol | 71 (12.5) | 29 (37.7) | 42 (9.2) | < 0.001 |

| DM | 232 (41) | 26 (31.7) | 206 (42.7) | 0.061 |

| HLP | 398 (70.3) | 48 (58.5) | 350 (72.6) | 0.010 |

| HTN | 279 (49.3) | 30 (36.6) | 249 (51.7) | 0.012 |

| CVA | 22 (3.9) | 4 (4.9) | 18 (3.7) | 0.545 |

| PVD | 158 (27.9) | 21 (25.6) | 137 (28.4) | 0.600 |

| MI | 286 (50.5) | 58 (71.6) | 228 (47.5) | < 0.001 |

| Alb (g/dL) | 4.6 ± 0.3 | 4.5 ± 0.3 | 4.6 ± 0.3 | 0.200 |

| FBS | 96 (87-118) | 92 (81-106) | 97 (88-119) | 0.011 |

| BUN | 38 (31-46) | 35 (27-42) | 39 (32-47) | 0.004 |

| Cr | 1.2 ± 0.2 | 1.3 ± 0.3 | 1.2 ± 0.2 | 0.024 |

| Mg | 1.9 ± 0.3 | 1.8 ± 0.3 | 1.9 ± 0.3 | 0.314 |

| HCT | 42.3 ± 5.7 | 42.2 ± 3.6 | 42.4 ± 6.04 | 0.848 |

| TG | 159 (113-205) | 150 (107-194) | 162 (113-208) | 0.353 |

| Chol | 157 (129-186) | 156 (124-177) | 157 (129-188) | 0.167 |

| LP | 23 (12-46) | 24 (9-44) | 23 (13-47) | 0.432 |

| CRP | 5.8 (4.9-7.2) | 5.8 (4.8-7.1) | 5.8 (4.9-7.2) | 0.617 |

| LDL | 83 (60-106) | 85 (60.7-100.5) | 82.5 (60-110) | 0.517 |

| HDL | 40.5 ± 8.6 | 39.4 ± 8.5 | 40.7 ± 8.6 | 0.205 |

| No. of diseased vessel | 0.733 | |||

| 1 | 21 (307) | 2 (2.4) | 19 (3.9) | |

| 2 | 106 (18.7) | 17 (20.7) | 89 (18.5) | |

| 3 | 437 (77.2) | 63 (76.8) | 374 (77.6) | |

| No. of grafts | 4 (3-4) | 4 (3-5) | 4 (3-4) | 0.400 |

| Euro score | 0.199 | |||

| Low (0-2) | 321 (56.7) | 45 (54.9) | 276 (57.3) | |

| Moderate (3-5) | 196 (34.6) | 26 (31.7) | 170 (35.5) | |

| High (6-8) | 38 (6.7) | 10 (12.2) | 28 (5.8) | |

| Very high (≥ 9) | 9 (1.6) | 1 (1.2) | 8 (1.7) |

Patients with positive history of opium consumption also significantly tended to have lower EF (44.9 ± 9.4 vs 49.1 ± 10.3), higher Cr (1.3 ± 0.3 vs 1.2 ± 0.2) and higher prevalence of MI (71.6% vs 47.5%). On the other hand, the level of BMI and fasting blood sugar and prevalence of hyperlipidemia (HLP), hypertension were significantly lower in these patients.

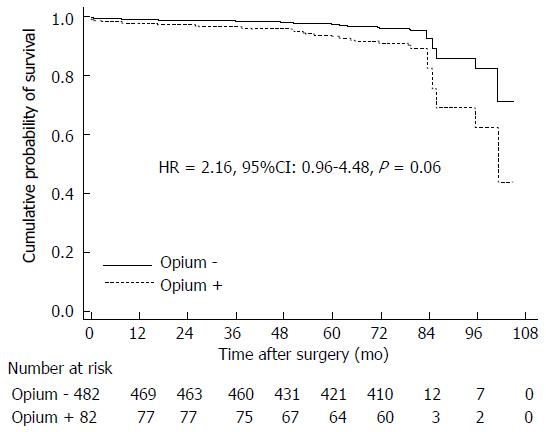

Based on follow-up information, 6.5 years (78.7 mo) overall survival was 91.8% (95%CI: 89.5%-94.2%). When analyzed based on habitual history of opium consumption, 6.5-year (78.7 mo) overall survival was found to be 86.6% (95%CI: 79.1%-94.7%) in opium users and 92.7% (95%CI: 90.3%-95.1%) in non-opium users.

After adjustments for confounding variables such as age, BMI, EF, diabetes, alcohol, HLP, MI, Cr, BUN and EuroSCORE, we found an evidence of predicting mortality for opium with a borderline P value (HR = 2.16; 95%CI: 0.96-4.84; P = 0.06) (Figure 1). As appears from curves, opium users have a trend to worse long-term survival as compared to non-opium consumers.

Multiple Cox regression for predictors of all-cause mortality is described in Table 3. As demonstrated, age, BMI, EF, diabetes mellitus and cerebrovascular accident remained the significant independent predictors of all-cause mortality. We found a trend of increasing risk of all-cause mortality by increasing age and functional class. A converse trend for all-cause mortality was noted by increasing BMI and EF. As shown, cerebrovascular accident had the greatest HR for mortality (HR = 3.45; 95%CI: 1.3-9.1, P = 0.013).

| Hazard ratio (95%CI) | P value | |

| Age (per 10 yr increase) | 2.46 (1.64-3.70) | < 0.001 |

| Opium | 2.09 (0.99-4.39) | 0.052 |

| BMI | 0.89 (0.82-0.96) | 0.004 |

| FC | 0.653 | |

| II vs I | 0.86 (0.44-1.66) | 0.653 |

| III vs II | 2.18 (0.97-4.88) | 0.057 |

| EF (per 5% increase) | 0.71 (0.62-0.81) | < 0.001 |

| DM | 2.97 (1.59-5.54) | 0.001 |

| CVA | 3.45 (1.30-9.16) | 0.013 |

Smoking rate was not significantly different between survivors and non-survivors (Table 1). However, due to high coincidence of smoking and opium addiction (Table 2) we adjusted the results by adding the history of smoking to the list of predictors of long-term mortality which reduced the HR of opium for mortality from 2.09 to 1.20 (95%CI: 0.819-1.745, P = 0.355) (Table 3).

The current study represents the overall and opium-based stratified survival of patients undergoing CABG surgery who were followed-up for a median time of 78.7 mo. The prevalence of opium addiction was found to be 14.5% in our study. To our knowledge, studies are lacking to clarify the long-term effects of opium consumption on survival of patients undergoing CABG surgery. One of the notable points of our study was relatively long duration of follow-up.

Considering overall survival of patients undergoing CABG surgery, we found an overall survival of 91.8% in 6.5 years (78.7 mo). Five-year survival has been reported 72.1% in Yoo et al[21]’s study and Dunning et al[22] identified a ten-year survival of 66%. Meanwhile unadjusted 5 and 10-year survivals have been reported 83.8% and 65% in Filardo et al[1]’s research.

We identified that age, BMI, EF, diabetes mellitus and cerebrovascular accident could independently and significantly predict all-cause mortality of patients undergoing CABG surgery. Findings of Leavitt et al[5], Marcheix et al[23] and Barsness et al[24] support our results in terms of adverse effect of diabetes mellitus on long-term survival. Interestingly cerebrovascular accident had the greatest HR of 3.45 in predicting mortality by multiple Cox regression analysis suggesting that non-cardiac comorbidities may play an important role in patients’ outcomes as well as unfavorable cardiac performance.

We found a significant HR of 0.89 for BMI in predicting overall mortality. Our results were in accordance with those reported in Gruberg et al[25]’s work. They found that overweight or obese patients under CABG have significantly better survival outcomes at 3-year follow-up than those with normal BMI. The phenomenon obesity-mortality paradox which is generally accepted in short term outcome studies is described by better outcome in patients with higher BMI compared to the others. However, there is no consensus in long term investigations as Del Prete et al[26] noted that long-term survival was not significantly different between obese and non-obese patients after making adjustment model (HR = 1.2, P = 0.2). This is partially explained by increasing rate of complications due to major cardiovascular risk factors and substantial re stenosis in grafted coronary arteries by time[27,28]. Though we followed our patients for long period of time we found that BMI was still a predictor of mortality. Low mortality rate in our cohort compared to other studies with similar time intervals that reflect lower risks and complications in our patients could be an explanation. The other reason may be the finding of missed to follow up in a group of our patients which decreases the median time of overall follow-up.

Opium can potentially cause coronary atherosclerosis and increase cardiovascular mortality in different ways. Some metabolic changes by opium that could have deleterious effects on cardiovascular system include: Decreasing plasma testosterone and estrogen, and increasing plasma prolactin, increasing insulin resistance, increasing inflammation as well as oxidative stress, increasing fibrinogen and factor VII, and decreasing apolipoprotein A, increasing the release of nitric oxide and inhibiting production and release of hydrogen peroxide. Moreover, opium can decrease myocardial oxygenation from different ways that could extend infarct size and increase probability of death[29,30].

The role of opium in CAD remains controversial. Masoomi et al[13] showed that opium was an independent risk factor of CAD in non-smoker patients. But findings of Sadeghian et al[14]’s research on 4398 isolated CABG patients and opium dependence rate of 15.6%, found no relationship between post CABG in hospital complications and opium addiction. But on the other hand, in a study conducted by Safaii et al[15] on 6-mo outcomes of CABG patients, opium usage leaded to more readmission following CABG operation.

We found a HR of 2.1 for mortality in opium consumers as compared to patients who did not use opium with a borderline P value of 0.06. Since the rate of smoking is higher among opium-consumers, when we further adjusted the results by smoking, we observed that the role of smoking would be more prominent in predicting mortality so that HR for opium decreased to 1.2. Though our findings are not in favor of any protective role for opium in smoker cardiac patients, there is still no evidence to consider opium as a risk marker for long term survival in this group too.

The main problem with clarifying pure effect of opium on long term outcome in cardiac patients is high co incidence of smoking and opium addiction (Table 2). In deed there were only 15 patients who were opium users and non-smokers in our cohort. We need to perform further investigation to clarify pure effect of opium, because ignoring the adverse effects of opium and attributing any poor clinical outcomes to the smoking alone would be potentially associated with worse consequences.

There are other obstacles to detect the effects of opium on outcome in coronary patients that has been discussed elsewhere[30,31]. Briefly there are variations in self-reported dosage, route of usage, and purity of consumed opium. The other important issue probably would be the reason for beginning opium consumption: recreational or for pain relief[29,30].

In conclusion, in the present study, we found advanced age, low EF, DM and CVA as predictors for long term mortality. However, due to the simultaneous impact of smoking as a confounding variable neither the cardio protective role of opium in ischemic phase suggested in some studies nor its role as a predictor for long-term survival of CABG patients could be justified. Further large sample size studies are needed to clarify pure opium role and verify the aforementioned findings.

Cardiovascular diseases especially coronary artery disease have been known causes of morbidity and mortality all over the world. Though most of predictive factors of outcome in coronary artery bypass surgery are common among different countries, there are ethnic, environmental, and psychosocial specifications that necessitate separate studies on predictors of outcome in different parts of the world. Opium consumption is a controversial topic with regard to its impact on coronary artery disease outcome. Current literature is not conclusive about short term mortality and there is paucity of data on the role of opium as a risk marker for long term survival after coronary artery bypass surgery.

A large cohort in normal population revealed that opium consumption has been associated with increased all cause and cardiovascular mortality. Some studies are focused on the pattern of obesity impact on outcome in cardiovascular disease. Finding a mixed group of factors including risk markers and a panel of biomarkers with the highest level of outcome prediction is currently an important research topic.

It is always possible to mix up the role of opium consumption with the known risk of cigarette smoking. This study showed that opium has no protective role in smoker cardiac patients. However, there is still lack of evidence to consider opium as a risk marker for long term outcome in cardiac surgical patients.

This study showed that advanced age, low ejection fraction, lower body mass index, diabetes mellitus, and cerebrovascular accident (CVA) are predictors for long term mortality. High hazard ratio for CVA put an emphasis on the importance of this non cardiac factor in predicting mortality.

This is an interesting manuscript about the effects of opium consumption on all-cause mortality in patients undergoing coronary artery bypass graft surgery.

Manuscript source: Invited manuscript

Specialty type: Cardiac and cardiovascular systems

Country of origin: Iran

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): D

Grade E (Poor): 0

P- Reviewer: Amiya E, Lin GM, Ueda H S- Editor: Gong XM L- Editor: A E- Editor: Wu HL

| 1. | Filardo G, Hamilton C, Grayburn PA, Xu H, Hebeler RF, Hamman B. Established preoperative risk factors do not predict long-term survival in isolated coronary artery bypass grafting patients. Ann Thorac Surg. 2012;93:1943-1948. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Gardner SC, Grunwald GK, Rumsfeld JS, Mackenzie T, Gao D, Perlin JB, McDonald G, Shroyer AL. Risk factors for intermediate-term survival after coronary artery bypass grafting. Ann Thorac Surg. 2001;72:2033-2037. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 50] [Cited by in RCA: 51] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Lok CE, Austin PC, Wang H, Tu JV. Impact of renal insufficiency on short- and long-term outcomes after cardiac surgery. Am Heart J. 2004;148:430-438. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 84] [Cited by in RCA: 92] [Article Influence: 4.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Tran HA, Barnett SD, Hunt SL, Chon A, Ad N. The effect of previous coronary artery stenting on short- and intermediate-term outcome after surgical revascularization in patients with diabetes mellitus. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2009;138:316-323. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Leavitt BJ, Sheppard L, Maloney C, Clough RA, Braxton JH, Charlesworth DC, Weintraub RM, Hernandez F, Olmstead EM, Nugent WC. Effect of diabetes and associated conditions on long-term survival after coronary artery bypass graft surgery. Circulation. 2004;110:II41-II44. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 53] [Cited by in RCA: 58] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | de la Cruz KI, Bakaeen FG, Wang XL, Huh J, LeMaire SA, Coselli JS, Chu D. Hypoalbuminemia and long-term survival after coronary artery bypass: a propensity score analysis. Ann Thorac Surg. 2011;91:671-675. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 56] [Cited by in RCA: 61] [Article Influence: 4.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Hsiung MC, Wei J, Chang CY, Chuang YC, Lee KC, Sue SH, Chou YP, Huang CM, Yin WH, Young MS. O11-01 Long-term survival and prognostic implications of 2130 patients after coronary artery bypass grafting-seven-year follow up. Int J Cardiol. 2004;97:S37-S38. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | van Straten AH, Soliman Hamad MA, van Zundert AA, Martens EJ, Schönberger JP, de Wolf AM. Preoperative renal function as a predictor of survival after coronary artery bypass grafting: comparison with a matched general population. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2009;138:971-976. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Shirani S, Hosseini S. The prevalence of coronary artery disease according to Rose Questionnaire and ECG: Isfahan Healthy Heart Program (IHHP). ARYA Journal. 2006;2:70-74. |

| 10. | Najafi M, Sheikhvatan M, Ataie-Jafari A. Effects of opium use among coronary artery disease patients in Iran. Subst Use Misuse. 2010;45:2579-2581. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Najafi M, Sheikhvatan M. Does analgesic effect of opium hamper the adverse effects of severe coronary artery disease on quality of life in addicted patients? Anesth Pain Med. 2012;2:22-27. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Schultz JE, Gross GJ. Opioids and cardioprotection. Pharmacol Ther. 2001;89:123-137. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 152] [Cited by in RCA: 158] [Article Influence: 6.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Masoomi M, Ramezani MA, Karimzadeh H. The relationship of opium addiction with coronary artery disease. Int J Prev Med. 2010;1:182-186. [PubMed] |

| 14. | Sadeghian S, Karimi A, Dowlatshahi S, Ahmadi SH, Davoodi S, Marzban M, Movahedi N, Abbasi K, Tazik M, Fathollahi MS. The association of opium dependence and postoperative complications following coronary artery bypass graft surgery: a propensity-matched study. J Opioid Manag. 2009;5:365-372. [PubMed] |

| 15. | Safaii N, Kazemi B. Effect of opium use on short-term outcome in patients undergoing coronary artery bypass surgery. Gen Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2010;58:62-67. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Najafi M, Sheikhvatan M, Mortazavi SH. Do preoperative pulmonary function indices predict morbidity after coronary artery bypass surgery? Ann Card Anaesth. 2015;18:293-298. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Karimi A, Ahmadi S, Davoodi S, Marzban M, Movahedi N, Abbasi KE, Salehi Omran A, Shirzad M, Saeed Sadeghian AS, Lotfi-Tokaldany M. First database report on cardiothoracic surgery in Tehran Heart Center. Iran J Public Health. 2008;37:1-8. |

| 18. | Davoodi G, Sadeghian S, Akhondzadeh S, Darvish S, Alidoosti M, Amirzadegan A. Comparison of specifications, short term outcome and prognosis of acute myocardial infarction in opium dependent patients and nondependents. J Tehran Heart Cent. 2006;1:48-53. |

| 19. | De Maria R, Mazzoni M, Parolini M, Gregori D, Bortone F, Arena V, Parodi O. Predictive value of EuroSCORE on long term outcome in cardiac surgery patients: a single institution study. Heart. 2005;91:779-784. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 49] [Cited by in RCA: 47] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Peng E, Sarkar PK. Training the novice to become cardiac surgeon: does the “early learning curve” training compromise surgical outcomes? Gen Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2014;62:149-156. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Yoo JS, Kim JB, Jung SH, Choo SJ, Chung CH, Lee JW. Coronary artery bypass grafting in patients with left ventricular dysfunction: predictors of long-term survival and impact of surgical strategies. Int J Cardiol. 2013;168:5316-5322. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Dunning J, Waller JR, Smith B, Pitts S, Kendall SW, Khan K. Coronary artery bypass grafting is associated with excellent long-term survival and quality of life: a prospective cohort study. Ann Thorac Surg. 2008;85:1988-1993. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Marcheix B, Vanden Eynden F, Demers P, Bouchard D, Cartier R. Influence of diabetes mellitus on long-term survival in systematic off-pump coronary artery bypass surgery. Ann Thorac Surg. 2008;86:1181-1188. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Barsness GW, Peterson ED, Ohman EM, Nelson CL, DeLong ER, Reves JG, Smith PK, Anderson RD, Jones RH, Mark DB. Relationship between diabetes mellitus and long-term survival after coronary bypass and angioplasty. Circulation. 1997;96:2551-2556. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 166] [Cited by in RCA: 166] [Article Influence: 5.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Gruberg L, Mercado N, Milo S, Boersma E, Disco C, van Es GA, Lemos PA, Ben Tzvi M, Wijns W, Unger F. Impact of body mass index on the outcome of patients with multivessel disease randomized to either coronary artery bypass grafting or stenting in the ARTS trial: The obesity paradox II? Am J Cardiol. 2005;95:439-444. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 90] [Cited by in RCA: 98] [Article Influence: 4.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Del Prete JC, Bakaeen FG, Dao TK, Huh J, LeMaire SA, Coselli JS, Chu D. The impact of obesity on long-term survival after coronary artery bypass grafting. J Surg Res. 2010;163:7-11. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Oreopoulos A, Padwal R, Norris CM, Mullen JC, Pretorius V, Kalantar-Zadeh K. Effect of obesity on short- and long-term mortality postcoronary revascularization: a meta-analysis. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2008;16:442-450. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 185] [Cited by in RCA: 230] [Article Influence: 13.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Lin GM, Li YH, Lin CL, Wang JH, Han CL. Relation of body mass index to mortality among Asian patients with obstructive coronary artery disease during a 10-year follow-up: a report from the ET-CHD registry. Int J Cardiol. 2013;168:616-620. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Masoudkabir F, Sarrafzadegan N, Eisenberg MJ. Effects of opium consumption on cardiometabolic diseases. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2013;10:733-740. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 49] [Article Influence: 4.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Khademi H, Malekzadeh R, Pourshams A, Jafari E, Salahi R, Semnani S, Abaie B, Islami F, Nasseri-Moghaddam S, Etemadi A. Opium use and mortality in Golestan Cohort Study: prospective cohort study of 50,000 adults in Iran. BMJ. 2012;344:e2502. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 110] [Cited by in RCA: 126] [Article Influence: 9.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Najafi M. Opium and the heart: Common challenges in investigation. J Tehran Heart Cent. 2010;5:113-115. |