Published online Jun 26, 2015. doi: 10.4330/wjc.v7.i6.367

Peer-review started: October 30, 2014

First decision: November 14, 2014

Revised: January 16, 2015

Accepted: April 1, 2015

Article in press: April 7, 2015

Published online: June 26, 2015

Processing time: 238 Days and 6.1 Hours

We present a case of a 71-year-old male who had chest symptoms at rest and during effort. He had felt chest oppression during effort for 1 year, and his chest symptoms had recently worsened. One month before admission he felt chest squeezing at rest in the early morning. He presented at our institution to evaluate his chest symptoms. Electrocardiography and echocardiography failed to show any specific changes. Because of the possibility that his chest symptoms were due to myocardial ischemia, he was admitted to our institution for coronary angiography (CAG). An initial CAG showed mild atherosclerotic changes in the proximal segment of the left anterior descending coronary artery (LAD) and mid-segment of the left circumflex coronary artery. Subsequent spasm provocation testing using acetylcholine revealed a bilateral coronary vasospasm, which was relieved after the intracoronary infusion of nitroglycerin. Finally, a CAG showed myocardial bridging (MB) of the mid-distal segments of the LAD. Fractional flow reserve using the intravenous administration of adenosine triphosphate was positive at 0.77, which jumped up to 0.90 through the myocardial bridging segments when the pressure wire was pulled back. Thus, coronary vasospasm and MB might have contributed to his chest symptoms at rest and during effort. Interventional cardiologists should consider the presence of MB as a potential cause of myocardial ischemia.

Core tip: Myocardial bridging (MB), an anomaly in which the myocardium overlies the intramural course of segments of the epicardial coronary arteries, is associated with cardiac events. This may be explained by myocardial ischemia, coronary spasms, and/or mechanical compression of the coronary artery by the MB itself. We encountered a patient with angina pectoris both at rest and during exercise, which was caused by both coronary spasm and MB-induced direct myocardial ischemia. The latter finding was revealed using a pressure wire. MB sometimes causes two vascular characteristics, coronary spasms and direct myocardial ischemia, whose management is quite different.

- Citation: Teragawa H, Fujii Y, Ueda T, Murata D, Nomura S. Case of angina pectoris at rest and during effort due to coronary spasm and myocardial bridging. World J Cardiol 2015; 7(6): 367-372

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1949-8462/full/v7/i6/367.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4330/wjc.v7.i6.367

Myocardial bridging (MB) is an anomaly in which the myocardium overlies the intramural course of segments of the epicardial coronary arteries[1]. The frequency of MB ranges from 5.4% to 85% in autopsy series[2-4] and from 0.5% to 29.4% on coronary angiography[4-10]. It has been accepted that MB might affect the cardiovascular system[1,8,11-13]. In addition, the presence of MB is associated with myocardial infarction[14-17] and sudden cardiac death[18-20]. Myocardial ischemia due to compression of the coronary artery by MB[21,22] and/or coronary spasm at the MB segments[12,23-25] has been considered a major factor responsible for MB-related cardiac events. In this study, we report a case of angina pectoris at both rest and during exercise due to both coronary spasm and MB-related myocardial ischemia, which was documented using a pressure wire.

A 71-year-old male had felt chest oppression on effort, such as when carrying heavy baggage, for 1 year. Recently, his chest symptoms had occurred more frequently. One month before admission he felt chest squeezing at rest in the early morning. He presented at our institution for an evaluation of his chest symptoms in May 2014. Coronary risk factors such as smoking, hypertension, and diabetes mellitus were all absent, although he had a low level of high-density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol. His mother had angina pectoris. He had undergone operations for appendicitis and prostate cancer at the ages of 25 and 69 years, respectively. On medical examination, his height was 1.63 m, his weight was 73 kg, and his body mass index was 27.5. His vital signs were stable with a blood pressure of 110/80 mmHg and a pulse of 59 beats/min. No cardiac murmur or abnormal respiratory sounds in the lungs were detected. Blood examinations revealed elevated levels of creatinine (1.06 mg/dL), uric acid (9.4 mg/dL), and triglycerides (227 mg/dL), and a low level of HDL cholesterol (35 mg/dL). Neither a chest X-P, electrocardiogram, nor echocardiography showed any specific changes. He was admitted to our institution for coronary angiography (CAG) because of the possibility that his chest symptoms were due to myocardial ischemia.

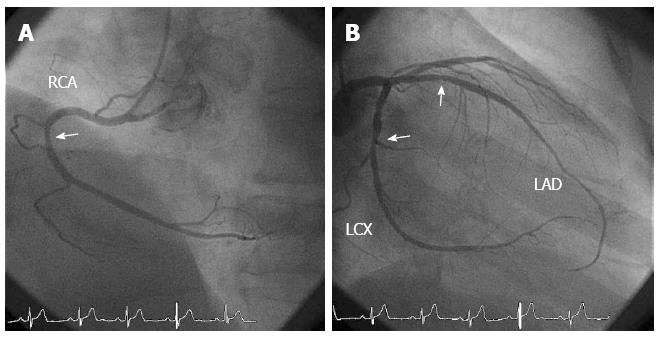

An initial CAG showed mild atherosclerotic changes at the proximal segments of the right coronary artery (RCA), the left anterior descending coronary artery (LAD) and the mid-segment of the left circumflex coronary artery (Figure 1). To clarify the cause of his chest symptoms, we performed spasm provocation testing using acetylcholine (ACh). During the spasm provocation test, a pressure wire (PrimeWire Prestige PLUS, Volcano Therapeutics Inc., Rancho Cordova, CA, USA) was inserted into the distal portion of the RCA and distal portion of the LAD. The ratio of the distal pressure, derived from the pressure wire, to the proximal one, derived from the tip of catheter (Pd/Pa), was continuously monitored.

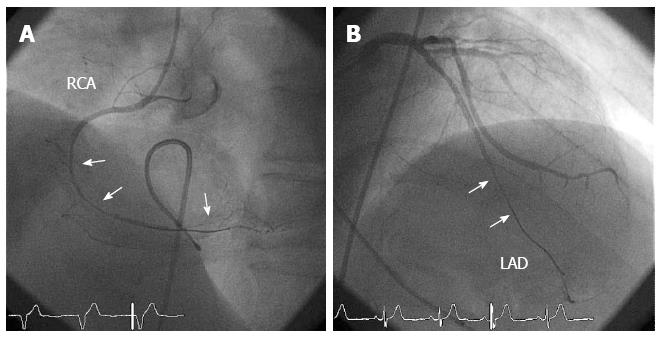

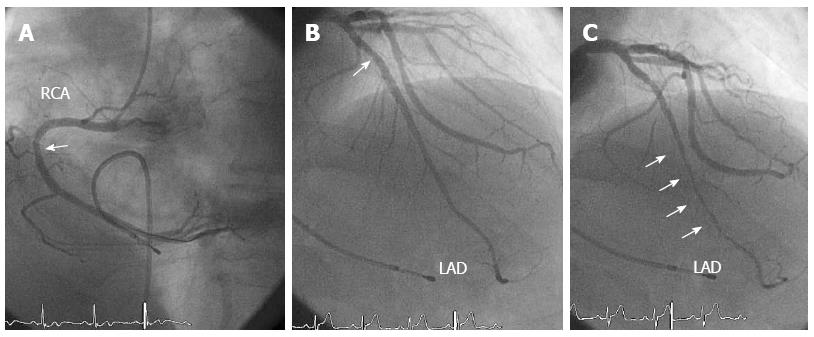

Intracoronary infusion of 50 μg ACh caused a diffuse coronary spasm at the mid-distal portion of the RCA (Figure 2A), which was accompanied by the usual chest symptoms and a reduction in the Pd/Pa from 1.0 to 0.69 at baseline. Because of the prolonged coronary spasm, 600 μg nitroglycerin (NTG) was intracoronarily administered, which relieved the coronary spasm in the RCA (Figure 3A). The subsequent intracoronary infusion of 100 μg ACh in the LCA resulted in no chest symptoms but a diffuse spasm in the mid-distal portion of the LAD (Figure 2B), which was accompanied by a reduction in the Pd/Pa from 0.94 to 0.60 at baseline. The intracoronary infusion of 300 μg NTG relieved the coronary spasm and returned the Pd/Pa to the baseline value of 0.94. A final CAG revealed an MB of the mid-distal segments of the LAD (Figures 3B and C). The length and percent systolic narrowing of the MB segment was 38 mm and 78%, respectively. The fractional flow reserve (FFR) of the LAD, which was assessed using a pressure wire and the intravenous administration of 160 μg/min per kilogram adenosine triphosphate (ATP), was positive at 0.77 from 0.94 at baseline (Figure 4A). It then jumped to 0.90 through the MB segments when the pressure wire was pulled back (Figure 4B). Therefore, multi-vessel coronary spasms and a myocardial bridge may contribute to his chest symptoms at rest and during effort. The following day he was discharged and prescribed diltiazem (300 mg/d). Since then, he has been taking 300 mg/d diltiazem and 15 mg/d nicorandil and his symptoms have been controlled in the outpatient clinic.

In this study, we present a case of angina pectoris both during exercise and at rest. These symptoms were due to bilateral coronary spasms and MB-related myocardial ischemia, which was identified using a pressure wire.

Several reports have described MB-related myocardial infarction[14-17] and sudden cardiac death[18-20]. Myocardial ischemia has been suggested to be the main cause of MB-related cardiac events due to mechanical compression of the coronary artery by the MB[21,22] and/or coronary spasm at the MB segments[12,23-25]. It is possible that coronary spasms frequently occur at MB segments because of endothelial dysfunction and/or vascular dysfunction of the coronary artery at MB segments[11,12]. Although the current case had multivessel coronary spasms, the segment of the LAD that underwent coronary spasm was the same as the MB segment, which is consistent with an MB-related coronary spasm. This suggests that cardiologists should consider the possibility of coronary spasm in patients with chest pain and MB on coronary angiograms. Several methods have been used to assess MB-related myocardial ischemia due to mechanical compression of the coronary artery by MB, such as pharmacological stress echocardiography[26], stress myocardial perfusion imaging[27], intracoronary blood flow velocity measurements[21,26], and intracoronary pressure measurements[1,21,26,28]. In the current case, we assessed intracoronary pressure using a pressure wire because this technique has a reliable cutoff value[29] and can be used conveniently in the clinical setting.

Regarding the relationship between intracoronary pressure and MB, reports describing the pressure gradient within the MB segment vary. For example, it has been reported that a pressure gradient within the MB segment is present even at baseline[21], only during pharmacological stress[1,26,28], only within the MB segment[26], or both within and beneath MB[1,21,28]. These different results may have been due to differences in the severity and degree of the MB itself as well as differences in the methods used to measure intracoronary pressure. According to the current results, where Pd/Pa was 0.94 and FFR was 0.77 at baseline and the Pd/Pa increased to 0.90 through the MB segments, a pressure gradient was present only during pharmacological stress and within and beneath the MB.

ATP is used frequently to measure FFR in the clinical setting during the assessment of MB. However, it has been reported that dobutamine is more useful as the stress agent during the assessment of MB[1,26,28] because it causes a more severe and longer compression within the MB[28]. Assessing the FFR of the vessel containing the MB can be challenging[30] because atherosclerotic changes often occur proximal to the MB[1], which may reduce FFR. The present case had a minor atherosclerotic lesion proximal to the MB; however, the FFR increased to 0.90 just proximal to the MB when the pressure wire was pulled back. Therefore, in cases with MB and proximal atherosclerotic lesions, assessing FFR using the combination of the pullback method may be more useful.

β-blockers are the mainstay of treatment for symptomatic patients with MB[1]. However, as shown in the present case, coronary spasms sometimes occur in patients with MB, particularly in the MB segments[12]. In general, monotherapy using β-blockers is prohibited in patients with coronary spasms[31]. Furthermore, the use of NTG, which is very effective for relieving coronary spasms, may exacerbate the systolic narrowing of the MB segments[32]. Therefore, it is important to ascertain the presence of coronary spasms in patients with MB. Furthermore, in cases with both MB and coronary spasms, calcium-channel blockers (CCB) or CCB plus β-blockers may be useful. Patients with coronary spasms and MB should be monitored carefully when these drugs are administered. In the present case, CCB with diltiazem plus nicorandil was used to treat the coronary spasm, which was the main pathology in the present case. When chest symptoms are present during exercise the use of β-blockers should be considered. It was reported that percutaneous coronary intervention is useful to relieve chest symptoms in patients with MB[1,22,30,33]; however, it was also reported that the incidence restenosis is relatively high[1,30]. Therefore, pharmacological treatment should be used even in patients with MB and a significantly reduced FFR.

In conclusion, coronary spasms sometimes consolidate in patients with MB, and the presence of coronary spasms should be assessed in such patients. In addition, intracoronary pressure measurements using a pressure wire may be useful to assess the severity of MB. Interventional cardiologists should keep these concepts in mind.

A 71-year-old male presented chest oppression during effort and chest squeezing at rest.

Angina pectoris due to coronary spasm and myocardial bridging.

Angina pectoris due to significant coronary stenosis, pulmonary thromboembolism.

Elevated levels of creatinine (1.06 mg/dL), uric acid (9.4 mg/dL), and triglycerides (227 mg/dL), and a low level of HDL cholesterol (35 mg/dL).

Coronary angiography showed mild atherosclerotic changes. Spasm provocation testing using acetylcholine showed multi-vessel coronary spasms. Coronary angiography after an intracoronary infusion of nitroglycerin showed myocardial bridging of the left anterior descending coronary artery. The fractional flow reserve using adenosine triphosphate was positive at 0.77.

The patient was treated with 300 mg/d diltiazem and 15 mg/d nicorandil.

Angina pectoris due to coronary spasms or myocardial bridging is well-known, however, little has been reported regarding angina pectoris at rest and during effort due to both coronary spasms and myocardial bridging.

Myocardial bridging is an anomaly in which the myocardium overlies the intramural course of segments of the epicardial coronary arteries and is associated with cardiac events.

This report presents a case of angina pectoris due to coronary spasm and myocardial bridging. Coronary spasms sometimes consolidate in patients with myocardial bridging, and the presence of coronary spasms should be assessed in such patients. In addition, intracoronary pressure measurements using a pressure wire may be useful to assess the severity of myocardial bridging.

This is an interesting case. The case is well presented and the text well written.

P- Reviewer: Mehta Y, Nikus K, Paraskevas K, Rauch B S- Editor: Song XX L- Editor: A E- Editor: Zhang DN

| 1. | Corban MT, Hung OY, Eshtehardi P, Rasoul-Arzrumly E, McDaniel M, Mekonnen G, Timmins LH, Lutz J, Guyton RA, Samady H. Myocardial bridging: contemporary understanding of pathophysiology with implications for diagnostic and therapeutic strategies. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014;63:2346-2355. |

| 2. | Burnsides C, Edwards JC, Lansing AI, Swarm RL. Arteriosclerosis in the intramural and extramural portions of coronary arteries in the human heart. Circulation. 1956;13:235-241. |

| 3. | Polacek P, Kralove H. Relation of myocardial bridges and loops on the coronary arteries to coronary occulsions. Am Heart J. 1961;61:44-52. |

| 4. | Angelini P, Trivellato M, Donis J, Leachman RD. Myocardial bridges: a review. Prog Cardiovasc Dis. 1983;26:75-88. |

| 5. | Noble J, Bourassa MG, Petitclerc R, Dyrda I. Myocardial bridging and milking effect of the left anterior descending coronary artery: normal variant or obstruction? Am J Cardiol. 1976;37:993-999. |

| 6. | Ishimori T, Raizner AE, Chahine RA, Awdeh M, Luchi RJ. Myocardial bridges in man: clinical correlations and angiographic accentuation with nitroglycerin. Cathet Cardiovasc Diagn. 1977;3:59-65. |

| 7. | Greenspan M, Iskandrian AS, Catherwood E, Kimbiris D, Bemis CE, Segal BL. Myocardial bridging of the left anterior descending artery: evaluation using exercise thallium-201 myocardial scintigraphy. Cathet Cardiovasc Diagn. 1980;6:173-180. |

| 8. | Rossi L, Dander B, Nidasio GP, Arbustini E, Paris B, Vassanelli C, Buonanno C, Poppi A. Myocardial bridges and ischemic heart disease. Eur Heart J. 1980;1:239-245. |

| 10. | Kramer JR, Kitazume H, Proudfit WL, Sones FM. Clinical significance of isolated coronary bridges: benign and frequent condition involving the left anterior descending artery. Am Heart J. 1982;103:283-288. |

| 11. | Shiode N, Kato M, Teragawa H, Yamada T, Hirao H, Nomura K, Sasaki N, Yamagata T, Matsuura H, Kajiyama G. Vasomotility and nitric oxide bioactivity of the bridging segments of the left anterior descending coronary artery. Am J Cardiol. 1998;81:341-343. |

| 12. | Teragawa H, Fukuda Y, Matsuda K, Hirao H, Higashi Y, Yamagata T, Oshima T, Matsuura H, Chayama K. Myocardial bridging increases the risk of coronary spasm. Clin Cardiol. 2003;26:377-383. |

| 13. | Hayashi T, Ishikawa K. Myocardial bridge: harmless or harmful. Intern Med. 2004;43:1097-1098. |

| 14. | Baldassarre S, Unger P, Renard M. Acute myocardial infarction and myocardial bridging: a case report. Acta Cardiol. 1996;51:461-465. |

| 15. | Agirbasli M, Martin GS, Stout JB, Jennings HS, Lea JW, Dixon JH. Myocardial bridge as a cause of thrombus formation and myocardial infarction in a young athlete. Clin Cardiol. 1997;20:1032-1036. |

| 16. | Tauth J, Sullebarger T. Myocardial infarction associated with myocardial bridging: case history and review of the literature. Cathet Cardiovasc Diagn. 1997;40:364-367. |

| 17. | Kurisu S, Inoue I, Kawagoe T, Ishihara M, Shimatani Y, Mitsuba N, Hata T, Nakama Y, Kisaka T, Kijima Y. Acute myocardial infarction associated with myocardial bridging in a young adult. Intern Med. 2004;43:1157-1161. |

| 18. | Bestetti RB, Costa RS, Zucolotto S, Oliveira JS. Fatal outcome associated with autopsy proven myocardial bridging of the left anterior descending coronary artery. Eur Heart J. 1989;10:573-576. |

| 19. | Cutler D, Wallace JM. Myocardial bridging in a young patient with sudden death. Clin Cardiol. 1997;20:581-583. |

| 20. | Yamaguchi M, Tangkawattana P, Hamlin RL. Myocardial bridging as a factor in heart disorders: critical review and hypothesis. Acta Anat (Basel). 1996;157:248-260. |

| 21. | Ge J, Erbel R, Görge G, Haude M, Meyer J. High wall shear stress proximal to myocardial bridging and atherosclerosis: intracoronary ultrasound and pressure measurements. Br Heart J. 1995;73:462-465. |

| 22. | Kurtoglu N, Mutlu B, Soydinc S, Tanalp C, Izgi A, Dagdelen S, Bakkal RB, Dindar I. Normalization of coronary fractional flow reserve with successful intracoronary stent placement to a myocardial bridge. J Interv Cardiol. 2004;17:33-36. |

| 23. | Ciampricotti R, el Gamal M. Vasospastic coronary occlusion associated with a myocardial bridge. Cathet Cardiovasc Diagn. 1988;14:118-120. |

| 24. | Munakata K, Sato N, Sasaki Y, Yasutake M, Kusama Y, Takayama M, Kishida H, Hayakawa H. Two cases of variant form angina pectoris associated with myocardial bridge--a possible relationship among coronary vasospasm, atherosclerosis and myocardial bridge. Jpn Circ J. 1992;56:1248-1252. |

| 25. | Kodama K, Morioka N, Hara Y, Shigematsu Y, Hamada M, Hiwada K. Coronary vasospasm at the site of myocardial bridge--report of two cases. Angiology. 1998;49:659-663. |

| 26. | Lin S, Tremmel JA, Yamada R, Rogers IS, Yong CM, Turcott R, McConnell MV, Dash R, Schnittger I. A novel stress echocardiography pattern for myocardial bridge with invasive structural and hemodynamic correlation. J Am Heart Assoc. 2013;2:e000097. |

| 27. | Gawor R, Kuśmierek J, Płachcińska A, Bieńkiewicz M, Drożdż J, Piotrowski G, Chiżyński K. Myocardial perfusion GSPECT imaging in patients with myocardial bridging. J Nucl Cardiol. 2011;18:1059-1065. |

| 28. | Escaned J, Cortés J, Flores A, Goicolea J, Alfonso F, Hernández R, Fernández-Ortiz A, Sabaté M, Bañuelos C, Macaya C. Importance of diastolic fractional flow reserve and dobutamine challenge in physiologic assessment of myocardial bridging. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2003;42:226-233. |

| 29. | Tonino PA, De Bruyne B, Pijls NH, Siebert U, Ikeno F, van’ t Veer M, Klauss V, Manoharan G, Engstrøm T, Oldroyd KG. Fractional flow reserve versus angiography for guiding percutaneous coronary intervention. N Engl J Med. 2009;360:213-224. |

| 30. | Singh IM, Subbarao RA, Sadanandan S. Limitation of fractional flow reserve in evaluating coronary artery myocardial bridge. J Invasive Cardiol. 2008;20:E161-E166. |

| 31. | JCS Joint Working Group. Guidelines for diagnosis and treatment of patients with vasospastic angina (coronary spastic angina) (JCS 2008): digest version. Circ J. 2010;74:1745-1762. |

| 32. | Hongo Y, Tada H, Ito K, Yasumura Y, Miyatake K, Yamagishi M. Augmentation of vessel squeezing at coronary-myocardial bridge by nitroglycerin: study by quantitative coronary angiography and intravascular ultrasound. Am Heart J. 1999;138:345-350. |