Published online Jun 26, 2015. doi: 10.4330/wjc.v7.i6.351

Peer-review started: January 10, 2015

First decision: January 20, 2015

Revised: February 19, 2015

Accepted: March 30, 2015

Article in press: April 2, 2015

Published online: June 26, 2015

Processing time: 166 Days and 14.4 Hours

Saphenous vein grafts (SVG) pseudoaneurysms, especially giant ones, are rare and occur as a late complication of coronary artery bypass grafting. This condition affects both genders and typically occurs within the sixth decade of life. The clinical presentation ranges from an asymptomatic incidental finding on imaging studies to new onset angina, dyspnea, myocardial infarction or symptoms related to compression of neighboring structures. An 82-year-old woman presented with acute onset back pain, dyspnea and was noted to have significantly engorged neck veins. In the emergency department, a chest computed tomographic angiogram with intravenous contrast revealed a ruptured giant bilobed SVG pseudoaneurysm to the right posterior descending artery (RPDA). This imaging modality also demonstrated compression of the superior vena cava (SVC) by the SVG pseudoaneurysm. Coronary angiogram with bypass study was performed to establish the patency of this graft. Endovascular coiling and embolization of the SVG to RPDA was initially considered but disfavored after the coronary angiogram revealed preserved flow from the graft to this arterial branch. After reviewing the angiogram films, a surgical strategy was favored over a percutaneous intervention with a Nitinol self-expanding stent since the latter would have not addressed the superior vena cava compression caused by the giant pseudoaneurysm. Intraoperative transesophageal echocardiogram demonstrated SVC compression by the giant pseudoaneurysm cranial lobe. Our patient underwent surgical ligation and excision of the giant pseudoaneurysm and the RPDA was regrafted successfully. In summary, saphenous vein grafts pseudoaneurysms can be life-threatening and its therapy should be guided based on the presence of mechanical complications, the patency of the affected vein graft and the involved myocardial territory viability.

Core tip: Saphenous vein grafts (SVG) pseudoaneurysms, especially giant ones, are rare and occur as a late complication of coronary artery bypass grafting. Although unusual, superior vena cava (SVC) syndrome has been reported as a complication of saphenous vein graft pseudoaneurysms causing compression of the SVC. Here we report a case of such condition illustrated with state-of-the-art multi-modality images which were critical for the planning of the most appropriate treatment strategy. SVG pseudoaneurysms can be life-threatening and their therapy should be guided based on the presence of mechanical complications, the patency of the affected vein graft and the involved myocardial territory viability.

- Citation: Vargas-Estrada A, Edwards D, Bashir M, Rossen J, Zahr F. Giant saphenous vein graft pseudoaneurysm to right posterior descending artery presenting with superior vena cava syndrome. World J Cardiol 2015; 7(6): 351-356

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1949-8462/full/v7/i6/351.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4330/wjc.v7.i6.351

Coronary saphenous vein graft pseudoaneurysms are rare complications of coronary artery bypass grafting, occurring several years after the initial procedure. Although very unusual, superior vena cava obstruction has been reported as a complication of a rupture of a coronary artery bypass vein graft[1]. It is uncommon to encounter such patients and the optimal treatment remains uncertain. The improvement of percutaneous interventions and the development of covered and Nitinol self-expanding stents have become an attractive option to spare these subjects from a repeat thoracotomy, however this is not always feasible. To our knowledge, there have been very few similar cases reported, we believe this to be the first reported case of such condition illustrated with state-of-the-art multi-modality imaging.

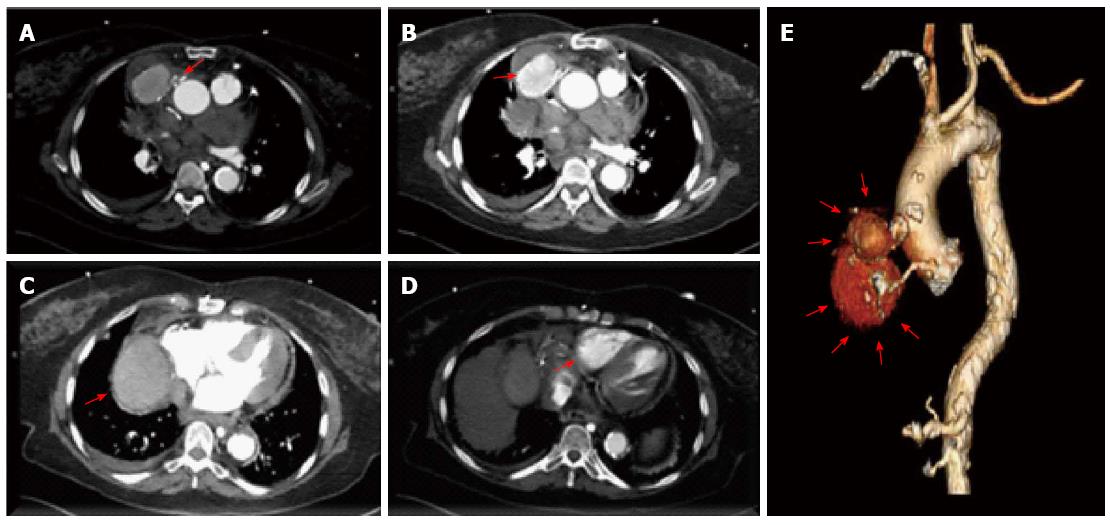

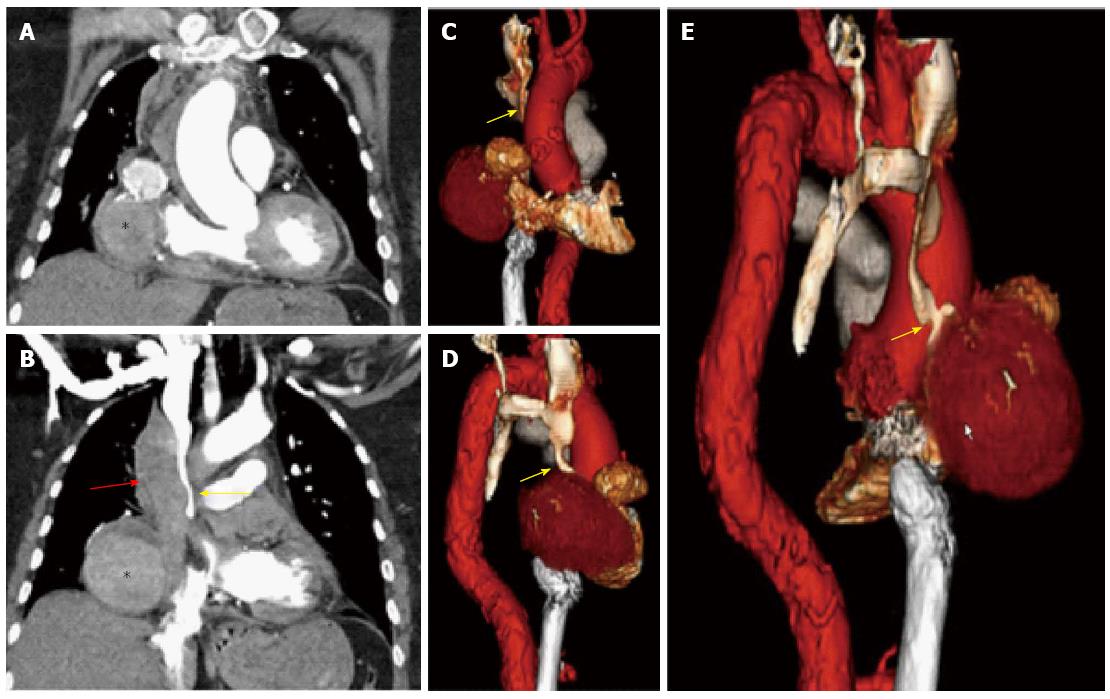

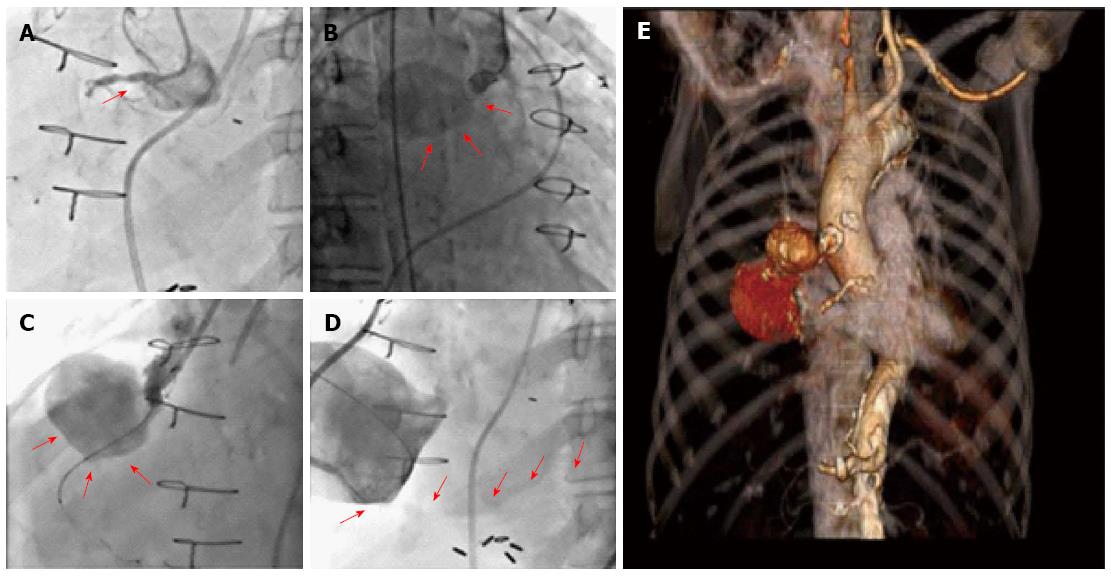

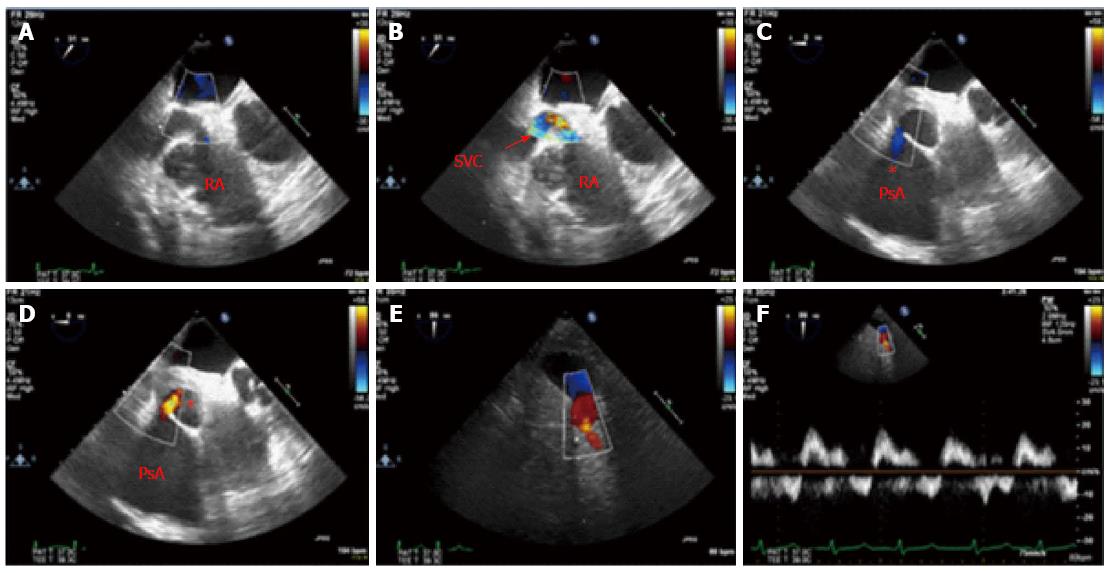

An 82-year-old woman presented to the hospital with complaints of acute onset back pain, dyspnea for twelve hours and significantly engorged neck veins. She had undergone 3-vessel coronary artery bypass graft surgery in 1993. At the time of her coronary artery bypass operation, the left internal mammary artery (LIMA) was used to graft the first diagonal branch. Separate saphenous vein grafts were placed to the left anterior descending artery (LAD) and right posterior descending artery (RPDA). It is unknown to us the reasons for LIMA to diagonal branch anastomosis instead of arterial bypass to LAD which in turn received a venous graft. On her arrival to the emergency department, an electrocardiogram showed sinus rhythm and no ischemic changes. Her cardiac enzymes were negative. Computed tomography with IV contrast of the patient’s chest ruled out pulmonary embolism and aortic dissection. Tomographic and 3D reconstruction views identified a ruptured giant bilobed SVG pseudoaneurysm to RPDA causing mass effect on the superior vena cava and right-sided cardiac chambers (Figures 1 and 2). The cranial lobe of the pseudoaneurysm measured 4.7 cm × 5.4 cm and the caudal lobe measured 8.0 cm × 7.0 cm in its larger diameter and demonstrated mural thrombosis. Coronary angiography demonstrated a giant pseudoaneurysm of the SVG with patent flow to the right posterior descending artery (Figure 3). Coiling and embolization of the SVG to RPDA was initially considered but disfavored since the coronary angiogram revealed preserved flow from the graft to RPDA branch. Also a percutaneous intervention with a covered vs a Nitinol self-expanding stent to the ruptured SVG was contemplated but ultimately surgical intervention was decided since the former strategy would have not addressed the superior vena cava compression caused by the giant pseudoaneurysm. Intraoperative echocardiography (Figure 4) showed SVC compression by the giant pseudoaneurysm cranial lobe. At surgery, the giant SVG pseudoaneurysm was ligated, excised and the RPDA was regrafted. The patient recovered uneventfully and was discharged on postoperative day 20. After completing her post-surgical rehabilitation, she returned to our clinic six weeks later, asymptomatic and in stable condition.

Aneurysmal dilatation of aortocoronary saphenous vein grafts (SVG), first described by Riahi et al[2] in 1975 remains a rare yet widely reported phenomenon. This condition is secondary to true aneurysm or pseudoaneurysm, with the former being more common. SVC syndrome is caused by obstruction of blood flow through the superior vena cava due to thrombosis or extrinsic compression. It is a medical emergency and most often manifests in patients with a malignant process within the thorax (particularly lung adenocarcinoma), however as many as 40% of cases are attributable to nonmalignant causes. The first case of ruptured SVG pseudoaneurysm presenting with SVC syndrome was reported by Rosin and colleagues[3] in 1989. Kavanagh et al[4] in 2004 reported the first case in which CT findings of this condition were described. We presented a case of a giant saphenous vein graft pseudoaneurysm to right posterior descending artery in a patient presenting with superior vena cava (SVC) syndrome. The precise incidence of SVG aneurysms remains difficult to ascertain and more so for SVG pseudoaneurysms. In one case series, an incidence of 0.07% was estimated from a review of 5500 grafts at a single institution[5]. This condition occurs in both genders but predominates in men (87% of reported cases on average within the sixth decade of life). Postulated mechanisms for SVGs aneurysmal dilatation include atherosclerotic degeneration of the graft, vessel wall ischemia secondary to disruption of the vasa vasorum during the harvesting and grafting process, graft endothelial dysfunction and changes in medial smooth muscle cell orientation in the vicinity of valve sites[6]. The clinical presentation is somewhat variable and ranges from an asymptomatic incidental finding on chest X-ray (12%-47%) to new onset angina (46.4%), shortness of breath (12.9%), myocardial infarction (7.7%), hemoptysis (4.8%), hemothorax, or symptoms related to compression of neighboring structures, as well as shock (3.8%) or death[7]. SVGs aneurysms predominate in the right coronary distribution thus compression of right-sided cardiac structures is more common. Our patient presented with significantly distended neck veins secondary to compression of the superior vena cava by the giant SVG pseudoaneurysm to RPDA (Figure 2). The mechanical complications include right atrial compression (11.5% of cases), right ventricular compression (7.2%) and fistula formation (7.7%)[8]. The most feared complication is aneurysm rupture which has been reported as a presenting feature in only a minority of cases. Although frequently identifiable on chest X-ray or echocardiography, coronary angiography is required to evaluate the patency of the coronary arteries and bypass grafts. Confirmation of the size of the aneurysm or pseudoaneurysm and the relationship to the surrounding structures is best achieved with CT angiography or MRA. Different treatments options exist and are applied according to the anatomy of the pseudoaneurysm, mechanical complication and the patency of the affected vein graft. Repeat coronary artery bypass grafting with aneurysmal ligation or excision is the classic approach[9]. In cases in which the affected graft remains patent despite the aneurysmal dilation and in non-surgical candidates for repeat sternotomy, percutaneous management with a covered stent should be considered. In patients in whom preservation of myocardial blood supply is not a concern or non-viable myocardium has been demonstrated, the aneurysmal neck can be occluded by Amplatzer vascular plugs[9] or the aneurysm can be thrombosed by endovascular coiling[10]. Although large-bore Nitinol stents are highly effective for superior vena cava syndrome, in our case it was decided to proceed with re-thoracotomy and excision of the graft pseudoaneurysm after rupture was demonstrated by CT imaging and coronary angiography. The SVC syndrome resolved with the surgical excision of the ruptured SVG pseudoaneurysm. The optimal treatment for this condition remains an area of uncertainty with available data based on case reports and small case series and certainly depends upon the clinical scenario and should be made by a multidisciplinary cardiac team.

An 82-year-old woman presented with acute onset back pain, dyspnea and engorged neck veins.

Dyspnea of twelve hours duration and engorged neck veins, later were found to be caused by superior vena cava syndrome from superior vena cava (SVC) compression by a giant saphenous vein grafts (SVG) pseudoaneurysm.

Any cause for acute onset back pain and dyspnea such as acute coronary syndrome, pulmonary embolism, aortic dissection, etc.

Lab tests result including cardiac enzymes were unremarkable.

Multi-imaging modalities including computed tomography chest angiogram, coronary angiogram and TEE revealed a giant bilobed SVG pseudoaneurysm to the right posterior descending artery causing compression of the superior vena cava leading to SVC syndrome.

Surgical ligation and excision of the SVG pseudoaneurysm with regrafting of right posterior descending artery.

Saphenous vein graft pseudoaneurysms can present as a late complication following coronary artery bypass grafting. Although most frequently asymptomatic and found incidentally by imaging modalities, the authors should consider this condition in the differential diagnoses for acute coronary syndrome and as a possible explanation of SVC syndrome in patients with prior coronary artery grafting. Different treatments options exist and are applied according to the anatomy of the pseudoaneurysm, mechanical complication and the patency of the affected vein graft.

This is an interesting report for clinical practice.

P- Reviewer: Ghanem A, Kettering K, Lazzeri C, Sakabe K, Vermeersch P S- Editor: Qi Y L- Editor: A E- Editor: Zhang DN

| 1. | Le Breton H, Pavin D, Langanay T, Roland Y, Leclercq C, Beliard JM, Bedossa M, Rioux C, Pony JC. Aneurysms and pseudoaneurysms of saphenous vein coronary artery bypass grafts. Heart. 1998;79:505-508. |

| 2. | Riahi M, Vasu CM, Tomatis LA, Schlosser RJ, Zimmerman G. Aneurysm of saphenous vein bypass graft to coronary artery. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1975;70:358-359. |

| 3. | Rosin MD, Ridley PD, Maxwell PH. Rupture of a pseudoaneurysm of a saphenous vein coronary arterial bypass graft presenting with superior caval venous obstruction. Int J Cardiol. 1989;25:121-123. |

| 4. | Kavanagh EC, Hargaden G, Flanagan F, Murray JG. CT of a ruptured vein graft pseudoaneurysm: an unusual cause of superior vena cava obstruction. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2004;183:1239-1240. |

| 5. | Dieter RS, Patel AK, Yandow D, Pacanowski JP, Bhattacharya A, Gimelli G, Kosolcharoen P, Russell D. Conservative vs. invasive treatment of aortocoronary saphenous vein graft aneurysms: Treatment algorithm based upon a large series. Cardiovasc Surg. 2003;11:507-513. |

| 6. | Vlodaver Z, Edwards JE. Pathologic changes in aortic-coronary arterial saphenous vein grafts. Circulation. 1971;44:719-728. |

| 7. | Ramirez FD, Hibbert B, Simard T, Pourdjabbar A, Wilson KR, Hibbert R, Kazmi M, Hawken S, Ruel M, Labinaz M. Natural history and management of aortocoronary saphenous vein graft aneurysms: a systematic review of published cases. Circulation. 2012;126:2248-2256. |

| 8. | Topaz O. Giant aneurysms of saphenous vein grafts: management dilemmas and treatment options. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2006;67:617-618. |

| 9. | Mylonas I, Sakata Y, Salinger MH, Feldman T. Successful closure of a giant true saphenous vein graft aneurysm using the Amplatzer vascular plug. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2006;67:611-616. |

| 10. | Lacombe P, Rocha P, Qanadli SD, Guichoux F, Pillière R, El Hajjam M, Foudali A, Bourdarias JP, Dubourg O. Aneurysms of saphenous vein grafts as late complication of coronary artery bypass surgery: successful exclusion by percutaneous transcatheter embolization. Eur Radiol. 2002;12:915-919. |