Published online Mar 26, 2015. doi: 10.4330/wjc.v7.i3.161

Peer-review started: September 5, 2014

First decision: November 3, 2014

Revised: December 2, 2014

Accepted: December 16, 2014

Article in press: December 17, 2014

Published online: March 26, 2015

Processing time: 189 Days and 14.5 Hours

We report on an 83-year-old male with traumatic brain injury after syncope with a fall in the morning. He had a history of seizures, coronary artery disease and paroxysmal atrial fibrillation (AF). No medical cause for seizures and syncope was determined. During rehabilitation, the patient still complained of seizures, and also reported sleepiness and snoring. Sleep apnea diagnostics revealed obstructive sleep apnea (SA) with an apnea-hypopnoea index of 35/h, and sudden onset of tachycardia with variations of heart rate based on paroxysmal atrial fibrillation. Additional tests showed nocturnal AF which spontaneously converted to sinus rhythm mid-morning with an arrest of 5 s (sick sinus syndrome) and seizures. A DDD-pacer was implanted and no further seizures occurred. SA therapy with nasal continuous positive airway pressure was refused by the patient. Our findings suggests that screening for SA may offer the possibility to reveal causes of syncope and may introduce additional therapeutic options as arrhythmia and SA often occur together which in turn might be responsible for trauma due to syncope episodes.

Core tip: Arrhythmias and sleep apnea should be considered as relevant factors resulting in syncope and trauma in the elderly. This case report applies screening for sleep apnea to detect arrhythmia as a common cause of syncope. Screening for sleep apnea may offer the possibility of additional therapeutic options and diagnostic in trauma and syncope after performing standard diagnostics.

- Citation: Skobel E, Bell A, Nguyen DQ, Woehrle H, Dreher M. Trauma and syncope-evidence for further sleep study? A case report. World J Cardiol 2015; 7(3): 161-166

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1949-8462/full/v7/i3/161.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4330/wjc.v7.i3.161

Sleep apnea (SA) has been shown to be an independent risk factor for cardiovascular diseases[1-4]. Obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) is the most prevalent type of SA. It is defined as repetitive episodes of partial or complete cessation of airflow in the upper airways during sleep. The number of people in the United States estimated to be affected by OSA is 3%-7%[5,6] and, according to US National Commission of Sleep Disorders Research, OSA contributes to 38000 cardiovascular deaths annually[7]. In Europe, a Spanish study reported that 7% of women and 15% of men aged 30-70 years had OSA, defined as an apnea-hypopnoea index (AHI) of ≥ 15/h[8].

Patients with OSA typically present with symptoms such as disruptive snoring, witnessed apneas or gasping, excessive daytime sleepiness, morning headache, sleep disturbance and cognitive dysfunction[9,10]. OSA is associated with higher prevalence of diabetes and hypertension[11,12], coronary artery disease and myocardial infarction[13], heart failure[14] and arrhythmias such as bradycardia or atrial fibrillation or flutter (AF)[15]. Traumatic brain injury (TBI) is often associated with SA and sleep disturbances[16,17]. Although the incidence of arrhythmia in the presence of SA is high[15,18,19], the influence of SA on traumatic loss of consciousness (syncope) and TBI have rarely been evaluated[20-22].

Syncope is the most common cause of TBI in the elderly and it often has an underlying cardiovascular aetiology (e.g., bradycardia, tachycardia, myocardial infarction or valvular disease)[23]. The incidence of syncope is 5-11 events per 1000 person years[23]. Different forms of disease sometimes make the diagnosis difficult and different approaches may be needed. Screening for sleep apnea is not standard practice in the evaluation of syncope[20].

This case report describes a male patient with frequent syncope and seizures with SA related arrhythmia.

An 82-year-old male (BMI: 26 kg/m2) was transferred to our rehabilitation facility after experiencing syncope 3 wk previously. He reported a history of seizures mostly in the morning hours at rest and on the day of the most recent syncope episode he fell down without warning soon after breakfast and was transferred to an emergency unit with a frontal head laceration. The patient also had a history of hypertension, dyslipidaemia, coronary artery disease (CAD) without infarction, bypass surgery (14 years ago) and paroxysmal AF. The patient was taking warfarin, ACE inhibitors, β-blockers, statins and diuretics. In the emergency department, the patient was awake without neurologic impairment. Paroxysmal AF was documented on ECG, without evidence of ischemia or myocardial infarction, and troponin testing was negative. Pulmonary embolism was ruled out. A computed tomographic (CT) scan revealed frontal cerebral haemorrhage, which was treated conservatively and warfarin therapy was stopped. Magnetic resonance (MR) imaging one week later showed that the haemorrhage was resolving.

Some further cardiac evaluation of syncope showed no abnormalities. Twenty four hours blood pressure monitoring was normal. Holter 24-h monitoring revealed sinus rhythm without bradycardia, or tachycardia, or paroxysmal AF. Two-dimensional echocardiography showed normal left ventricular function without valve disease, but no carotid sinus massage, tilting test or electrophysiological studies were performed.

At the rehabilitation facility, the patient was assessed as being well without neurologic disorders. The patient reported snoring and hypersomnia (Epworth Sleepiness Scale score of 9 points, with normal being < 5) and complained of intermediate seizures without falling. Sinus rhythm was present on 12-lead ECG.

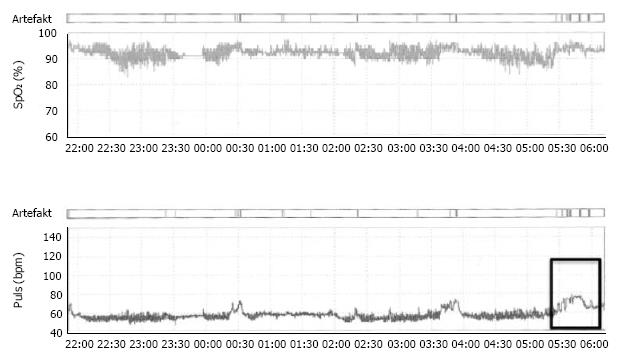

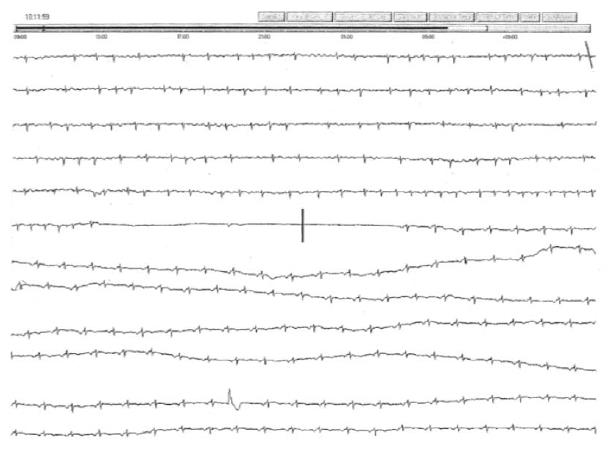

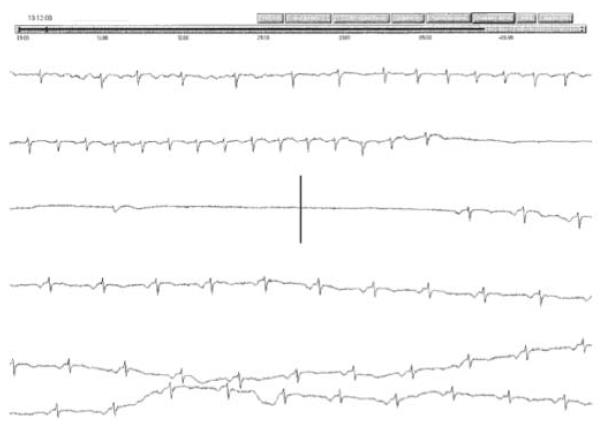

The patient was screened for SA using 2-channel polygraphy (Figure 1), which showed intermittent nocturnal oxygen desaturations and recurrent apneas with an AHI of 35/h. Heart rate data from polygraphy revealed an increase in the morning hours (Figure 1) with arrhythmic pulse curve based on onset of paroxysmal AF during sleep apnea. A second period of 24-h Holter monitoring was performed the following day to evaluate the incidence of paroxysmal AF. Nocturnal paroxysmal AF was seen with onset in the early morning hours, which spontaneously converted to sinus rhythm mid-morning with an arrest of 5 s (sick sinus syndrome) and the patient reported a seizure at the time of the arrest (Figures 2 and 3). The patient was transferred to the cardiac department for pacer implantation (DDD) and then transferred back to the rehabilitation facility for further rehabilitation. Seizures fully resolved after pacemaker implantation and an increase in β-blocker therapy eliminated paroxysmal AF. A further performed polysomnography for SA diagnostics conformed severe OSA (Table 1).

| Polysomnographic parameter | Value |

| AHI (h) | 33 |

| Obstructive apnoea index (h) | 31.4 |

| Central apnoea index (h) | 0 |

| Mixed apnoea index (h) | 0 |

| Hypopnoea index (h) | 1.6 |

| Snoring, min | 9 |

| Mean oxygen saturation (%) | 91 |

| Minimum oxygen saturation (%) | 85 |

| Oxygen desaturation index (h) | 18 |

Treatment of sleep with nasal continuous positive airway pressure (nCPAP) therapy was discussed with the patient but he refused this treatment.

In this case report, sleep apnea screening revealed the nocturnal onset of arrhythmia and facilitated further evaluation of syncope. The temporal relationship between the documented pause in the ECG and seizures in our patient means that this was highly likely to be the underlying cause of the repeated seizures and falls, and ultimately the traumatic injury he sustained. A limitation in this case report is the lack of standard diagnostic for syncope, e.g., carotid sinus massage, tilting test or electrophysiological studies before the rehabilitation setting.

The indication for pacing in our patient was based on syncope with trauma and documentation of sick sinus syndrome in the morning hours after onset of paroxysmal AF. After pacemaker implantation the patient had no further seizures, providing further evidence that sick sinus syndrome was the cause of syncope.

AF and nocturnal bradycardia are often triggered by sleep apnea[24]. This is based on nocturnal hypoxemia and its effects on the cardiac autonomic nerve system[25,26]. Accordingly, our patient was offered, but refused, nCPAP therapy. However, there is evidence to show that CPAP not only effectively treats SA but also reduces nocturnal arrhythmias[27,28]. Although nCPAP therapy can reduce arrhythmia burden and possibly reduce the incidence of paroxysmal AF[24], it is not clear whether nCPAP therapy can prevent all arrhythmias and arrests, justifying the use of a pacemaker in this case. In addition, compliance with nCPAP is necessary for the benefits of therapy to be realised, which is another justification for pacemaker implantation. However, it has been shown that patients with a pacemaker and ongoing syncope have a high incidence of SA[19], indicating that screening for SA in patients with pacemaker implement and syncope would be appropriate.

Sleep disorders are common in TBI and develop in 12%-36 % of patients[16,17,29]. For example, Verma et al[29] found that 50% of patients with TBI reported daytime hypersomnia and 30% were diagnosed with OSA. TBI can result in sleep/wake disturbances, sleep fragmentation, and insomnia or hypersomnia. However, the mechanism of sleep disorders in the setting of TBI is not clear. On one hand the mechanism of injury could trigger sleep disorders such as posttraumatic insomnia or hypersomnia with sleep fragmentation[30,31]. On the other hand, the underlying cause of the accident resulting in TBI may be hypersomnia as a result of nocturnal OSA or, as in this case, nocturnal arrhythmia with syncope and following TBI. Further studies are needed to evaluate the incidence of sleep-related arrhythmias and traumatic injury with the goal of determining whether screening for SA is appropriate in this setting.

Arrhythmias and SA should be considered relevant factors resulting in syncope and trauma. Screening for SA may offer the possibility of additional therapeutic options and diagnostic in trauma and syncope.

An 83-year-old male with traumatic brain injury after syncope of unknown origin in the morning and seizures.

2-channel polygraphy showed intermittent nocturnal oxygen desaturations and recurrent apneas with an apnoea-hypopnoea index (AHI) of 35/h. Heart rate data from polygraphy revealed an increase in the morning hours with arrhythmic pulse curve based on onset of atrial fibrillation (AF) during sleep apnea.

Nocturnal paroxysmal AF was seen with onset in the early morning hours, which spontaneously converted to sinus rhythm mid-morning with an arrest of 5 s (sick sinus syndrome) and the patient reported a seizure at the time of the arrest.

Diagnostic of severe obstructive sleep apnea, AHI 33/h.

Pacer implantation (DDD). Treatment of sleep with nasal continuous positive airway pressure therapy was discussed but refused.

Syncope is the most common cause of traumatic brain injury in the elderly and it often has an underlying cardiovascular aetiology. Arrhythmias and sleep apnea (SA) should be considered relevant factors resulting in syncope and trauma as SA is one trigger of sudden onset of arrhythmia.

Further studies are needed to evaluate the incidence of sleep-related arrhythmias and traumatic injury with the goal of determining whether screening for SA is appropriate in this setting.

This manuscript reports a typical case of sick sinus syndrome in an 83-year-old male, with paroxysmal atrial fibrillation and sinus arrest, presenting clinically with syncope.

P- Reviewer: Gillespie MB, Kolettis TM, Tkacova R S- Editor: Ji FF L- Editor: A E- Editor: Lu YJ

| 1. | Brown DL. Sleep disorders and stroke. Semin Neurol. 2006;26:117-122. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Jean-Louis G, Brown CD, Zizi F, Ogedegbe G, Boutin-Foster C, Gorga J, McFarlane SI. Cardiovascular disease risk reduction with sleep apnea treatment. Expert Rev Cardiovasc Ther. 2010;8:995-1005. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Lanfranchi PA, Braghiroli A, Bosimini E, Mazzuero G, Colombo R, Donner CF, Giannuzzi P. Prognostic value of nocturnal Cheyne-Stokes respiration in chronic heart failure. Circulation. 1999;99:1435-1440. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 489] [Cited by in RCA: 461] [Article Influence: 17.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Bradley TD, Floras JS. Obstructive sleep apnoea and its cardiovascular consequences. Lancet. 2009;373:82-93. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 910] [Cited by in RCA: 932] [Article Influence: 58.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Punjabi NM. The epidemiology of adult obstructive sleep apnea. Proc Am Thorac Soc. 2008;5:136-143. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1329] [Cited by in RCA: 1501] [Article Influence: 88.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 6. | Stradling JR, Davies RJ. Sleep. 1: Obstructive sleep apnoea/hypopnoea syndrome: definitions, epidemiology, and natural history. Thorax. 2004;59:73-78. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 141] [Cited by in RCA: 126] [Article Influence: 6.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Research. TNCoSD. Wake up America: a national sleep alert. Washington DC: US Government Printing Office 2002; . |

| 8. | Durán J, Esnaola S, Rubio R, Iztueta A. Obstructive sleep apnea-hypopnea and related clinical features in a population-based sample of subjects aged 30 to 70 yr. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2001;163:685-689. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 867] [Cited by in RCA: 848] [Article Influence: 35.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Somers VK, White DP, Amin R, Abraham WT, Costa F, Culebras A, Daniels S, Floras JS, Hunt CE, Olson LJ. Sleep apnea and cardiovascular disease: an American Heart Association/american College Of Cardiology Foundation Scientific Statement from the American Heart Association Council for High Blood Pressure Research Professional Education Committee, Council on Clinical Cardiology, Stroke Council, and Council On Cardiovascular Nursing. In collaboration with the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute National Center on Sleep Disorders Research (National Institutes of Health). Circulation. 2008;118:1080-1111. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 898] [Cited by in RCA: 842] [Article Influence: 49.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Parati G, Lombardi C, Hedner J, Bonsignore MR, Grote L, Tkacova R, Levy P, Riha R, Bassetti C, Narkiewicz K. Position paper on the management of patients with obstructive sleep apnea and hypertension: joint recommendations by the European Society of Hypertension, by the European Respiratory Society and by the members of European COST (COoperation in Scientific and Technological research) ACTION B26 on obstructive sleep apnea. J Hypertens. 2012;30:633-646. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 147] [Cited by in RCA: 143] [Article Influence: 11.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Foster GD, Sanders MH, Millman R, Zammit G, Borradaile KE, Newman AB, Wadden TA, Kelley D, Wing RR, Sunyer FX. Obstructive sleep apnea among obese patients with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2009;32:1017-1019. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 377] [Cited by in RCA: 388] [Article Influence: 24.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Tkacova R, McNicholas WT, Javorsky M, Fietze I, Sliwinski P, Parati G, Grote L, Hedner J. Nocturnal intermittent hypoxia predicts prevalent hypertension in the European Sleep Apnoea Database cohort study. Eur Respir J. 2014;44:931-941. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 82] [Cited by in RCA: 112] [Article Influence: 10.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Konecny T, Kuniyoshi FH, Orban M, Pressman GS, Kara T, Gami A, Caples SM, Lopez-Jimenez F, Somers VK. Under-diagnosis of sleep apnea in patients after acute myocardial infarction. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2010;56:742-743. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 85] [Cited by in RCA: 90] [Article Influence: 6.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Bitter T, Westerheide N, Hossain SM, Prinz C, Horstkotte D, Oldenburg O. Symptoms of sleep apnoea in chronic heart failure--results from a prospective cohort study in 1,500 patients. Sleep Breath. 2012;16:781-791. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 47] [Cited by in RCA: 49] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Bazan V, Grau N, Valles E, Felez M, Sanjuas C, Cainzos-Achirica M, Benito B, Jauregui-Abularach M, Gea J, Bruguera-Cortada J. Obstructive sleep apnea in patients with typical atrial flutter: prevalence and impact on arrhythmia control outcome. Chest. 2013;143:1277-1283. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 45] [Cited by in RCA: 48] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Castriotta RJ, Wilde MC, Lai JM, Atanasov S, Masel BE, Kuna ST. Prevalence and consequences of sleep disorders in traumatic brain injury. J Clin Sleep Med. 2007;3:349-356. [PubMed] |

| 17. | Webster JB, Bell KR, Hussey JD, Natale TK, Lakshminarayan S. Sleep apnea in adults with traumatic brain injury: a preliminary investigation. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2001;82:316-321. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 58] [Cited by in RCA: 53] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Mehra R, Redline S. Arrhythmia risk associated with sleep disordered breathing in chronic heart failure. Curr Heart Fail Rep. 2014;11:88-97. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Padeletti M, Vignini S, Ricciardi G, Pieragnoli P, Zacà V, Emdin M, Fumagalli S, Jelic S. Sleep disordered breathing and arrhythmia burden in pacemaker recipients. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol. 2010;33:1462-1466. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Moya A, Sutton R, Ammirati F, Blanc JJ, Brignole M, Dahm JB, Deharo JC, Gajek J, Gjesdal K, Krahn A. Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of syncope (version 2009). Eur Heart J. 2009;30:2631-2671. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1194] [Cited by in RCA: 1226] [Article Influence: 76.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Puel V, Pepin JL, Gosse P. Sleep related breathing disorders and vasovagal syncope, a possible causal link? Int J Cardiol. 2013;168:1666-1667. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Sutton R, Benditt D, Brignole M, Moya A. Syncope: diagnosis and management according to the 2009 guidelines of the European Society of Cardiology. Pol Arch Med Wewn. 2010;120:42-47. [PubMed] |

| 23. | The European Society of Cardiology Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of syncope reviewed by Angel Moya, MD, FESC, Chair of the Guideline Taskforce with J. Taylor, MPhil. Eur Heart J. 2009;30:2539-2540. [PubMed] |

| 24. | Latina JM, Estes NA, Garlitski AC. The Relationship between Obstructive Sleep Apnea and Atrial Fibrillation: A Complex Interplay. Pulm Med. 2013;2013:621736. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 37] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Chaicharn J, Carrington M, Trinder J, Khoo MC. The effects of repetitive arousal from sleep on cardiovascular autonomic control. Conf Proc IEEE Eng Med Biol Soc. 2004;6:3897-3900. [PubMed] |

| 26. | Trinder J, Kleiman J, Carrington M, Smith S, Breen S, Tan N, Kim Y. Autonomic activity during human sleep as a function of time and sleep stage. J Sleep Res. 2001;10:253-264. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 335] [Cited by in RCA: 329] [Article Influence: 13.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Simantirakis EN, Schiza SI, Marketou ME, Chrysostomakis SI, Chlouverakis GI, Klapsinos NC, Siafakas NS, Vardas PE. Severe bradyarrhythmias in patients with sleep apnoea: the effect of continuous positive airway pressure treatment: a long-term evaluation using an insertable loop recorder. Eur Heart J. 2004;25:1070-1076. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 119] [Cited by in RCA: 118] [Article Influence: 5.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Harbison J, O’Reilly P, McNicholas WT. Cardiac rhythm disturbances in the obstructive sleep apnea syndrome: effects of nasal continuous positive airway pressure therapy. Chest. 2000;118:591-595. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 160] [Cited by in RCA: 141] [Article Influence: 5.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Verma A, Anand V, Verma NP. Sleep disorders in chronic traumatic brain injury. J Clin Sleep Med. 2007;3:357-362. [PubMed] |

| 30. | Baumann CR, Werth E, Stocker R, Ludwig S, Bassetti CL. Sleep-wake disturbances 6 months after traumatic brain injury: a prospective study. Brain. 2007;130:1873-1883. [PubMed] |

| 31. | Kempf J, Werth E, Kaiser PR, Bassetti CL, Baumann CR. Sleep-wake disturbances 3 years after traumatic brain injury. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2010;81:1402-1405. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 145] [Cited by in RCA: 143] [Article Influence: 9.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |