Published online Mar 26, 2015. doi: 10.4330/wjc.v7.i3.157

Peer-review started: November 2, 2014

First decision: November 14, 2014

Revised: December 7, 2014

Accepted: January 18, 2015

Article in press: January 20, 2015

Published online: March 26, 2015

Processing time: 131 Days and 15.1 Hours

We are presenting a case of one of the largest un-ruptured abdominal aortic aneurysm ever reported. Presented here is a rare case of a 69-year-old active smoker male with history of hypertension and incidental diagnosis of abdominal aortic aneurysm of 6.2 cm in 2003, who refused surgical intervention at the time of diagnosis with continued smoking habit and was managed medically. Patient was subsequently admitted in 2012 to the hospital due to unresponsiveness secondary to hypoglycemia along with diagnosis of massive symptomatic pulmonary embolism and non-ST elevation myocardial infarction. With the further inpatient workup along with known history of abdominal aortic aneurysm, subsequent computed tomography scan of abdomen pelvis revealed increased in size of infrarenal abdominal aortic aneurysm to 9.1 cm of without any signs of rupture. Patient was unable to undergo any surgical intervention this time because of his medical instability and was eventually passed away under hospice care.

Core tip: Regular screening of patients with abdominal aortic aneurysm with abdominal ultrasound to prevent catastrophic complication of aortic rupture and early aggressive surgical intervention when indicated.

- Citation: Saade C, Pandya B, Raza M, Meghani M, Asti D, Ghavami F. 9.1 cm abdominal aortic aneurysm in a 69-year-old male patient. World J Cardiol 2015; 7(3): 157-160

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1949-8462/full/v7/i3/157.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4330/wjc.v7.i3.157

Abdominal aortic aneurysm is one of the most common conditions seen in elderly hypertensive male with active smoking. Aortic rupture is seen to be the commonest catastrophic complication associated with the condition[1-3]. Purpose of our case report is to illustrate importance of regular screening and timely intervention of abdominal aortic aneurysm along with one of the largest reported image of un-ruptured aortic aneurysm.

A 69-year-old man was brought to the emergency department by emergency medical services (EMS) after being found unresponsive by his partner’s mother. Initially he was detected to be hypoglycemic with blood glucose of less then 30 mg/dL, which was managed by IV dextrose administered by EMS prior to arriving at the hospital.

The patient was diagnosed 6.2 cm infra renal artery aneurysm in 2003. He also had a 3.4 cm saccular aneurysm of the descending thoracic aorta, an aneurysm of 1.9 cm in the common iliac artery, and an aneurysm of the left renal artery. At that time, he decided to receive medical treatment. His past medical history is also significant for systolic congestive heart failure (CHF) mitral regurgitation, myocardial infarction, hypertension, type 2 diabetes mellitus, peripheral vascular disease, smoking (40 packs per year), lower gastrointestinal bleeding and depression. His medications included Aspirin, Carvedilol, Digoxin, Lasix, spironolactone, Lantus insulin, Dexilant, Lorazepam, Gabapentin, and Percocet. Upon arrival to the emergency room in October 2012, the physical exam was characterized by an altered mental status, and he was barely responsive to painful stimuli. He was tachypneic and tachycardic with bilateral rhonchi and rales in respiratory exam, but had stable blood pressure. The rest of his physical exam was unremarkable.

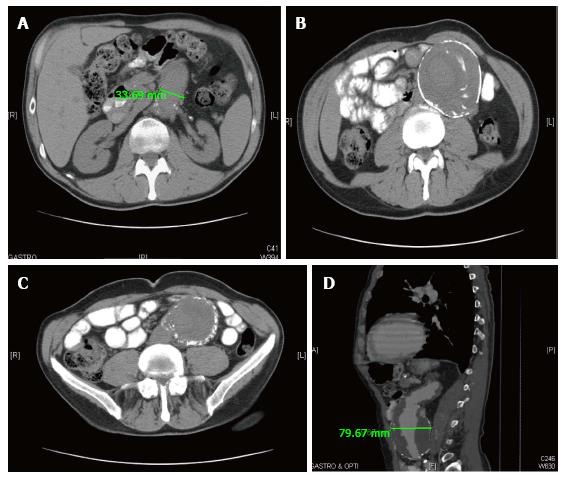

Electrocardiogram showed sinus rhythm with premature ventricular complexes, right bundle branch block, and ST segment depression in inferior leads. Chest X-Ray revealed cardiomegaly and a right lower lobe infiltrate. Computed tomography (CT) scan of the chest with contrast revealed a segmental pulmonary embolism in the right lower lobe consistent with a small infarction, a new 1.0 cm × 0.8 cm × 1 cm marginated left upper lobe pulmonary nodule suspicious for neoplasm, a moderate centrilobular emphysema, small bilateral pleural effusions and a new filling defect within a dilated left ventricle which is suggestive of left ventricular thrombus. CT scan of the abdomen and pelvis with contrast was significant for an increase in size of the descending thoracic aortic aneurysm to 4.2 cm × 3.6 cm, an infrarenal abdominal aorta measuring 9.1 cm × 8.7 cm and right common iliac artery at about 2.4 cm × 2.6 cm. Left renal artery was stable at 3.1 cm × 2.7 cm. There was no evidence of rupture in the abdominal aortic aneurysm.

The patient had elevated troponins level possibly due to a NSTEMI. He received IV heparin to manage pulmonary embolism and possible NSTEMI. Considering his extensive medical history, poor medical management outcome and deteriorating mental condition, his family decided to place the patient in hospice care on 10/10/12. The patient died on 10/12/12.

Aortic aneurismal disease is defined as a focal dilation of the aorta with a diameter greater than 3.5 cm. Thoracic aneurysms are located above the diaphragm. The abdominal aneurysm is more common and is located below the diaphragm with a prevalence of 1.4% in the United States population age 50 to 84[2]. Aortic rupture is the most common complication of these aneurysms with a mortality rate as high as 75% for the abdominal aneurysm[3]. The profile of a patient that might have an aneurysm and eventually may benefit from a screening test would be a man between 65 and 75 with a history of smoking or a younger patient with a family history of a genetic disease associated with aneurysms[1,4]. The 2005 United States Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) report recommended ultrasonography as the screening test for the abdominal aneurysm with a sensitivity rate as high as 100%. Multiple risk predictors for the growth and rupture of an AAA were determined and included: continuous smoking which is the major risk factor, female gender, diastolic hypertension, maximum transverse diameter > 5.5 cm, and dyslipidemia[1,4-9]. On the other hand, other factors were found to decrease the growth rate and subsequently the risk of rupture of abdominal aortic aneurysm (AAA). The use of statins in a recent metanalysis[10] has been shown to reduce by 0.63 mm/year the growth rate of the AAA. Both macrolides and tetracyclines[11-13] were associated with a lower expansion rate of the AAA. However, propanolol use hasn’t been beneficial in preventing the growth rate of AAA in a double-blind randomized study[14]. When it comes to surgical management, the threshold recognized currently is 5.5 cm or above. This was demonstrated in two trials conducted in the United Kingdom and United States[6,7]. A CT scan is warranted as part of the preoperative planning because it can help characterizing the AAA for a better surgical approach.

Our patient had both thoracic and abdominal aneurysms with the latter measuring 9.1 cm as a maximum diameter at the time of his death. To our knowledge, this is the largest unruptured AAA to be diagnosed. The patient was incidentally diagnosed to have an AAA of 6.6 cm on CT scan (Figure 1). The incidental finding of an AAA is as high as 0.5% on CT scan as reported in Al-Tahani study[15]. Even though the patient was eligible for surgical reparation of the AAA, he refused the operation knowing the risks of his decision. Between 2003 and 2012, the patient continued to smoke and was taking medications for his hypertension and CHF. He had thus 2 major risk factors for the growth of his AAA considering that his hypertension was medically controlled. In 2012, the size of his AAA increased to 9.1 cm thus at a rate of 0.32 cm/year. At this point, the patient was inoperable because of his worsening CHF and his massive pulmonary embolism. The CT scan also showed the continuous growth of the thoracic aneurysm and the right common iliac artery aneurysm. As per Brown et al study[9], this male patient with an AAA greater than 6 cm had a 14.1% risk per year of having a ruptured AAA. The Helsinki study[16] showed that in 154 cases excluded from the surgical repair of AAA due to severe co morbidities in the patients, 43% eventually died because of a ruptured AAA. Therefore, it can be postulated that the patient had an imminent risk for AAA rupture. No autopsy was done as per the request of the family but it might be speculated that the patient’s death was due to ruptured AAA especially that he had to be started on therapeutic heparin for his massive symptomatic PE.

A 69-year-old male presented with hypoglycemia found to have 9.1 cm × 8.7 cm unruptured AAA.

Patient was found to have subsequent pulmonary embolism and Non ST elevation Myocardial infarction.

CT scan of the abdomen and pelvis with contrast was significant for an increase in size of the descending thoracic aortic aneurysm to 4.2 cm × 3.6 cm, an infrarenal abdominal aorta measuring 9.1 cm × 8.7 cm and right common iliac artery at about 2.4 cm × 2.6 cm.

Due to patient’s medical instability, he was not a surgical candidate.

So far reported cases in literatures are either ruptured abdominal aortic aneurysm or not significantly enlarged. Reported here is case of unruptured largest abdominal aortic aneurysm, which can be managed successfully with timely intervention.

Regular screening of patients with abdominal aortic aneurysm with abdominal ultrasound helps prevent catastrophic complication of aortic rupture and early aggressive surgical intervention when indicated.

This is a well-written clinical case report regarding to the large un-ruptured abdominal aortic aneurysm. The case is interesting and illustrates importance of regular screening and timely intervention of abdominal aortic aneurysm, which will gather the great interests from the readers.

P- Reviewer: Bonanno C, Dizon JM, O-Uchi J S- Editor: Song XX L- Editor: A E- Editor: Lu YJ

| 1. | Cury M, Zeidan F, Lobato AC. Aortic disease in the young: genetic aneurysm syndromes, connective tissue disorders, and familial aortic aneurysms and dissections. Int J Vasc Med. 2013;2013:267215. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | LaBoon A, Mastracci TM. A 67-year old man with an abdominal aortic aneurysm. Cleve Clin J Med. 2013;80:161-167. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Hans SS, Jareunpoon O, Balasubramaniam M, Zelenock GB. Size and location of thrombus in intact and ruptured abdominal aortic aneurysms. J Vasc Surg. 2005;41:584-588. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 153] [Cited by in RCA: 139] [Article Influence: 7.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Fleming C, Whitlock EP, Beil TL, Lederle FA. Screening for abdominal aortic aneurysm: a best-evidence systematic review for the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Ann Intern Med. 2005;142:203-211. [PubMed] |

| 5. | Mofidi R, Goldie VJ, Kelman J, Dawson AR, Murie JA, Chalmers RT. Influence of sex on expansion rate of abdominal aortic aneurysms. Br J Surg. 2007;94:310-314. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 99] [Cited by in RCA: 109] [Article Influence: 6.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Mortality results for randomised controlled trial of early elective surgery or ultrasonographic surveillance for small abdominal aortic aneurysms. The UK Small Aneurysm Trial Participants. Lancet. 1998;352:1649-1655. [PubMed] |

| 7. | Lederle FA, Wilson SE, Johnson GR, Reinke DB, Littooy FN, Acher CW, Ballard DJ, Messina LM, Gordon IL, Chute EP. Immediate repair compared with surveillance of small abdominal aortic aneurysms. N Engl J Med. 2002;346:1437-1444. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 838] [Cited by in RCA: 748] [Article Influence: 32.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Larsson E, Labruto F, Gasser TC, Swedenborg J, Hultgren R. Analysis of aortic wall stress and rupture risk in patients with abdominal aortic aneurysm with a gender perspective. J Vasc Surg. 2011;54:295-299. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 44] [Cited by in RCA: 43] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Brown PM, Zelt DT, Sobolev B. The risk of rupture in untreated aneurysms: the impact of size, gender, and expansion rate. J Vasc Surg. 2003;37:280-284. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 233] [Cited by in RCA: 232] [Article Influence: 10.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Takagi H, Mizuno Y, Yamamoto H, Goto SN, Umemoto T. Alice in Wonderland of statin therapy for small abdominal aortic aneurysm. Int J Cardiol. 2013;166:252-255. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Vammen S, Lindholt JS, Ostergaard L, Fasting H, Henneberg EW. Randomized double-blind controlled trial of roxithromycin for prevention of abdominal aortic aneurysm expansion. Br J Surg. 2001;88:1066-1072. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 120] [Cited by in RCA: 111] [Article Influence: 4.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Baxter BT, Pearce WH, Waltke EA, Littooy FN, Hallett JW, Kent KC, Upchurch GR, Chaikof EL, Mills JL, Fleckten B. Prolonged administration of doxycycline in patients with small asymptomatic abdominal aortic aneurysms: report of a prospective (Phase II) multicenter study. J Vasc Surg. 2002;36:1-12. [PubMed] |

| 13. | Mosorin M, Juvonen J, Biancari F, Satta J, Surcel HM, Leinonen M, Saikku P, Juvonen T. Use of doxycycline to decrease the growth rate of abdominal aortic aneurysms: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled pilot study. J Vasc Surg. 2001;34:606-610. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 239] [Cited by in RCA: 214] [Article Influence: 8.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Propanolol Aneurysm Trial Investigators. Propranolol for small abdominal aortic aneurysms: results of a randomized trial. J Vasc Surg. 2002;35:72-79. [PubMed] |

| 15. | Al-Thani H, El-Menyar A, Shabana A, Tabeb A, Al-Sulaiti M, Almalki A. Incidental abdominal aneurysms: a retrospective study of 13,115 patients who underwent a computed tomography scan. Angiology. 2014;65:388-395. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Noronen K, Laukontaus S, Kantonen I, Lepäntalo M, Venermo M. The natural course of abdominal aortic aneurysms that meet the treatment criteria but not the operative requirements. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2013;45:326-331. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |