Published online Sep 26, 2014. doi: 10.4330/wjc.v6.i9.924

Revised: July 11, 2014

Accepted: July 17, 2014

Published online: September 26, 2014

Processing time: 282 Days and 3.2 Hours

Reperfusion of myocardial tissue is the main goal of primary percutaneous coronary intervention (PPCI) with stent implantation in the treatment of acute ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI). Although PPCI has contributed to a dramatic reduction in cardiovascular mortality over three decades, normal myocardial perfusion is not restored in approximately one-third of these patients. Several mechanisms may contribute to myocardial reperfusion failure, in particular distal embolization of the thrombus and plaque fragments. In fact, this is a possible complication during PPCI, resulting in microvascular obstruction and no-reflow phenomenon. The presence of a visible thrombus at the time of PPCI in patients with STEMI is associated with poor procedural and clinical outcomes. Aspiration thrombectomy during PPCI has been proposed to prevent embolization in order to improve these outcomes. In fact, the most recent guidelines suggest the routine use of manual aspiration thrombectomy during PPCI (class IIa) to reduce the risk of distal embolization. Even though numerous international studies have been reported, there are conflicting results on the clinical impact of aspiration thrombectomy during PPCI. In particular, data on long-term clinical outcomes are still inconsistent. In this review, we have carefully analyzed literature data on thrombectomy during PPCI, taking into account the most recent studies and meta-analyses.

Core tip: Distal coronary embolization occurs predominantly at the time of the initial balloon or stent inflation, so thrombus burden reduction by thrombectomy devices before percutaneous coronary intervention may decrease the dangerous phenomenon of no-reflow. Manual aspiration catheters are the most commonly used devices. Several randomized trials have demonstrated the efficacy and safety of pretreatment with manual thrombectomy during primary percutaneous coronary intervention. There are some unanswered questions about thrombus aspiration, including whether there is truly a mortality benefit, which subgroups may or may not benefit from aspiration, and whether patients with a large thrombus burden are better treated with mechanical thrombectomy.

- Citation: Sardella G, Stio RE. Thrombus aspiration in acute myocardial infarction: Rationale and indication. World J Cardiol 2014; 6(9): 924-928

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1949-8462/full/v6/i9/924.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4330/wjc.v6.i9.924

The final objective of primary percutaneous coronary intervention (PPCI) is successful myocardial reperfusion[1]. Apart from restoration of flow in the epicardial coronary artery, the importance of cardiac muscle microcirculation has been emphasized[2,3]. Myocardial reperfusion failure has been associated with larger infarct size, increased predisposition to ventricular arrhythmias, heart failure, cardiogenic shock, recurrent myocardial infarction, and cardiac death[4,5].

Different mechanisms are responsible for microvascular injury after PPCI, such as local formation of a thrombus, generation of oxygen-free radicals, myocyte calcium overload, cellular and interstitial edema, endothelial dysfunction, vasoconstriction, and inflammation. However, distal embolization seems to play a pivotal role, and thrombus burden is a predictor of the no-reflow phenomenon and an independent predictor of adverse outcomes[6-10].

Distal coronary embolization occurs predominantly at the time of initial balloon or stent inflation, so thrombus burden reduction by thrombectomy devices before balloon/stent inflation may decrease the dangerous phenomenon of no-reflow[11]. Manual aspiration catheters are the most commonly used devices because they are easy and safe to use, even in the elderly[12], and are relatively inexpensive compared with rheolytic thrombectomy[13]. Moreover, myocardial salvage is measured and studied in trials through different parameters: angiographic [thrombolysis in myocardial infarction (TIMI) and myocardial blush grade (MBG)], electrocardiographic [ST-segment resolution (STR)], functional (reduction of infarct size) and clinical (enhanced survival free from heart failure events)[14,15]. Several randomized trials have demonstrated the efficacy and safety of pretreatment with manual thrombectomy during PPCI. Most of the studies in the literature, including meta-analyses, randomized trials or registries, conclude that thrombectomy improves the parameters of myocardial reperfusion, with a rapid and effective STR[16]. The Thrombus Aspiration during Percutaneous coronary intervention in Acute myocardial infarction (TAPAS) Trial, the impact of thrombectomy with EXPort catheter in Infarct-Related Artery during Primary Percutaneous Coronary Intervention (EXPIRA) Trial and some meta-analyses found that aspiration thrombectomy during ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) improves myocardial reperfusion and procedural outcomes, reducing no-reflow, mortality and distal embolization[17-19]. There are some unanswered questions about thrombus aspiration including whether there is truly a mortality benefit[20], which subgroups may and may not benefit from aspiration, and whether patients with large thrombus burden are better treated with mechanical thrombectomy.

There are many ways to treat the coronary thrombus burden at the time of PPCI: pharmacologic strategies (typically glycoprotein IIb/IIIa platelet inhibitors), embolic protection devices (filters and distal balloon occlusion with aspiration), mechanical thrombectomy, and manual or aspiration thrombectomy devices. This paper reviews the role of manual thrombectomy in patients with STEMI. The evidence supporting the benefit of aspiration thrombectomy on surrogate outcomes (TIMI flow, MBG and STR) and angiographic outcomes (distal embolization and no-reflow) is strong and convincing, while the benefit in reduction of mortality is not strong and has limitations[19-24].

All randomized trials of aspiration thrombectomy have been performed in “all comers” with STEMI, and it is not clear which subgroups may benefit more and which subgroups may not benefit at all. In the EXPIRA Trial, 175 patients with STEMI were randomized to PPCI alone vs PPCI with manual thrombectomy and a significant improvement was shown in the primary endpoints of MBG 3 and complete STR. This study was the first to evaluate infarct size by magnetic resonance imaging, and it found that the extent of microvascular obstruction was less in the acute phase with aspiration (1.7 g vs 3.7 g, P = 0.0003), and an improvement in infarct size at 3 mo was seen with aspiration (17% to 11%, P = 0.004) but not in the control group (14% to 13%, P = NS)[18]. These data are confirmed by the results of the INFUSE-AMI Trial (Intracoronary Abciximab Infusion and Aspiration Thrombectomy in Patients Undergoing Percutaneous Coronary Intervention for Anterior ST-Segment Elevation Myocardial Infarction) in which the group with thrombectomy plus intracoronary abciximab had a better prognosis[25].

Based on the TAPAS Trial and the above meta-analyses, the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Guidelines and the European Society of Cardiology Guidelines have given aspiration thrombectomy a Class IIa (Level of Evidence B) indication in PPCI for STEMI. The committee did not consider the evidence for benefit on clinical outcomes strong enough to warrant a Class I indication[22].

The literature and clinical practice clearly show that the impact of thrombectomy on all outcomes is linked to multiple factors during STEMI, in particular time from symptom onset to PCI, and infarct-related coronary artery and intracoronary thrombus burden.

Sianos et al[26] have shown that both angiographic and clinical outcomes are poorer in patients with a large thrombus burden (≥ 2 vessel diameters) in a new thrombus classification. A large thrombus burden is associated with a greater frequency of major adverse cardiac events, and is a strong independent predictor of late mortality. Moreover, Napodano et al[27] found that patients with right coronary artery infarcts, long lesions and a high thrombus score had the highest frequency of distal embolization. We might expect these subgroups to benefit most from thrombectomy, but data from the TAPAS trial do not support this. Improvement in MBG with aspiration was no better in patients with right coronary artery (RCA) infarcts vs non-RCA infarcts, and was no better in patients with a visible thrombus compared with patients without a visible thrombus. There was a trend for greater benefit in patients with a reperfusion time of less than 3 h, but there were no differential benefits in patients stratified by pre-PCI TIMI flow[17]. Overall, there are few current studies to support selective use of aspiration thrombectomy in any subgroup of STEMI patients treated with PPCI[28-30].

Recently, the TASTE Trial (Thrombus Aspiration in ST-Elevation myocardial infarction in Scandinavia), a randomized study using a platform of a clinical registry, enrolled 7244 STEMI patients who were treated with standard PPCI or manual thrombectomy before PCI. This trial had an ambitious primary endpoint, that is, to reduce 30-d all-cause mortality, and it concluded that routine thrombectomy in PPCI does not reduce this event[31]. In our opinion, in this study, it was excessive to expect a mortality reduction at 30 d, and would have been more logical to have a primary end-point with a mean follow-up of at least 1 year, as in TAPAS. The TASTE trial design was based on national heart registries and on a secondary randomization that could introduce an initial bias; moreover, there were no reported procedural data such as TIMI flow post-aspiration, MBG or STR. Finally, the frequency of thrombus score greater than 3 was very low (32%) in the total population (54% of patients in the TASTE trial). Instead in the EXPIRA trial, an important inclusion criteria was a higher visible thrombus burden (score ≥ 3) identifying patients at highest risk of coronary distal embolization. Data reported in the literature and guidelines indicate that manual thrombus aspiration should always be considered during PPCI to reduce the risk of distal embolization, in particular in cases of intraluminal thrombosis with a score ≥ 3.

Aspiration thrombectomy has limited ability to remove a large thrombus and may sometimes be associated with incomplete thrombus removal, no-reflow, and/or distal emboli. There is previous and very recent evidence that mechanical thrombectomy may effectively improve outcomes in patients with a large thrombus burden. Whether mechanical thrombectomy is preferable to aspiration thrombectomy in patients with a large thrombus burden remains an unanswered question[32].

In our opinion, based on the literature and clinical practice, manual thrombectomy can be used as first approach during PPCI to prevent distal embolization in the case of a visible thrombus burden. As demonstrated in the RETAMI trial, the new generation manual thrombectomy devices are superior to the first generation tools to remove a greater thrombotic burden, providing higher post-thrombectomy epicardial flow and better post-stenting microvascular reperfusion[33].

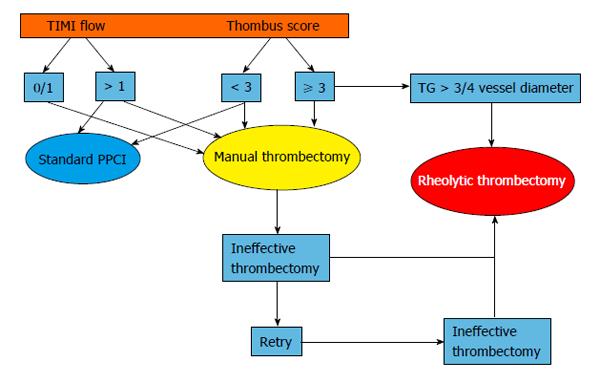

From a “real world point of view”, to perform a good manual thrombectomy, the culprit vessel diameter could be > 2.5 mm with a TIMI flow 0-1 and a visible thrombus (score > 3). The device, however, has to advance delicately over the thrombotic occlusion to perform continuous intracoronary blood suction. In the case of a large thrombus burden, it is now possible to use a 7 Fr intracoronary manual thrombectomy device or rheolytic tools with greater suction force (Figure 1). In conclusion, in the treatment of acute myocardial infarction, thrombectomy should be considered as one of the most important therapeutic tools, with the purpose of cardioprotection and myocardial salvage.

P- Reviewer: Akdemir R, Lazzeri C S- Editor: Wen LL L- Editor: Cant MR E- Editor: Liu SQ

| 1. | Grines CL, Cox DA, Stone GW, Garcia E, Mattos LA, Giambartolomei A, Brodie BR, Madonna O, Eijgelshoven M, Lansky AJ. Coronary angioplasty with or without stent implantation for acute myocardial infarction. Stent Primary Angioplasty in Myocardial Infarction Study Group. N Engl J Med. 1999;341:1949-1956. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 670] [Cited by in RCA: 623] [Article Influence: 24.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Gibson CM, Cannon CP, Murphy SA, Ryan KA, Mesley R, Marble SJ, McCabe CH, Van De Werf F, Braunwald E. Relationship of TIMI myocardial perfusion grade to mortality after administration of thrombolytic drugs. Circulation. 2000;101:125-130. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 599] [Cited by in RCA: 590] [Article Influence: 23.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Hoffmann R, Haager P, Lepper W, Franke A, Hanrath P. Relation of coronary flow pattern to myocardial blush grade in patients with first acute myocardial infarction. Heart. 2003;89:1147-1151. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Braunwald E. The treatment of acute myocardial infarction: the Past, the Present, and the Future. Eur Heart J Acute Cardiovasc Care. 2012;1:9-12. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 46] [Cited by in RCA: 54] [Article Influence: 4.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Montalescot G, Barragan P, Wittenberg O, Ecollan P, Elhadad S, Villain P, Boulenc JM, Morice MC, Maillard L, Pansiéri M. Platelet glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibition with coronary stenting for acute myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med. 2001;344:1895-1903. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 831] [Cited by in RCA: 766] [Article Influence: 31.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Turer AT, Hill JA. Pathogenesis of myocardial ischemia-reperfusion injury and rationale for therapy. Am J Cardiol. 2010;106:360-368. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 496] [Cited by in RCA: 483] [Article Influence: 32.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Stone GW, Grines CL, Cox DA, Garcia E, Tcheng JE, Griffin JJ, Guagliumi G, Stuckey T, Turco M, Carroll JD. Comparison of angioplasty with stenting, with or without abciximab, in acute myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med. 2002;346:957-966. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 934] [Cited by in RCA: 854] [Article Influence: 37.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | van ‘t Hof AW, Liem A, de Boer MJ, Zijlstra F. Clinical value of 12-lead electrocardiogram after successful reperfusion therapy for acute myocardial infarction. Zwolle Myocardial infarction Study Group. Lancet. 1997;350:615-619. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 415] [Cited by in RCA: 418] [Article Influence: 14.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | White CJ, Ramee SR, Collins TJ, Escobar AE, Karsan A, Shaw D, Jain SP, Bass TA, Heuser RR, Teirstein PS. Coronary thrombi increase PTCA risk. Angioscopy as a clinical tool. Circulation. 1996;93:253-258. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 139] [Cited by in RCA: 128] [Article Influence: 4.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Kotani J, Nanto S, Mintz GS, Kitakaze M, Ohara T, Morozumi T, Nagata S, Hori M. Plaque gruel of atheromatous coronary lesion may contribute to the no-reflow phenomenon in patients with acute coronary syndrome. Circulation. 2002;106:1672-1677. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 198] [Cited by in RCA: 190] [Article Influence: 8.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Henriques JP, Zijlstra F, Ottervanger JP, de Boer MJ, van ‘t Hof AW, Hoorntje JC, Suryapranata H. Incidence and clinical significance of distal embolization during primary angioplasty for acute myocardial infarction. Eur Heart J. 2002;23:1112-1117. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 458] [Cited by in RCA: 461] [Article Influence: 20.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Valente S, Lazzeri C, Mattesini A, Chiostri M, Giglioli C, Meucci F, Baldereschi G, Gensini GF. Thrombus aspiration in elderly STEMI patients: a single center experience. Int J Cardiol. 2013;168:3097-3099. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Rochon B, Chami Y, Sachdeva R, Bissett JK, Willis N, Uretsky BF. Manual aspiration thrombectomy in acute ST elevation myocardial infarction: New gold standard. World J Cardiol. 2011;3:43-47. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Desch S, Eitel I, de Waha S, Fuernau G, Lurz P, Gutberlet M, Schuler G, Thiele H. Cardiac magnetic resonance imaging parameters as surrogate endpoints in clinical trials of acute myocardial infarction. Trials. 2011;12:204. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 40] [Cited by in RCA: 45] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | De Luca L, Sardella G, Davidson CJ, De Persio G, Beraldi M, Tommasone T, Mancone M, Nguyen BL, Agati L, Gheorghiade M. Impact of intracoronary aspiration thrombectomy during primary angioplasty on left ventricular remodelling in patients with anterior ST elevation myocardial infarction. Heart. 2006;92:951-957. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 112] [Cited by in RCA: 114] [Article Influence: 5.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | De Vita M, Burzotta F, Biondi-Zoccai GG, Lefevre T, Dudek D, Antoniucci D, Orrego PS, De Luca L, Kaltoft A, Sardella G. Individual patient-data meta-analysis comparing clinical outcome in patients with ST-elevation myocardial infarction treated with percutaneous coronary intervention with or without prior thrombectomy. ATTEMPT study: a pooled Analysis of Trials on ThrombEctomy in acute Myocardial infarction based on individual PatienT data. Vasc Health Risk Manag. 2009;5:243-247. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Vlaar PJ, Svilaas T, van der Horst IC, Diercks GF, Fokkema ML, de Smet BJ, van den Heuvel AF, Anthonio RL, Jessurun GA, Tan ES. Cardiac death and reinfarction after 1 year in the Thrombus Aspiration during Percutaneous coronary intervention in Acute myocardial infarction Study (TAPAS): a 1-year follow-up study. Lancet. 2008;371:1915-1920. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 630] [Cited by in RCA: 595] [Article Influence: 35.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Sardella G, Mancone M, Bucciarelli-Ducci C, Agati L, Scardala R, Carbone I, Francone M, Di Roma A, Benedetti G, Conti G. Thrombus aspiration during primary percutaneous coronary intervention improves myocardial reperfusion and reduces infarct size: the EXPIRA (thrombectomy with export catheter in infarct-related artery during primary percutaneous coronary intervention) prospective, randomized trial. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009;53:309-315. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 273] [Cited by in RCA: 269] [Article Influence: 16.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Sardella G, Mancone M, Canali E, Di Roma A, Benedetti G, Stio R, Badagliacca R, Lucisano L, Agati L, Fedele F. Impact of thrombectomy with EXPort Catheter in Infarct-Related Artery during Primary Percutaneous Coronary Intervention (EXPIRA Trial) on cardiac death. Am J Cardiol. 2010;106:624-629. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 38] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Kilic S, Ottervanger JP, Dambrink JH, Hoorntje JC, Koopmans PC, Gosselink AT, Suryapranata H, van ‘t Hof AW. The effect of thrombus aspiration during primary percutaneous coronary intervention on clinical outcome in daily clinical practice. Thromb Haemost. 2014;111:165-171. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | O’Gara PT, Kushner FG, Ascheim DD, Casey DE, Chung MK, de Lemos JA, Ettinger SM, Fang JC, Fesmire FM, Franklin BA. 2013 ACCF/AHA guideline for the management of ST-elevation myocardial infarction: executive summary: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines: developed in collaboration with the American College of Emergency Physicians and Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2013;82:E1-27. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1728] [Cited by in RCA: 1901] [Article Influence: 146.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Task Force on the management of ST-segment elevation acute myocardial infarction of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC), Steg PG, James SK, Atar D, Badano LP, Blömstrom-Lundqvist C, Borger MA, Di Mario C, Dickstein K, Ducrocq G, Fernandez-Aviles F, Gershlick AH, Giannuzzi P, Halvorsen S, Huber K, Juni P, Kastrati A, Knuuti J, Lenzen MJ, Mahaffey KW, Valgimigli M, van ‘t Hof A, Widimsky P, Zahger D. ESC Guidelines for the management of acute myocardial infarction in patients presenting with ST-segment elevation. Eur Heart J. 2012;33:2569-2619. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3540] [Cited by in RCA: 3702] [Article Influence: 284.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Brodie BR. Aspiration thrombectomy with primary PCI for STEMI: review of the data and current guidelines. J Invasive Cardiol. 2010;22:2B-5B. [PubMed] |

| 24. | Ali A, Cox D, Dib N, Brodie B, Berman D, Gupta N, Browne K, Iwaoka R, Azrin M, Stapleton D. Rheolytic thrombectomy with percutaneous coronary intervention for infarct size reduction in acute myocardial infarction: 30-day results from a multicenter randomized study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2006;48:244-252. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 216] [Cited by in RCA: 186] [Article Influence: 9.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Stone GW, Maehara A, Witzenbichler B, Godlewski J, Parise H, Dambrink JH, Ochala A, Carlton TW, Cristea E, Wolff SD. Intracoronary abciximab and aspiration thrombectomy in patients with large anterior myocardial infarction: the INFUSE-AMI randomized trial. JAMA. 2012;307:1817-1826. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 390] [Cited by in RCA: 402] [Article Influence: 30.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Sianos G, Papafaklis MI, Serruys PW. Angiographic thrombus burden classification in patients with ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction treated with percutaneous coronary intervention. J Invasive Cardiol. 2010;22:6B-14B. [PubMed] |

| 27. | Napodano M, Ramondo A, Tarantini G, Peluso D, Compagno S, Fraccaro C, Frigo AC, Razzolini R, Iliceto S. Predictors and time-related impact of distal embolization during primary angioplasty. Eur Heart J. 2009;30:305-313. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 68] [Cited by in RCA: 77] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Fröbert O, Lagerqvist B, Olivecrona GK, Omerovic E, Gudnason T, Maeng M, Aasa M, Angerås O, Calais F, Danielewicz M. Thrombus aspiration during ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med. 2013;369:1587-1597. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 778] [Cited by in RCA: 827] [Article Influence: 68.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Burzotta F, De Vita M, Gu YL, Isshiki T, Lefèvre T, Kaltoft A, Dudek D, Sardella G, Orrego PS, Antoniucci D. Clinical impact of thrombectomy in acute ST-elevation myocardial infarction: an individual patient-data pooled analysis of 11 trials. Eur Heart J. 2009;30:2193-2203. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 191] [Cited by in RCA: 181] [Article Influence: 11.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Kumbhani DJ, Bavry AA, Desai MY, Bangalore S, Bhatt DL. Role of aspiration and mechanical thrombectomy in patients with acute myocardial infarction undergoing primary angioplasty: an updated meta-analysis of randomized trials. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013;62:1409-1418. [PubMed] |

| 31. | Ole Fröbert, Bo Lagerqvist, Göran K. Olivecrona, Omerovic E, Gudnason T, Maeng M, Aasa M, Angerås O, Calais F, Danielewicz M, Erlinge D, Hellsten L, Jensen U, Johansson AC, Kåregren A, Nilsson J, Robertson L, Sandhall L, Sjögren I, Ostlund O, Harnek J, James SK; TASTE Trial. Thrombus Aspiration during ST-Segment Elevation Myocardial Infarction. N Engl J Med. 2013;369:1587-1597. |

| 32. | Migliorini A, Stabile A, Rodriguez AE, Gandolfo C, Rodriguez Granillo AM, Valenti R, Parodi G, Neumann FJ, Colombo A, Antoniucci D. Comparison of AngioJet rheolytic thrombectomy before direct infarct artery stenting with direct stenting alone in patients with acute myocardial infarction. The JETSTENT trial. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2010;56:1298-1306. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 127] [Cited by in RCA: 117] [Article Influence: 7.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Sardella G, Mancone M, Nguyen BL, De Luca L, Di Roma A, Colantonio R, Petrolini A, Conti G, Fedele F. The effect of thrombectomy on myocardial blush in primary angioplasty: the Randomized Evaluation of Thrombus Aspiration by two thrombectomy devices in acute Myocardial Infarction (RETAMI) trial. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2008;71:84-91. [PubMed] |