Published online Sep 26, 2014. doi: 10.4330/wjc.v6.i9.1041

Revised: June 27, 2014

Accepted: July 15, 2014

Published online: September 26, 2014

Processing time: 261 Days and 12.7 Hours

We present the case of a young woman corrected with a Mustard procedure undergoing successful transvenous double chamber pacemaker implantation with the atrial lead placed in the systemic venous channel. The case presented demonstrates that, when the systemic venous atrium is separate from the left atrial appendage, the lead can be easily and safely placed in the systemic venous left atrium gaining satisfactory sensing and pacing thresholds despite consisting partially of pericardial tissue.

Core tip: Disturbances of rhythm in patients undergoing Mustard Procedure are common and they often require implantation of a permanent pacemaker with the atrial lead usually screwed into the left atrial appendage. The case presented demonstrates that, when the systemic venous atrium is separate from the left atrial appendage, the lead can be easily and safely placed in the systemic venous left atrium gaining satisfactory sensing and pacing thresholds despite consisting partially of pericardial tissue.

- Citation: Puntrello C, Lucà F, Rubino G, Rao CM, Gelsomino S. Systemic venous atrium stimulation in transvenous pacing after mustard procedure. World J Cardiol 2014; 6(9): 1041-1044

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1949-8462/full/v6/i9/1041.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4330/wjc.v6.i9.1041

The mustard operation (MO)[1] was a well-established method to correct the transposition of the great arteries before being superseded, in the recent years, by anatomic repair, the so called arterial switch operation[2,3]. The procedure employs a pericardial baffle to change the direction of the blood flow from the systemic venous return to the left ventricle and pulmonary venous return to the right ventricle[1].

Disturbances of rhythm and conduction in patients undergoing MO-have been the focus of many studies[4-6]. Occasionally a permanent pacemaker is needed especially for patients with symptomatic sick sinus syndrome.

Usually one electrode is put in the apex of the anatomic left (subpulmonary) ventricle and the atrial lead is fixed into the left atrial appendage[4].

Nonetheless, if the the systemic venous atrium does not include the left atrial appendage it is impossible to screw the atrial lead into the left atrial appendage. In addition, it is questionable whether, positioning the electrode in the systemic venous atrium, sensing capabilities are inadequate as the neo-atrium consists partially of pericardial tissue and whether the electrode remains in the correct position.

We present the case of a young woman corrected with a Mustard procedure undergoing successful transvenous double chamber pacemaker implantation with the atrial lead placed in the systemic venous channel.

A 32-year-old female was born with a transposition of the great arteries (TGA), a large defect of the ventricular septum and a persistent ductus. At six months old she had a MO which involved closure of the defect of the ventricular septum and ductus arteriosus.

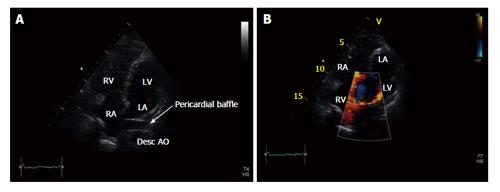

After the operation, she showed no symptoms at regular outpatient clinics. Nonetheless, 31 years after the MO she experienced dizziness, progressive tiredness, and shortness of breath. Echocardiography revealed a good left and right ventricular function (Figure 1).

With Holter monitoring we observed periods of atrioventricular junctional escape rhythm, high degree of atrioventricular block and pauses of up to 5.4 s. Indication was given for a pacemaker implantation. Due to the dizzy spells caused by sinus node dysfunction in addition to atrioventricular conduction disturbances, the patient was subjected to a transvenous double chamber pacemaker implantation. Through the left cephalic vein an active-fixation electrode was introduced and placed in the apex of the anatomic left (subpulmonary) ventricle. Satisfactory values of sensing (8 mV) and pacing thresholds (0.5 mV) were gained without diaphragmatic stimulation.

In this patient the left atrial appendage was kept outside of venous tissue and therefore the passive-fixation atrial lead was inserted into the systemic venous channel and a loop was created.

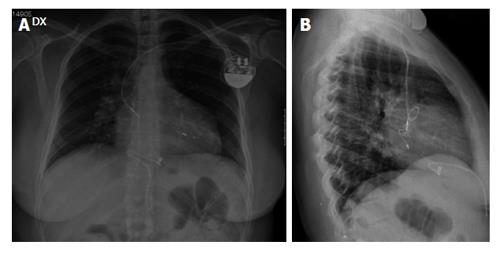

Sensing and pacing thresholds were 1 mV and 2 V per 0.5 ms respectively. Post-procedural X-ray confirmed adequate positioning of the leads (Figure 2). The patient was discharged after an uneventful postoperative course.

At the 5-year follow up the leads were still in the correct position and sensing and pacing values were not subject to change. The woman was asymptomatic in sinus rhythm with a regular ventricular activation driven from the atrium.

TGA accounts for 5% to 7% of all congenital heart anomalies[7]. The surgical repairs for TGA were first introduced by Senning in 1959; Mustard modified this technique in 1964[1].

At the moment an anatomical correction is the most extensively used procedure; and the arterial switch has largely taken the place of the atrial switch procedure. Nonetheless late development of both atrial arrhythmias are well recognized late complications of atrial baffle surgery[4-11] (Table 1).

| Complications |

| Lead dislodgement |

| Lead positioning |

| Abnormal anatomy post surgery |

| Spontaneous systemic venous baffle and venous obstruction |

| Systemic venous baffle and venous obstruction after lead insertion |

| Ventricular rhythm disturbances |

| Pacing thresholds, pacing impedance and sensing inadequate measurments or variations |

| System erosion/infection |

| Endocarditis risk |

| Paradoxical thromboembolic events |

Intra-atrial re-entrant tachycardia is the most common arrhythmia found among these patients, which has been associated with development of heart failure and death[5,9].

In particular, causes of arrhythmias after the Mustard repair include[4,12,13]: (1) damage during surgery to the sinus node or sinus node artery; (2) break of intra-atrial conduction by interruption of internodal pathways; and (3) intraoperative damage to atrioventricular (AV) node conduction tissue.

Pacemaker implantation is indicated for patients after MO who have a HR < 30 beats/min, Stokes-Adams episodes, patients requiring pharmacological therapy for tachyarrhythmias, or those with a poor systemic ventricular function and bradycardia[14,15]. In addition, some MO patients require pacemaker implantation for sinus node dysfunction, AV block, in order to permit medical therapy of tachyarrhythmias or as an anti-tachycardia therapy[16].

Pacemaker implantation in this setting can be technically challenging because of the complex anatomy[17] and the possibility of complications such as systemic venous baffle obstruction or left innominate vein, right/left subclavian vein obstruction[18]. Therefore, the determination of the exact vascular anatomy is mandatory to decide the most suitable position for placing the leads.

In this regard echocardiography, venography or intravenous digital subtraction angiography before implantation may be of great help in studying the anatomy structural variations before pacemaker implantation.

However, usually one electrode is placed in the apex of the anatomic left (subpulmonary) ventricle-and the atrial lead is fixed to the left atrial appendage[7]. Berul et al[19] suggests, in the postoperative Mustard procedure, that the superior aspect of the systemic venous-left atrium is the most optimal location.

Nonetheless, when left atrial appendage is not in place or it is not included into the systemic venous atrium, it is impossible to screw the atrial lead into the left atrial appendage. The electrode may be positioned in the systemic venous atrium but, as it consists partially of pericardial tissue, there are concerns associated with obtaining suboptimal sensing and pacing thresholds and, despite this, there are no studies addressing the feasibility and efficacy of transvenous leads implanted into the pericardial baffle.

We present the case of a 32-year-old female undergoing a Mustard operation at six months of age who had transvenous double chamber pacemaker implantation because of high-degree atrioventricular block.

The ventricular electrode was placed in its usual position in the apex of the anatomic left (subpulmonary) ventricle avoiding creating a loop in this location which can be a substrate for ventricular ectopic beats[4]. In contrast, since the left atrial appendage was outside the systemic venous atrium, it was impossible to place the lead into the left auricular appendix. Therefore, the atrial lead was positioned in the systemic venous channel and a passive fixation pacing was chosen to avoid pericardial baffle damage. Nonetheless, the use of passive-fixation pacing may lead to electrode dislodgement and this risk is raised by the absence of trabecular structures in the systemic venous channel differently from the left atrial appendage. Therefore, to prevent lead dislodgement, we created an electrode loop in the tube-like systemic venous channel.

At the end of the procedure sensing and pacing thresholds were adequate and, after 5 years, leads were still in the correct position with unchanged sensing and pacing thresholds.

In conclusion, the case of our patient demonstrates that in patients after Mustard repair, when the left atrial appendage in not reachable for surgical or anatomical reasons, the lead can be easily and safely placed in the systemic venous left atrium gaining satisfactory sensing and pacing thresholds and with no risk of lead dislodgement.

We gratefully acknowledge Professor James Douglas for the English revision of the paper.

A 32-year-old female born with a transposition of the great arteries (TGA), a large ventricular septal defect and a patent ductus arteriosus who underwent a mustard operation (MO) at six months of age.

Progressive fatigue and dizziness and shortness of breath 31 years after her operation.

Mobitz I second-degree atrioventricular (AV) block from Mobitz II second-degree AV block, as well as Mobitz II second-degree AV block from third-degree AV block.

Echocardiography, venography or intravenous digital subtraction angiography prior to implantation may be of great help in studying the anatomy structural variations before pacemaker implantation.

Holter monitoring showed episodes of atrioventricular junctional escape rhythm and high degree atrioventricular block.

Indication was given for a pacemaker implantation.

Some MO patients require pacemaker implantation for sinus node dysfunction, AV block, to permit medical therapy of tachyarrhythmias or as anti tachycardia therapy.

Mustard Operation is surgical treatment of TGA nowadays an anatomical correction is more preferred and this arterial switch procedure has largely replaced MO.

The case presented demonstrates that, when the left atrial appendage is not included into the systemic venous atrium, the lead can be easily and safely placed in the systemic venous left atrium gaining satisfactory sensing and pacing thresholds despite it consists partially of pericardial tissue.

A well-written case report merits consideration for publication as it describes a novel idea for permanent pacing in a patient with Mustard procedure.

P- Reviewer: Letsas K, Petix NR, Raja SG S- Editor: Wen LL L- Editor: A E- Editor: Liu SQ

| 1. | Mustard WT. Successful two-stage correction of transposition of the great vessels. Surgery. 1964;55:469-472. [PubMed] |

| 2. | Junge C, Westhoff-Bleck M, Schoof S, Danne F, Buchhorn R, Seabrook JA, Geyer S, Ziemer G, Wessel A, Norozi K. Comparison of late results of arterial switch versus atrial switch (mustard procedure) operation for transposition of the great arteries. Am J Cardiol. 2013;111:1505-1509. [PubMed] |

| 3. | Oechslin E, Jenni R. 40 years after the first atrial switch procedure in patients with transposition of the great arteries: long-term results in Toronto and Zurich. Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2000;48:233-237. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 74] [Cited by in RCA: 63] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Hayes CJ, Gersony WM. Arrhythmias after the Mustard operation for transposition of the great arteries: a long-term study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1986;7:133-137. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 113] [Cited by in RCA: 96] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Frankel DS, Shah MJ, Aziz PF, Hutchinson MD. Catheter ablation of atrial fibrillation in transposition of the great arteries treated with mustard atrial baffle. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol. 2012;5:e41-e43. [PubMed] |

| 6. | Gelatt M, Hamilton RM, McCrindle BW, Connelly M, Davis A, Harris L, Gow RM, Williams WG, Trusler GA, Freedom RM. Arrhythmia and mortality after the Mustard procedure: a 30-year single-center experience. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1997;29:194-201. [PubMed] |

| 7. | Konings TC, Dekkers LR, Groenink M, Bouma BJ, Mulder BJ. Transvenous pacing after the Mustard procedure: considering the complications. Neth Heart J. 2007;15:387-389. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Gatzoulis MA, Walters J, McLaughlin PR, Merchant N, Webb GD, Liu P. Late arrhythmia in adults with the mustard procedure for transposition of great arteries: a surrogate marker for right ventricular dysfunction? Heart. 2000;84:409-415. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 104] [Cited by in RCA: 88] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Kammeraad JA, van Deurzen CH, Sreeram N, Bink-Boelkens MT, Ottenkamp J, Helbing WA, Lam J, Sobotka-Plojhar MA, Daniels O, Balaji S. Predictors of sudden cardiac death after Mustard or Senning repair for transposition of the great arteries. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2004;44:1095-1102. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 223] [Cited by in RCA: 195] [Article Influence: 9.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Tobler D, Williams WG, Jegatheeswaran A, Van Arsdell GS, McCrindle BW, Greutmann M, Oechslin EN, Silversides CK. Cardiac outcomes in young adult survivors of the arterial switch operation for transposition of the great arteries. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2010;56:58-64. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 126] [Cited by in RCA: 124] [Article Influence: 8.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Duster MC, Bink-Boelkens MT, Wampler D, Gillette PC, McNamara DG, Cooley DA. Long-term follow-up of dysrhythmias following the Mustard procedure. Am Heart J. 1985;109:1323-1326. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 55] [Cited by in RCA: 51] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Gillette PC, el-Said GM, Sivarajan N, Mullins CE, Williams RL, McNamara DG. Electrophysiological abnormalities after Mustard’s operation for transposition of the great arteries. Br Heart J. 1974;36:186-191. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 80] [Cited by in RCA: 75] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Isaacson R, Titus JL, Merideth J, Feldt RH, McGoon DC. Apparent interruption of atrial conduction pathways after surgical repair of transposition of great arteries. Am J Cardiol. 1972;30:533-535. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 74] [Cited by in RCA: 77] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Hornung TS, Derrick GP, Deanfield JE, Redington AN. Transposition complexes in the adult: a changing perspective. Cardiol Clin. 2002;20:405-420. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Amikam S, Lemer J, Kishon Y, Riss E, Neufeld HN. Complete heart block in an adult with corrected transposition of the great arteries treated with permanent pacemaker. Thorax. 1979;34:547-549. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Gewillig M, Cullen S, Mertens B, Lesaffre E, Deanfield J. Risk factors for arrhythmia and death after Mustard operation for simple transposition of the great arteries. Circulation. 1991;84:III187-III192. [PubMed] |

| 17. | el-Said G, Rosenberg HS, Mullins CE, Hallman GL, Cooley DA, McNamara DG. Dysrhythmias after Mustard’s operation for transposition of the treat arteries. Am J Cardiol. 1972;30:526-532. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 156] [Cited by in RCA: 135] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Patel S, Shah D, Chintala K, Karpawich PP. Atrial baffle problems following the Mustard operation in children and young adults with dextro-transposition of the great arteries: the need for improved clinical detection in the current era. Congenit Heart Dis. 2011;6:466-474. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Berul CI, Cecchin F. Indications and techniques of pediatric cardiac pacing. Expert Rev Cardiovasc Ther. 2003;1:165-176. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |