INTRODUCTION

Hypertension is a major cause of premature death and disability in the world mainly as a result of cardiovascular disease including coronary heart disease and stroke, and other vascular diseases[1,2]. This burden of ill-health represents an economic burden, which is attributable not only to antihypertensive medication but also to very expensive procedures such as percutaneous coronary intervention, coronary artery bypass grafts, neurosurgical treatment, or hemodialysis that are required in cases of serious vascular diseases that occur more frequently in hypertensive than normotensive individuals. Therefore, only prospective cohort studies can measure medical expenditure attributable solely to hypertension in the general population. This fundamental information is required when considering the cost-effectiveness of treating and preventing hypertension.

Japan provides an ideal situation to measure medical expenditure attributable to hypertension, as it is possible to use epidemiological methods to analyse data on health checkups and medical expenditure. Health checkups are commonly conducted in communities and worksites in Japan, whereas data on medical expenditure are available from the medical insurance system that controls medical cost nationwide and is compulsory for all Japanese residents (see ACKNOWLEDGMENTS)[3-5]. Several epidemiological studies have used these merits to examine the relationship between hypertension status and medical expenditure after a follow-up period in Japanese populations. The objective of this article is to review articles published on these epidemiological studies in Japan.

SEARCH STRATEGY AND SELECTION

We performed a systematic search on Medline for relevant articles published between January 1966 and January 2014. We searched using medical subject headings (MeSH) terms and text words: {(hypertension [MeSH term], including MeSH terms found below this term in the MeSH tree) or (hypertension [text word]) or (high blood pressure [text word])} and {(costs and cost analysis [MeSH term], including MeSH terms found below this term in the MeSH tree) or (cost [text word]) or (expenditure [text word]) or (expense [text word])} and {(Japan [text word])}. We restricted the search to English language articles so that everyone could read the full texts if necessary. Using this search strategy we identified a total of 163 articles. We set the following inclusion criteria that suited the objectives of our study: (1) prospective cohort, but not cross-sectional studies, that examined the relationship between hypertension status and subsequent medical expenditure; (2) studies conducted in a general Japanese population, but not a population that consisted solely of individuals with a particular high-risk condition or hospital patients; (3) hypertension status assessed by blood pressure measurement and/or medical history of taking antihypertensive medication, with medical expenditure being measured using insurance claim history files of the Japanese medical insurance system; and (4) studies that provided evidence about how much medical expenditure is incurred by hypertension and/or evidence on any relevant topics. We read the titles and abstracts of all the articles identified in the Medline search to exclude any articles that seemed irrelevant. The full texts of the remaining articles were read to determine if they met our inclusion criteria. Of the 163 articles identified, only six articles were considered as relevant and met our inclusion criteria. Although we manually searched for extra relevant articles in the reference lists of the identified articles and other publications, no additional relevant article was identified from these sources. Of the six relevant articles, three articles were from the same cohort study, but each dealt with different topics without duplicate publication[6-8]. The remaining three articles were all different[9-11].

HYPERTENSION AND MEDICAL EXPENDITURE

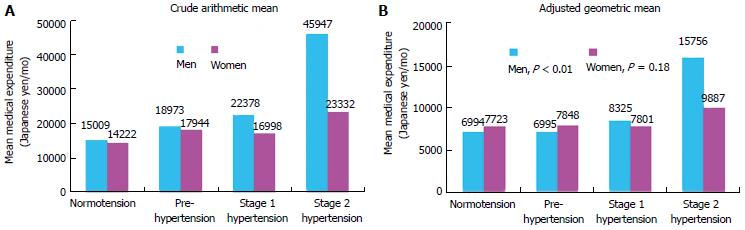

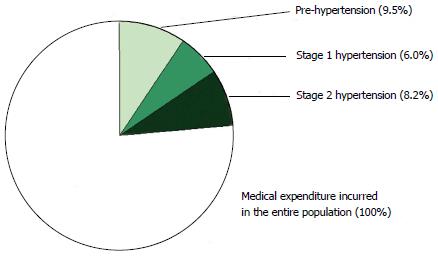

The first study to report on the relationship between hypertension status and subsequent medical expenditure was the Shiga National Health Insurance (NHI) cohort study[6]. This study was conducted in seven towns and one village in Shiga prefecture in the central part of Japan, and included 4191 community-dwelling beneficiaries of NHI, an insurance group for self-employed individuals (e.g., farmers and fishermen) and retirees and their dependants. The study participants were aged between 40-69 years and were not taking antihypertensive medication and did not have a history of cardiovascular disease. They were classified into four sex-specific categories according to their blood pressure measured at a baseline survey in 1989-1991. The four blood pressure categories were defined as follows according to the 7th report of the Joint National Committee in the United States[12]: “normotension” (systolic blood pressure (SBP) < 120 mmHg and diastolic blood pressure (DBP) < 80 mmHg); “pre-hypertension” (SBP 120-139 mmHg and/or DBP 80−89 mmHg); “stage 1 hypertension” (SBP 140-159 mmHg and/or DBP 90-99 mmHg); and “stage 2 hypertension” (SBP ≥ 160 mmHg and/or DBP ≥ 100 mmHg). The participants were followed up for 10 years from 1990 to calculate the mean medical expenditure per month during the follow-up period. The cumulative hospitalization rate and all-cause mortality for each blood pressure category were also recorded. If a participant withdrew or died, the follow-up period was terminated at that point. The medical expenditure recorded in this study was confined to the fee schedule range used in the medical insurance system in Japan, and was calculated as the sum of expenditure from the insurance organization and the beneficiary. The crude arithmetic mean of medical expenditure increased with worsening severity of hypertension, especially in men (Figure 1A). The adjusted geometric mean of medical expenditure, calculated using analysis of covariance that incorporated logarithmically-transformed values of medical expenditure as the dependent variable and major cardiovascular risk factors as covariates, also correlated positively with blood pressure levels (Figure 1B). The odds ratio for cumulative hospitalization (1.96, 95%CI: 1.29-2.98) and hazard ratio for all-cause mortality (3.19, 95%CI: 1.67-6.08) in stage 2 hypertensive men were also higher than those in normotensive men after adjustment for potential confounding factors. This study estimated medical expenditure attributable to the three grades of hypertension (i.e., “pre-hypertension”, “stage 1 hypertension”, and “stage 2 hypertension”) from a population perspective. The medical expenditure attributable to these three hypertension grades accounted for 23.7% of the medical expenditure incurred in the combined male and female study participants (Figure 2). The percentage for each-hypertension-related medical expenditure was 9.5% for “pre-hypertension”, 6.0% for “stage 1 hypertension”, and 8.2% for “stage 2 hypertension”.

Figure 1 Crude arithmetic mean (A) and adjusted geometric mean (B) of medical expenditure per month over 10 years of follow-up in male and female Japanese medical insurance beneficiaries aged 40-69 years, grouped according to sex and hypertension status.

Analysis of covariance was used to compare log-transformed monthly medical expenditure in each blood pressure category, after adjustment for age, body mass index, smoking habit, drinking habit, serum total cholesterol, and a history of diabetes. From Nakamura et al[6].

Figure 2 Percentage of medical expenditure attributable to pre-, stage 1, and stage 2 hypertension relative to medical expenditure incurred by the entire population of Japanese medical insurance beneficiaries aged 40-69 years (100%).

From Nakamura et al[6].

The Ohsaki NHI cohort study[9] was conducted subsequently in Ohsaki city, Miyagi prefecture in the northeast part of Japan using a similar method. This study included 12340 community-dwelling NHI beneficiaries aged 40-79 years without a history of cardiovascular disease or cancer. The study participants were classified into the following two categories according to their blood pressure and antihypertensive medication status assessed in 1994-1995: “normotension” (SBP < 140 mmHg, DBP < 90 mmHg, and not taking antihypertensive medication); and “hypertension” (SBP ≥ 140 mmHg, DBP ≥ 90 mmHg and/or taking antihypertensive medication). The arithmetic mean of medical expenditure per month during the 6-year follow-up period from 1996 was higher in hypertensive participants than in normotensive participants even after adjustment for age, sex, smoking and alcohol drinking habits, and obesity, hyperglycaemia, and dyslipidemia status: 275.9 United States dollars/mo vs 203.5 United States dollars/mo, respectively (1 United States dollar = 115 Japanese yen at the foreign exchange rate given in the article). When the hypertensive participants were divided further into untreated and treated hypertensive subjects, the mean medical expenditure was increased further in the treated hypertensive group than in the untreated hypertensive and normotensive groups: 317.7 United States dollars/mo vs 223.0 United States dollars/mo vs 202.9 United States dollars/mo, respectively.

The Ibaraki NHI cohort study[10], which was conducted over a wide area in Ibaraki prefecture in the eastern part of Japan, used a similar, but partially different method. This study included 42426 community-dwelling NHI beneficiaries aged 40-69 years without a history of cardiovascular disease. The study measured medical expenditure for just one year (2006), four years after the baseline survey in 2002 that assessed hypertension status. Monthly medical expenditure was compared for the same four blood pressure categories as those used in the Shiga NHI cohort study, although stage 2 hypertension included both participants who had a SBP ≥ 160 mmHg and/or DBP ≥ 100 mmHg free from antihypertensive medication and those on antihypertensive medication. The median medical expenditure increased with more severe hypertension in every stratum of age (i.e., 40-54 years and 55-69 years) and sex.

HYPERTENSION COMBINED WITH ANOTHER RISK FACTOR AND MEDICAL EXPENDITURE

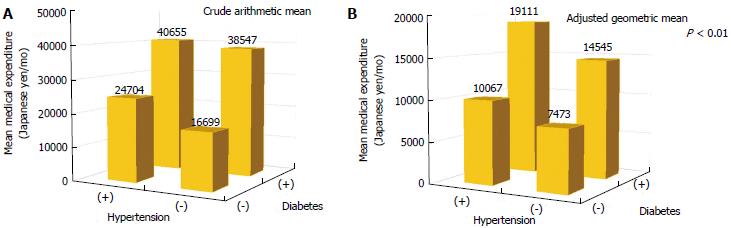

The Shiga NHI cohort study[7] examined the relationship between the combination of hypertension status and diabetes status and subsequent medical expenditure in 4535 participants. This patient group was selected as the coexistence of hypertension and diabetes is often due mainly to insulin resistance accompanied by compensatory hyperinsulinemia[13,14], which occurs more frequently in obese than in non-obese individuals[15,16]. The mean of medical expenditure per month over a 10-year follow-up period was compared in the following four categories: “neither hypertension nor diabetes”; “hypertension alone”; “diabetes alone”; and “both hypertension and diabetes”. Hypertension was defined as a SBP ≥ 140 mmHg, a DBP ≥ 90 mmHg, and/or taking antihypertensive medication, while diabetes was defined as having a history of diabetes assessed by a self-reported questionnaire. The participants with both hypertension and diabetes, who accounted for 1.3% of the study population, incurred on average, higher medical expenditure compared with those without hypertension, diabetes, or their combination, even after adjustment for confounding factors (Figure 3). Similarly, the “both hypertension and diabetes” group had the highest risk of all-cause mortality among the four categories, with an adjusted hazard ratio of 2.21 (95%CI: 1.11-4.42), relative to the “neither hypertension nor diabetes” group.

Figure 3 Crude arithmetic mean (A) and adjusted geometric mean (B) of medical expenditure per month over 10 years of follow-up in Japanese medical insurance beneficiaries aged 40-69 years, grouped according to hypertension and diabetes status.

Analysis of covariance was used to compare log-transformed monthly medical expenditure in each blood pressure category, after adjustment for age, sex, body mass index, smoking habit, drinking habit, and serum total cholesterol. From Nakamura et al[7].

The Ohsaki NHI cohort study[9] compared mean medical expenditure per month over a 6-year follow-up period in four similar categories in participants stratified according to the presence or absence of obesity defined as a body mass index ≥ 25.0 kg/m2. Hypertension was defined as described earlier, whereas hyperglycemia was defined as a plasma glucose ≥ 150 mg/dL and/or having a self-reported history of diabetes. The results of this study showed a pattern similar to those of the Shiga NHI cohort study for both obese and non-obese participants, although obesity resulted in additional medical expenditure in each of the four blood pressure and plasma glucose categories. In short, non-obese participants with both hypertension and hyperglycemia, with hypertension alone and with hyperglycemia alone had increased medical expenditure of 85.2%, 33.0% and 48.3%, respectively, compared with non-obese participants with neither hypertension nor hyperglycemia. In contrast, obese participants with both hypertension and hyperglycemia had a 91.0% increase in expenditure compared with the same reference group. The medical expenditure attributable to both hypertension and hyperglycemia with and without obesity accounted for 1.4% and 1.8% of the medical expenditure incurred in the entire population, respectively.

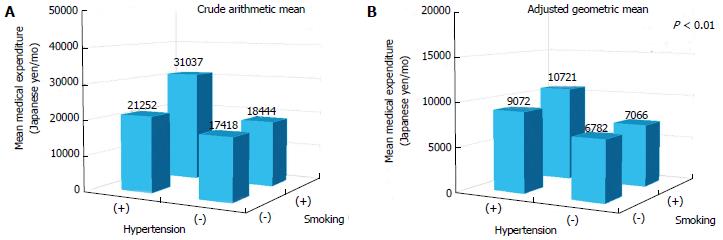

The Shiga NHI cohort study[8] examined the relationship between the combination of hypertension status and smoking status and subsequent medical expenditure in 1708 male participants after excluding male ex-smokers and all females, as smoking is more prevalent in Japanese men than in Japanese women[17]. Mean medical expenditure per month over a 10-year follow-up period was compared in the following four categories: “neither hypertension nor smoking”; “hypertension alone”; “smoking alone”; and “both hypertension and smoking”. Hypertension was defined as described earlier, while smoking was defined as currently smoking. Participants with both hypertension and smoking, who accounted for 24.9% of the study population, incurred on average, higher medical expenditure compared with those without hypertension, smoking, or their combination, even after adjustment for confounding factors (Figure 4).

Figure 4 Crude arithmetic mean (A) and adjusted geometric mean (B) of medical expenditure per month over 10 years of follow-up in male Japanese medical insurance beneficiaries aged 40-69 years, grouped according to hypertension and smoking status.

Analysis of covariance was used to compare log-transformed monthly medical expenditure in each blood pressure category, after adjustment for age, body mass index, drinking habit, serum total cholesterol, and a history of diabetes. From Nakamura et al[8].

OTHER RELEVANT TOPICS

The latest cohort study collected similar data throughout Japan, and reported interesting results which revealed how hospitalization influenced the causality between hypertension and increased medical expenditure[11]. Unlike the three previous cohort studies, this study included both NHI beneficiaries (12 local organizations) and beneficiaries in the Employee’s Health Insurance scheme (nine local organizations), which is available for employees and their dependants. Currently, all Japanese people younger than 75 years should be enrolled in either NHI or Employee’s Health Insurance schemes (enrolment ratio, 1:2)[3]. A total of 314622 participants aged 40-69 years without a history of cardiovascular disease or end-stage renal disease were included in the final analyses. The study participants were age and sex-specifically classified into seven categories according to their blood pressure and antihypertensive medication status assessed at the baseline survey in 2008. The seven blood pressure categories were defined according to the 2007 criteria of the European Society of Hypertension and the European Society of Cardiology[18]. Participants who were not taking antihypertensive medication were classified into one of the following five categories: “optimal blood pressure” (SBP < 120 mmHg and DBP < 80 mmHg); “normal-to-high normal blood pressure” (SBP 120–139 mmHg and/or DBP 80-89 mmHg); “grade 1 hypertension” (SBP 140-159 mmHg and/or DBP 90-99 mmHg); “grade 2 hypertension” (SBP 160-179 mmHg and/or DBP 100-109 mmHg); and “grade 3 hypertension” (SBP ≥ 180 mmHg and/or DBP ≥ 110 mmHg). The remaining participants, who were taking antihypertensive medication, were classified into one of the following two categories: “well controlled hypertension on treatment” (SBP < 140 mmHg and DBP < 90 mmHg on medication); and “poorly controlled hypertension on treatment” (SBP ≥ 140 mmHg and/or DBP ≥ 90 mmHg on medication). This study first compared the risk of undergoing hospitalization one year (2009) after the baseline survey in each blood pressure category. In men aged 40-54 or 55-69 years, the risk of undergoing hospitalization in 2009, especially long-term hospitalization, increased with worsening severity of untreated hypertension (bars in Figure 5, results presented only for men and women aged 40-54 years). The “grade 2-to-3 untreated hypertension” group appeared to have a further increased risk of being hospitalized for at least 14 cumulative days than the “well controlled hypertension on treatment” group. The results derived from the female cohorts need to be interpreted with caution because of the lower prevalence of hypertension and the small number of hospitalizations in females compared with males. However, in women aged 40-54 years, the “grade 3 untreated hypertension” group appeared to have a further increase in hospitalization risk compared with the “well controlled hypertension on treatment” group. Participants who were hospitalized, especially long-term, incurred considerably higher medical expenditure compared with non-hospitalized participants, regardless of their hypertension status, age, or sex. Hypertensive participants on medication appeared to incur less than half of the medical expenditure of hospitalized participants, as long as they remained out of hospital for treatment of hypertension alone. However, this study did not clarify whether the use of antihypertensive medication could offset long-term medical expenditure.

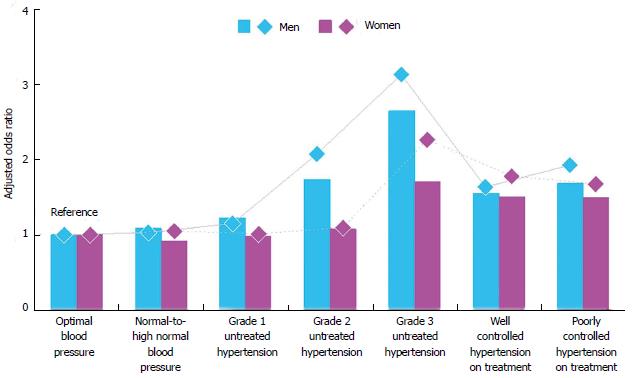

Figure 5 Adjusted odds ratios for two kinds of events over one year of follow-up in male and female Japanese medical insurance beneficiaries aged 40-54 years, grouped according to hypertension status.

The bars represent the risk of undergoing hospitalization for ≥ 14 cumulative days, while the diamonds represent the risk of falling into the top 1% group of medical expenditure. A logistic regression model was used to calculate odds ratios after adjustment for age, body mass index, smoking habit, serum low-density lipoprotein cholesterol, log-transformed fasting plasma glucose, and medications for hypercholesterolemia and diabetes, with the “optimal blood pressure” group acting as the reference. Male and female participants who fell into the sex-specific top 1% medical expenditure group each incurred ≥ 1571 euros/mo and ≥ 1249 euros/mo, respectively (1 euro = 95.91 Japanese yen). From Nakamura et al[11].

The study also compared the risk of incurring extremely high medical expenditure, defined as at least 99th percentile values of the sex-specific distribution of medical expenditure in the year after the baseline survey in each of the blood pressure categories. This comparison was made because of the fact that a very small percentage of patients accounts for a substantial percentage of the medical expenditure in the entire population[19]. Male and female participants who fell into the top 1% group of medical expenditure incurred at least 1571 euros/mo and 1249 euros/mo, respectively (1 euro = 95.91 Japanese yen at the foreign exchange rate given in the article), with the corresponding median cumulative hospitalization periods being 38 and 32 d. The sum of medical expenditure in these top 1% male and female groups accounted for 25.6% and 21.2% of medical expenditure in the entire population, respectively. The risk of incurring such extremely high medical expenditure increased with more severe untreated hypertension in men aged 40-54 or 55-69 years and in women aged 40-54 years (diamonds in Figure 5, results presented only for men and women aged 40-54 years). In men and women aged 40-54 years, the “grade 2-to-3 untreated hypertension” group had a further increased risk of incurring greater medical expenditure compared with the “well controlled hypertension on treatment” group. These results were consistent with the results regarding the risk of being hospitalized for at least 14 cumulative days.

CONCLUSION

Epidemiological studies demonstrated that hypertension caused increased medical expenditure in community-dwelling populations in Japan. Medical expenditure was increased further in hypertensive subjects who had another concomitant cardiovascular risk factor. These studies therefore show that the treatment of hypertension itself is costly. However, attention should be paid to evidence that hypertension, especially moderate-to-severe untreated hypertension, increased the risk of long-term hospitalization, which resulted in considerably higher medical expenditure compared with non-hospitalized cases. Furthermore, hypertension, especially moderate-to-severe untreated hypertension, increased the risk of surges in medical expenditure, due mainly to long-term hospitalization. Therefore, based on the assumption that use of antihypertensive medication is essential for hypertensive subjects to prevent serious vascular diseases[20,21], a cost-effective high-risk strategy needs to be considered in order to reduce both ill-health and the economic burden due to hypertension. It should also be noted that from a population perspective, medical expenditure attributable to hypertension appears to results largely from pre-to-mild hypertension, although personal hypertension-related medical expenditure is higher with more severe hypertension. This is in accordance with Rose”s theory that “a large number of people exposed to a small risk may generate many more cases than a small number exposed to high risk”[22]. Too much focus on hypertensive subjects, especially those with moderate-to-severe hypertension may result in failure to comprehensively reduce the burden of interest. Therefore, there is also a need to consider a population strategy, which aims to shift the entire population to lower levels of blood pressure.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The medical insurance system in Japan

This system requires the enrolment of all Japanese residents (i.e., “health-insurance-for-all”). Every Japanese resident is able to receive medical services at all clinics and hospitals given approval to provide outpatient medical services and hospitalization. This system consists of three insurance groups (previously two insurance groups) with eligibility for each group depending on the individual’s age and occupation. The fee schedule set by the National Government is uniform across the insurance groups and applies to all the approved clinics and hospitals. Prices are controlled strictly by a fee schedule and are determined on a “fee-for-service” basis. However, recently approximately 20% of acute care hospitals have changed to a flat-fee per day payment system for hospitalized patients according to the diagnosis and procedures undertaken (Diagnosis Procedure Combination/Per-Diem Payment System). The clinic or hospital requests medical expenditure from the insurance organization in which the beneficiary is enrolled and also the beneficiary himself/herself, with the insurance organization paying 70%-90% and the beneficiary paying the balance. However, the medical insurance system does not cover some medical services including health checkups for asymptomatic individuals or inoculations, with annual health checkups available free or at fairly low charges in communities and worksites.

P- Reviewer: Bahlmann F, Efstathiou S S- Editor: Wen LL L- Editor: A E- Editor: Wu HL