Published online May 26, 2014. doi: 10.4330/wjc.v6.i5.349

Revised: March 11, 2014

Accepted: March 17, 2014

Published online: May 26, 2014

Processing time: 171 Days and 14.7 Hours

Aortic size index (ASI) has been proposed as a reliable criterion to predict risk for aortic dissection in Turner syndrome with significant thresholds of 20-25 mm/m2. We report a case of aortic arch dissection in a patient with Turner syndrome who, from the ASI thresholds proposed, was deemed to be at low risk of aortic dissection or rupture and was not eligible for prophylactic surgery. This case report strongly supports careful monitoring and surgical evaluation even when the ASI is < 20 mm/m2 if other significant risk factors are present.

Core tip: Aortic size index (ASI) has been proposed as a reliable criterion to predict risk of aortic dissection in Turner syndrome. This case report emphasizes the need for careful monitoring and surgical evaluation of the patients even when the ASI is < 20 mm/m2 if other significant risk factors are present.

- Citation: Nijs J, Gelsomino S, Lucà F, Parise O, Maessen JG, Meir ML. Unreliability of aortic size index to predict risk of aortic dissection in a patient with Turner syndrome. World J Cardiol 2014; 6(5): 349-352

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1949-8462/full/v6/i5/349.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4330/wjc.v6.i5.349

Turner syndrome (TS) is a relatively common chromosomal disorder, caused by complete or partial X monosomy in some or all cells[1]. This abnormality is denoted medically as the 45,X karyotype as opposed to the usual 46,XX female karyotype. Many TS patients are actually mosaic, meaning that they have cells with more than one karyotype and occasionally there is mosaicism for cells containing Y chromosome material (Table 1)[2-4]. Short stature and gonadal dysgenesis are two of the characteristic clinical features of the syndrome, although many organ systems and tissues may also be affected to a lesser or greater extent. However, approximately 50% of karyotypically-proven, asymptomatic women with TS have evidence of abnormal cardiovascular development and most patients die from cardiovascular defects mainly involving the left ventricular outflow tract, left heart and/or aortic hypoplasia. Common congenital defects in surviving girls and adults with TS include bicuspid aortic valve (30%), aortic coarctation (12%) and partial anomalous pulmonary connection (18%)[5,6]. Nonetheless, the occurrence of aortic dilatation, dissection or rupture is one of major concerns in TS[7]. The annual incidence of aortic dissection or rupture is 15 cases/100000 for individuals < 20 years of age, 73-78 cases/100000 for women 20-40 years old and 50/100000 for older women with TS[5].

| Karyotype | Description | El-Mansoury et al[2] 2007(n = 126) | Gravolt et al[3] 1996(n = 304) | Hook et al[4] 1983(n = 1043) |

| 45,X | Monosomy X | 48% | 56% | 58% |

| 45,X/46,XX | Monosomy X mosaic with normal female sex chromosome complement | 23% | 17% | 15% |

| 46,X,i(Xq) | isochromosome X | 13% | 11% | 15% |

| 46,X,del(X) | deletion chromosome X | - | 8% | 6% |

| 46,X,r(X) | ring chromosome X | 3% | 5% | 2% |

| 45,X/47, XXX | monosomy X mosaic with triple X chromosome complement | 3% | 3% | 4% |

| 45,X/46,XY | monosomy X mosaic with normal male sex chromosome complement | 10% | - | - |

Aortic root enlargement increases the risk of aortic dissection in TS although it is unclear whether such a life-threatening disease is always preceded by progressive dilatation as occurs in marfan syndrome (MS). However, despite connective disorders in which guidelines for monitoring of aortic root dimension and indications for surgical intervention are well established[8,9], reliable guidelines are lacking for TS and it is uncertain whether any cut-off value of aortic diameter can be used to identify Turner patients at high-risk of aortic dissection .

Furthermore, since body size is a major determinant of normal aortic dimensions, it may not be appropriate to apply standards derived from adult men to a syndrome more common in women and in which small body size is a main characteristic feature.

Aortic size index (ASI), which adjusts the aortic diameter to the body surface area[4], has been recently introduced as a reliable criterion to predict risk of aortic dissection in TS patients, but its usefulness in this clinical entity is still matter of debate.

We report a case of contained rupture of a dissected aortic arch in a patient with TS who, from the ASI thresholds proposed[9,10], was deemed to be at low risk of aortic dissection and was not eligible for prophylactic surgery.

A 23-year-old woman with TS (45,X karyotype), Graves-Basedow disease and systemic arterial hypertension treated with β-blockers, presented to our hospital facility because of fever unresponsive to antibiotics. She had experienced chest pain 1 mo previously which regressed spontaneously. She had no pain at hospital admission. Blood pressure was 110/82 mmHg.

The patient`s height and weight were 160 cm and 82 kg, respectively, with a body surface area of 1.85 m2. TS was diagnosed at the age of 14 years after an evaluation for short stature and delay of pubertal development. Since then, the patient underwent yearly computed tomography (CT) which showed any aortic dilatation (the diameter of the ascending aorta at the latest scan before admission was 26 mm).

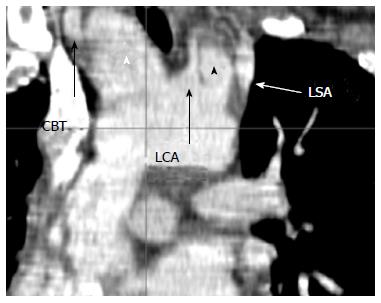

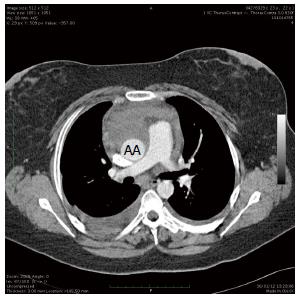

A CT scan at admission revealed a contained rupture of a dissected aortic arch with two false aneurysms between the common brachial trunk (CBT) and the left carotid artery (LCA), and between the LCA and left subclavian artery (LSA) (Figure 1). A peri-aortic hematoma (Figure 2) originating from the arch was present around the anterior aspect of the ascending aorta. The diameters of the aorta were =as follows: ascending aorta 26 mm, arch 30 mm and proximal descending aorta 19 mm. The ascending aortic size index was 14 mm/m2. Echocardiography confirmed the diagnosis and revealed the presence of a bicuspid aortic valve and slight valve insufficiency.

A cardio-circulatory arrest with deep hypothermia was planned. After cannulation of the femoral vessels and the axillary artery trough a 10-mm graft (Vascutek, Terumo Ltd, Egham, United Kingdom) surgical access was gained through median sternotomy. The ascending aorta was resected and the arch inspected: a rupture was detected between the CBT and the LCA with the tear extending towards the LSA. Because of the hematoma, the CBT could not be encircled or clamped and antegrade cerebral perfusion was conducted via the LCA, until the CBT was reconstructed, after which selective antegrade cerebral perfusion via the axillary artery was added. Two 12-mm grafts (Gelsoft, Terumo Ltd, Egham, United Kingdom) were anastomosed to the LCA and LSA and a 14-mm graft (Gelsoft, Terumo Ltd, Egham, United Kingdom) was anastomosed to the CBT. A 28-mm graft (Gelweave Terumo Ltd, Egham United Kingdom) was anastomosed to the distal arch. Afterwards, the prosthesis was clamped and the distal body perfusion resumed through the femoral artery. The aortic valve was a “true” bicuspid valve with no raphe and 180° commissural orientation. The aortic root was normal and the effective height of the aortic valve was 9 mm. Therefore, there was no indication for valve and root replacement. After the proximal anastomosis was completed, the supra-aortic vessels were reimplanted on the ascending aorta prosthesis. Cardiopulmonary bypass time was 440 min, aortic cross-clamp time was 180 min and circulatory body arrest time was 20 min. The operation was routinely completed. After an uneventful course, the patient was transferred to the referring hospital on postoperative day 8. Pathologic examination of the aorta revealed very limited myxoid degeneration with no evidence of either fragmentation or separation of the elastic fibers.

In TS, it remains unclear whether aortic dissection is preceded by progressive dilatation as it is in connective disorders, and whether the thresholds employed in MS can be safely employed for TS. Nevertheless, a large proportion of these patients are small women and, for this reason, it is not correct to use standards derived from adult men in the general population and, for instance, an ascending aortic diameter even < 5 cm may represent, in these patients, a significant dilatation.

To overcome the body size issue, the ASI has been introduced which adjusts the aortic diameter to body surface area[10]. Davies et al[7] showed that patients with thoracic aortic aneurysms with ASI < 27.5 mm/m2 are at low risk (approximately 4% per year), those with ASI between 27.5 and 42.4 mm/m2 are at moderate risk (approximately 8% per year), and those above 42.5 mm/m2 are at high risk (approximately 20% per year) of rupture, dissection, and death. Matura et al[8] employed this index in patients with TS demonstrating that subjects with ASI > 20 mm/m2 require close cardiovascular surveillance and those with ASI ≥ 25 mm/m2 are at highest risk of aortic dissection.

We presented a case of a 23-year-old TS female with contained rupture of a dissected aortic arch. The ASI in our patient was 14 mm/m2 at the level of the ascending aorta. Therefore, following current indications, there was no indication either for surgery or for close surveillance in this patient since the ASI was well below accepted thresholds. Hence, although recent studies[5] have confirmed that body surface area normalization is the most appropriate approach for determining aortic dilation in TS, in our experience ASI was unable to predict impending aortic dissection and rupture.

A recent study employing mathematical models of aortic disease in TS[11], showed that growth of the thoracic aorta is dynamic over time and risk factors such as aortic coarctation, bicuspid aortic valves, age, diastolic blood pressure, body surface area and antihypertensive treatment preferentially accelerated growth of the ascending aorta. Unfortunately, this model was not linked to aortic dissection and rupture. However other papers[3-5] report that bicuspid aortic valve, karyotype 45X, age 20-45 years, and hypertension are factors that confer an increased risk of dissection. All these features were present in the case reported therefore, in our opinion, when one or more of these factors are present, the risk of dissection should be taken into account even with ASI < 20 mm/m2, and a close surveillance by a multidisciplinary team (cardiologists, radiologists, cardiac surgeons) should be recommended.

Although a CT scan with contrast is the most widely used diagnostic procedure, recent studies[12,13] have demonstrated that cardiac magnetic resonance imaging (CMRI) is an important tool for clinical care and it improves risk stratification of TS patients. Indeed, CMRI is outstanding for detection of the degree of aortic dilatation and coarctation that are not visible on echocardiography[14], but is limited by its high cost and poor tolerability due to claustrophobia and anxiety in some TS patients. Meanwhile, fast scan seeds, low radiation dose and increased anatomic coverage are improving the image quality of cardiac multidetector CT (MDCT) and reducing patient risks in children. Cardiac MDCT is also considered to effectively bridge the gaps among echocardiography and cardiac MRI in children with congenital heart disease. In addition, cardiac MDCT has better cost benefit compared with CMRI.

In conclusion, our experience emphasizes the need for careful monitoring and surgical evaluation of TS patients even when the ASI is small if other significant risk factors are present. Even though this is only a case report, it provides the idea and sounds the alarm that using only an ASI is not sufficient for risk stratification for aortic dissection in patients with TS.

Large prospective studies are needed for risk stratification for aortic dissection in TS in order to identify reliable thresholds to identify patients who may require referral for surgery before life-threatening complications occur.

We gratefully thank Dr. Judith Wilson for the English revision of the paper.

A 23-year-old woman with Turner syndrome (TS).

Fever unresponsive to antibiotics, and chest pain.

Other causes of chest pain, thoracic back pain.

Blood, metabolic panel and liver function tests were within normal limits.

A computed tomography-scan at admission revealed a contained rupture of a dissected aortic arch with two false aneurysms between the common brachial trunk and the left carotid artery and the left carotid artery and the left subclavian artery, respectively. The diameters of the aorta were as follows: ascending aorta 26 mm, arch 30 mm and proximal descending aorta 19 mm.The ascending aortic size index was 14 mm/m2.

Pathologic examination of the aorta revealed very limited myxoid degeneration with no evidence of either fragmentation or separation of the elastic fibers.

The patient underwent aortic arch replacement and common brachial trunk, left carotid artery, and left subclavian artery replacement.

Aortic root enlargement increases the risk of dissection in Turner syndrome but it is unclear whether aortic dissection is always preceded by progressive dilatation as occurs in Marfan syndrome. Nevertheless, a large proportion of these patients are small women and, for this reason, it is not correct to use standards derived from adult men in the general population and, for instance, an ascending aortic diameter even < 5 cm may represent, in these patients, a significant dilatation.

Aortic size index, which adjusts the aortic diameter to the body surface area, has been recently introduced as a reliable criterion to predict risk for aortic dissection in TS patients but its usefulness in this clinical entity is still a matter of debate.

This case report emphasizes the need for careful monitoring and surgical evaluation of the patients even when the aortic size index is < 20 mm/m2 if other significant risk factors are present.

This is a potentially interesting case study that describes the limitation in using aortic size index to assess risk of aortic dissection in patients with Turner’s syndrome.

P- Reviewers: Durante W, O-Uchi J, Winkel BG S- Editor: Wen LL L- Editor: Cant MR E- Editor: Wu HL

| 1. | Saenger P, Wikland KA, Conway GS, Davenport M, Gravholt CH, Hintz R, Hovatta O, Hultcrantz M, Landin-Wilhelmsen K, Lin A. Recommendations for the diagnosis and management of Turner syndrome. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2001;86:3061-3069. [PubMed] |

| 2. | El-Mansoury M, Barrenäs ML, Bryman I, Hanson C, Larsson C, Wilhelmsen L, Landin-Wilhelmsen K. Chromosomal mosaicism mitigates stigmata and cardiovascular risk factors in Turner syndrome. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf). 2007;66:744-751. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 79] [Cited by in RCA: 88] [Article Influence: 4.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Gravholt CH, Juul S, Naeraa RW, Hansen J. Prenatal and postnatal prevalence of Turner’s syndrome: a registry study. BMJ. 1996;312:16-21. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 118] [Cited by in RCA: 114] [Article Influence: 3.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Hook EB, Warburton D. The distribution of chromosomal genotypes associated with Turner’s syndrome: livebirth prevalence rates and evidence for diminished fetal mortality and severity in genotypes associated with structural X abnormalities or mosaicism. Hum Genet. 1983;64:24-27. [PubMed] |

| 5. | Bondy CA. Aortic dissection in Turner syndrome. Curr Opin Cardiol. 2008;23:519-526. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 128] [Cited by in RCA: 105] [Article Influence: 6.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Gutmark-Little I, Hor KN, Cnota J, Gottliebson WM, Backeljauw PF. Partial anomalous pulmonary venous return is common in Turner syndrome. J Pediatr Endocrinol Metab. 2012;25:435-440. [PubMed] |

| 7. | Davies RR, Gallo A, Coady MA, Tellides G, Botta DM, Burke B, Coe MP, Kopf GS, Elefteriades JA. Novel measurement of relative aortic size predicts rupture of thoracic aortic aneurysms. Ann Thorac Surg. 2006;81:169-177. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 389] [Cited by in RCA: 379] [Article Influence: 19.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Matura LA, Ho VB, Rosing DR, Bondy CA. Aortic dilatation and dissection in Turner syndrome. Circulation. 2007;116:1663-1670. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 258] [Cited by in RCA: 234] [Article Influence: 13.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Braverman AC. Timing of aortic surgery in the Marfan syndrome. Curr Opin Cardiol. 2004;19:549-550. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Maureira JP, Vanhuyse F, Lekehal M, Hubert T, Vigouroux C, Mattei MF, Grandmougin D, Villemot JP. Failure of Marfan anatomic criteria to predict risk of aortic dissection in Turner syndrome: necessity of specific adjusted risk thresholds. Interact Cardiovasc Thorac Surg. 2012;14:610-614. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Mortensen KH, Erlandsen M, Andersen NH, Gravholt CH. Prediction of aortic dilation in Turner syndrome - enhancing the use of serial cardiovascular magnetic resonance. J Cardiovasc Magn Reson. 2013;15:47. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 39] [Cited by in RCA: 45] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Gutmark-Little I, Backeljauw PF. Cardiac magnetic resonance imaging in Turner syndrome. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf). 2013;78:646-658. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Kim HK, Gottliebson W, Hor K, Backeljauw P, Gutmark-Little I, Salisbury SR, Racadio JM, Helton-Skally K, Fleck R. Cardiovascular anomalies in Turner syndrome: spectrum, prevalence, and cardiac MRI findings in a pediatric and young adult population. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2011;196:454-460. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 81] [Cited by in RCA: 87] [Article Influence: 6.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Dawson-Falk KL, Wright AM, Bakker B, Pitlick PT, Wilson DM, Rosenfeld RG. Cardiovascular evaluation in Turner syndrome: utility of MR imaging. Australas Radiol. 1992;36:204-209. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 77] [Cited by in RCA: 83] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |