Published online Apr 26, 2014. doi: 10.4330/wjc.v6.i4.213

Revised: December 6, 2013

Accepted: February 18, 2014

Published online: April 26, 2014

Processing time: 188 Days and 0.7 Hours

Cardioembolic events are one of the most feared complications in patients with non-valvular atrial fibrillation (NVAF) and a formal contraindication to oral anticoagulation (OAC). The present case report describes a case of massive peripheral embolism after an implantable cardiac defibrillator (ICD) shock in a patient with NVAF and a formal contraindication to OAC due to previous intracranial hemorrhage. In order to reduce the risk of future cardioembolic events, the patient underwent percutaneous left atrial appendage (LAA) occlusion. A 25 mm Amplatzer™ Amulet was implanted and the patient was discharged the following day without complications. The potential risk of thrombus dislodgement after an electrical shock in patients with NVAF and no anticoagulation constitutes a particular scenario that might be associated with an additional cardioembolic risk. Although LAA occlusion is a relatively new technique, its usage is rapidly expanding worldwide and constitutes a very valid alternative for patients with NVAF and a formal contraindication to OAC.

Core tip: The present case report discusses the treatment of a patient with atrial fibrillation and contraindication to anticoagulation who presented with a massive peripheral embolism after an implantable cardiac defibrillator shock. The manuscript describes the successful management of the patient and discusses a clinical setting that might be associated with an increased cardioembolic risk.

- Citation: Freixa X, Andrea R, Martín-Yuste V, Fernández-Rodríguez D, Brugaletta S, Masotti M, Sabaté M. Cardiac embolism after implantable cardiac defibrillator shock in non-anticoagulated atrial fibrillation: The role of left atrial appendage occlusion. World J Cardiol 2014; 6(4): 213-215

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1949-8462/full/v6/i4/213.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4330/wjc.v6.i4.213

Cardioembolic events are one of the most feared complications in patients with non-valvular atrial fibrillation (NVAF) and a formal contraindication to oral anticoagulation (OAC). In these patients, the risk of stroke can generally be predicted using the CHA2DS2VASc score[1]. However, factors not contemplated in the CHA2DS2VASc score may also play a relevant role. One of these factors might be the presence of implantable cardiac defibrillators (ICD) and the potential risk of thrombus dislodgement after electrical shocks. In the following report, we describe a case of massive peripheral embolism after an ICD shock in a patient with NVAF and a formal contraindication to OAC. In order to reduce the risk of new cardioembolic events, the patient underwent percutaneous left atrial appendage (LAA) occlusion. Although LAA occlusion is a relatively new technique, its usage is rapidly expanding worldwide and constitutes a valid alternative for patients with NVAF and a formal contraindication to OAC.

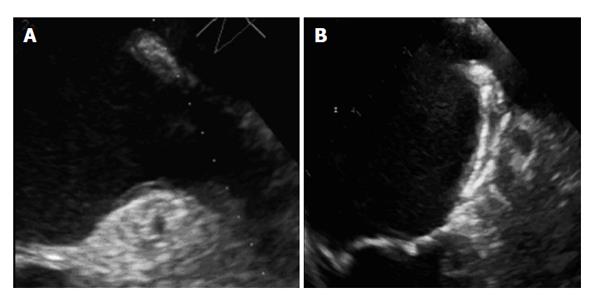

This was a 61-year-old male with a previous history of hypertension, diabetes, stroke, dilated cardiomyopathy and ICD for secondary prevention. The patient also presented chronic NVAF with a CHA2DS2VASc of 5 treated initially with OAC. Anticoagulation was, however, discontinued after an episode of intracranial hemorrhage and single aspirin treatment was started. Six months after OAC discontinuation, the patient was admitted with a massive abdominal embolism after an appropriate ICD shock requiring mechanical aspiration of emboli in the right hepatic and superior mesenteric arteries. After consultation with the neurology department, reintroduction of OAC was not recommended as a result of the risk of recurrent intracranial bleeding. Transesophageal echocardiography (TEE) showed no thrombus in the LAA and a mean diameter of 22 mm at the landing area. Considering the high risk of thrombus formation as a result of the slow LAA blood flow velocity (0.3 m/s) and the risk of cardioembolic recurrence after another potential ICD shock, percutaneous LAA occlusion with a 25 mm Amplatzer™ Amulet™ was conducted without complications (Figure 1). The patient was discharged the following day under dual antiplatelet therapy. At 3 mo, TEE showed complete LAA sealing and the patient was left on single antiplatelet therapy again.

In patients with NVAF, cardioembolic strokes are generally more disabling and more lethal than strokes from other sources[2]. Although OAC has been shown to be highly effective in reducing the rate of cardioembolic events and deaths[3], between 30% and 50%[4] of patients present a formal contraindication for OAC, have unstable international normalized ratios or are not fully compliant. Currently, percutaneous LAA occlusion represents a valid alternative in patients with NVAF and a formal contraindication for OAC, but it might also be considered for those at high risk of bleeding or drug cessation (II-b indication)[5]. Although the presence of an ICD is not contemplated in the CHA2DS2VASc score, the authors believe that it should be taken into consideration when assessing the cardioembolic risk in patients with NVAF and no anticoagulation. In fact, the incidence of cardioembolic events after electrical shocks remains high in these patients, ranging between 5% and 7% with every shock[6]. In addition, the CHA2DS2VASc score in patients with ICDs is generally high as a result of the increased cardiovascular comorbidity. The usual high CHA2DS2VASc score of this population, the unpredictable formation of thrombus in the LAA without anticoagulation, and the increased risk of thrombus dislodgement after ICD shocks constitute a particular scenario that might be associated with a high risk of cardioembolic events. In this sense, the occlusion of the LAA, an anatomical structure related with most cardioembolic events, might be a valid alternative. Although further evidence will be necessary to determine if the presence of ICD constitutes an independent predictor of cardioembolic events in patients with NVAF and the absence of OAC, the present case report is hypothesis generating as it highlights the specific risk of these patients and describes a potential alternative for their management.

Secondary prevention for cardiac embolism in a patient with previous peripheral embolism and non-anticoagulated atrial fibrillation.

Non-anticoagulated atrial fibrillation in a patient with previous implantable cardiac defibrillator and cardiac embolism after electrical shock.

The potential risk of thrombus dislodgement after an electrical shock in patients with atrial fibrillation and no anticoagulation constitutes a particular scenario that might be associated with an additional cardioembolic risk.

Previous intracranial hemorrhage.

Non-valvular atrial fibrillation (NVAF) with formal contraindication to anticoagulation due to previous intracranial bleeding.

Percutaneous left atrial appendage (LAA) occlusion.

Although LAA occlusion is a relatively new technique, its usage is rapidly expanding worldwide and constitutes a valid alternative for patients with atrial fibrillation and a formal contraindication to oral anticoagulation (OAC).

The authors reported a case with non-valvular atrial fibrillation and a formal contraindication to OAC, who had undergone percutaneous LAA occlusion after the occurrence of massive abdominal embolism. This case report is interesting and suggestive but there are several questions to be solved.

P- Reviewers: Nakos G, Teragawa H S- Editor: Ma YJ L- Editor: Roemmele A E- Editor: Liu SQ

| 1. | Camm AJ, Kirchhof P, Lip GY, Schotten U, Savelieva I, Ernst S, Van Gelder IC, Al-Attar N, Hindricks G, Prendergast B. Guidelines for the management of atrial fibrillation: the Task Force for the Management of Atrial Fibrillation of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Eur Heart J. 2010;31:2369-2429. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3227] [Cited by in RCA: 3335] [Article Influence: 222.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Lin HJ, Wolf PA, Kelly-Hayes M, Beiser AS, Kase CS, Benjamin EJ, D’Agostino RB. Stroke severity in atrial fibrillation. The Framingham Study. Stroke. 1996;27:1760-1764. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 839] [Cited by in RCA: 918] [Article Influence: 31.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Hart RG, Pearce LA, Aguilar MI. Meta-analysis: antithrombotic therapy to prevent stroke in patients who have nonvalvular atrial fibrillation. Ann Intern Med. 2007;146:857-867. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3260] [Cited by in RCA: 3426] [Article Influence: 190.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Bungard TJ, Ghali WA, Teo KK, McAlister FA, Tsuyuki RT. Why do patients with atrial fibrillation not receive warfarin? Arch Intern Med. 2000;160:41-46. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 397] [Cited by in RCA: 412] [Article Influence: 16.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Camm AJ, Lip GY, De Caterina R, Savelieva I, Atar D, Hohnloser SH, Hindricks G, Kirchhof P. 2012 focused update of the ESC Guidelines for the management of atrial fibrillation: an update of the 2010 ESC Guidelines for the management of atrial fibrillation. Developed with the special contribution of the European Heart Rhythm Association. Eur Heart J. 2012;33:2719-2747. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2342] [Cited by in RCA: 2416] [Article Influence: 185.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Bjerkelund CJ, Orning OM. The efficacy of anticoagulant therapy in preventing embolism related to D.C. electrical conversion of atrial fibrillation. Am J Cardiol. 1969;23:208-216. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 325] [Cited by in RCA: 290] [Article Influence: 5.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |