Published online Mar 26, 2014. doi: 10.4330/wjc.v6.i3.112

Revised: December 11, 2013

Accepted: January 17, 2014

Published online: March 26, 2014

Processing time: 141 Days and 5.8 Hours

Giant coronary artery aneurysms and coronary artery fistulae are uncommon pathologies. We present the case of an elderly woman who was referred to cardiology for investigation of possible ischaemic heart disease prior to orthopaedic surgery. The patient had developed chest pain in the setting of a septic total knee replacement associated with changes on electrocardiography. Coronary angiography revealed multiple coronary arteriovenous fistulae associated with giant coronary artery aneurysm causing steal syndrome in the setting of haemodynamic stress.

Core tip: This case report presents the angiographic findings of a rare occurrence of multiple coronary arteriovenous fistulae associated with giant coronary artery aneurysm and steal syndrome in the setting of haemodynamic stress.

- Citation: Castles AV, Mogilevski T, Haq MAU. Steal syndrome secondary to coronary artery fistulae associated with giant aneurysm. World J Cardiol 2014; 6(3): 112-114

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1949-8462/full/v6/i3/112.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4330/wjc.v6.i3.112

This case report presents the angiographic findings of a rare occurrence of multiple coronary arteriovenous (AV) fistulae associated with giant coronary artery aneurysms and steal syndrome in the settings of haemodynamic stress.

A 76-year-old lady was referred to cardiology for investigation of ischaemic heart disease (IHD) prior to orthopaedic surgery.

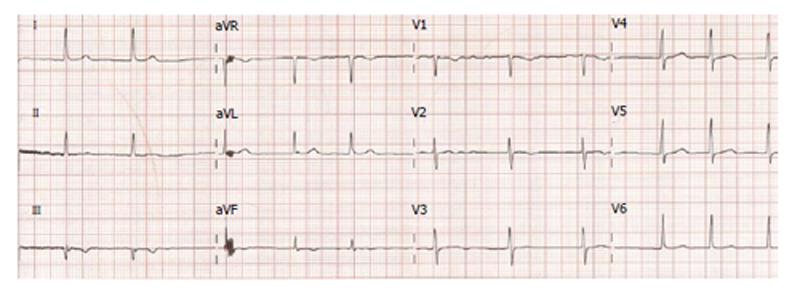

The patient was undergoing staged revision of a septic total knee replacement. After the first revision surgery, she experienced ischaemic chest pain. She had a history of chronic rate-controlled atrial fibrillation but no history of IHD. Her cardiovascular risk factors include hypertension, type 2 diabetes mellitus, age and post-menopausal status. There was no associated troponin rise however the electrocardiography revealed anterior T-wave inversion (Figure 1). Transthoracic echocardiography demonstrated mild tricuspid regurgitation, mild pulmonary hypertension, normal left ventricular function, and mild to moderately dilated right ventricle.

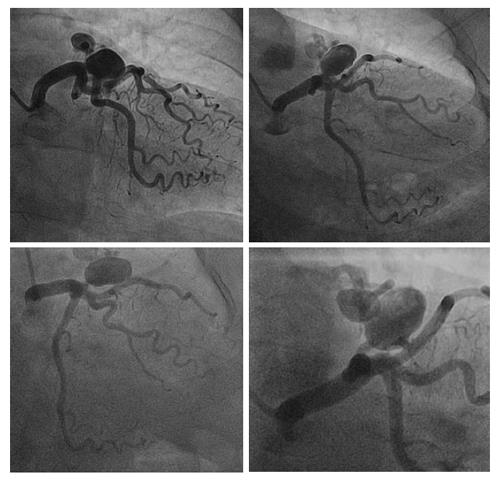

A coronary angiogram was performed via transradial approach. The study revealed two fistulae arising from distal left main coronary artery and proximal left anterior descending artery supplying a large aneurysm (Figure 2). The aneurysm, measuring 2.4 cm × 1.6 cm, drained into the pulmonary artery (PA) through multiple AV fistulae. The remainder of the coronary vasculature did not reveal any significant pathology.

In this case, the coronary artery aneurysm with associated fistulae was not deemed amenable to transcatheter closure/coiling given the size and multiple openings. Surgical repair was considered appropriate because of the risks of aneurysm rupture, endocarditis, thrombosis/embolism or heart failure[1,2]. However the risk of significant periprocedural myocardial ischaemia secondary to upcoming orthopaedic procedure was small relative to the risk of undergoing cardiac surgery particularly in the context of underlying sepsis. The definitive management was therefore delayed until the patient’s full recovery from sepsis and surgery.

Coronary artery aneurysms are fairly uncommon, being found in less than five percent of patients undergoing coronary angiography, most commonly in the right coronary artery[3,4]. Males are more commonly affected than females[4]. The most common cause of coronary artery aneurysm in adults is atherosclerosis. As such, the same risk factors that predispose patients to atherosclerotic disease are also risk factors for coronary artery aneurysm formation[3,4]. Other disease processes that damage the coronary arteries can also predispose to aneurysm formation; these include arteritis (infectious or inflammatory), syphilis, connective tissue diseases, Kawasaki’s disease and metastatic malignancy. In addition, traumatic insult to the vessels, as in trauma, coronary angiography/intervention and aortic dissection, are implicated. Congenital malformations also increase the risk of developing coronary artery aneurysm[3].

Coronary artery fistulae are rare, with an observed prevalence of less than one percent of patients on coronary angiography[3-7]. Again, the right coronary artery is more commonly affected than the left coronary vessels[5,7]. The fistulae drain into the right cardiac chambers more commonly than the left, with the most common drainage sites being the right ventricle, right atrium or PA, and less frequently the coronary sinus, left atrium, left ventricle or superior vena cava[5,7].

Coronary artery fistulae may be either congenital or acquired[1,5-8]. Congenital fistulae may occur as an isolated anomaly or in conjunction with other congenital heart anomalies/malformations[7]. Causes of acquired coronary fistulae include disease processes that damage the vessels, such as infection, inflammation and malignancy[7,8]. In addition, trauma to the vessels, whether iatrogenic (as in cardiothoracic surgery and interventional procedures) or non-iatrogenic, may lead to fistula formation[6-8].

Coronary artery aneurysm with associated fistula (CAAAF), being a combination of two uncommon pathologies, is extremely rare. As of 2005, only 50 cases had been reported[1,4]. Little information is available about the aetiology of CAAAF but it has been observed that “most of the aneurysms were observed at the termination site of the fistulae”[4].

Risks associated with CAAAF include aneurysm rupture, endocarditis, thrombosis/embolism, myocardial ischaemia and heart failure[1,2]. Transcatheter, surgical or conservative management may be considered depending on the size, location and clinical context for the individual patient[1,2].

An elderly lady with chest pain in the setting of sepsis.

Ischaemic heart disease was the most likely clinical diagnosis given the description of chest pain and the risk factor profile.

Musculoskeletal or gastroesophageal reflux disease as exacerbation of chest pain with exertion could not be assessed given the patient’s mobility was significantly limited by her orthopaedic condition.

Serial troponin levels were negative.

Coronary angiography demonstrated multiple arteriovenous (AV) left main and left anterior descending coronary artery fistulae associated with giant aneurysm.

The patient was medically managed for her hypertension, diabetes mellitus, atrial fibrillation and ischaemic chest pain.

Coronary angiogram images and electrocardiography are provided in the case report.

Coronary artery aneurysm refers to an abnormal dilatation of a coronary artery segment, relative to adjacent segments or other coronary arteries. Coronary artery (vascular) fistula refers to an abnormal connection between a coronary artery and another vessel or cardiac chamber.

Coronary artery fistulae may only become symptomatic in the context of haemodynamic stress.

The authors present a rare case report of multiple coronary AV fistulae with giant coronary artery aneurysms and steal syndrome. The manuscript is clearly written and well organized.

P- Reviewers: Shee JJ, Ueda H, Ye YC S- Editor: Song XX L- Editor: A E- Editor: Liu SQ

| 1. | Hirose H, Amano A, Yoshida S, Nagao T, Sunami H, Takahashi A, Nagano N. Coronary artery aneurysm associated with fistula in adults: collective review and a case report. Ann Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1999;5:258-264. [PubMed] |

| 2. | Jamil G, Khan A, Malik A, Qureshi A. Aneurysmal coronary cameral fistula. BMJ Case Rep. 2013;pii: bcr2013008649. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Burgaft MB. [Peripheral iridectomy in the treatment of closed-angle glaucoma]. Oftalmol Zh. 1987;436-438. [PubMed] |

| 4. | Papadopoulos DP, Ekonomou CK, Margos P, Moyssakis I, Anagnostopoulou S, Benos I, Votteas V. Coronary artery aneurysms and coronary artery fistula as a cause of angina pectoris. Clin Anat. 2005;18:77-78. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Nakamura M, Matsuoka H, Kawakami H, Komatsu J, Itou T, Higashino H, Kido T, Mochizuki T. Giant congenital coronary artery fistula to left brachial vein clearly detected by multidetector computed tomography. Circ J. 2006;70:796-799. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Doganay S, Bozkurt M, Kantarci M, Erkut B. Coronary artery-pulmonary vein fistula diagnosed by multidetector computed tomography. J Cardiovasc Med (Hagerstown). 2009;10:428-430. [PubMed] |

| 7. | Mangukia CV. Coronary artery fistula. Ann Thorac Surg. 2012;93:2084-2092. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 141] [Cited by in RCA: 169] [Article Influence: 13.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Tachibana M, Mukouhara N, Hirami R, Fujio H, Yumoto A, Watanuki Y, Hayashi A, Suminoe I, Koudani H. Double congenital fistulae with aneurysm diagnosed by combining imaging modalities. Acta Med Okayama. 2013;67:305-309. [PubMed] |