Published online Mar 26, 2014. doi: 10.4330/wjc.v6.i3.107

Revised: January 7, 2014

Accepted: January 15, 2014

Published online: March 26, 2014

Processing time: 160 Days and 12.9 Hours

AIM: To assess current practice of United Kingdom cardiologists with respect to patients with reported shellfish/iodine allergy, and in particular the use of iodinated contrast for elective coronary angiography. Moreover we have reviewed the current evidence-base and guidelines available in this area.

METHODS: A questionnaire survey was send to 500 senior United Kingdom cardiologists (almost 50% cardiologists registered with British Cardiovascular Society) using email and first 100 responses used to analyze practise. We involved cardiologists performing coronary angiograms routinely both at secondary and tertiary centres. Three specific questions relating to allergy were asked: (1) History of shellfish/iodine allergy in pre-angiography assessment; (2) Treatments offered for shellfish/iodine allergy individuals; and (3) Any specific treatment protocol for shellfish/iodine allergy cases. We aimed to establish routine practice in United Kingdom for patients undergoing elective coronary angiography. We also performed comprehensive PubMed search for the available evidence of relationship between shellfish/iodine allergy and contrast media.

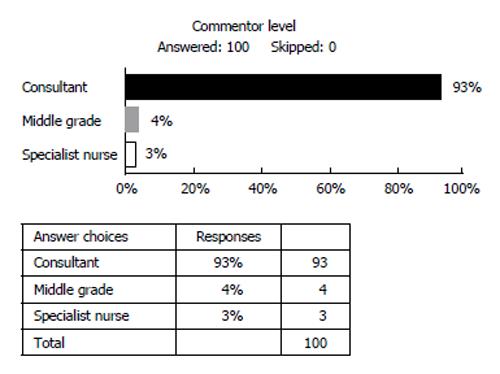

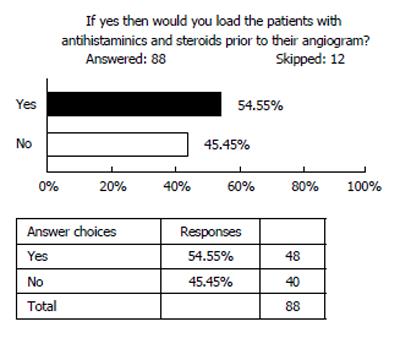

RESULTS: A total of 100 responses were received, representing 20% of all United Kingdom cardiologists. Ninety-three replies were received from consultant cardiologists, 4 from non-consultant grades and 3 from cardiology specialist nurses. Amongst the respondents, 66% routinely asked about a previous history of shellfish/iodine allergy. Fifty-six percent would pre-treat these patients with steroids and anti-histamines. The other 44% do nothing, or do nonspecific testing based on their personal experience as following: (1) Skin test with 1 mL of subcutaneous contrast before intravenous contrast; (2) Test dose 2 mL contrast before coronary injection; (3) Close observation for shellfish allergy patients; and (4) Minimal evidence that the steroid and anti-histamine regime is effective but it makes us feel better.

CONCLUSION: There is no evidence that allergy to shellfish alters the risk of reaction to intravenous contrast more than any other allergy and asking about such allergies in pre-angiogram assessment will not provide any additional information except propagating the myth.

Core tip: This short survey explains how easily evidence base is missed out from real life practice. There has never been any evidence to relate shellfish/iodine to contrast media, yet the myth been propagated for decades. Our survey gives a reminder and eye opener to change the practice to evidence base and thus helps in the patient care avoiding unnecessary medications.

- Citation: Baig M, Farag A, Sajid J, Potluri R, Irwin RB, Khalid HMI. Shellfish allergy and relation to iodinated contrast media: United Kingdom survey. World J Cardiol 2014; 6(3): 107-111

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1949-8462/full/v6/i3/107.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4330/wjc.v6.i3.107

There is a widely held view that a link exists between patient-reported shellfish allergy and increased risk of allergic reaction to iodinated contrast agents. Such agents are widely employed across many medical disciplines, including cardiology. Both invasive and non-invasive (in the case of computed tomography coronary angiography) diagnostic investigations require the use of such agents. Currently, guidance of percutaneous coronary angiography and many structural cardiac interventions mandates the use of iodinated contrast.

Historically the link between shellfish allergy and radio-contrast dates back to the early 1970s. Papers by Witten et al[1] and Shehadi[2] reported adverse reaction to radio-contrast in patients with history of seafood allergy. It is commonly believed that the individual with reported shellfish allergy is at higher risk of iodinated contrast allergy. It is often further assumed that this is due to the presence of iodine in both situations. Despite little evidence to support this relationship, many physicians still believe that shellfish/iodine allergy increases risk, and this may alter how such patients are treated. Various different methods of managing this perceived increased risk are currently employed, including prophylactic administration of corticosteroids or antihistamine preparations, and even avoidance of iodinated contrast altogether.

Our aims were to assess the current practice of United Kingdom cardiologists with respect to patients with reported shellfish/iodine allergy, and in particular the use of iodinated contrast for elective coronary angiography. Moreover we have reviewed the current evidence-base and guidelines available in this area.

A questionnaire survey was sent by email to United Kingdom cardiologists. Both secondary and tertiary centres were targeted, as were multiple cardiologists within individual trusts. The aim was to establish routine practice amongst the surveyed cardiologists or specialist nurses for patients undergoing elective invasive coronary angiography. With this in mind, the three main questions posed were: (1) Do you ask about shellfish/iodine allergy history during pre-angiography assessment? (2) If patients have history of shellfish/iodine allergy would you give pre-treatment? and (3) If pre-treatment is offered what is the protocol?

The physicians or specialist nurses completing the questionnaire were encouraged to elaborate and provide additional comments, as they felt necessary.

A comprehensive literature search was performed using PubMed. The following terms were used Shellfish Allergy, Iodinated contrast, and contrast allergy.

The questionnaire was sent to 500 cardiologists across the United Kingdom. A total of 100 responses were received, representing 20% of all United Kingdom cardiologists. Ninety-three replies (Figure 1) were received from consultant cardiologists, 4 from non-consultant grades and 3 from cardiology specialist nurses.

Amongst the respondents, 66% (Figure 2) routinely ask about a previous history of shellfish/iodine allergy while 56% would pre-treat these patients with steroids and anti-histamines (Figure 3). The other 44% do nothing, or do nonspecific testing based on their personal experience.

We found great deal of variation in practice with the following protocols followed: (1) Skin test with 1 ml of subcutaneous contrast before intravenous contrast; (2) Test dose 2 mL contrast before coronary injection; (3) Close observation for shellfish allergy patients; and (4) Minimal evidence that the steroid and anti-histamine regime is effective but it makes us feel better.

Shellfish allergy is one of the commonest food allergies in adults, and is a common cause of food-induced anaphylaxis[3]. Seafood consumption has increased in popularity and frequency worldwide so as the adverse reactions[3].

Shellfish can be classified into molluscs and arthropoda (crustaceans). Arthropods include crab, crayfish, lobster, prawn and shrimp. Molluscs is subclassified into gastropod (abalone, conch, limpet, snail and whelk), bivalves (clam, cockle, mussel, oyster and scallop) and cephalopods (cuttlefish, octopus and squid). Four groups of allergens have been identified in shellfish: Tropomyosin, arginine kinase, myosin light chain and sarcoplasmic calcium-binding protein. Among the allergens identified, tropomyosin, a contractile protein, is considered a major allergen for prawn, and other crustaceans, such as shrimp, crayfish, lobster, crab and barnacles[4].

The overall prevalence of shellfish allergy in the western world (United States, Canada and Europe) is approximately 0.6%, ranging between 0% to 10%[5]. Of the shellfish, prawns are most frequently implicated (62% of shellfish allergy), followed by crab, lobster and then the molluscan species[6]. Symptoms of shellfish allergy can range from mild urticaria to life threatening anaphylaxis. Most reactions are Immunoglobulin E (IgE)-mediated with rapid onset and may be gastrointestinal, cutaneous, or respiratory. Symptoms may be limited to transient oral itching or burning sensation within minutes of eating shellfish. Management of allergy is the same as for any other allergies i.e., antihistamines, corticosteroids and adrenaline in severe or life-threatening reactions.

Shellfish allergy is mainly due to tropomyosins and iodine has in fact no role to play in allergic reactions. Moreover, iodine is an integral part of human body and essential for survival, therefore iodine itself cannot be considered an allergen. Radio-contrast media is composed of anions (iodide) and cations (sodium or meglumine). Iodine molecule is an effective X-ray absorber in the energy range therefore iodinated contrast media allow enhanced visibility of vascular structures and organs during radiographic procedures. There are two basic types of contrast media: ionic high osmolality contrast media (HOCM) and non-ionic low osmolality contrast media (LOCM), and both contains iodine molecule. HOCM (ionic) creates more charged particles and have more osmolality whereas LOCM (non-ionic) generates less dissociation and therefore have low osmolality. Examples of currently used ionic and non-ionic contrast media are: Perflutren-protein type-A microspheres injection (optison), iohexol injection (omnipaque), and non-ionic iodixanol injection (Visipaque).

Reactions to intravenous contrast are not truly allergic[7] and not mediated via IgE. Instead there is direct stimulation of mast cells and basophils to release mediators leading to “anaphylactoid” reactions (pseudo-allergy). This may lead to urticaria, bronchospasm, hypotension, and even cardiac arrest. Previous allergic reactions to shellfish would create IgE sensitized to those allergens, but this sensitized IgE would play no role in allergic reactions to contrast media as they are not IgE mediated. Moreover, the cause of “anaphylactoid” reactions to contrast media is not the iodine in the contrast but is thought to be its hyper-osmolality compared to blood[8].

Hyperosmolar contrast regardless of its composition is an irritant and will cause vasodilatation, increased vascular permeability, and direct cardiotoxicity and nephrotoxicity. Non-ionic contrast (LOCM) still uses iodine as a radiopacification agent, but fewer iodinated molecules are created with different side chains that reduce dissociation in solution. Fewer molecules in solution decrease the osmolarity and therefore cause fewer side effects and reactions. These compounds are usually about one-half to one-third as osmotically active as the ionic forms[9] and associated with fourfold or greater reduction in all adverse reaction and fivefold decrease in severe adverse reactions[9]. The risk of reactions to intravenous contrast media ranges from 0.2%-17%, depending on the type of contrast used, the severity of reaction considered, and the prior history of any allergy[9].

High risk patients include patients with previous intravenous contrast reactions, asthma, multiple true allergies, those taking beta-blockers or metformin, females, elderly and diseases that increase the risk of adverse reactions e.g., pheochromocytoma, hyperthyroidism, thyroid cancer, renal failure[10,11]. Atopy, in general, confers an increased risk of reaction to contrast administration, but the risk of contrast reaction is low, even in patients with a history of “iodine allergy”, seafood allergy, or prior contrast reaction. Allergies to shellfish, in particular, do not increase the risk of reaction to intravenous contrast any more that of other allergies. A history of prior reaction to contrast increases the risk of mild reactions to as high as 7%-17%, but has not been shown to increase the rate of severe reactions[9].

Mild reactions including warmth, nausea and vomiting occur only for short duration and do not require any treatment. Moderate reactions (e.g., vomiting, sweating and swellings) occur in 1% of patients and frequently require treatment. Severe reactions occur in 0.02%-0.5% and deaths in 0.0006%-0.006%; neither has been related to “iodine allergy”, seafood allergy, or prior contrast reaction[9]. The most severe reactions, including death, have been reported to occur at similar rates with both types of contrast Media[12].

Pre testing for contrast allergy is challenging and has been proposed in patients with a history of an anaphylactic reactions[13]. Skin testing and Radioallergosorbent test have not been helpful in the diagnosis of contrast allergy as only a fraction of patients with severe reactions have a positive skin test[14]. Small test doses are also not useful not only because severe reactions can occur even with small doses but also because of severe reactions to large doses of contrast media observed in patients who have tolerated small doses well. Therefore, no valid single test available to diagnose contrast allergy except only when symptoms occur after the contrast injection. However one can identify patients who are at high risk of contrast allergy[15] and be prepared for adverse reactions.

Despite the increased use of non-ionic LOCM, and a decrease in the incidence of mild to moderate, and possibly severe reactions, pre-medications are still widely used in clinical practice. On the basis of observational data, Greenberger et al[16] concluded in 1991 that patients with a previous reaction to high osmolality iodinated contrast media should receive oral prednisone and diphenhydramine with or without adrenaline. Since then, professional organisations have recommended a variety of regimens and combinations of methyl-prednisolone with or without an antihistamine[17], oral prednisolone or methyl-prednisolone[18], or intravenous hydrocortisone and intramuscular diphenhydramine[19].

Steroid pre-medications reduce the incidence of respiratory symptoms due to contrast media from 1.4% to 0.4%, and the incidence of combined respiratory and hemodynamic symptoms from 0.9% to 0.2%[20]. Thus, to prevent one episode of a potentially life threatening, iodinated contrast medium related reaction, about 100 to 150 patients need to receive steroids prophylactically[20]. Disastrous anaphylactic complications after administration of iodinated contrast media seem to be rare. In the analysed trials, more than 10000 patients received an iodinated contrast medium but no reports of death, cardiopulmonary resuscitation, irreversible neurological deficit, or prolonged hospital stay was reported[20].

Although it has been noted that steroid pre-medication decreases the total number of adverse events, it does not reduce the number of severe events. No significant effect is seen when steroids are given within 3 h before administration of intravenous contrast media[7]. Even with longer protocols, steroid premedication has not shown a statistically significant improvement in severe adverse reaction rates[9].

For antihistamines, limited evidence shows that they may prevent some reactions. One may conclude that valid data supporting the efficacy of drug combinations or the use of premedication in patients with a history of allergic reactions are completely lacking[20]. Severe allergic reactions due to contrast media seem to be rare; this may explain why no reports of disastrous reactions exist.

The treatment of an acute reaction to contrast media is no different from any other anaphylactic reaction. Treatment may include injectable epinephrine and antihistamines, as well as the use of intravenous fluids for low blood pressure and shock[20].

In a conclusions, There is widespread variation in the management of patients who report previous shellfish allergy by United Kingdom cardiologists.

There is no evidence that allergy to shellfish alters the risk of reaction to intravenous contrast more than any other allergy, and this is due to: (1) Shellfish allergy is not related to iodine; instead the vast majority are due to tropomyosin; (2) Shellfish allergy is IgE mediated, whilst intravenous contrast allergy is due to direct stimulation of mast cells and basophils. Hence previous exposure to shellfish allergens and subsequently sensitized IgE, would play no role; and (3) Contrast pseudo allergic reactions are due to hyper-osmolality of contrast (free iodine molecule) rather than the bound iodine molecule.

It may be concluded therefore that there is no additional information gained by inquiring about previous shellfish/iodine allergy during pre-angiogram assessment. There is no specific relevance to this particular allergy, and such questioning potentially propagates the myth. If patients ask question about shellfish/iodine allergy they should be reassured and explained that there is no relation to contrast allergy.

There is no compelling evidence that anti-histamines have a role in prevention of allergic events, although corticosteroid pre-medication has shown benefit in reducing minor reactions, but no significant benefit in decreasing severe and fatal reactions.

It would be appropriate to use low osmolarity, non-ionic contrast for patients with atopy, patients with previous reaction to intravenous contrast, and patients with systemic disease that increase their risk for contrast reaction. Almost all the life threatening reactions to intravenous contrast occur immediately or within 20 min of contrast injection so all patients with previous allergic reactions should be monitored and treat severe reactions the same way you would treat any severe anaphylactic reaction.

Radio-contrast is commonly used in both invasive and non-invasive diagnostic investigations but relation of the contrast media to shellfish and iodine allergy is poorly understood.

The authors conducted a questionnaire-based survey in United Kingdom to find out practice in relation to Shellfish/iodine allergy. They also looked at the current literature available and evidence base to establish the relationship between contrast media and shellfish/iodine allergy, if there was any.

The authors’ survey found the more than 50% of the Cardiologists ask about shellfish/iodine allergy and pre-treat patients undergoing coronary angiography assuming that there exists a relation between the two. Looking at the evidence there is no such relation and by asking such questions in pre-angiography sessions they are propagating the myth.

The authors’ research suggests no pre-treatment required for patient with history of shellfish/iodine allergy undergoing coronary angiography. This also prevents un-necessary medication use and stay in the hospital.

LOCM: Low osmolality contrast media, HOCM: High osmolality contrast media, IgE: Immunoglobulin E.

The present study showed at first the current practice of United Kingdom cardiologists with respect to patients with reported shellfish/iodine allergy, and in the use of contrast agent for elective coronary angiography. Second, the differences between shellfish and contrast allergy were explained in details including those mechanisms. Finally, the author stated the meaning of the pre-medication using antihistamines and/or steroids for the prevention of the contrast induced allergy. The suggestions in this manuscript seems to be very interesting, instructive and valuable, and the information in which may be of great use for many physicians in the real clinical setting.

P- Reviewers: Bagur R, Peteiro J, Taguchi I S- Editor: Wen LL L- Editor: A E- Editor: Liu SQ

| 1. | Witten DM, Hirsch FD, Hartman GW. Acute reactions to urographic contrast medium: incidence, clinical characteristics and relationship to history of hypersensitivity states. Am J Roentgenol Radium Ther Nucl Med. 1973;119:832-840. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 140] [Cited by in RCA: 143] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Shehadi WH. Adverse reactions to intravascularly administered contrast media. A comprehensive study based on a prospective survey. Am J Roentgenol Radium Ther Nucl Med. 1975;124:145-152. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 234] [Cited by in RCA: 188] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Woo CK, Bahna SL. Not all shellfish “allergy” is allergy! Clin Transl Allergy. 2011;1:3. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 42] [Cited by in RCA: 46] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Lee AJ, Gerez I, Shek LP, Lee BW. Shellfish allergy--an Asia-Pacific perspective. Asian Pac J Allergy Immunol. 2012;30:3-10. [PubMed] |

| 5. | Rona RJ, Keil T, Summers C, Gislason D, Zuidmeer L, Sodergren E, Sigurdardottir ST, Lindner T, Goldhahn K, Dahlstrom J. The prevalence of food allergy: a meta-analysis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2007;120:638-646. [PubMed] |

| 6. | Sicherer SH, Muñoz-Furlong A, Sampson HA. Prevalence of seafood allergy in the United States determined by a random telephone survey. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2004;114:159-165. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 384] [Cited by in RCA: 349] [Article Influence: 16.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | American College of Radiology. Manual on contrast media. Re-ston, VA: American College of Radiology, 2008. Accessed September 20 2009; Available from: http: //www.acr.org/contrast-manual.. |

| 8. | Sicherer SH. Risk of severe allergic reactions from the use of potassium iodide for radiation emergencies. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2004;114:1395-1397. [PubMed] |

| 9. | Schabelman E, Witting M. The relationship of radiocontrast, iodine, and seafood allergies: a medical myth exposed. J Emerg Med. 2010;39:701-707. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 73] [Cited by in RCA: 69] [Article Influence: 4.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Canter LM. Anaphylactoid reactions to radiocontrast media. Allergy Asthma Proc. 2005;26:199-203. [PubMed] |

| 11. | Keller DM. Iodinated contrast media raises risk for thyroid dysfunction. Arch Intern Med. 2012;172:153-159. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Boehm I. Seafood allergy and radiocontrast media: are physicians propagating a myth? Am J Med. 2008;121:e19. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Dewachter P, Trechot P, Mouton-Faivre C. Anaphylactoid reactions to contrast media: literature review (article in French). Cah d’Anesthésiol. 2003;51:341-354. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 14. | Laroche D, Aimone-Gastin I, Dubois F, Huet H, Gérard P, Vergnaud MC, Mouton-Faivre C, Guéant JL, Laxenaire MC, Bricard H. Mechanisms of severe, immediate reactions to iodinated contrast material. Radiology. 1998;209:183-190. [PubMed] |

| 15. | Barrett BJ, Parfrey PS. Clinical practice. Preventing nephropathy induced by contrast medium. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:379-386. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 433] [Cited by in RCA: 388] [Article Influence: 20.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Greenberger PA, Patterson R. The prevention of immediate generalized reactions to radiocontrast media in high-risk patients. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1991;87:867-872. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 212] [Cited by in RCA: 165] [Article Influence: 4.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | American College of Radiology. Patient selection and preparation strategies. In: Manual on contrast media 2006; Available from: http: //www.acr.org/s_acr/sec.asp?CID = 2131&DID = 16687. |

| 18. | Morcos SK, Thomsen HS, Webb JA. Prevention of generalized reactions to contrast media: a consensus report and guidelines. Eur Radiol. 2001;11:1720-1728. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 117] [Cited by in RCA: 94] [Article Influence: 4.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Joint Task Force on Practice Parameters; American Academy of Allergy, Asthma and Immunology; American College of Allergy, Asthma and Immunology; Joint Council of Allergy, Asthma and Immunology. The diagnosis and management of anaphylaxis: an updated practice parameter. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2005;115:S483-S523. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 319] [Cited by in RCA: 278] [Article Influence: 13.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Tramèr MR, von Elm E, Loubeyre P, Hauser C. Pharmacological prevention of serious anaphylactic reactions due to iodinated contrast media: systematic review. BMJ. 2006;333:675. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 146] [Cited by in RCA: 119] [Article Influence: 6.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |