Published online Sep 26, 2013. doi: 10.4330/wjc.v5.i9.364

Revised: July 26, 2013

Accepted: August 8, 2013

Published online: September 26, 2013

Processing time: 168 Days and 1.7 Hours

Cardiac involvement as an initial presentation of malignant lymphoma is a rare occurrence. We describe the case of a 26 year old man who had initially been diagnosed with myocardial infiltration on an echocardiogram, presenting with a testicular mass and unilateral peripheral facial paralysis. On admission, electrocardiograms (ECG) revealed negative T-waves in all leads and ST-segment elevation in the inferior leads. On two-dimensional echocardiography, there was infiltration of the pericardium with mild effusion, infiltrative thickening of the aortic walls, both atria and the interatrial septum and a mildly depressed systolic function of both ventricles. An axillary biopsy was performed and reported as a T-cell lymphoblastic lymphoma (T-LBL). Following the diagnosis and staging, chemotherapy was started. Twenty-two days after finishing the first cycle of chemotherapy, the ECG showed regression of T-wave changes in all leads and normalization of the ST-segment elevation in the inferior leads. A follow-up Two-dimensional echocardiography confirmed regression of the myocardial infiltration. This case report illustrates a lymphoma presenting with testicular mass, unilateral peripheral facial paralysis and myocardial involvement, and demonstrates that regression of infiltration can be achieved by intensive chemotherapy treatment. To our knowledge, there are no reported cases of T-LBL presenting as a testicular mass and unilateral peripheral facial paralysis, with complete regression of myocardial involvement.

Core tip: In this report, we describe the case of a 26 year old man who was admitted with infiltration of the pericardium, aortic walls, both atria and the interatrial septum. An axillary biopsy was performed and reported as a T-cell lymphoblastic lymphoma (T-LBL). Following the diagnosis and staging, chemotherapy was started. Twenty-two days after finishing the first cycle of chemotherapy, a follow-up two-dimensional echo confirmed regression of the myocardial infiltration. We describe an unusual case of precursor T-LBL presenting with cardiac involvement and demonstrate that regression of myocardial infiltration can be achieved by intensive chemotherapy treatment.

- Citation: Vinicki JP, Cianciulli TF, Farace GA, Saccheri MC, Lax JA, Kazelian LR, Wachs A. Complete regression of myocardial involvement associated with lymphoma following chemotherapy. World J Cardiol 2013; 5(9): 364-368

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1949-8462/full/v5/i9/364.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4330/wjc.v5.i9.364

Gross tumor formation in any of the cardiac chambers is rare, particularly at the time of presentation and in cases of lymphoma[1-4]. Symptoms are usually very subtle and non-specific, particularly in the setting of co-existing morbidities. We report an unusual case of a 26 year old man presenting with a gross intracardiac mass, testicular mass and unilateral peripheral facial paralysis, who was ultimately diagnosed with T-cell lymphoblastic lymphoma (T-LBL).

The patient is a 26-year-old man, presenting with a testicular tumor and peripheral facial paralysis noted 21 d before admission. Physical exam revealed a left peripheral facial paralysis and ipsilateral conjunctival congestion, bilateral supraclavicular and inguinal lymph nodes, left axillary nodes and a left testicular tumor measuring 7 cm × 5 cm, as well as signs consistent with bilateral (predominantly right sided) pleural effusion. On electrocardiograms (ECG), there was sinus tachycardia, ST-segment elevation in leads II, III and aVF and negative T waves in all leads except aVR. Laboratory values were remarkable for anemia (hematocrit 36%), leukocytosis (13000/mL), thrombocytosis (615000/mL) and lactate dehydrogenase of 1787 UI/L.

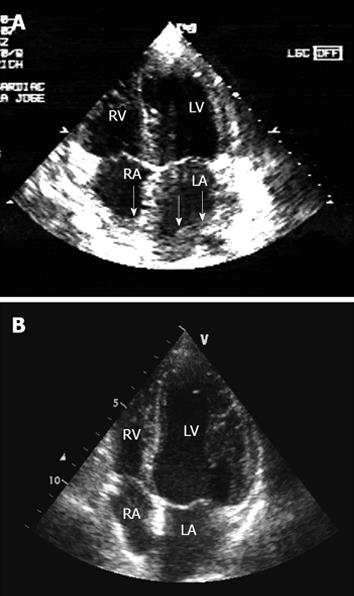

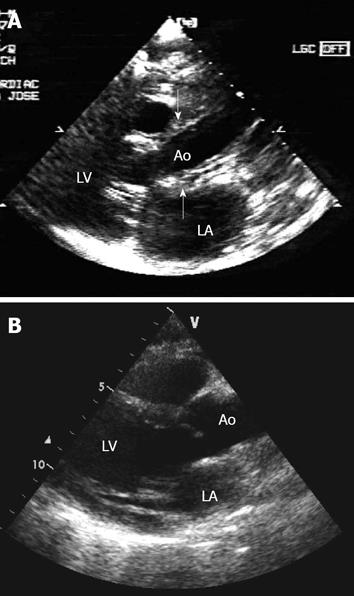

The computed tomography (CT) showed an orbit with diffuse thickening of the inferior, medial and lateral rectus muscles, a right maxillary sinus filled with a polypoid structure and soft tissue density, a cluster of lymph nodes in the mediastinum causing a mass effect in the adjacent vessels, pericardial thickening and another lymph node cluster in the abdomen involving areas of the aorta and its branches (celiac axis, left iliac artery and left renal artery). On 2-dimensional echocardiography (2D-echo) (Figures 1A and 2A), there was pericardial infiltration with very mild effusion, infiltrative thickening of the aortic walls, left atrium, right atrium, interatrial septum and the tricuspid annulus, and mildly depressed systolic function of both ventricles. The axillary biopsy revealed findings consistent with T-LBL.

Following diagnosis and staging, chemotherapy was started, according to the HyperCVAD regimen (hyperfractionated cyclophosphamide, vincristine, adriamycin and dexamethasone). Treatment consisted of IV cyclophosphamide and mesna during the first three days, combined with high dose dexamethasone 4 times a week during the first 15 d. Additionally, methotrexate, citarabine and dexamethasone were injected into the intrathecal space once a week during the first two weeks. Doxorubicin and vincristine were administered the day after discontinuing cyclophosphamide and on day 11 a new dose of the second agent was added.

Twenty-two days after finishing the first course of chemotherapy, the ECG showed significant regression of the negative T waves in all leads and of the ST segment elevation in the inferior leads. Follow-up 2D echo confirmed total regression of the cardiac and aortic infiltrate (Figures 1B and 2B).

The patient required multiple admissions due to progression of his baseline disease; dissemination was found in the bone marrow, nerve roots, meninges, cranial nerves and bone, with partial response to chemotherapy. Other regimens were tried and despite maximum support measures the patient died after the fourth hospital admission.

In our patient, cardiac involvement was not the main pathological process and the systemic component was quite evident. Hence, the case is consistent with a diffuse cardiac infiltration by lymphoma.

In the literature, the majority of patients reported present with various and non-specific symptoms, such as dyspnea, edema, arrhythmia, cardiac tamponade (metastatic tumors of the heart have also been associated with pericardial effusion, particularly hemorrhagic effusion), palpitations and congestive heart failure, and are related to the location and volume of the tumor as well as the functional status of the heart[1,5-8]. In one large study, the incidence of signs and symptoms plus electrocardiographic abnormalities in patients who died with malignant lymphoma was similar in those with cardiac metastases when compared to those without cardiac metastases[9]. Scott et al[10] stated that the most important sign of cardiac invasion in a patient with malignant disease is the onset of congestive heart failure without another apparent cause. The presence of cardiac arrhythmias under similar conditions is also suggestive.

Based upon the data of 22 large autopsy series, Reynen et al[11] established that the frequency of primary cardiac tumors is approximately 0.02%, corresponding to 200 tumors in 1 million autopsies[8]. Most of these primary cardiac tumors are intracavitary and preferentially develop in the left atrium, thereby leading to left ventricular inflow obstruction. Embolism is also common[8]. Primary cardiac lymphoma, defined as a lymphoma involving only the heart and pericardium, is extremely rare, with a reported incidence ranging from 0.15% to 1%[1,5]. Secondary cardiac infiltration from nodal lymphoma of the mediastinum appears to be more common with approximately 35%-40% of patients dying with malignant lymphomas reported to have myocardial involvement. The majority of reported cases were diagnosed at autopsy because of the rapid progression and non-specific clinical symptoms[1-4]. In our case, this entity was prospectively diagnosed in vivo by two-dimensional echocardiography. We have found only 4 reports previous to the present case (Table 1)[12-17] of metastatic cardiac lymphoma[13-16].

| Ref. | Age/sex | Symptoms | Type of lymphoma | Localization in heart | Diagnostic tools | Therapy and evolution |

| Wiernik et al[12] | 42/M | Ureteral obstruction Acute myocardial infarction Heart failure | Lymphocytic lymphoma | Gross infiltration of the lateral wall of the left ventricle | Autopsy | Chemotherapy Radiotherapy Died 9 yr later |

| Lestuzzi et al[13] | 23/F | None | Lymphoblastic lymphoma | Cardiac apex | 2D-echo | Local radiotherapy Died 12 mo later |

| 53/F | Dyspnea | Burkitt’s lymphoma | Epicardium, posterior ventricular wall and interventricular septum | 2D-echo | Local radiotherapy Died 20 d later | |

| Lynch et al[14] | NA | NA | NA | Pericardial and myocardial | NA | Chemotherapy |

| Cracowski et al[15] | 25/M | Dyspnea | High grade malignant lymphoma | Left ventricular hypertrophy with increased echogenicity of the myocardial walls and marked decrease in left ventricular ejection fraction | 2D-echo, EMB | Chemotherapy |

| Cho et al[16] | 39/F | Dyspnea and palpitation | Diffuse large cell type non-Hodgkin's lymphoma | Interventricular septum and left ventricular posterior wall | 2D-echo | Chemotherapy |

| Bergler-Klein et al[17] | 34/F | None | Burkitt’s lymphoma | Asymmetric hypertrophy of the mid and distal septum with a speckled appearance of the myocardium and LV apical region | 2D-echo MRI, PET | Chemotherapy Died 9 mo later |

| Vinicki et al | 26/M | Testicular mass and unilateral peripheral facial paralysis | T-cell lymphoblastic lymphoma | Pericardial, aorta, both atrial and the interatrial septum | 2D-echo | Chemotherapy Died 4 mo later |

Roberts et al[9] carried out a necropsy study of 196 patients with malignant lymphoma and found cardiac disease in 48 cases. Among all lymphoma subtypes, cardiac infiltration was seen in 16% of patients with Hodgkin’s lymphoma, 25% of patients with non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma, and 33% of patients with mycosis fungoides. Of these 48 patients, lymphoma was identified grossly in the heart in 27 cases and found on microscopical examination alone in 21. The pericardium and epicardial fat, particularly in the atrioventricular sulci, were most commonly affected. Nodular deposits within the cardiac chambers were also found[8,18,19]. According to a study of 25 autopsy cases, T-cell lymphomas, compared with B-cell lymphomas, invade the heart more frequently and aggressively and are associated with a variety of cardiac manifestations[4].

Most cases of cardiac lymphoma are solid, infiltrative nodular tumors affecting 1 or several cardiac chambers[13-17]. The right heart is the most common site of cardiac lymphoma. Lymphomatous infiltration of the pericardium is also seen in a number of cases. In contrast, cardiac valve involvement with hematogenous malignancies is uncommon and has been rarely reported to occur as a result of the direct extension of malignant lymphoma from extravascular lesions[2]. In our patient, the initial description of the first 2D-echo in the clinical case showed severe thickening and infiltration of the myocardium and its subsequent regression after chemotherapy.

The method of choice to detect cardiac metastases and their complications is 2D-echo. It is a simple, safe and non-invasive method and can provide better anatomic details than other more invasive studies[8,11,18,20].

The infiltrating masses have a peculiar, granular echocardiographic texture which is always different to normal myocardium. The ventricular walls appear thickened and hypokinetic or even akinetic in the area of infiltration. The transmural invasion modifies the epicardial and endocardial contours. All these aspects allow the differential diagnosis with thrombi or other masses, which can be adherent to the endocardium[17].

Although cardiac metastases may rarely be the first presenting sign of an underlying malignancy, the presence of malignant disease elsewhere is an important clue to the etiology of an intracavitary infiltration[11].

In 1992, Lestuzzi et al[21] studied the usefulness of transesophageal echocardiography (TEE) performed on 70 patients for the evaluation of paracardiac neoplastic masses (26 patients had non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma, 23 had Hodgkin’s lymphoma and the rest corresponded to isolated cases of mediastinal tumors). Twenty-three patients underwent repeat TEE after medical or radiation therapy treatments: a total of 101 TEE examinations were performed. The TEE allowed better visualization of the mass, cardiac chambers and great vessels than transthoracic echocardiography in 68 of 101 examinations. Most of the patients underwent CT within 2 wk of TEE. The TEE and CT data were comparable in 58 cases. In 14 of 58 cases, the anatomic data (site, size of the mass, cardiovascular infiltration) obtained by TEE fully corresponded to those obtained by CT. In 3 cases, TEE clearly demonstrated an intracardiac extension of the mass not detected by CT. In 30 cases in which CT was not diagnostic, TEE allowed diagnosis of or exclusion of the infiltration of cardiovascular structures. In 34 patients, TEE contributed additional hemodynamic data not obtained by any other imaging technique. As a conclusion, they consider that CT scan is less precise in defining highly mobile structures, does not provide real-time images, structures are shown on a smaller scale and transthoracic echocardiography is limited mostly to neoplasms of the anterior mediastinum. In contrast, TEE allows a better visualization of the mediastinum (albeit with “blind areas” due to the airway) which allows making the differential diagnosis between vascular and nonvascular lesions, assessing the superior vena cava and pulmonary vein flow, the infiltration of the descending thoracic aorta and the pulmonary artery and its branches[21].

Compared to ultrasound, computed tomography and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) provide tissue differentiation between solid, liquid, hemorrhagic and fatty lesions and myocardial metastases can be better delineated. The most compelling indication for MRI is pre-operative assessment of patients with known cardiac masses. According to Lund et al[22], it helps to determine the need to operate and aided in surgical planning[8,22,23].

Cardiac treatment is mostly confined to palliative measures. Surgical resection is only indicated in exceptional cases of solitary intracavitary heart metastases, leading to obliteration of cardiac chambers or valve obstruction if the tumor of origin was surgically resected in toto and the patient appears to have a good prognosis[8,20,24,25]. Frequently, however, complete resection fails and postoperative mortality is high[2,8]. Usually, cardiac infiltrates in leukemia and lymphoma respond well to radio- or chemotherapy[1,7,8].

Here, we describe an unusual case of precursor T-LBL presenting with a testicular mass, unilateral peripheral facial paralysis and cardiac involvement, and demonstrate that regression of myocardial infiltration can be achieved by intensive chemotherapy treatment. The definitive diagnosis should have been made by myocardial biopsy, which was certainly not indicated in our patient given his severe systemic involvement.

Although the progression of the disease could be suppressed during chemotherapy, it relapsed early after completing the treatment cycles. Interestingly, although the relapse occurred at several sites different from the initial site of presentation, it did not involve the myocardium.

Secondary neoplastic myocardial infiltration, although frequent at autopsy, is rarely recognized in vivo. In our case, this entity was prospectively diagnosed in vivo by 2D-echo echocardiography. In addition, it allowed recognition of myocardial infiltration and definition of the location and size of metastases and it helped to decide the most appropriate therapy and to assess the results. Identification and treatment of all secondary neoplastic localizations, however, is important and of clinical relevance, mainly for tumors entailing a less guarded prognosis.

P- Reviewer Hardt S S- Editor Zhai HH L- Editor Roemmele A E- Editor Wang CH

| 1. | Lee PW, Woo KS, Chow LT, Ng HK, Chan WW, Yu CM, Lo AW. Images in cardiovascular medicine. Diffuse infiltration of lymphoma of the myocardium mimicking clinical hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Circulation. 2006;113:e662-e664. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Furihata M, Ido E, Iwata J, Sonobe H, Ohtsuki Y, Takata J, Chikamori T, Doi Y. Adult T cell leukemia/lymphoma with massive involvement of cardiac muscle and valves. Pathol Int. 1998;48:221-224. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Daisley H, Charles W. Cardiac involvement with lymphoma/leukemia: a report of three autopsy cases. Leukemia. 1997;11 Suppl 3:522-524. [PubMed] |

| 4. | Chinen K, Izumo T. Cardiac involvement by malignant lymphoma: a clinicopathologic study of 25 autopsy cases based on the WHO classification. Ann Hematol. 2005;84:498-505. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 41] [Cited by in RCA: 47] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Ikeda H, Nakamura S, Nishimaki H, Masuda K, Takeo T, Kasai K, Ohashi T, Sakamoto N, Wakida Y, Itoh G. Primary lymphoma of the heart: case report and literature review. Pathol Int. 2004;54:187-195. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 77] [Cited by in RCA: 84] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | McDonnell PJ, Mann RB, Bulkley BH. Involvement of the heart by malignant lymphoma: a clinicopathologic study. Cancer. 1982;49:944-951. [PubMed] |

| 8. | Reynen K, Köckeritz U, Strasser RH. Metastases to the heart. Ann Oncol. 2004;15:375-381. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 231] [Cited by in RCA: 265] [Article Influence: 12.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Roberts WC, Glancy DL, DeVita VT. Heart in malignant lymphoma (Hodgkin’s disease, lymphosarcoma, reticulum cell sarcoma and mycosis fungoides). A study of 196 autopsy cases. Am J Cardiol. 1968;22:85-107. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 220] [Cited by in RCA: 206] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Scott RW, Garvin CF. Tumors of the heart and pericardium. Am Heart J. 1939;17:431-436. |

| 11. | Reynen K. Frequency of primary tumors of the heart. Am J Cardiol. 1996;77:107. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 500] [Cited by in RCA: 533] [Article Influence: 18.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Wiernik PH. Spontaneous regression of hematologic cancers. Natl Cancer Inst Monogr. 1976;44:35-38. [PubMed] |

| 13. | Lestuzzi C, Biasi S, Nicolosi GL, Lodeville D, Pavan D, Collazzo R, Guindani A, Zanuttini D. Secondary neoplastic infiltration of the myocardium diagnosed by two-dimensional echocardiography in seven cases with anatomic confirmation. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1987;9:439-445. [PubMed] |

| 14. | Lynch M, Cobbs W, Miller RL, Martin RP. Massive cardiac involvement by malignant lymphoma. Cardiology. 1996;87:566-568. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Cracowski JL, Trémel F, Nicolini F, Bost F, Mallion JM. Myocardial localization of malignant non-Hodgkin lymphoma responsive to chemotherapy. Arch Mal Coeur Vaiss. 1997;90:1527-1531. [PubMed] |

| 16. | Cho JG, Ahn YK, Cho SH, Lee JJ, Chung IJ, Park MR, Kim HJ, Jeong MH, Park JC, Kang JC. A case of secondary myocardial lymphoma presenting with ventricular tachycardia. J Korean Med Sci. 2002;17:549-551. [PubMed] |

| 17. | Bergler-Klein J, Knoebl P, Kos T, Streubel B, Becherer A, Schwarzinger I, Maurer G, Binder T. Myocardial involvement in a patient with Burkitt’s lymphoma mimicking hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2003;16:1326-1330. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Allen DC, Alderdice JM, Morton P, Mollan PA, Morris TC. Pathology of the heart and conduction system in lymphoma and leukaemia. J Clin Pathol. 1987;40:746-750. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Bogren HG, DeMaria AN, Mason DT. Imaging procedures in the detection of cardiac tumors, with emphasis on echocardiography: a review. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol. 1980;3:107-125. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | DePace NL, Soulen RL, Kotler MN, Mintz GS. Two dimensional echocardiographic detection of intraatrial masses. Am J Cardiol. 1981;48:954-960. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 121] [Cited by in RCA: 101] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Lestuzzi C, Nicolosi GL, Mimo R, Pavan D, Zanuttini D. Usefulness of transesophageal echocardiography in evaluation of paracardiac neoplastic masses. Am J Cardiol. 1992;70:247-251. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Lund JT, Ehman RL, Julsrud PR, Sinak LJ, Tajik AJ. Cardiac masses: assessment by MR imaging. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1989;152:469-473. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 111] [Cited by in RCA: 81] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Go RT, O’Donnell JK, Underwood DA, Feiglin DH, Salcedo EE, Pantoja M, MacIntyre WJ, Meaney TF. Comparison of gated cardiac MRI and 2D echocardiography of intracardiac neoplasms. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1985;145:21-25. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 54] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Yoshikawa J, Sabah I, Yanagihara K, Owaki T, Kato H, Tanemoto K. Cross-sectional echocardiographic diagnosis of large left atrial tumor and extracardiac tumor compressing the left atrium. Limitation of M mode echocardiography in distinguishing the two lesions. Am J Cardiol. 1978;42:853-857. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Come PC, Riley MF, Markis JE, Malagold M. Limitations of echocardiographic techniques in evaluation of left atrial masses. Am J Cardiol. 1981;48:947-953. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 72] [Cited by in RCA: 64] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |